CHAPTER 92 Treatment of Intractable Vertigo

Classification of Vestibular Disorders

Vestibular disorders are classified as central or peripheral. Central disorders involve the brainstem and cerebellum, whereas peripheral disorders involve the vestibular nerve and labyrinth. The causes, symptoms, and treatments differ between the two categories. The hallmarks of each category are summarized in Table 92-1.1,2

| CHARACTERISTIC | CENTRAL VERTIGO | PERIPHERAL VERTIGO |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | Insidious | Sudden |

| Auditory symptoms (hearing loss, tinnitus, aural fullness) | Rarely present | Common |

| Neurologic deficits | Common | Rare |

| Severity of symptoms |

Central Vestibular Disorders

Vertebrobasilar Insufficiency

Patients with vertebrobasilar occlusive disease most commonly suffer from weakness in the extremities, ataxia, and oculomotor or oropharyngeal cranial nerve palsies. In these patients, vertigo is also a frequent finding.3 Patients with cerebellar infarctions may complain of vertigo, diplopia, nystagmus, nausea, and ataxic gait. Wallenberg’s syndrome, produced by unilateral infarction of the dorsolateral medulla, is manifested as vertigo, hoarseness, ataxia, Horner’s syndrome, and loss of pain and temperature sensation ipsilaterally in the face but contralaterally in the trunk and limbs.3 Subclavian steal syndrome is an unusual variant of vertebrobasilar insufficiency that may cause vertigo, although the association is controversial.4

Migrainous Vertigo

Migrainous vertigo is the second most common cause of recurrent vertigo and occurs in approximately 10% of all patients with migraine headaches. The disorder arises at any age and has a strong female preponderance.5,6 During acute episodes, patients often exhibit nystagmus and a Romberg sign. Auditory symptoms are rarely present, but vague ear fullness is rather common. The clinical findings may be quite variable, thus making precise diagnosis difficult, particularly given the fact that many times there is no associated headache. In fact, there is no broad consensus regarding diagnostic criteria for this disorder. Epidemiologic data indicate that (1) symptoms may be associated with typical migraine symptoms, including auras, photophobia, phonophobia, and severe headache; (2) the vertigo may be spontaneous or provoked by motion and last from seconds to several days; and (3) the temporal relationship between headache and the onset of vertigo may vary considerably. At present, there is no clear consensus regarding the treatment of migrainous vertigo, although many different therapeutic regimens have been studied.7

Tumors

Tumors of the cerebellopontine angle are rare but potentially important causes of vertigo. These tumors more commonly produce ataxia and disequilibrium; however, they are believed to produce vertigo by a variety of mechanisms, including compression of the cerebellum or brainstem, invasion of the bony labyrinth, compression of the membranous labyrinth, or neoplastic transformation of the vestibular nerve itself.8,9 Vestibular schwannomas, for instance, may cause unilateral hearing loss, tinnitus, and disequilibrium or vertigo, depending on the nature of the labyrinthine involvement. Intralabyrinthine schwannoma, a less common variant of vestibular schwannoma with only 47 reported cases since 1917, produces vertigo in the majority of patients.10

Paraneoplastic Syndromes

Several paraneoplastic syndromes have been associated with vertigo, probably through an autoimmune mechanism.11 Paraneoplastic encephalomyelitis is an autoimmune disease associated with small cell lung cancer. The disease is typically manifested as vertigo with other cranial nerve deficits secondary to degeneration of vestibular and cranial nerve nuclei. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration is associated with lung cancer, lymphoma, and breast and ovarian cancer. Patients experience rapidly progressive symptoms, including vertigo, ataxia, oscillopsia, diplopia, dysarthria, and dysphagia. Magnetic resonance imaging typically reveals atrophy of the cerebellum.12 In some cases the vestibular symptoms produced by these disorders may precede the diagnosis of malignancy.13

Demyelinating Disorders

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a relatively uncommon cause of central vertigo. Although dizziness is a frequent complaint of patients suffering from MS, only 5% to 10% of these patients experience true vertigo. Importantly, benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV) is frequently underappreciated in MS patients because the signs and symptoms of MS blur the distinction between central and peripheral causes of vertigo.14,15

Peripheral Vestibular Disorders

Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

BPPV is the most common cause of recurrent vertigo. It can occur throughout life, with the peak age at onset between the fifth and sixth decades. The annual incidence of BPPV is 107 cases per 100,000 population, and it is twice as common in women as in men. Risk factors for BPPV include a history of vestibular neuritis or head trauma, although most cases are idiopathic.16–20

BPPV is thought to result from canalithiasis in the majority of cases. Otoconia from the utricle dislodge and enter the endolymph of the semicircular canal system, most commonly the posterior semicircular canal, and stimulate flow of endolymph in response to changes in head position.17 An alternative form is cupulolithiasis, in which the dislodged otoconia adhere to the cupula ampullaris, thereby creating an abnormal mechanical stimulus that produces protracted deviation of the cupula in response to changes in the gravitational vector.21

Canalithiasis accounts for vertigo elicited by particular rotational movements of the head. Common positional triggers include lying down, extension of the neck to look up, bending forward, and sitting up from a supine position. A typical vertiginous episode lasts from 10 to 30 seconds and is often associated with nausea and visible nystagmus. Episodes of vertigo often occur in clusters with asymptomatic intervals between attacks. Several randomized placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated that a significant proportion of cases resolve spontaneously within a few months of onset, but the percentage of patients with self-limited cases varies considerably among these trials, ranging from 27% to 84%.21

BPPV caused by posterior semicircular canalithiasis may be revealed through the Dix-Hallpike maneuver. Proposed in 1952, this bedside maneuver quickly moves the patient from an upright seated to a supine position and then turns the patient’s head to one side and slightly extended at the neck. The procedure is then repeated by turning the head to the other side and observing the patient for nystagmus.21 Patients with horizontal canal BPPV may not demonstrate nystagmus with this maneuver.22

Meniere’s Disease

Endolymphatic hydrops, or Meniere’s disease, was first described by the Parisian physician Prosper Meniere in 1861.23 Meniere’s disease is relatively rare, with a prevalence of 218 per 100,000 persons. However, it is a relatively common cause of acute recurring episodic vertigo. Meniere’s disease may be overdiagnosed in the primary care setting.24–26

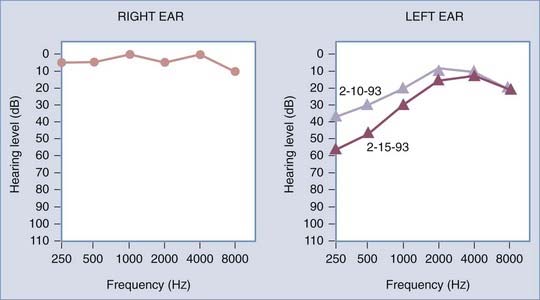

The classic manifestation consists of recurrent episodes of spontaneous rotational vertigo coupled with fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus, and aural fullness. The vertiginous episodes generally last several hours and are associated with nausea and vomiting. Hearing loss is typically progressive, predominantly affects the lower frequencies initially, and may ultimately lead to unilateral deafness (Fig. 92-1). Bilateral hearing loss develops in approximately 50% of patients.17 Management of bilateral cases is exceedingly complex.

Since its description, Meniere’s disease has been the subject of intense scientific inquiry. Even so, understanding its pathogenesis remains elusive. Current theories suggest that dysfunction of mechanisms governing the production and reabsorption of endolymph leads to distention and periodic rupture of the membranous labyrinth, which causes unilateral vestibular dysfunction. The cause of the dysfunction is unknown, although a viral insult in predisposed individuals has been proposed.2

Labyrinthitis

The most common cause of labyrinthitis is viral infection. Viral labyrinthitis is classically described as a sudden onset of severe vertigo associated with nausea, vomiting, and auditory symptoms, including tinnitus and hearing loss. Identification of the viral pathogens responsible for viral labyrinthitis is an ongoing scientific endeavor, the principal challenge being the demonstration of Koch’s postulates for a variety of presumptive agents.2,27

Bacteria can infiltrate the labyrinth through direct extension from a nearby focus of infection (otitis media, otomastoiditis, or meningitis) to cause a more serious form of labyrinthine infection. Serous labyrinthitis is characterized by the sudden onset of vertigo in association with otitis media, but it causes only mild to moderate hearing loss. Suppurative bacterial labyrinthitis results in severe hearing loss, vertigo, nausea, and vomiting. Patients with suppurative labyrinthitis often appear toxic and febrile.28 Although viral labyrinthitis is a self-limited condition, bacterial labyrinthitis requires intravenous antibiotics and sometimes urgent surgical labyrinthectomy to prevent serious complications such as meningitis. Permanent hearing loss is inevitable.

