86

Ulcers

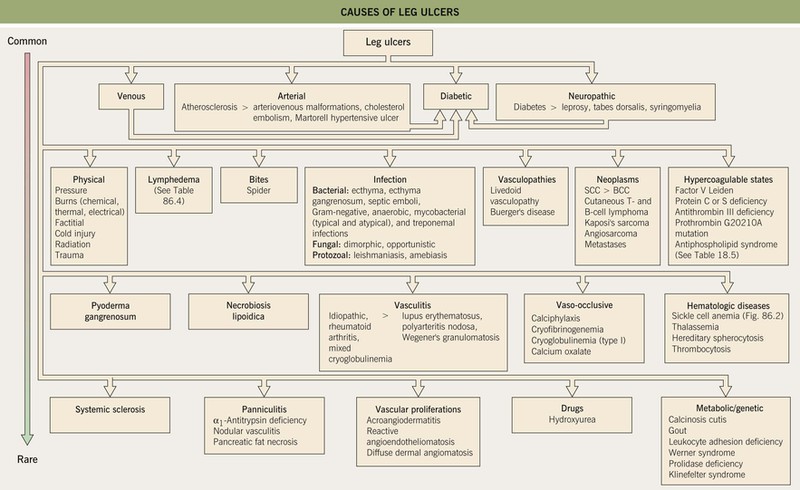

• The most common types of leg ulcers – venous, arterial, and neuropathic – as well as pressure ulcers, lymphedema, and an approach to wound healing are reviewed (see below); additional physical, inflammatory, infectious, metabolic, and neoplastic causes of leg ulcers are outlined in Fig. 86.1.

Fig. 86.1 Causes of leg ulcers. Patients with Behçet’s disease can also develop leg ulcers due to vasculitis and/or venous insufficiency related to deep vein thromboses. Erosive pustular dermatosis is another occasional cause of leg ulcers. Hydroxyurea-induced leg ulcers are exceedingly painful, surrounded by atrophic skin, and often located on the malleolus or tibial crest.

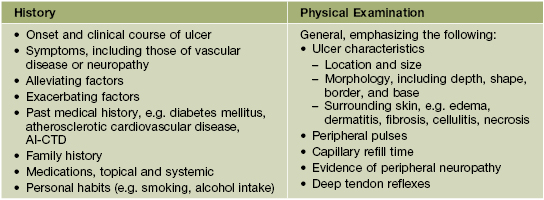

• Features to consider in the history and physical examination of patients with a leg ulcer are presented in Table 86.1, and routine laboratory testing often includes a CBC, ESR, and blood glucose and serum albumin levels; microbial cultures, evaluation for hypercoagulability (see Table 18.5), and additional studies depend on the clinical setting.

Table 86.1

Points to include in the history and physical examination of patients with a leg ulcer.

Adapted from Kanj LF, Phillips TJ. Management of leg ulcers. Fitpatrick’s J. Clin. Dermatol. 1994;Sept/Oct:52–60.

Venous Ulcers

• Venous hypertension and insufficiency represent the most common causes of chronic leg ulcers.

• Prevalence increases with age, and risk factors include female sex, obesity, pregnancy, prolonged standing, and family history of venous insufficiency; hypercoagulability can be a contributing factor, especially in patients with a history of deep vein thrombosis or livedoid vasculopathy (Fig. 86.3; see Chapter 18).

Fig. 86.3 Livedoid vasculopathy. A Multiple hemorrhagic crusts and small, very painful ulcers associated with brown discoloration due to hemosiderin deposits. B Stellate, porcelain-white atrophic scars with peripheral telangiectatic papules, referred to as atrophie blanche. B, Courtesy, Julie V. Schaffer, MD.

• Ulcers tend to have irregular borders and a yellow fibrinous base, with a predilection for the area above the medial malleolus

(Fig. 86.4); the ulcers can become large but are often fairly shallow, with granulation tissue evident upon debridement.

Fig. 86.4 Venous ulcers over the medial malleolus. A Granulation tissue is evident in ~15% of the ulcer bed. Note the surrounding stasis dermatitis with erythema, crusting, and scaling as well as scarring. B Induration due to lipodermatosclerosis, hemosiderin deposition, and atrophie blanche scars are present in the surrounding skin. B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• Surrounding skin has signs of venous hypertension such as yellow-brown discoloration due to hemosiderin deposits, pinpoint petechiae, stasis dermatitis, lipodermatosclerosis, and, occasionally, acroangiodermatitis (Fig. 86.5).

