Tumors of fat, muscle, cartilage, and bone

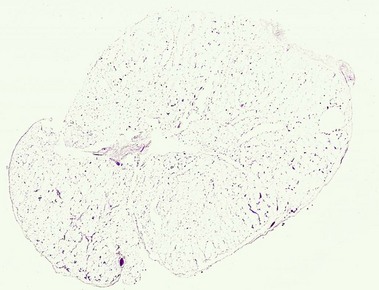

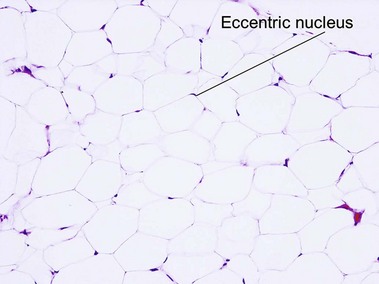

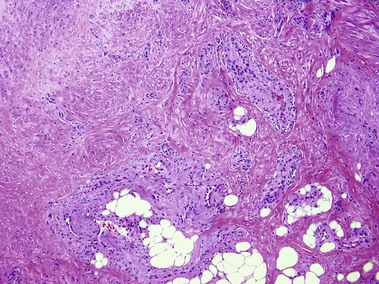

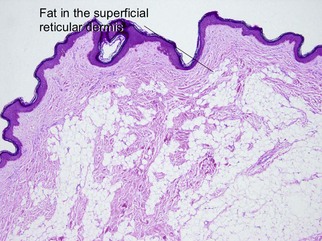

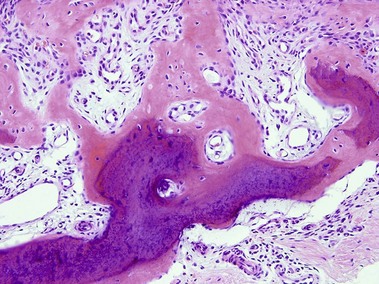

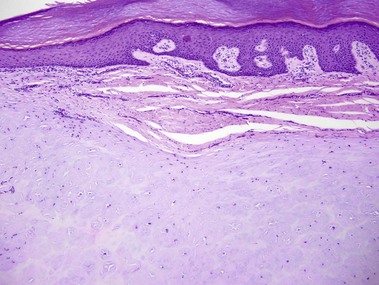

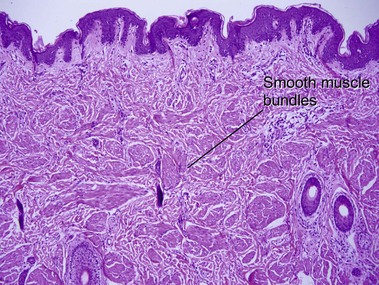

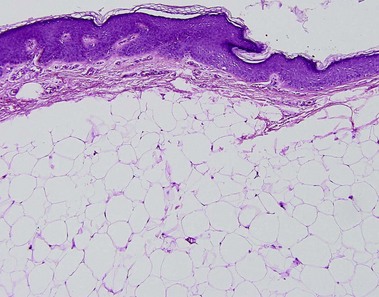

Nevus lipomatosis superficialis of Hoffmann and Zurhelle

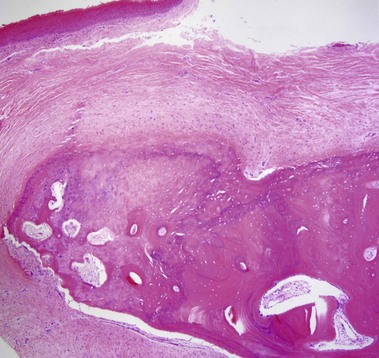

Large acrochordons with a broad base may have a similar appearance.

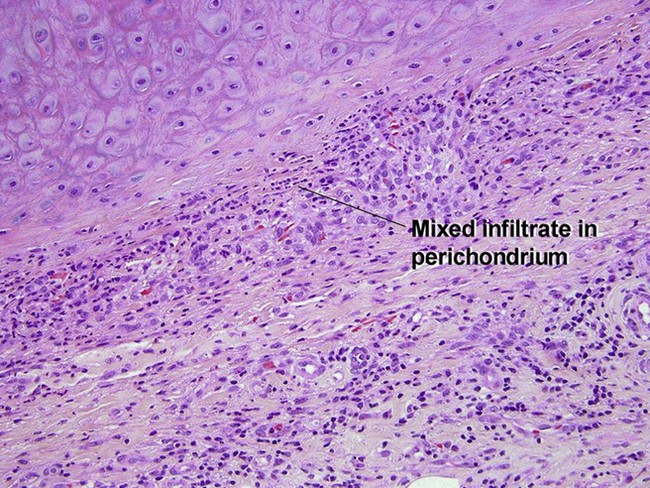

Relapsing polychondritis

Burgdorf, W, Nasemann, T. Cutaneous osteomas: a clinical and histopathologic review. Arch Dermatol Res. 1977; 260(2):121–135.