Vestibular Neuritis

The clinical manifestation of vestibular neuritis involves the acute onset of vertigo over a period of hours, which becomes quite severe for several days before it gradually subsides. There may be a flu-like prodrome. Auditory symptoms (tinnitus, aural fullness, and hearing loss) are characteristically absent, which helps distinguish the disorder from labyrinthitis.29 The most likely cause of vestibular neuritis is viral infection of the superior division of the vestibular nerve. Patients who suffer from vestibular neuritis are predisposed to secondary forms of BPPV, an association suggestive of a viral mechanism for otoconial displacement.

Vestibular neuritis is often described as a self-limited condition that persists for several weeks, depending on the rate of vestibular compensation. However, chronic morbidity is a significant problem given that 30% to 40% of patients will suffer from persistent dizziness secondary to incomplete vestibular compensation, a condition termed uncompensated vestibular neuritis.29,30 This distinction is particularly important for surgeons evaluating patients with intractable vertigo because patients with uncompensated vestibular neuritis are typically poor surgical candidates.

Perilymphatic Fistula

Perilymphatic fistula (PLF) is an abnormal connection between the fluid-filled inner ear and the air-filled tympanic cavity. First proposed a century ago by Meniere, PLF remains a controversial diagnosis among neuro-otologists.31 Previous studies have documented variable signs and symptoms, and it is often difficult to identify a definite site of leakage. Nonetheless, a recent meta-analysis of these studies has revealed certain clinical patterns: (1) patients complain of sudden loss or rapid deterioration of their hearing, (2) the hearing loss tends to involve fluctuations in speech discrimination, (3) dizziness is the most common symptom and is usually described as a continuous disequilibrium with occasional episodes of positional vertigo, and (4) most patients have a combination of symptoms.31–33 A significant proportion of documented cases exhibited the symptom constellation of fluctuating hearing loss, tinnitus, dizziness, and aural fullness. This clustering of symptoms is very similar to Meniere’s disease, thus confounding accurate diagnosis and treatment of these patients.34

Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence Syndrome

Superior semicircular canal dehiscence (SSCD) syndrome was first described in 2000. The putative pathophysiology of SSCD is thinning of the squamous temporal bone, which predisposes to dehiscence of the superior semicircular canal. In effect, acoustic energy is shunted away from the basilar membrane toward the structural defect in the otic capsule bone. SSCD syndrome is characterized by aural fullness, hyperacusis, autophony, and conductive or mixed hearing loss with a low-frequency component.35,36 Patients characteristically exhibit the Tullio phenomenon (noise-induced dizziness and eye movements) and the Hennebert sign (movement of the eyes in response to impulses of pressure in the external auditory canal). The sensitivity to loud sounds and changes in ambient pressure typically causes episodic vertigo and oscillopsia. On audiometric testing, bone conduction thresholds in the involved ear are better than in the other and may be supranormal in the low frequencies. Acoustic reflexes are present despite the apparent conductive hearing loss. Thin-section temporal bone computed tomography (CT) scans reformatted in the plane of the superior canal are diagnostic. Electrocochleography and vestibular evoked myogenic responses are particularly helpful in confirming the diagnosis in patients with a suspicious clinical picture or borderline CT findings.

Trauma

Trauma can cause either peripheral or central vertigo, depending on the mechanism of injury. Head trauma can lead to vertigo by a variety of mechanisms, including fracture of the temporal bone, creation of epileptogenic foci, induction of posttraumatic migraine, and alteration in the vertebrobasilar circulation. Transverse fractures through the temporal bone may cause disruption of the membranous labyrinth or significant damage to the cochleovestibular nerve, or both, thereby provoking severe vertigo and profound sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL). In addition, trauma patients with labyrinthine injury will experience gait unsteadiness and veering toward the affected side for several days, along with nausea and vomiting. These symptoms usually subside within 6 weeks. Longitudinal temporal bone fractures, which typically spare the membranous labyrinth and cranial nerve VIII, can still produce vertigo and disequilibrium via shearing forces or a concussive injury to the labyrinth itself. Other potential features of temporal bone fractures include discomfort about the temporomandibular joint, facial nerve palsy, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) otorrhea.37 Posttraumatic epilepsy occurs in approximately 5% of patients with closed head injuries. Damage to the temporal lobe, in particular, may establish epileptic foci that cause the sensation of vertigo during seizures. Alterations in the vertebrobasilar arterial circulation may occur after trauma and predispose patients to basilar artery migraine, which may produce migrainous vertigo.38

Of note, head trauma patients are also susceptible to the development of BPPV and PLF. A recent study indicated that approximately 50% of traumatic brain injury patients who complain of positional vertigo actually have BPPV.39

Neck trauma, especially whiplash injury, can cause vertigo and disequilibrium. The onset of dizziness occurs 7 to 10 days after the traumatic event, and symptoms may persist for several years. Patients typically complain of neck pain and tenderness, as well as recurrent positional vertigo and visual disturbances triggered by rotation of the head. One putative mechanism is vertebrobasilar insufficiency, but a recent study of magnetic resonance angiography in patients with whiplash injury and vertigo yielded inconclusive results.40 It is also possible that the dizziness is mediated by a pathologic disturbance in the vestibulocollic reflex despite its relative lack of importance in healthy humans.

Nonsurgical Management of Vertigo

Vestibular Rehabilitation

Vestibular rehabilitation is a cornerstone of the treatment of many vertiginous disease processes and is particularly important in the postsurgical phase of recovery. The concept of vestibular rehabilitation for patients with iatrogenic unilateral loss of vestibular function or postconcussive disorders was first implemented in the 1940s by Cawthorne and Cooksey.41–43 Since that time, vestibular rehabilitation exercises have become more tailored to the individual patient, thereby increasing therapeutic efficacy, although some of the original exercises proposed by Cawthorne and Cooksey are still used by rehabilitation specialists today. There is considerable evidence to suggest that vestibular rehabilitation alone or in conjunction with other therapeutic modalities is highly efficacious in the treatment of a wide variety of vestibular disorders.44–48 However, the efficacy of vestibular rehabilitation can be compromised in the following situations: (1) bilateral loss of vestibular function, (2) central vestibular dysfunction or oversedation, (3) unstable conditions with fluctuating or progressive symptoms, and (4) medical comorbid conditions that affect proprioceptive or visual input to the central nervous system.43 Thus, patients with stable, unilateral lesions affecting the periphery of the vestibular system are most amenable to a program of vestibular rehabilitation, whereas those with central disorders require longer treatment periods and have poorer outcomes.43,44,49,50

Canalith Repositioning Maneuvers

BPPV is unusual relative to other forms of vertigo, and this condition can be promptly and effectively treated at the bedside with a series of canalith repositioning maneuvers, which were popularized by Epley in 1992.21,51,52 The objective of these maneuvers is to mobilize the displaced otoconial debris from the affected semicircular canal via a sequence of head positioning maneuvers such that the debris ultimately settles in the utricle. A meta-analysis concluded that the Epley maneuver is a safe and effective treatment strategy for BPPV in the short term, although the authors qualified this assertion with the fact that BPPV has a high rate of natural resolution and thus a type II error was possible. Moreover, there is no evidence that the Epley maneuver constitutes a definitive cure for BPPV because recurrences are common and there is a paucity of long-term follow-up of these patients.21

Pharmacologic Therapy

Glutamate appears to be the most important neurotransmitter of vestibular afferent impulses, although acetylcholine transmission via muscarinic receptors also plays a role. Histamine and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptors are also present in the vestibular nuclei. Most of the pharmacologic agents used for the treatment of vertigo are vestibular suppressants that exploit the known neurochemistry of the vestibular system, and such medications include benzodiazepines, antihistamines, and anticholinergic agents. In general, these drugs are designed to reduce the intensity of vertiginous spells and have little prophylactic benefit. The major side effect is sedation, although benzodiazepines have the additional side effect of respiratory depression in high doses. Vestibular suppressants should not be used on a chronic basis because they impair the process of vestibular compensation, and many of these medications foster physiologic dependence.53

Benzodiazepines potentiate the inhibitory action of GABA, thereby reducing pathologic vestibular input to the central nervous system. Benzodiazepines are considered by many clinicians to be the first line in the pharmacologic armamentarium for vertigo because they are the most effective class of medications for this symptom. Lorazepam and diazepam are particularly effective for the treatment of acute exacerbations of Meniere’s disease. The nongeneric form of lorazepam (Ativan) has the advantage of a sublingual delivery mode, which is valuable for patients with considerable nausea and emesis. Sometimes benzodiazepines are used for symptomatic management in the acute phase of a vestibular crisis caused by labyrinthitis or vestibular neuritis. Although benzodiazepines may actually facilitate the early stages of central compensation by helping mobilize the patient earlier,54 patients should not continue this medication after the acute symptoms resolve to avoid physiologic dependence and permit vestibular compensation to proceed to completion.

