chapter 45 Travel medicine

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

There has been an increasing trend for people to travel internationally.1 Ease of air transportation has ensured that nearly 1 billion people travel internationally each year to every part of the globe.2 These travellers are potentially exposed to infectious diseases for which they have no immunity, as well as other serious threats to wellbeing, such as accidents and exacerbation of pre-existing medical and dental conditions. Conservatively, it is estimated that 30–50% of travellers become ill or are injured while travelling.3,4 Relative estimated monthly incidence rates of various health problems have been compiled elsewhere.3 The risk of severe injury is thought to be greater for people when travelling abroad.1,5

In terms of morbidity, infectious diseases such as respiratory tract infection and traveller’s diarrhoea, and injuries, are important concerns for travellers.1,4,5 The main health complaints of returned travellers vary considerably, depending on the country visited and the duration of the visit. Some studies have reported, based on travel insurance claims, that respiratory, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, ear, nose and throat, and dental conditions were the most common presenting problems,6 whereas others have found that infectious disease (43.5%), accidents involving the extremities (15.3%), psychiatric conditions (8.2%), pulmonary disorders (4.7%) and accidents involving the head (4.7%) were the most common.3,7 Fortunately, few travellers die abroad, and those who do tend to die of pre-existing conditions, such as myocardial infarction in travellers with known ischaemic heart disease. However, accidents are also a major cause of travel-related mortality.8 This chapter highlights some of the current issues in travel medicine, but excludes specific discussion concerning migrant health.

DEFINING TRAVEL MEDICINE

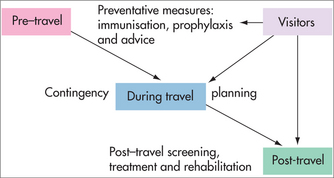

The roles of the GP or travel health adviser in the provision of travel health advice can be regarded as a continuum (Fig 45.1) and include:

PRE-TRAVEL HEALTH CONSULTATION

The pre-travel health consultation involves consideration of and advice about various aspects of travel-related health, including fitness to travel and the health risks of travelling in itself, including exposure to infectious diseases and diseases arising from travel. This may necessitate the provision of malaria and other chemoprophylaxis, and various vaccinations. The areas that may be covered in the pre-travel health consultation with travellers are listed in Table 45.1.

TABLE 45.1 Areas that might be covered in pre-travel preparation of patients going aboard

| Advise/discuss | |

| Insects | Repellents, nets, permethrin |

| Ingestions | Care with food and water |

| Infections | Skin, environment |

| Indiscretions | STIs, HIV |

| Injuries | Accident avoidance, safety |

| Immersion | Schistosomiasis |

| Insurance | Health and travel insurance |

| Finding medical assistance abroad | |

| First aid advice | |

| Vaccinate | |

| Always | National immunisation schedule vaccines |

| Often | Hepatitis A, influenza |

| Sometimes | Typhoid |

| Japanese encephalitis | |

| Meningococcal disease | |

| Polio | |

| Rabies | |

| Tetanus–diphtheria | |

| Yellow fever | |

| Older travellers | Pneumococcus |

| Influenza | |

| Pandemic influenza, e.g. pandemic (H1N1) 2009 | |

| Prescribe | |

| Always | Regular medication |

| Sometimes | Antimalarial medication |

| Diarrhoeal self-treatment | |

| Condoms | |

| Traveller’s medical kit | |

Source: modified from Seelan & Leggat 200310 and Ingram & Ellis-Pegler 199611

This information may be obtained by a standardised questionnaire, which may be developed in the context of a travel clinic network or general practice network, or by individual travel health advisers. The World Health Organization (WHO) has provided an example of the types of questions to be asked in international travel and health.12 Practice or clinic staff can assist by ensuring that this information is obtained before the formal consultation. It is important that the procedure is time efficient for a practice, to improve flow and time management.