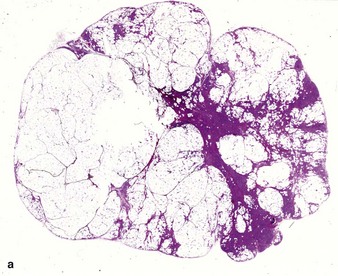

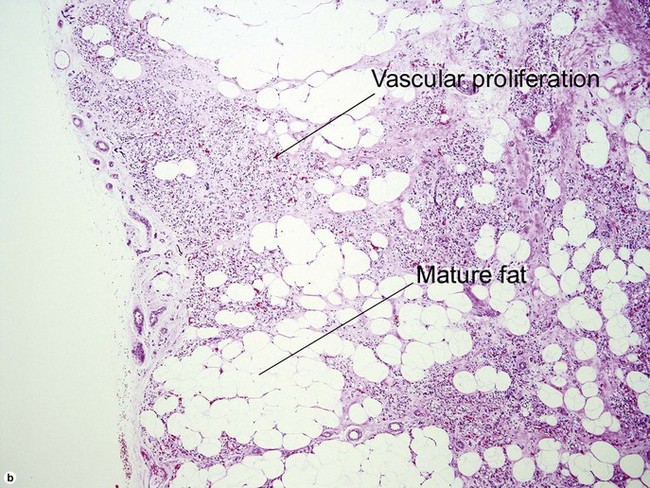

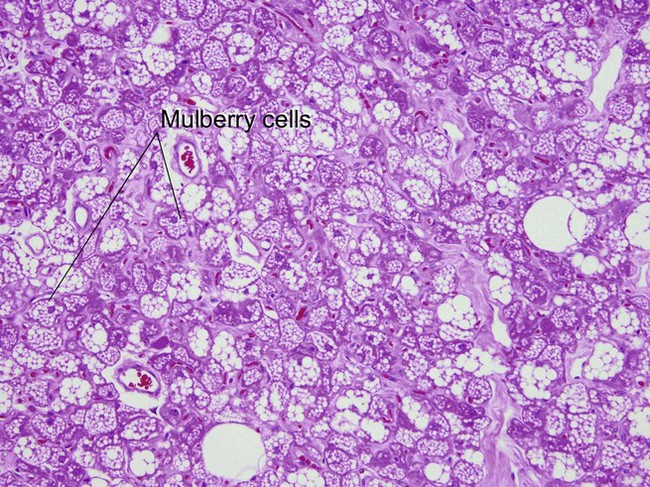

Dixon, AY, McGregor, DH, Lee, SH. Angiolipomas: an ultrastructural and clinicopathological study. Hum Pathol. 1981; 12(8):739–747.

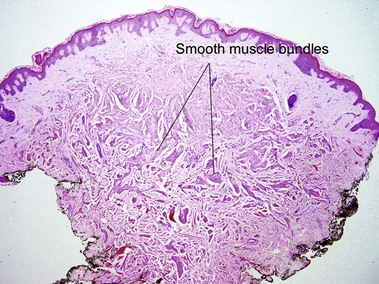

Fields, JP, Helwig, EB. Leiomyosarcoma of the skin and subcutaneous tissue. Cancer. 1981; 47(1):156–169.

Fletcher, CD, Martin-Bates, E. Spindle cell lipoma: a clinicopathological study with some original observations. Histopathology. 1987; 11(8):803–817.

Hachisuga, T, Hashimoto, H, Enjoji, M. Angioleiomyoma. A clinicopathologic reappraisal of 562 cases. Cancer. 1984; 54(1):126–130.

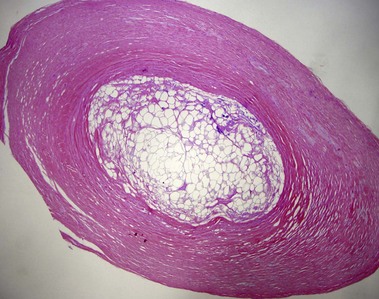

Hurt, MA, Santa Cruz, DJ. Nodular-cystic fat necrosis. A reevaluation of the so-called mobile encapsulated lipoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1989; 21(3 Pt 1):493–498.

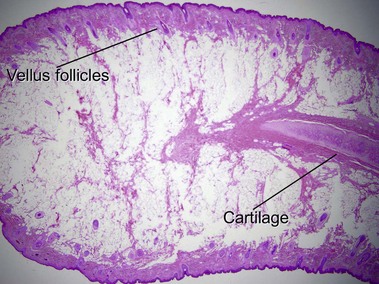

Jansen, T, Romiti, R, Altmeyer, P. Accessory tragus: report of two cases and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2000; 17(5):391–394.

Jensen, ML, Jensen, OM, Michalski, W, et al. Intradermal and subcutaneous leiomyosarcoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of 41 cases. J Cutan Pathol. 1996; 23(5):458–463.

Lee, SK, Jung, MS, Lee, YH, et al. Two distinctive subungual pathologies: subungual exostosis and subungual osteochondroma. Foot Ankle Int. 2007; 28(5):595–601.

Mehregan, AH, Tavafoghi, V, Ghandchi, A. Nevus lipomatosus cutaneus superficialis (Hoffmann-Zurhelle). J Cutan Pathol. 1975; 2(6):307–313.

Mehregan, DA, Mehregan, DR, Mehregan, AH. Angiomyolipoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992; 27(2 Pt 2):331–333.

Newman, PL, Fletcher, CD. Smooth muscle tumours of the external genitalia: clinicopathological analysis of a series. Histopathology. 1991; 18(6):523–529.

Raj, S, Calonje, E, Kraus, M, et al. Cutaneous pilar leiomyoma: clinicopathologic analysis of 53 lesions in 45 patients. Am J Dermatopathol. 1997; 19(1):2–9.

Roth, SI, Stowell, RE, Helwig, EB. Cutaneous ossification. Report of 120 cases and review of the literature. Arch Pathol. 1963; 76:44–54.

Shmookler, BM, Enzinger, FM. Pleomorphic lipoma: a benign tumor simulating liposarcoma. A clinicopathologic analysis of 48 cases. Cancer. 1981; 47(1):126–133.

Svoboda, RM, Mackay, D, Welsch, MJ, et al. Multiple cutaneous metastatic chordomas from the sacrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012; 66(6):e246–e247.

Thompson, J, Squires, S, Machan, M, et al. Cutaneous mixed tumor with extensive chondroid metaplasia: a potential mimic of cutaneous chondroma. Dermatol Online J. 2012; 18(3):9.