Meclizine, dimenhydrinate, diphenhydrinate, and promethazine are type 1 histamine receptor antagonists. The mechanism by which these drugs reduce the severity of vertigo is unclear but most likely involves antagonism of either histamine receptors in the vestibular nuclei or central cholinergic activity. These drugs must cross the blood-brain barrier for therapeutic effect; thus, second-generation antihistamines are not efficacious in the treatment of vertigo. Meclizine is the most popular choice among clinicians, especially for Meniere’s disease.53

Currently, there is no evidence to support the use of antiviral medications for the treatment of vestibular neuritis despite the viral etiology of this disorder. A recent German study involving methylprednisolone and valacyclovir failed to show any therapeutic benefit from valacyclovir alone, although a benefit was observed with methylprednisolone.55 These findings have been corroborated by the work of Ariyasu, Morales-Luckie, and others, who demonstrated that oral steroids reduce the severity of vertiginous spells and expedite recovery from an acute episode of vestibular vertigo.56,57

Although Meniere’s disease is amenable to vestibular suppressants, the best conservative treatment strategy for this disorder consists of salt restriction and diuretics, both of which minimize hydropic change within the membranous labyrinth.58 The target range for salt consumption is 1.5 to 2 g daily. A dietitian can help patients select the appropriate foods to meet this objective. Patients should be advised that the therapeutic benefit of salt restriction may not become evident for several weeks. Some patients note that certain substances such as caffeine and nicotine may exacerbate their symptoms. Thiazide diuretics reduce the frequency of vertiginous spells in patients with Meniere’s disease but have a variable effect on hearing loss.59,60 Triamterene, a potassium-sparing diuretic, can be administered when thiazide diuretics are contraindicated. Generally, a combination of triamterene and hydrochlorothiazide is prescribed and continued for 3 to 6 months after resolution of the acute spells.

Currently, there is no consensus concerning the treatment of migrainous vertigo. Medications that are ordinarily administered for migraine prophylaxis (beta blockers, calcium channel blockers, tricyclic antidepressants, pizotifen, and flunarizine), as well as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, have been used in the setting of migrainous vertigo with some degree of success.7,61

Surgical Management of Intractable Vertigo

Surgery for Benign Paroxysmal Positional Vertigo

BPPV often resolves spontaneously and is characteristically amenable to simple bedside maneuvers; however, in rare circumstances the condition is refractory to conservative therapies and is so debilitating that surgical intervention is warranted.62 There are two invasive modalities for the treatment of refractory BPPV: singular neurectomy and posterior semicircular canal occlusion.

Singular Neurectomy

Singular neurectomy involves transection of the posterior ampullary nerve (also known as the singular nerve), a branch of the inferior vestibular nerve that innervates the ampulla of the posterior semicircular canal. In effect, the procedure eliminates vestibular input from the posterior semicircular canal containing displaced otoconial debris. The procedure itself is technically challenging because it requires considerable expertise in temporal bone dissection and carries a significant risk for permanent SNHL. Gacek developed the procedure in the early 1970s. Since its inception, 342 singular neurectomies have been reported, the lion’s share by Gacek himself. According to his series, hearing was preserved in 97% of cases, but hearing outcomes have been markedly worse in other published studies by surgeons who have less experience with this procedure.62,63

Posterior Semicircular Canal Occlusion

Posterior semicircular canal occlusion was developed in 1990 by Parnes and McClure.64 The procedure involves exposure of the posterior semicircular canal via the mastoid, with subsequent permanent obstruction of the canal to eliminate the flow of endolymph, which secondarily renders the cupula unresponsive to angular acceleration. Of the 97 patients reported in the literature, 94 experienced complete cure and only 4 had postoperative hearing loss.62,65 Both singular neurectomy and posterior semicircular canal occlusion are relatively rare procedures, increasingly so as the Epley maneuver has become more standardized in practice. Nonetheless, posterior semicircular canal occlusion appears to be the safer approach to intractable BPPV.62

Surgery for Superior Semicircular Canal Dehiscence Syndrome

In some cases, SSCD syndrome can be managed simply by having the patient avoid stimuli that provoke symptoms. In cases characterized by sensitivity to changes in pressure, placement of a tympanostomy tube on the affected side reliably alleviates the symptoms. However, for some patients, avoidance of provocative stimuli is impossible and the sound- and pressure-induced symptoms are so debilitating that surgery is indicated.35

The conventional surgical treatment of SSCD addresses the bony defect by means of middle fossa craniotomy and plugging of the defect or by resurfacing with fascia and a bone graft from the craniotomy site. The former approach is more effective at controlling vertigo—the reported cure rate is approximately 95%—but the effect on preexisting conductive hearing loss is less predictable.66,67

Surgery for Perilymphatic Fistula

The definitive strategy for managing PLF has yet to be fully established, mostly because the diagnostic criteria for this enigmatic disease remain so elusive. There is no “gold standard” for diagnosis of PLF,34,68–72 and firm clinical criteria for surgical intervention have yet to be developed. Despite this lack of consensus, management of this disorder entails a graduated approach toward surgical intervention, as guided by the level of clinical suspicion. Penetrating injuries of the middle ear should be explored promptly, as should patients who have previously undergone stapedectomy. Nonsurgical management of suspected acute PLF associated with head trauma or barotrauma can lead to full resolution of symptoms.49 Conservative therapy for PLF consists of 1 week of bed rest with 30-degree elevation of the head. Patients should avoid activities that involve straining or lifting during this time because the Valsalva maneuver can exacerbate symptoms. Conventional medications for the treatment of vertigo, including benzodiazepines, scopolamine, and antiemetics, can be quite effective in the interval. If suspicion of PLF is low and hearing is stable, a therapeutic trial of vestibular rehabilitation is indicated. Patients who fail to improve with these therapeutic measures are candidates for surgical intervention. The classic surgical approach for PLF involves patching the oval or round window with a graft of earlobe fat, temporalis fascia, or tragal perichondrium. Notably, positive studies report that 90% of selected patients experience some improvement in their vestibular symptoms, but the effect of surgery on hearing is far less predictable.31,73–75

Surgery for Meniere’s Disease

Intratympanic Injection of Gentamicin

Intratympanic injections of gentamicin exploit the selective vestibulotoxicity of this drug by suppressing vestibular function while preserving the patient’s residual hearing in the affected ear. Low doses of gentamicin damage cells in the vestibular apparatus that are involved in ionic regulation and endolymph production; thus, targeted destruction of these cells can theoretically ameliorate hydropic change within the membranous labyrinth. Higher dosages decrease the selective vestibulotoxicity of the drug, thereby causing irreversible damage to hair cells and permanent SNHL.73,75

Intratympanic delivery of aminoglycosides was first described by Schuknecht in 1957 and, despite the inherent risk for SNHL, is widely used by otolaryngologists today for the treatment of medically refractory Meniere’s disease. The drug may be delivered by direct injection through the tympanic membrane or by placement of a ventilation tube in the tympanic membrane through which the drug can be intermittently dosed.76 A variety of dosing patterns have been proposed. A recent meta-analysis that compared the various dosing regimens demonstrated that the “titration method” has the highest vertigo control rates coupled with a relatively low incidence of hearing loss.39 The efficacy and relative safety of intratympanic gentamicin injections have led to a significant decline in the popularity of more invasive surgical approaches.77,78

Meniett Device

The observation that changes in ambient pressure could improve vertiginous symptoms in patients with Meniere’s disease provided the necessary impetus to develop the Meniett device, a machine that generates intermittent pressure impulses that reach the inner ear through a tympanostomy tube.79 The precise mechanism by which the device ameliorates the symptoms of Meniere’s disease is unclear. One plausible explanation is that pressure impulses from the machine reach the inner ear via the round window and cause a reduction in the volume of endolymph, possibly by increasing flow through the utriculoendolymphatic valve. Recent studies by Gates and colleagues have demonstrated a significant reduction in the severity and frequency of vertiginous symptoms in patients using this device.80,81