In the general practice setting, detailed records may be available to assist in assessing the traveller’s medical risks for travel. In any event, these records may need updating if the traveller has not presented to the GP for some time. Travel clinics, general practices and those in the travel industry should make it clear to prospective travellers that they should present early before travel, to obtain their travel medicine advice, immunisations and chemoprophylaxis or be referred for specialist advice, such as a pre-travel dental check. This may be best stated in a formal practice policy, so that travellers are aware of these possible requirements, which might be advertised in clinic newsletters, websites or practice updates or reminders.

ESTABLISHING THE RISKS

The risks of travel that need to be assessed for most travellers include the risks of the:

The risks of the destination and any specific requirements for travel health advice may be obtained from a variety of resources. The WHO publishes a booklet entitled International Travel and Health.12 Several other publications and sources of information relevant to travel medicine are also available. Online computerised databases have long since been mooted as useful aids for providing the most up-to-date and validated information for advising on travel medicine.13

POST-TRAVEL CONSULTATION

The traveller should also be advised of the possible need for follow-up and management after travel, particularly if going to a high-risk area (e.g. for malaria) or if they have any illness upon return (e.g. fever; persistent or bloody, mucous diarrhoea).14 It must be impressed upon the traveller that, in the event of any illness upon return, they should inform the treating physician of their recent travel and that they have travelled, for example, to a malaria area. It is important, if seeing a traveller with a post-travel health problem, that a risk assessment similar to the pre-travel health consultation is undertaken, guided by the presenting features of the illness or injury against a background of the patient’s general health. Even travellers who have been seen in the clinic or general practice for pre-travel health advice may need to have the risk assessment re-evaluated if any of the parameters of risk have changed (e.g. the person has travelled to a new destination). The risks of travel may also be modified by:

DEVELOPMENTS IN TRAVEL MEDICINE

Several key developments in the past two decades have ensured the continuing emergence of travel medicine as a specialty area. The development of national programs and guidelines in travel health was an important advance, as this recognised the need to develop a consensus strategy for combating commonly encountered infectious diseases and other problems encountered by travellers. Examples of these include the former Australian Government’s Travel Safe® Programme, including the publication of Australian guidelines for travel health,15 and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) travel health program.16 These programs and guidelines were directed at the major providers of travel health advice, such as general practices and public health agencies, but also travel clinics and travel agents. Internationally, the World Health Organization has also been producing travel health guidelines. (Examples of major travel health guidelines can be found in the Resources list.)

Three main challenges confront effective travel medicine practice.

Many of these challenges can be at least partially addressed through industry and government cooperation, particularly at the level of the travel agent or airline, which have initial contact with travellers. Many countries now have foreign travel advisory services that help keep practitioners advised about things such as important travel warnings and global disease outbreaks.

One of the most important factors influencing whether travellers seek health advice is the perceived risk and severity of tropical diseases,1 despite their relatively low health and safety risk to travellers compared with accidents and less exotic conditions such as traveller’s diarrhoea. In addition to the prevention of potentially lethal diseases and injuries among travellers abroad, the importance of providing travel health services is also increasingly being recognised in relation to early detection and reporting of imported infections.

PROFESSIONAL INITIATIVES

The International Society of Travel Medicine (ISTM), established in 1991, has taken the lead in establishing a global professional base for travel medicine. Some of the important early initiatives of the ISTM were the provision of travel health alerts to subscribers, a journal, biennial conferences, a global listing of travel health practitioners, and a collaborative disease-reporting network (GeoSentinel) with the CDC in the United States.18 GeoSentinel has played a role regionally in examining post-travel health problems.19 More recently, the ISTM has developed a certification program based on a detailed body of knowledge in travel medicine leading to a Certificate of Travel Health.20 GeoSentinel is an excellent example of the contribution of travel medicine to the early detection and reporting of imported infections, to which several sites in Australia and New Zealand contribute.21