Fig. 86.5 Associated findings in patients with venous hypertension and insufficiency. A Venulectasias of the instep. B Brown discoloration of the foot and ankle due to hemosiderin deposits within dermal macrophages in addition to hyperpigmentation. Note the cutoff at Wallace’s line. C Lipodermatosclerosis with violet-brown discoloration, tenderness, and induration that typically begins above the medial malleolus. D Stasis dermatitis and chronic lipodermatosclerosis with serous crusts and the ‘inverted champagne bottle’ or ‘bowling pin’ configuration. E Acroangiodermatitis (pseudo-Kaposi’s sarcoma). Violaceous plaque in a patient with venous hypertension. Histologically, these lesions can resemble Kaposi’s sarcoma. A, B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD; C, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD. D, Courtesy, Ariela Hafner, MD, and Eli Sprecher, MD.

• Other findings include varicosities and edema > lymphedema of the lower extremities (Fig. 86.6); swelling and aching of the legs is worsened by dependency (e.g. prolonged standing) and improved by leg elevation and the use of compression therapy; other dependent sites, such as a large pannus, can develop similar clinical changes (Fig. 86.7).

Fig. 86.6 Venous abnormalities of the lower extremity. A Venulectasias and a few reticular varicosities at the site of a perforator vein. B Reticular varicosities; note the blue-green color. C Larger saphenous varicosities may also be evident. Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

Fig. 86.7 Lymphedema, lipodermatosclerosis, and chronic ulceration of the dependent portion of the pannus. The changes are similar to those that can be seen on the distal lower extremities.

• DDx: see Fig. 86.1; coexistent arterial insufficiency (see below) or uncompensated congestive heart failure should be excluded before initiating compression therapy.

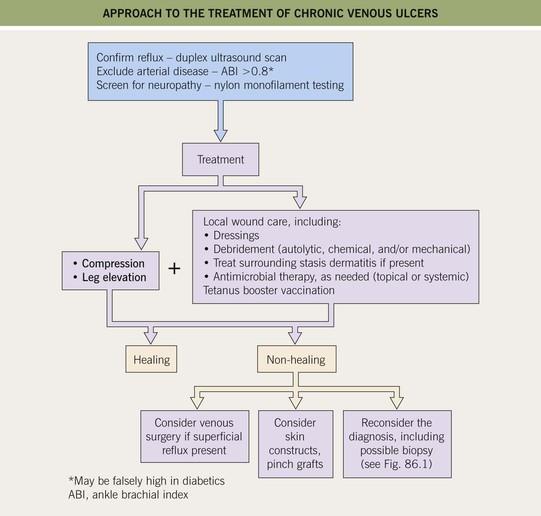

• Evaluation and Rx: an approach to the patient with a chronic venous ulcer is presented in Fig. 86.8.

Arterial Ulcers

• Surrounding skin is typically hairless, shiny, and atrophic (Fig. 86.9).

Fig. 86.9 Arterial ulcer. The punched-out appearance and surrounding smooth shiny skin are common features. Courtesy, Ariela Hafner, MD, and Eli Sprecher, MD.

• DDx: other causes of ulcers in patients with PAD include cholesterol emboli (Fig. 86.10), diffuse dermal angiomatosis (painful violaceous plaques with central ulceration), and Buerger’s disease (thrombangiitis obliterans; inflammatory and vaso-occlusive disorder in smokers affecting upper and lower extremities); patients with co-existing diabetes mellitus may have overlapping features (see below).

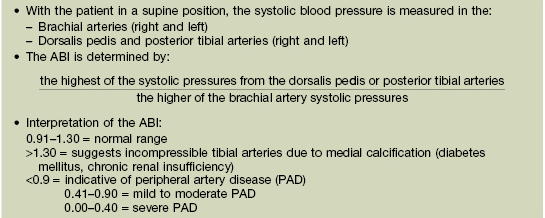

• Evaluation: the ankle–brachial index (ABI) is used to screen for PAD (Table 86.2); additional assessment may include duplex ultrasonography, CT angiography, and magnetic resonance angiography.

Neuropathic (Mal Perforans) and Diabetic Ulcers

• Neuropathic ulcers are typically ‘punched out’ with a hyperkeratotic rim, arising in a background of callused skin; they are usually located on pressure points and over bony prominences (e.g. metatarsal heads, heels, great toes) (Fig. 86.11).

Fig. 86.11 Neuropathic ulcers in patients with diabetes mellitus and peripheral neuropathy. Common locations are the plantar surface of the heel (A) and the great toe (B). Note the thick rim of callus. A, Courtesy, Ariela Hafner, MD, and Eli Sprecher, MD.

• Evaluation: neurologic examination using nylon monofilament to test sensation ± nerve conduction studies/electromyography and determination of the ABI (see Table 86.2); assessment for infection utilizing laboratory studies (e.g. CBC, ESR/C-reactive protein), wound cultures (tissue from biopsy is higher yield than swabs), and imaging to exclude osteomyelitis (e.g. radiographs [low sensitivity], MRI) as indicated by clinical suspicion.