Endolymphatic Sac Surgery

Endolymphatic sac surgery is a highly controversial surgical approach to the management of intractable Meniere’s disease. The French otologist Georges Portmann introduced the procedure in 1927, which entails fenestration of the endolymphatic sac to decompress the endolymph. The procedure has undergone several minor suggested technical modifications since its inception.82–86 A review of the literature to date, which involves 1880 documented cases, reveals an initial vertigo control rate of 86% with improved hearing in 22%, although hearing was adversely affected in 25% of patients. Other potential complications of this procedure include CSF leak and injury to the facial nerve.85

The crux of the controversy surrounding endolymphatic sac surgery arises from a seminal study by Thomsen and colleagues in 1981 that compared endolymphatic sac surgery with a “sham” cortical mastoidectomy in a double-blind, controlled manner.87 The study demonstrated no statistically significant difference in outcome between the two approaches.87–89 The logical conclusion from these data is that the reported efficacy of endolymphatic sac surgery is merely a placebo effect. Some authors have theorized that the observed effect is a reflection of the natural history of Meniere’s disease, which despite the progressive deterioration of hearing toward permanent SNHL, tends to gradually resolve vis-à-vis the vestibular symptoms.90 A nonspecific effect from anesthesia itself may also be a factor in the improvement noted after endolymphatic sac surgery.91

Welling and associates reanalyzed the data from these trials with modern statistical methods and did find statistically significant differences between the placebo and experimental groups with respect to postoperative dizziness and tinnitus that favored endolymphatic sac surgery.85 Furthermore, the authors pointed out the inadequate statistical power of Thomsen and associates’ original study, which may have precluded the detection of potentially significant differences in outcomes beyond dizziness and tinnitus. Given the controversy surrounding the efficacy of endolymphatic sac procedures relative to the natural history, some otologists do not believe that adequate evidence exists to support the use of endolymphatic sac surgery for control of vertigo in patients with Meniere’s disease.

Vestibular Ablative Surgery

Vestibular ablative surgery is designed to eliminate residual labyrinthine function in the pathologic ear. In general, ablation is reserved for patients who have failed medical therapy and can adequately compensate for unilateral loss of vestibular function because the procedures themselves lead to transient worsening of symptoms in the postoperative phase. Vestibular ablative surgery entails two distinct approaches: vestibular neurectomy and labyrinthectomy. The fundamental difference between the two is that labyrinthectomy obliterates residual hearing in the affected ear, whereas most approaches to vestibular neurectomy are designed to preserve it. Even so, vestibular neurectomy carries an inherent risk for injury to the cochlear nerve with resultant hearing loss. These surgeries are most commonly performed to control vertigo in cases of intractable Meniere’s disease; however, they can be used in other clinical scenarios involving unstable or progressive unilateral vestibulopathy.92,93

Considerations for Ablative Surgery

Careful selection of patients for vestibular ablative surgery is absolutely central to securing a satisfactory outcome. Vestibular neurectomy is the preferred approach in patients wishing to preserve residual hearing in the affected ear. However, these patients should be advised that vestibular ablation does not completely halt the natural progression of Meniere’s disease with respect to progressive SNHL. In fact, profound SNHL may ultimately occur even after vestibular neurectomy with no postoperative complications. Furthermore, vestibular neurectomy carries a distinct set of risks that are not associated with labyrinthectomy, which must be weighed against the potential benefits of preserved residual hearing.94,95

Accurate identification of the pathologic labyrinth is an important component of the preoperative evaluation. Fluctuating or progressive asymmetric hearing loss is an excellent indicator of the affected side, even if the hearing loss has preceded vertigo by an extended period. Likewise, unilateral reduction of responsiveness to caloric irrigation is usually a reliable lateralizing sign.96,97 Poorer indicators of the affected ear include tinnitus, aural fullness, the direction of nystagmus, and rotary chair asymmetries. Tinnitus and aural fullness in the patient’s better functioning ear may signify contralateral extension of the disease process. This should be viewed as a relative contraindication to these surgical approaches.

In addition to lateralizing the pathology, the potential for central vestibular compensation must be assessed because this factor markedly affects surgical outcome. Patients experience transient worsening of their symptoms postoperatively, and recovery is ultimately predicated on the patient’s ability to compensate centrally. In general, stable vestibular pathology in the setting of incomplete central compensation, including impaired vestibular compensation secondary to central extension of the disease process, is a contraindication to ablative surgery. Persistence of spontaneous or positional nystagmus, rotational chair asymmetry, or sensory organization test abnormalities on dynamic posturography is indicative of incomplete central compensation. Such patients should undergo a complete trial of vestibular rehabilitation.98

Labyrinthectomy

Although labyrinthectomy was commonly used for treating suppurative labyrinthitis in the late 1800s, the first labyrinthectomy specifically for vertigo was performed in 1904 by Lake and Milligan, two British otolaryngologists.99,100 Cawthorne and Schuknecht helped popularize labyrinthectomy as a treatment specifically for Meniere’s disease in the 1940s and 1950s.101,102 Indeed, for much of the 20th century, labyrinthectomy was a mainstay in the treatment of medically refractory vertigo, principally because of its safety and high efficacy. However, the predominance of labyrinthectomy has been challenged in the past 30 years with the advent of intratympanic injections of gentamicin and vestibular neurectomy, both of which appear to be highly efficacious and relatively safe, with the theoretical advantage of preservation of hearing.

Labyrinthectomy is appropriate for patients who have intractable vertigo secondary to a unilateral vestibular disorder with severe to profound SNHL on the affected side. There are two approaches to this procedure: the transcanal (sometimes termed oval window labyrinthectomy) and the transmastoid approach. The former involves a less invasive approach through the external auditory canal but does not reliably ablate vestibular function.103 The latter is widely regarded as the gold standard for vestibular ablation because it allows the surgeon to completely visualize and remove the membranous labyrinth (semicircular canals, utriculus, and sacculus). The procedure is highly efficacious, with published control rates for vertigo exceeding 90%, but it requires expertise in transtemporal surgical approaches, including detailed knowledge of the complex neurovascular and labyrinthine anatomy of the temporal bone.104–108

The principal disadvantage of labyrinthectomy via the transcanal or transmastoid approach is complete ipsilateral hearing loss, although this concern is negligible in patients with profound SNHL preoperatively. The most important postoperative complications associated with labyrinthectomy include a very low risk for injury to the facial nerve and CSF leakage.108 All patients who undergo labyrinthectomy must subsequently endure a transient period of worsening disequilibrium that typically subsides within 2 months, provided that vestibular compensation proceeds as anticipated. However, in some patients the disequilibrium becomes chronic, an adverse outcome that probably results from poor vestibular compensation or active disease in the contralateral ear. The former is a significant concern in the elderly, who have a higher frequency of prolonged postoperative disequilibrium than younger patients do.108

Vestibular Nerve Section

The first sectioning of the eighth cranial nerve in a patient with vertigo was performed by R. H. Perry in the early 1900s.109 Despite several attempts by different surgeons around the turn of the century, the high morbidity and mortality associated with the operation caused most surgeons to abandon the procedure in favor of labyrinthectomy. Walter Dandy and Kenneth George McKenzie revitalized neurectomy as a viable surgical option for the treatment of intractable vertigo. They developed the concept of selective vestibular neurectomy (i.e., division of the vestibular nerve with sparing of the cochlear nerve) by performing this operation in the 1930s and early 1940s on hundreds of patients with Meniere’s disease; they boasted cure rates for vertigo that exceeded 90% with a low rate of postoperative facial paresis and only two deaths postoperatively.77,110–112 Despite this remarkable success, contemporary surgeons were more comfortable with transmastoid labyrinthectomy than with the craniotomy associated with vestibular neurectomy.78 In effect, labyrinthectomy and endolymphatic sac surgery remained the preferred surgical approaches for the treatment of intractable vertigo until the advent of a microsurgical extradural approach to the internal auditory canal and improved neuroanesthesia in the latter half of the 20th century, which ushered in multiple technical variations of vestibular neurectomy.77,78