The Asia Pacific Travel Health Association also conducts biennial conferences in travel medicine in the Asia-Pacific region, in alternate years to the ISTM’s annual conference and in parallel with its endorsed regional conference. The two major journals in travel medicine are currently the ISTM’s Journal of Travel Medicine, published by Wiley-Blackwell, and Travel Medicine and Infectious Diseases, published by Elsevier Science. In Australia, the development of a professional body in travel medicine, the first Faculty of Travel Medicine (FTM), has been achieved22 as part of the Australasian College of Tropical Medicine (ACTM). The FTM works in close association with the New Zealand Society of Travel Medicine, established in 1997. The ACTM produces the Annals of the ACTM, which is subtitled ‘A journal of tropical and travel medicine’, reflecting the major interests of the college and its faculty. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow subsequently founded an FTM in 2006.

VECTOR-BORNE DISEASES

Vector-borne diseases remain among the great personal concerns for travellers abroad, especially those travelling to more remote tropical areas. Some vector-borne diseases also represent a potential public health problem when returning home. Malaria remains the single most important vector-borne disease problem, although arboviral diseases such as dengue and Japanese encephalitis (JE) are also becoming increasingly important international travel-related health problems. Some vector-borne diseases are important for local travel within a country or region—an example is scrub typhus, which has affected soldiers in northern Queensland, Australia.23,24

Personal protective measures remain the first line of defence for vector-borne diseases. Travellers need to be aware of when the vectors bite and the seasonal nature of some of these vectors. Table 45.2 summarises the biting behaviour of mosquitoes that carry major diseases. Other vectors also have peak biting times between dusk and dawn (e.g. phlebotomine sandflies transmitting leishmaniasis). Preventive measures are mostly directed at reducing contact with vectors, such as: staying in screened or air-conditioned accommodation where possible; spraying the accommodation area; using permethrin-impregnated clothing to cover as much of the body as possible; using diethyl methyl toluamide (or DEET) repellents; controlling vermin and stray animals; and using bed nets soaked in permethrin, and fine-mesh bed nets to prevent sandfly bites. Currently available non-DEET repellents do not provide protection for durations similar to those of DEET-based repellents.25 For example, a number of citronella products have been tested, but these give very short-term protection.25 Soybean oil (2%) provides some protection, but again of much shorter duration than DEET-based products.25 More recently, 20% Citrodiol®, a lemon-eucalyptus extract, has been found to be as effective as DEET in preventing mosquito and other insect bites and provides about 7–8 hours protection.26

TABLE 45.2 Time of peak biting activity of mosquito genus by disease

| Mosquito genus | Peak times of activity | Examples of diseases transmitted |

|---|---|---|

| Anopheles | Usually night (‘dusk to dawn’), mainly rural | Malaria, lymphatic filariasis |

| Culex | Usually evening/night (‘dusk to dawn’) | Japanese encephalitis, West Nile virus, lymphatic filariasis |

| Aedes | Usually day biting, midday | Dengue, yellow fever, lymphatic filariasis |

| Mansonia | Usually night | Lymphatic filariasis |

MALARIA

Malaria is a serious disease caused by a protozoan parasite largely confined to the tropics. The WHO estimates that there are more than 500 million cases of malaria infection and 2.5 million deaths due to malaria worldwide annually.27 Most cases and deaths occur due to infection with Plasmodium falciparum species of malaria, although infection due to P. vivax also remains important, especially as dormant liver stages of the life cycle can cause relapses, sometimes several, for months after returning home. While Australia is malaria-free, suitable vectors of the Anopheles mosquito can be found in many parts of tropical northern Australia, resulting in occasional reports of local transmission from imported cases of malaria.28,29

The growing incidence of chloroquine and multiple drug resistance in P. falciparum and, more recently, P. vivax have limited the antimalarial drug options for malaria chemoprophylaxis. Current recommended malaria chemoprophylaxis options include doxycycline (one 100 mg tablet daily), mefloquine (one tablet weekly), and atovaquone plus proguanil or Malarone® (one tablet daily, consisting of 250 mg of atovaquone and 100 mg of proguanil).16 Chloroquine continues to be recommended as malaria chemoprophylaxis for malaria in the few areas where there is no chloroquine resistance.