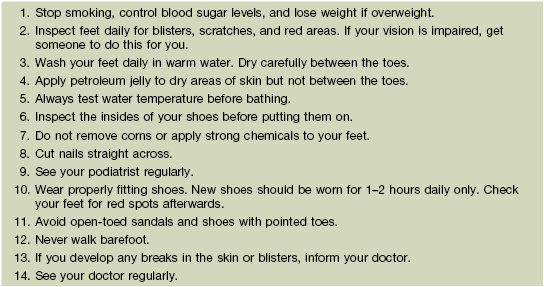

• Rx: wound care with debridement of necrotic material and the hyperkeratotic rim, eradication of infection, and mechanical offloading (e.g. bed rest, wheelchair, crutches, total contact casting, felted foam, orthotic shoes); additional options include hyperbaric oxygen and becaplermin gel (recombinant platelet-derived growth factor [PDGF]); patient instructions are provided in Table 86.3.

Table 86.3

Instructions for the patient with a diabetic or neuropathic ulcer.

Adapted with permission from Levin M, O’Neal ME. The Diabetic Foot. St Louis: Mosby, 1988.

Pressure (Decubitis) Ulcers (Bed Sores)

• Occur as a consequence of prolonged immobility, affecting ~10% of hospitalized patients and ~25% of nursing home residents; other risk factors include sensory deficits, older age, and poor nutrition.

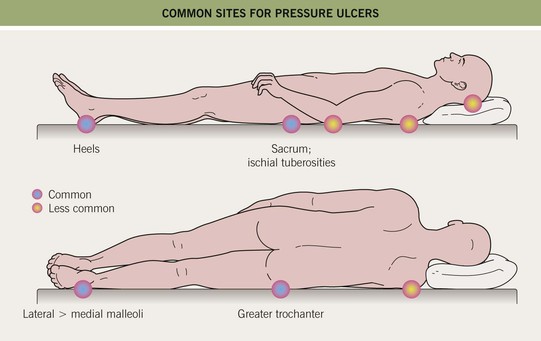

• Soft tissues are compressed between a bony prominence (e.g. sacrum, ischial tuberosity; Figs. 86.12 and 86.13) and an external surface; pathogenic factors include continuous pressure, shearing forces/friction, and moisture (e.g. perspiration, urine, feces).

Fig. 86.12 Common sites for pressure ulcers.

Fig. 86.13 Pressure ulcers. A Stage III ulcer over the sacrum. B Black eschar on the heel due to pressure necrosis. A, Courtesy, Ariela Hafner, MD, and Eli Sprecher, MD.

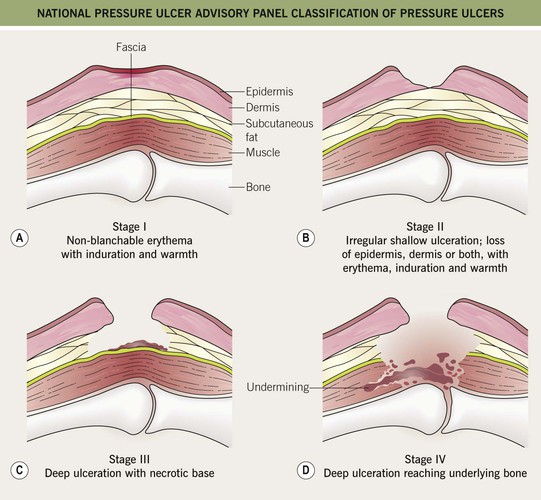

• Classified according to a four-stage system (Fig. 86.14); ulcers do not necessarily progress sequentially through these stages, and extensive deep tissue damage may initially have few superficial manifestations.

Fig. 86.14 National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel classification of pressure ulcers. A Stage I: nonblanchable erythema of intact skin. This lesion is the heralding sign of impending skin ulceration. For darker-skinned individuals, other signs may be indicators and include warmth, edema, discoloration of the skin, and induration. B Stage II: partial-thickness skin loss involving the epidermis, dermis, or both. This superficial lesion presents as an abrasion, blister, or shallow crater. C Stage III: full-thickness skin loss, in which subcutaneous tissue is damaged or necrotic and may extend down into, but not including, the underlying fascia. This deep lesion presents as a crater and sometimes involves adjacent tissue. D Stage IV: full-thickness skin loss and extensive tissue necrosis, destruction to muscle, bone, or supporting structures such as a tendon or joint capsule. Undermining or sinus tracts can be present.

Lymphedema

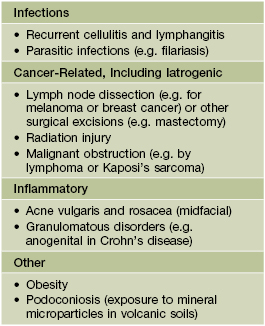

• Divided into primary forms due to abnormal lymphatic development (see Chapter 85) and secondary forms due to lymphatic damage or obstruction (Table 86.4).