In theory, selective sectioning of the vestibular nerve spares the cochlear nerve and thus residual hearing in the affected ear. In practice, outcomes with respect to postoperative hearing loss are quite variable, which may reflect a technical flaw inherent in the operations themselves. Currently, there are several different approaches to selective vestibular neurectomy: middle fossa neurectomy (MFVN), retrolabyrinthine neurectomy (RLVN), retrosigmoid neurectomy (RSVN), combined retrolabyrinthine/retrosigmoid neurectomy (RRVN), and endoscopically assisted. The best approach remains a subject of controversy, especially given the surgical community’s historical preference for labyrinthectomy and the increasing popularity of intratympanic injections of gentamicin. Each technique has its own advantages and disadvantages. In general, postoperative hearing loss is a significant concern with MFVN, but less so with the posterior fossa approaches. The technical details of these operative approaches are beyond the scope of this chapter, and detailed discussion is available elsewhere.78,113

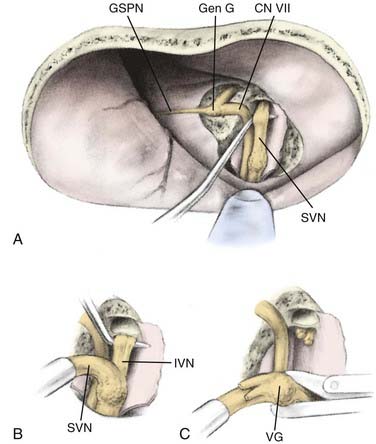

Middle Fossa Vestibular Neurectomy

In the 1960s, House proposed an extradural approach to the internal auditory canal in which the superior vestibular nerve could be transected.114 In the 1970s, Fisch, Glasscock, and others extended the dissection to include transection of not only the superior vestibular nerve but also the inferior division and removal of Scarpa’s ganglion. These additions improved the efficacy of MFVN significantly (Fig. 92-2).78 MFVN entails a preauricular craniotomy followed by drilling of the bony roof of the internal auditory canal to expose the branches of the vestibular nerve, which are sectioned.

Published vertigo control rates after complete sectioning of the vestibular nerve range from 94% to 98%, which rivals the efficacy of labyrinthectomy and other forms of selective vestibular neurectomy. Selective division of the superior vestibular nerve (sparing innervation to the posterior semicircular canal) reduces the efficacy considerably, with reported control rates ranging from 72% to 78%, but leads to better preservation of residual hearing than total sectioning does.115,116 Although the middle fossa approach can be efficacious, the procedure is quite challenging from a technical standpoint because it involves dissection in a very delicate portion of the temporal bone in close proximity to the inner ear, the cochlear blood supply, and the facial nerve. In effect, the principal disadvantages of the middle fossa approach include relatively high rates of postoperative hearing loss and transient facial paresis (21% to 24% and 6% or higher, respectively).115–118 Because of the technical difficulty of the approach and the relatively high rates of hearing loss and facial weakness, MFVN never gained widespread popularity in the United States or Europe.78

Retrolabyrinthine Vestibular Neurectomy

In light of the technical difficulties associated with MFVN, a posterior fossa approach was developed in the 1970s that offered retrolabyrinthine exposure of the eighth cranial nerve in the cerebellopontine angle with less cerebellar retraction than needed for RSVN. The retrolabyrinthine approach was first described by Hitselberger and Pulec in 1972 in a case report involving a patient with trigeminal neuralgia. Silverstein, however, developed the retrolabyrinthine approach as a viable surgical treatment of intractable vertigo by performing the first RLVN procedure in 1977.119,120 In effect, the posterior fossa approach has become the most popular technical variation of vestibular neurectomy and accounts for approximately 95% of all vestibular neurectomies performed in the United States (Fig. 92-2).78

RLVN appears to be quite effective, although its efficacy is dependent on the cause of the unilateral vestibulopathy. Kemink and Hoff reported complete resolution of vertigo in 92% of patients in whom Meniere’s disease was diagnosed, but in only 77% of those with other causes.93 Cure rates in other published studies are more variable but consistently show a statistically significant difference in efficacy between patients with Meniere’s disease (76% to 97%) and those with other causes (28% to 77%).78,93,118,119,121–128

The potential advantages of RLVN include a lower rate of facial nerve injury and postoperative hearing loss than with the middle fossa approach, which stems from the relative technical safety of the transtemporal approach used for RLVN.93,120,129 One series of 50 patients demonstrated no instances of facial paresis, an improvement over the middle fossa approach.93 Proponents of RLVN claim a lower rate of postoperative hearing loss than seen with MFVN. The results of Kemink and Hoff, which demonstrated hearing preservation in 92% of patients, support this claim.93 However, other studies have yielded considerable variability with respect to hearing loss (7% to 58% of patients).78,93,118,119,121–128 A confounding factor in the analysis is that the natural history of Meniere’s disease is one of progressive SNHL, which is probably unaffected by these surgical interventions. However, some authors have theorized that accumulation of bone dust in the oval window during the procedure may contribute to the hearing loss and account for some documented cases of SNHL in the immediate postoperative period.127,130

There are several disadvantages to RLVN. One drawback is that the eighth cranial nerve is exposed only within the cerebellopontine angle, where it can be difficult to discern cochlear from vestibular nerve fibers. This raises the possibility of incomplete vestibular ablation or inadvertent sectioning of auditory nerve fibers, both of which are corroborated by the significant variability in published outcomes. In addition, postoperative CSF leakage occurs in 4% to 12% of patients, significantly more commonly than in patients who undergo RSVN.78,118,119,121–128,130 The incidence of wound infection and aseptic meningitis is similar to that of RSVN, with these complications occurring in less than 5% of patients.

Retrosigmoid Vestibular Neurectomy

Dandy and McKenzie developed RSVN in the 1930s. The procedure entails a posterior fossa craniotomy with incision of the dura posterior to the sigmoid sinus and retraction of the cerebellum to expose the eighth cranial nerve in the cerebellopontine angle. The principal advantage of this approach, when compared with RLVN, is that it permits watertight closure of the dura more frequently, thereby reducing the risk for CSF leakage to less than 4%.131 Like RLVN, exposure of the eighth cranial nerve in the cerebellopontine angle can be suboptimal, which raises the specter of inadvertent damage to the cochlear nerve. The published data relate an incidence of postoperative hearing loss of 7% to 45% after RSVN.123,132,133 Nevertheless, RSVN appears to be quite efficacious in the treatment of vertigo. Follow-up of Dandy’s extensive series of more than 600 cases demonstrated cure rates ranging from 75% to 90%.

The principal disadvantage of any retrosigmoid approach is the considerable risk for postoperative headache—approximately 1 in 10 patients, although an incidence as high as 50% has been reported.123,134–136 The cause of postoperative headache remains a subject of continued debate in the surgical community, but several theories have been proposed. Some believe that adhesion of the cervical musculature to the dura, a natural consequence of the suboccipital craniectomy, leads to traction on the dura with head movement. Others have postulated that bone dust in the subarachnoid induces a chemical meningitis or interferes with resorption of CSF. Alternatively, injury to the greater and lesser occipital nerves during incision or retraction may be the cause. Other complications associated with RSVN include CSF leakage, wound infection, and aseptic meningitis, although the risk for these complications is less than 5%.135

RSVN has undergone several technical modifications since its inception, some of which were fueled by a desire to circumvent the issue of severe postoperative headache. Silverman and associates altered the primary incision and closure and omitted any drilling of the internal auditory canal, with a resultant decrease in the incidence of postoperative headache to 3.8% 2 years after surgery.135 Fukuhara and colleagues simply drained 60 to 90 mL of CSF through a lumbar drain preoperatively and reduced the incidence of postoperative headache to 3.6%.137 Several authors have performed cranioplasty with calvarial bone grafts or other material to avoid dural adhesions, but the benefit of this maneuver vis-à-vis postoperative headache is controversial.138,139

To address the problem of suboptimal exposure of the vestibular nerve in the cerebellopontine angle, Silverstein and coworkers modified RSVN in the mid-1980s by adding an approach to the internal auditory canal (RSVN-IAC). Like RSVN, a retrosigmoid craniotomy is performed to access the nerve in the angle. A dural flap is then elevated from the temporal bone, and the posterior wall of the internal auditory canal is drilled to expose the superior vestibular and singular nerves for selective division distal to their separation from the cochlear fibers. The advantage of this approach when compared with RSVN is the potential for more definitive sectioning of the vestibular branches with less risk to the cochlear nerve. In practice, these technical modifications have resulted in excellent control of vertigo (approximately 90% of patients) with a low incidence of CSF leakage, but the incidence of severe postoperative headache was markedly increased, thus curbing enthusiasm for this approach.78,134,140

Combined Retrosigmoid–Internal Auditory Canal/Retrolabyrinthine Vestibular Neurectomy

In the late 1980s, Silverstein and colleagues developed a hybrid approach combining elements of the RSVN-IAC and RLVN approaches to address the problems of postoperative headache and suboptimal eighth nerve exposure. They termed the novel technique combined retrosigmoid/retrolabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy.141 RRVN entails a limited mastoidectomy with removal of the bone covering the sigmoid sinus. The dura is then incised posterior to the sigmoid sinus, which is retracted forward. The surgeon next follows the posterior wall of the temporal bone toward cranial nerves IX to XI until the arachnoid layer near the jugular foramen is identified. Fenestration of this layer near cranial nerve IX releases the CSF in the area, which causes the cerebellum to fall away from the temporal bone and obviates the need for cerebellar retraction. The surgeon can then identify cranial nerve VIII in the cerebellopontine angle and proceed with selective vestibular neurectomy in a manner analogous to RLVN. However, if surgical exposure of cranial nerve VIII is suboptimal in the cerebellopontine angle, the surgeon has the option of making a small incision in the dura over the temporal bone as a prelude to drilling the internal auditory canal for transection of the superior vestibular nerve and avulsion of the posterior ampullary nerve, thereby effecting a complete vestibular neurectomy. RRVN also permits watertight closure of the dura.