Malaria eradication

Current eradication treatment for malaria is primaquine (two 7.5 mg tablets twice daily for 2 weeks), although tafenoquine was trialled in defence force personnel in East Timor as both an alternative eradication treatment (400 mg daily for 3 days) and a weekly-dose chemoprophylactic agent.30

Because of the incidence of neuropsychiatric side effects, such as anxiety and nightmares, it is advisable for travellers taking mefloquine for the first time to take several trial doses, possibly commencing as early as 3 weeks before departure.31 It is also advisable that travellers are given trial doses of other antimalarials, such as doxycycline and Malarone®, that they might be taking for the first time well before departure. This is to ensure that there is time to consider alternative chemoprophylactic drugs.31 If travel is commenced at short notice, modification to antimalarial regimens may have to be done abroad, which is less satisfactory. There are varying opinions on how long antimalarial drugs should continue to be taken after leaving an antimalarial area. However, antimalarial drugs that have no pre-erythrocytic effects on the liver stages of the malarial parasite, such as doxycycline and mefloquine, should be continued for up to 4 weeks afterwards. This relates to the time it takes for parasites to develop in the liver and infect the bloodstream. Chemoprophylaxis with Malarone®, which also has some effects on the hepatic stages of P. falciparum parasites, may be able to be given for shorter periods (e.g. one week) after return.32

For travellers to more remote areas, standby treatment in the event of overt malaria infection while abroad may also be useful. ‘Standby treatment consists of a course of antimalarial drugs that travellers to malaria endemic areas can use for self-treatment if they are unable to gain access to medical advice within 24 hours of becoming unwell.’31a In these situations, a traveller’s medical kit may be supplied with a thermometer, possibly an immunochromatographic test (ICT) malaria diagnostic kit and written instructions, and an appropriate malaria treatment course and written instructions, and the traveller must seek medical advice as soon as possible. Newer antimalarials that may be useful for standby treatment include Malarone® and Riamet®, the latter containing 20 mg artemether and 120 mg lumefantrine.33

ARBOVIRAL DISEASES

There are many arboviral diseases that may affect travellers. Apart from yellow fever, which has a widespread distribution in many parts of South America and Africa and is controlled by international health regulations,34 two of the most important arboviral diseases for travellers are dengue fever and Japanese encephalitis, because in recent years people have been travelling to more remote areas where these diseases are endemic. Both diseases are transmitted by various species of mosquitoes.

Dengue fever is a major global public health problem. The WHO estimates that there are more than 50 million cases per year.34 Dengue is a viral illness transmitted by Aedes mosquito species, classically Aedes aegypti. Infection may range from subclinical to fever, arthralgia and rash, or be complicated by haemorrhagic diatheses or shock syndromes. Treatment is supportive, while management of the problem is directed towards early detection of the disease and preventing transmission upon return to receptive countries.35 Numerous outbreaks of dengue have been attributed to travellers returning with the disease, associated with delays in detecting the condition.35 With travellers arriving or returning from abroad during the incubation period of the disease, it is vital that there is a collaborative effort made by various civilian public health authorities to contain and prevent the transmission of the disease among the local population.36 Until a vaccination becomes available, the mainstays of dengue prevention are personal protective measures and environmental health measures against disease vectors.35

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is the leading cause of viral encephalitis in Asia. The WHO estimates that there are more than 70,000 cases annually in South-East Asia.37 Up to a third of clinical cases die and about half of clinical cases of JE have permanent residual neurological sequelae.37 Despite the availability of a vaccine against JE, the immunogenicity of these vaccines has recently been questioned and concerns have been raised regarding adverse reactions reported with vaccination.38 The current development of safer and more immunogenic second-generation JE vaccines will be important for travellers in this region in the future.37