• Usually presents as chronic, painless swelling and heaviness of an extremity (leg > arm), typically beginning distally (e.g. on the dorsal foot) and progressing proximally (Fig. 86.15); initially pitting, but becomes indurated and nonpitting as fibrosis develops; prone to ulceration and often worsens following secondary infections.

Fig. 86.15 Lymphedema. A Primary lymphedema of the upper extremities due to Milroy disease (see Chapter 85). B Lymphedema of the lower extremities secondary to morbid obesity and associated with myxedema. B, Courtesy, Ariela Hafner, MD, and Eli Sprecher, MD.

• Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa is a complication of severe lymphedema characterized by massive enlargement of the affected area, marked fibrosis, and verrucous epidermal changes with a mossy, cobblestoned appearance (Fig. 86.16).

Fig. 86.16 Elephantiasis nostras verrucosa. The patient had both lymphedema and venous insufficiency. Courtesy, Ariela Hafner, MD, and Eli Sprecher, MD.

• DDx: edema secondary to venous insufficiency, lipedema (bilateral lower extremity swelling that spares the feet, almost exclusively affecting women; Fig. 86.17), obesity-associated lymphedematous mucinosis.

Fig. 86.17 Lipedema. This middle-aged woman has bilateral ‘stovepipe’ enlargement of the legs and minimal involvement of the feet. Note the sharp demarcation between normal and abnormal tissue at the ankle, referred to as the ‘cuff sign.’ Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• Rx: difficult; compression (e.g. garments, wrapping), pneumatic pumps and massage to decrease accumulation of lymph; treatment of secondary infections.

General Approach to Wound Healing

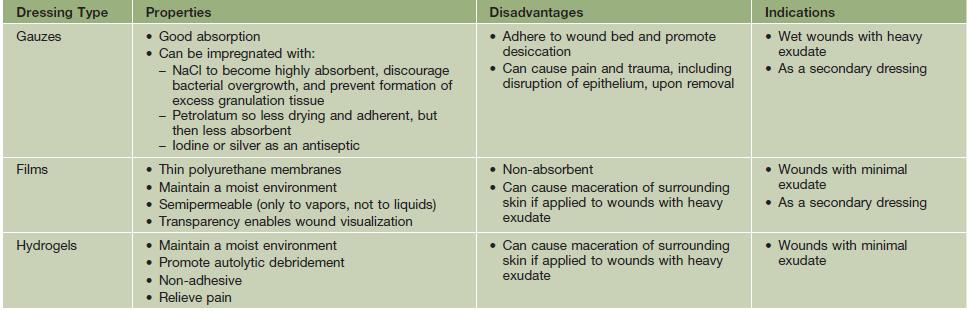

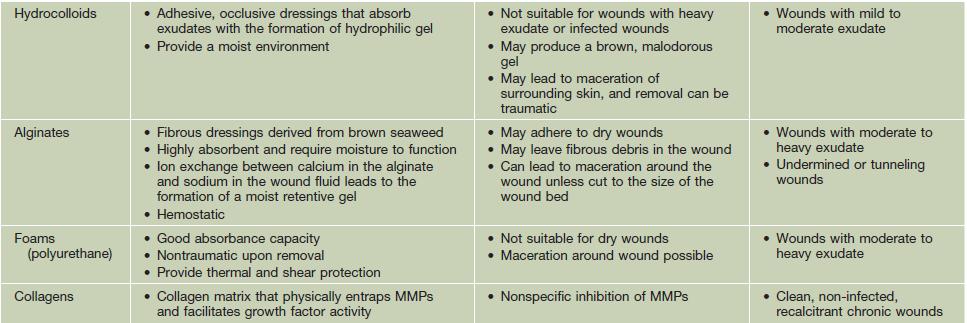

• The choice of dressing depends on the wound type and amount of exudate (Table 86.5), and it may be helpful to protect the skin around the wound with a thin coat of ointment to prevent maceration; the frequency of dressing changes is based on their absorbency as well as the amount of exudate.

Table 86.5

Types of wound dressings.

A conventional layered dressing usually has three components: (1) a nonadherent, fluid-permeable material that directly contacts the wound; (2) an absorbent layer (e.g. cotton pad or gauze); and (3) an outer wrap. However, some dressings (e.g. hydrocolloids) that are waterproof and adhere directly do not require secondary layers.

MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases.

Courtesy, Ariela Hafner, MD, and Eli Sprecher, MD.

• Debridement of nonviable tissue from the wound bed also promotes healing.

– Maggot debridement can be considered for recalcitrant ulcers with excessive necrotic tissue.

For further information see Ch. 105. From Dermatology, Third Edition.