In practice, RRVN appears to be safe and highly efficacious. A retrospective review of 210 cases by Goksu and coauthors reported complete resolution of vertigo in 90% of patients with Meniere’s disease, and an equal proportion of patients experienced no change or improved hearing postoperatively. Furthermore, the incidence of CSF leakage was less than 1%, and there were no documented cases of facial paresis.142 A review by Silverstein and Jackson revealed that postoperative headache and CSF leakage occurred at a negligible rate in RRVN patients—a significant improvement over RSVN and RLVN, respectively—and yielded similar results with respect to the cure rate for vertigo (85%) and preservation of preoperative hearing levels (80%).78

Endoscopically Assisted Vestibular Neurectomy

Endoscopic selective vestibular neurectomy is one of the latest additions to the surgical armamentarium for Meniere’s disease. Although endoscopic neurosurgery dates back to the early 1900s, use of the endoscope to treat intractable vertigo was developed in the 1990s, thus far with promising results. A case series by Miyazaki and colleagues involving 345 patients with medically refractory Meniere’s disease who underwent minimally invasive RSVN demonstrated complete or partial relief of vertigo in 96% of patients, with CSF leakage in 4%, and no documented cases of postoperative facial paresis or hearing loss.143 The Miyazaki series notwithstanding, there is a relative paucity of outcome data after endoscopic vestibular neurectomy for the treatment of refractory Meniere’s disease. Endoscopically assisted neurosurgery has several theoretical advantages over microscopic approaches to vestibular neurectomy, including better visualization of internal anatomic structures, less cerebellar retraction, and narrower surgical exposure, thereby reducing the risk for postoperative CSF leakage. However, there are depth perception issues associated with endoscopy that may compound the difficulty and danger of these operations. Furthermore, one runs the risk of thermal injury to delicate structures from endoscopic heating during the procedure.143,144

Badke MB, Pyle GM, Shea T, et al. Outcomes in vestibular ablative procedures. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:504.

Baloh RW. Prosper Meniere and his disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1151.

Bretlau P, Thomsen J, Tos M, et al. Placebo effect in surgery for Menière’s disease: nine-year follow-up. Am J Otol. 1989;10:259.

Catalano PJ, Jacobowitz O, Post KD. Prevention of headache after retrosigmoid removal of acoustic tumors. Am J Otol. 1996;17:904.

Chia SH, Gamst AC, Anderson JP, Harris JP. Intratympanic gentamicin therapy for Ménière’s disease: a meta-analysis. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:544.

Eisenman DJ, Speers R, Telian SA. Labyrinthectomy versus vestibular neurectomy: long-term physiologic and clinical outcomes. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:539.

Fukuhara T, Silverman DA, Hughes GB, et al. Vestibular nerve sectioning for intractable vertigo: efficacy of simplified retrosigmoid approach. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:67.

Furman J. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1590.

Gacek R. Singular neurectomy in the management of paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1994;27:363.

Glasscock ME3rd, Miller GW. Middle fossa vestibular nerve section in the management of Ménière’s disease. Laryngoscope. 1977;87:529.

Goksu N, Yilmaz M, Bayramoglu I, et al. Combined retrosigmoid retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: results of our experience over 10 years. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:481.

Green RE. Surgical treatment of vertigo, with follow-up on Walter Dandy’s cases: neurologic aspects. Clin Neurosurg. 1959:141.

Green RE, Douglass CC. Intracranial division of the eighth nerve for Meniere’s disease: a follow-up study of patients operated on by Dr. Walter Dandy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1951;60:610.

Hain TC, Yacovino D. Pharmacologic treatment of persons with dizziness. Neurol Clin. 2005;23:831.

Hilton M, Pinder DK. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;1:CD003162.

House JW, Hitselberger WE, McElveen J, et al. Retrolabyrinthine section of the vestibular nerve. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:212.

House WF. Surgical exposure of the internal auditory canal and its contents through the middle, cranial fossa. Laryngoscope. 1961;71:1363.

Jackler RK, Whimey D. A century of eighth nerve surgery. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:401.

Kemink JL, Hoff JT. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: analysis of results. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:33.

Kemink JL, Tellian SA, el-Kashlan H, et al. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: efficacy in disorders other than Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:523.

Leveque M, Labrousse M, Seidermann L, et al. Surgical therapy in intractable benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:693.

Levine SC, Glasscock M, McKennan KX. Long-term results of labyrinthectomy. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:125.

Miyazaki H, Deveze A, Magnan J. Neuro-otologic surgery through minimally invasive retrosigmoid approach: endoscope assisted microvascular decompression, vestibular neurotomy, and tumor removal. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1612.

Schuknecht HF. Ablation therapy for the relief of Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope. 1956;66:859.

Silverstein H, Jackson LE. Vestibular nerve section. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2002;35:655.

Silverstein H, Norrell H, Smouha E, et al. Combined retrolab-retrosigmoid vestibular neurectomy. An evolution in approach. Am J Otol. 1989;10:166.

1 Bauer CA. Otologic Symptoms and Syndromes. In Cummings CW, Haughey BH, et al, editors: Cummings Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 4th ed, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2005.

2 Davis LE. Comparative experimental viral labyrinthitis. Am J Otolaryngol. 1990;11:382.

3 Savitz SI, Caplan LR. Vertebrobasilar disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2618.

4 Taylor CL, Selman WR, Ratcheson RA. Steal affecting the central nervous system. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:679.

5 Dieterich M, Brandt T. Episodic vertigo related to migraine (90 cases): vestibular migraine? J Neurol. 1999;246:883.

6 Neuhauser H, Leopold M, von Brevern M, et al. The interrelations of migraine, vertigo, and migrainous vertigo. Neurology. 2001;56:436.

7 Lempert TT, Neuhauser HH. Migrainous vertigo. Neurol Clin. 2005;23:715.

8 Franco-Vidal VV, Négrevergne MM, Darrouzet VV. [Vertigo and pathology of the cerebello-pontine angle.]. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol. 2005;126:223.

9 Morrison GGA, Sterkers JJM. Unusual presentations of acoustic tumours. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1996;21:80.

10 Neff BA, Wilcox TOJr, Sataloff RT. Intralabyrinthine schwannomas. Otol Neurotol. 2003;24:299.

11 Baloh RW. Paraneoplastic cerebellar disorders. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;112:125.

12 Dalmau J, Gonzalez RG, Lerwill MF. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 4-2007. A 56-year-old woman with rapidly progressive vertigo and ataxia. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:612.

13 Gulya AJ. Neurologic paraneoplastic syndromes with neurotologic manifestations. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:754.

14 Alpini D, Caputo D, Pugnetti L, et al. Vertigo and multiple sclerosis: aspects of differential diagnosis. Neurol Sci. 2001;22(Suppl 2):S84.

15 Frohman EM, Zhang H, Dewey RB, et al. Vertigo in MS: utility of positional and particle repositioning maneuvers. Neurology. 2000;55:1566.

16 Bronstein AM. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: some recent advances. Curr Opin Neurol. 2003;16:1.

17 da Costa S. Meniere’s disease: overview, epidemiology, and natural history. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2002;35:455.

18 Furman J. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1590.

19 Kentala EE, Havia MM, Pyykkö II. Short-lasting drop attacks in Meniere’s disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;124:526.

20 von Brevern M, Radtke A, Lezius F, et al. Epidemiology of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo: a population-based study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:710.

