Treatment of cancer-related pain

Medical therapy

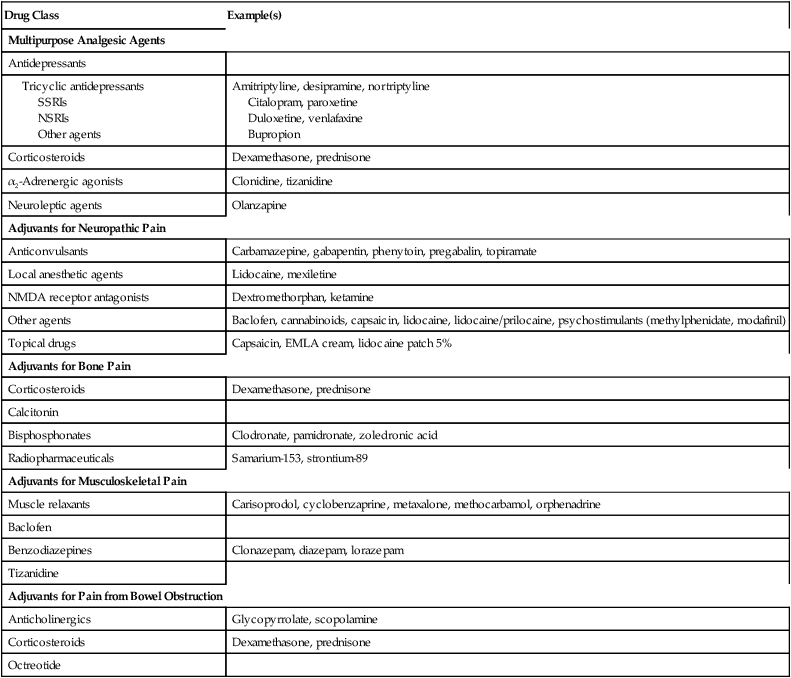

Adjuvant analgesic agents play a major role in treating patients with malignancies (Table 215-1). Most of these medications have a primary indication other than pain but have analgesic properties. The choice of adjuvant is made based on several assessments, including the type of pain, pharmacologic characteristics and adverse effects of the drug, interactions with other medications, and patient comorbid conditions (e.g., depression). Adjuvant agents comprise a diverse group of medications and can be broadly classified into multipurpose adjuvant analgesic agents and adjuvants specific for neuropathic pain, bone pain, musculoskeletal pain, and bowel obstruction.

Table 215-1

Adjuvant Analgesic Agents for the Treatment of Cancer-Related Pain: Major Classes

| Drug Class | Example(s) |

| Multipurpose Analgesic Agents | |

| Antidepressants | |

| Tricyclic antidepressants SSRIs NSRIs Other agents |

Amitriptyline, desipramine, nortriptyline Citalopram, paroxetine Duloxetine, venlafaxine Bupropion |

| Corticosteroids | Dexamethasone, prednisone |

| α2-Adrenergic agonists | Clonidine, tizanidine |

| Neuroleptic agents | Olanzapine |

| Adjuvants for Neuropathic Pain | |

| Anticonvulsants | Carbamazepine, gabapentin, phenytoin, pregabalin, topiramate |

| Local anesthetic agents | Lidocaine, mexiletine |

| NMDA receptor antagonists | Dextromethorphan, ketamine |

| Other agents | Baclofen, cannabinoids, capsaicin, lidocaine, lidocaine/prilocaine, psychostimulants (methylphenidate, modafinil) |

| Topical drugs | Capsaicin, EMLA cream, lidocaine patch 5% |

| Adjuvants for Bone Pain | |

| Corticosteroids | Dexamethasone, prednisone |

| Calcitonin | |

| Bisphosphonates | Clodronate, pamidronate, zoledronic acid |

| Radiopharmaceuticals | Samarium-153, strontium-89 |

| Adjuvants for Musculoskeletal Pain | |

| Muscle relaxants | Carisoprodol, cyclobenzaprine, metaxalone, methocarbamol, orphenadrine |

| Baclofen | |

| Benzodiazepines | Clonazepam, diazepam, lorazepam |

| Tizanidine | |

| Adjuvants for Pain from Bowel Obstruction | |

| Anticholinergics | Glycopyrrolate, scopolamine |

| Corticosteroids | Dexamethasone, prednisone |

| Octreotide |

Interventional therapy

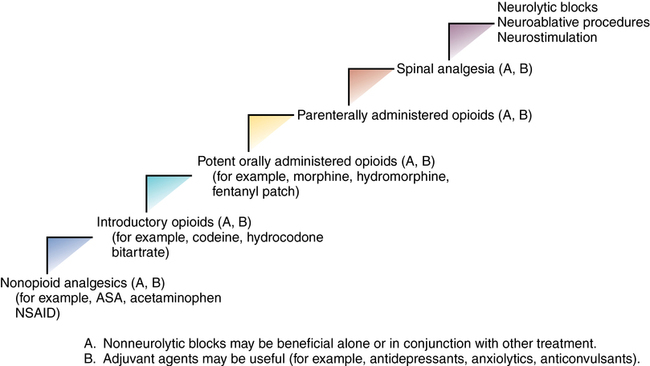

Given that the use of the World Health Organization’s analgesic ladder does not provide adequate analgesia for all patients with cancer, a revised stepwise approach has been developed that includes the use of interventional techniques (Figure 215-1).

Surgical procedures

As with all interventional techniques, these interventions are not without potential complications; therefore, the provider must carefully weigh the risks and benefits for each patient individually (Table 215-2).

Table 215-2

Potential Complications of Invasive Procedures for the Treatment of Cancer-Related Pain

| Treatment | Potential Adverse Effects |

| Neurolytic blocks | Sensorimotor impairment Sympathetic or parasympathetic impairment Postural hypotension Bowel or bladder dysfunction Pain recurrence Deafferentation pain Pneumothorax* |

| Spinally administered opioids | Respiratory depression Pruritus Urinary retention Nausea and vomiting |

| Spinally administered clonidine | Hypotension Sedation |

| Spinally administered local anesthetic agent | Sympathetic blockade† Exaggerated spread‡ Motor block |

| Neurosurgical procedures | Bladder dysfunction Motor weakness Deafferentation pain Respiratory dysfunction§ |

| Neuraxial catheters | Catheter break or leak Catheter obstruction Infection¶ CSF leak |

| Spinally administered ziconotide | Psychiatric symptoms# Motor deficits Meningitis Seizures |

†Hypotension, urinary retention.

¶Cellulitis, epidural abscess, meningitis.

#Hallucinations, new or worsening depression, suicidal ideation.