21 Hilton M, Pinder DK. The Epley (canalith repositioning) manoeuvre for benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;1:CD003162.

22 Virre E, Purcell I, Baloh RW. The Dix-Hallpike test and the canalith repositioning maneuver. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:184.

23 Baloh RW. Prosper Meniere and his disease. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:1151.

24 Havia M, Kentala E, Pyykko I. Prevalence of Meniere’s disease in general population of Southern Finland. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;133:762.

25 Kotimäki J, Sorri M, Aantaa E, et al. Prevalence of Meniere disease in Finland. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:748.

26 Wladislavosky-Waserman P, Facer GW, Mokri B, et al. Meniere’s disease: a 30-year epidemiologic and clinical study in Rochester, Mn, 1951-1980. Laryngoscope. 1984;94:1098.

27 Davis LE, Johnsson L-G. Viral infections of the Inner Ear: Clinical, virologic, and pathologic studies in humans and animals. Am J Otolaryngol. 1983;4:347.

28 Olshaker JS. Dizziness and vertigo. In Marx J, editor: Rosen’s Emergency Medicine: Concepts and Clinical Practice, 6th ed, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2006.

29 Baloh RW. Clinical practice. Vestibular neuritis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1027.

30 Okinaka Y, Sekitani T, Okazaki H, et al. Progress of caloric response of vestibular neuronitis. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1993;503:18.

31 Friedland DR, Wackym PA. A critical appraisal of spontaneous perilymphatic fistulas of the inner ear. Am J Otol. 1999;20:261.

32 McCabe BF. Perilymph fistula: the Iowa experience to date. Am J Otol. 1989;10:262.

33 Seltzer S, McCabe BF. Perilymph fistula: the Iowa experience. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:37.

34 Fitzgerald DDC. Perilymphatic fistula and Meniere’s disease. Clinical series and literature review. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2001;110:430.

35 Minor LB, Cremer PD, Carey JP, et al. Symptoms and signs in superior canal dehiscence syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;942:259.

36 Stone JH, Francis HW. Immune-mediated inner ear disease. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12:32.

37 Gladwell M, Viozzi C. Temporal bone fractures: a review for the oral and maxillofacial surgeon. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008;66:513.

38 Eviatar L, Bergtraum M, Randel RM. Post-traumatic vertigo in children: a diagnostic approach. Pediatr Neurol. 1986;2:61.

39 Motin M, Keren O, Groswasser Z, et al. Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo as the cause of dizziness in patients after severe traumatic brain injury: diagnosis and treatment. Brain Inj. 2005;19:693.

40 Endo K, Ichimaru K, Komagata M, et al. Cervical vertigo and dizziness after whiplash injury. Eur Spine J. 2006;15:886.

41 Cooksey FS. Rehabilitation in vestibular injuries. Proc R Soc Med. 1946;39:273.

42 Cawthorne T. The physiological basis for head exercises. J Chartered Soc Physiother. 1944;30:106.

43 Wrisley D. Wrisley: Physical therapy for balance disorders. Neurol Clin. 2005;23:855.

44 Badke MB, Pyle GM, Shea T, et al. Outcomes in vestibular ablative procedures. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:504.

45 Black FO, Angel CR, Pesznecker SC, et al. Outcome analysis of individualized vestibular rehabilitation protocols. Am J Otol. 2000;21:543.

46 Brown KE, Whitney SL, Wrisley DM, et al. Physical therapy outcomes for persons with bilateral vestibular loss. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1812.

47 Cohen HS, Kamball KT. Increased independence and decreased vertigo after vestibular rehabilitation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:60.

48 Krebs DE, Gill-Body KM, Parker SW, et al. Vestibular rehabilitation: useful but not universally so. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:240.

49 Shepard NT, Telian SA. Vestibular and balance rehabilitation therapy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1993;102:198.

50 Suarez H, Arocena M, Suarez A, et al. Changes in postural control parameters after vestibular rehabilitation in patients with central vestibular disorders. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003;123:143.

51 Epley JJM. Human experience with canalith repositioning maneuvers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;942:179.

52 Epley JM. The canalith repositioning procedure: for treatment of benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;107:399.

53 Hain TC, Yacovino D. Pharmacologic treatment of persons with dizziness. Neurol Clin. 2005;23:831.

54 Martin J, Gilchrist JP, Smith PF, et al. Early diazepam treatment following unilateral labyrinthectomy does not impair vestibular compensation of spontaneous nystagmus in guinea pig. J Vestib Res. 1996;6:135.

55 Strupp M, Zingler VC, Arbusow V, et al. Methylprednisolone, valacyclovir, or the combination for vestibular neuritis. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:354.

56 Ariyasu L, Byl FM, Sprague MS, et al. The beneficial effect of methylprednisolone in acute vestibular vertigo. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116:700.

57 Morales-Luckie E, Cornejo-Suarez A, Zaragoza-Contreras MA, et al. Oral administration of prednisone to control refractory vertigo in Meniere’s disease: a pilot study. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:1022.

58 Jackson CG, Glasscock ME3rd, Davis WE, Hughes GB, Sismanis A. Medical management of Menière’s disease. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1981;90:142.

59 Klockhoff I, Lindblum U. Meniere’s disease and hydrochlorothiazide (Dichlotride)–a critical analysis of symptoms and therapeutic effects. Acta Otolaryngol. 1967;63:347.

60 van Deelen GW, Huizing EH. Use of a diuretic (Dyazide) in the treatment of Meniere’s disease. A double-blind cross-over placebo-controlled study. ORL J Otorhinollaryngol Relat Spec. 1986;48:287.

61 Maione A. Migraine-related vertigo: diagnostic criteria and prophylactic treatment. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:1782.

62 Leveque MM, Labrousse MM, Seidermann LL, et al. Surgical therapy in intractable benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136:693.

63 Gacek R. Singular neurectomy in the management of paroxysmal positional vertigo. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1994;27:363.

64 Parnes LS, McClure JA. Posterior semicircular canal occlusion in the normal hearing ear. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104:52.

65 Hawthorne M, el-Naggar M. Fenestration and occlusion of posterior semicircular canal for patients with intractable benign paroxysmal positional vertigo. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108:935.

66 Carey JP, Migliaccio AA, Minor LB. Semicircular canal function before and after surgery for superior canal dehiscence. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28:356.

67 Limb CJ, Carey JP, Srireddy S, et al. Auditory function in patients with surgically treated superior semicircular canal dehiscence. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27:969.

68 Black FO, Pesznecker S, Norton T, et al. Surgical management of perilymphatic fistulas: a Portland experience. Am J Otol. 1992;13:254.

69 Minor LB. Labyrinthine fistulae: pathobiology and management. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;11:340.

70 Rizer FM, House JW. Perilymph fistulas: the House Ear Clinic experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104:239.

71 Shelton C, Simmons FB. Perilymph fistula: the Stanford experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;97:105.

72 Meyerhoff WL. Spontaneous perilymphatic fistula: myth or fact. Am J Otol. 1993;13:478.

73 Beck C. Intratympanic application of gentamicin for treatment of Menière’s disease. Keio J Med. 1986;35:36.

74 Maitland GG. Perilymphatic fistula. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2001;1:486.

75 Toth AA, Parnes LS. Intratympanic gentamicin therapy for Menière’s disease: preliminary comparison of two regimens. J Otolaryngol. 1995;24:340.

76 Chia SH, Ganst AC, Anderson JP, et al. Intratympanic gentamicin therapy for Meniere’s disease: a meta-analysis. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:544.

77 Jackler RK, Whinney D. A century of eighth nerve surgery. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:401.

78 Silverstein H, Jackson LE. Vestibular nerve section. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2002;35:655.

79 Densert B, Densert O. Overpressure in treatment of Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope. 1982;92:1285.

80 Gates GA, Green JD, Tucci DL, et al. The effects of transtympanic micropressure treatment in people with unilateral Meniere’s disease. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2004;130:718.

81 Gates GA, Verrall A, Green JD, et al. Meniett clinical trial: long-term follow-up. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:1311.

82 Portmann G. The saccus endolymphaticus and an operation for draining the same for the relief of vertigo. 1927. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:1109.

83 Shambaugh GE. Effect of endolymphatic sac decompression on fluctuant hearing loss. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1975;8:537.

84 Shea JJ. Teflon film drainage of the endolymphatic sac. Arch Otolaryngol. 1966;83:316.

85 Welling DB, Nagaraja HN. Endolymphatic mastoid shunt: a reevaluation of efficacy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:340.

86 House WF. Subarachnoid shunt for the drainage of labyrinthine hydrops. Acta Otorinol Laringol Ibero-Americana. 1965;16:43.

87 Thomsen J, Bretlau P, Tos M, et al. Placebo effect in surgery for Ménière’s disease. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study on endolymphatic sac shunt surgery. Arch Otolaryngol. 1981;107:271.

88 Bretlau P, Thomsen J, Tos M, et al. Placebo effect in surgery for Menière’s disease: nine-year follow-up. Am J Otol. 1989;10:259.

89 Thomsen J, Bretlau P, Tos M, et al. Endolymphatic sac–mastoid shunt surgery. A nonspecific treatment modality? Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1986;95:32.

90 Silverstein HH, Smouha EE, Jones RR. Natural history vs. surgery for Menière’s disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;100:6.

91 Gates GA. Innovar treatment for Meniere’s disease. Acta Otolaryngol. 1999;119:189.

92 Benecke JE. Surgery for non-Meniere’s vertigo. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1994;513:37.

93 Kemink JL, Hoff JT. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: analysis of results. Laryngoscope. 1986;96:33.

94 Eisenman DJ, Speers R, Telian SA. Labyrinthectomy versus vestibular neurectomy: long-term physiologic and clinical outcomes. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:539.

95 Tewary AK, Riley N, Kerr AG. Long-term results of vestibular nerve section. J Laryngol Otol. 1998;112:1150.

96 Kemink JL, Graham MD. Hearing loss with delayed onset of vertigo. Am J Otol. 1985;6:344.

97 Shone G, Kemink JL, Telian SA. Prognostic significance of hearing loss as a lateralizing indicator in the surgical treatment of vertigo. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:618.

98 Katsarkas A, Segal BN. Unilateral loss of peripheral vestibular function in patients: degree of compensation and factors causing decompensation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;98:45.

99 Lake R. Removal of the semicircular canals in a case of unilateral aural vertigo. J Laryngol Rhinol Otol. 1904;19:350.

100 Milligan W. Meniere’s disease: a clinical and experimental inquiry. J Laryngol Otol. 1904;19:440.

101 Schuknecht HF. Ablation therapy for the relief of Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope. 1956;66:859.

102 Cawthorne T. The treatment of Meniere’s disease. J Laryngol Otol. 1943;58:363.

103 Schuknecht HF. Transcanal labyrinthectomy. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;2:17.

104 Graham MD, Colton JJ. Transmastoid labyrinthectomy indications. Technique and early postoperative results. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:1253.

105 Graham MD, Kemink JL. Transmastoid labyrinthectomy: surgical management of vertigo in the nonserviceable hearing ear. A five-year experience. Am J Otol. 1984;5:295.

106 Kemink L, Telian SA, Graham MD, et al. Transmastoid labyrinthectomy: reliable surgical management of vertigo. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;101:5.

107 Levine SC, Glasscock M, McKennan KX. Long-term results of labyrinthectomy. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:125.

108 Schwaber MK, Pensak ML, Reiber ME. Transmastoid labyrinthectomy in older patients. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:1152.

109 Perry RH. A case of tinnitus and vertigo treated by division of the auditory nerve. J Laryngol Otol. 1904;19:402.

110 Green RE, Douglass CC. Intracranial division of the eighth nerve for Meniere’s disease: a follow-up study of patients operated on by Dr. Walter Dandy. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1951;60:610.

111 McKenzie KG. Intracranial division of the vestibular portion of the auditory nerve for Meniere’s disease. Can Med Assoc J. 1936;34:369.

112 Green RE. Surgical treatment of vertigo, with follow-up on Walter Dandy’s cases: neurologic aspects. Clin Neurosurg. 1959:141.

113 Telian SA. Surgery for vestibular disorders. In Cummings CW, editor: Cummings Otolaryngology Head & Neck Surgery, 4th ed, Philadelphia: CV Mosby, 2005.

114 House WF. Surgical exposure of the internal auditory canal and its contents through the middle, cranial fossa. Laryngoscope. 1961;71:1363.

115 Fisch UU. Vestibular and cochlear neurectomy. Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1974;78:ORL252.

116 Glasscock ME3rd, Miller GW. Middle fossa vestibular nerve section in the management of Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope. 1977;87:529.

117 Garcia-Ibanez E, Garcia-Ibanez JL. Middle fossa vestibular neurectomy: a report of 373 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1980;88:486.

118 Kemink JL, Tellian SA, el-Kashlan H, Langman AW. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: efficacy in disorders other than Meniere’s disease. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:523.

119 McElveen JT, Shelton C, Hitselberger WE, et al. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy: a reevaluation. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:502.

120 Silverstein H, Norrell H. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1982;90:778.

121 Aristegui M, Canalis RF, Naguib M, et al. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: a current appraisal. Ear Nose Throat J. 1997;76:578.

122 Boyce SE, Mischke RE, Goin DW. Hearing results and control of vertigo after retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:257.

123 Glasscock ME, Thedinger BA, Cueva RA, et al. An analysis of the retrolabyrinthine vs. the retrosigmoid vestibular nerve section. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;104:88.

124 Monsell EM, Wiet RJ, Young NM, et al. Surgical treatment of vertigo with retrolabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:835.

125 Nguyen CD, Brackmann DE, Crane RT, et al. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: evaluation of technical modification in 143 cases. Am J Otol. 1992;13:328.

126 Ortiz Armenta A. Retrolabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy. 10 years’ experience. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol. 1992;113:413.

127 Teixido M, Wiet RJ. Hearing results in retrolabyrinthine vestibular neurectomy. Laryngoscope. 1992;102:33.

128 Zini C, Mazzoni A, Gandolfi A, et al. Retrolabyrinthine versus middle fossa vestibular neurectomy. Am J Otol. 1988;9:448.

129 House JW, Hitselberger WE, McElveen J, et al. Retrolabyrinthine section of the vestibular nerve. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:212.

130 Parikh AA, Brookes GB. Conductive hearing loss following retrolabyrinthine surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1996;122:841.

131 Silverstein H, Norrell H, Haberkamp T. A comparison of retrosigmoid IAC, retrolabyrinthine, and middle fossa vestibular neurectomy for treatment of vertigo. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:165.

132 Molony TB. Decision making in vestibular neurectomy. Am J Otol. 1996;17:421.

133 Pareschi R, Destito D, Falco Raucci A, et al. Posterior fossa vestibular neurotomy as primary surgical treatment of Menière’s disease: a re-evaluation. J Laryngol Otol. 2002;116:593.

134 McKenna MJ, Nadol JB, Ojemann RG, et al. Vestibular neurectomy: retrosigmoid-intracanalicular versus retrolabyrinthine approach. Am J Otol. 1996;17:253.

135 Silverman DA, Hughes GB, Kinney SE, et al. Technical modifications of suboccipital craniectomy for prevention of postoperative headache. Skull Base. 2004;14:77.

136 Silverstein H, Norrell H, Rosenberg S. The resurrection of vestibular neurectomy: a 10-year experience with 115 cases. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:533.

137 Fukuhara TT, Silverman DA, Hughes GB, et al. Vestibular nerve sectioning for intractable vertigo: efficacy of simplified retrosigmoid approach. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:67.

138 Catalano PJ, Jacobowitz O, Post KD. Prevention of headache after retrosigmoid removal of acoustic tumors. Am J Otol. 1996;17:904.

139 Lovely TJ, Lowry DW, Jannetta PJ. Functional outcome and the effect of cranioplasty after retromastoid craniectomy for microvascular decompression. Surg Neurol. 1999;51:191.

140 Silverstein H, Norrell H, Smouha EE. Retrosigmoid–internal auditory canal approach vs. retrolabyrinthine approach for vestibular neurectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;97:300.

141 Silverstein H, Norrell H, Smouha E, et al. Combined retrolab-retrosigmoid vestibular neurectomy. An evolution in approach. Am J Otol. 1989;10:166.

142 Goksu N, Yilmaz M, Bayramoglu I, et al. Combined retrosigmoid retrolabyrinthine vestibular nerve section: results of our experience over 10 years. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:481.

143 Miyazaki H, Deveze A, Magnan J. Neuro-otologic surgery through minimally invasive retrosigmoid approach: endoscope assisted microvascular decompression, vestibular neurotomy, and tumor removal. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1612.

144 Ozluoglu LN, Akbasak A. Video endoscopy–assisted vestibular neurectomy: a new approach to the eighth cranial nerve. Skull Base Surg. 1996;6:215.