PREVENTION OF INFECTIOUS DISEASES THROUGH VACCINATION

A number of infectious diseases of travellers can be prevented by immunisation. There are few mandatory vaccines, for which certification is necessary, and these include yellow fever and meningococcal meningitis. Yellow fever vaccination is required for all travellers entering or returning from a yellow fever endemic area, which is prescribed by the WHO.27,39 Meningococcal vaccination is required for travellers to Mecca.27

The travel medicine consultation is also an opportunity to update routine and national schedule vaccinations for diseases that may afflict travellers anywhere. There are also a variety of vaccinations that may be required for travellers to particular destinations. It would seem prudent to vaccinate travellers against diseases that might be acquired through food and water, such as hepatitis A, typhoid and polio,31 as well as using other measures to combat these diseases. The most common vaccine-preventable diseases of travellers are hepatitis A and influenza3; however, typhoid vaccination should also be considered for travel to many developing countries. Polio vaccination is rarely required these days, with a concerted campaign for global eradication; however, it may be required in situations where polio outbreaks have been reported.31

There are a number of other infectious diseases, such as hepatitis B, JE and rabies, that may afflict travellers to certain destinations or are a result of the nature of their travel and are vaccine preventable (see Table 45.1).

For older travellers, pneumococcal and influenza vaccinations should also be considered. The development of combination vaccines, such as hepatitis A plus typhoid and hepatitis A plus B, has greatly reduced the number of injections required.31 The development of rapid schedules for travellers departing at short notice has been useful in providing protection within 4 weeks.31 Many diseases have no vaccination. For example, some parasitic diseases, such as intestinal and filarial helminths, can only be prevented through personal protective measures against the infective stages of the parasite and/or through periodic treatment or eradication treatment on return.

TRAVELLER’S DIARRHOEA

Traveller’s diarrhoea (see Ch 30, Gastroenterology) is a common problem for travellers and emphasises the importance of being able to communicate basic public health advice to the individual. It also highlights the need for a sound knowledge of tropical diseases. In general, reference may need to be made to:

A recent meta-analysis suggested that several probiotics have significant efficacy in preventing traveller’s diarrhoea, in particular Saccharomyces boulardii and a mixture of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum.40

NON-INFECTIOUS HAZARDS OF TRAVEL

Despite the emphasis on infectious disease in travel medicine, the single most common preventable cause of death among travellers is accidental injury.8,41

The patterns of mortality among travellers from the United States, Switzerland, Canada and Australia are similar. This is illustrated by research indicating that about 35% of deaths of Australian travellers abroad were the result of ischaemic heart disease, with natural causes overall accounting for some 50% of deaths.8 Trauma accounted for 25% of deaths abroad.8 Injuries were the reported cause of 18% of all deaths, with the major group being motor vehicle accidents, accounting for 7% of all deaths, which appeared to be over-represented in developing countries.8 Infectious disease was reported as the cause of death in only 2.4% of those who died while travelling abroad.8

A similar pattern of mortality was observed in Swiss,41 American42 and Canadian43 travellers abroad. Deaths of travellers have also resulted from air crashes, drowning, boating accidents, skiing accidents, bombs and electrocution.8 Homicides, suicides and executions combined accounted for about 8% of all deaths.8 Most fatal accidents in American and Swiss travellers were traffic or swimming accidents.41,42 Deaths of tourists visiting Australia were similarly found to be due mainly to motor vehicle accidents and accidental drowning.44

ISSUES IN AVIATION MEDICINE AND ALTITUDE

Travel medicine is also a key component of the activities of many healthcare professionals working in aviation medicine. In addition to undertaking aviation medical examinations and advising their own staff who are travelling, airline medical departments review passengers’ clearances to fly and provide advice to travel health advisers. Some travellers need special clearance to fly in cases of aeromedical evacuation (AME) on commercial aircraft and in certain prescribed circumstances of normal travel, such as after recent surgery or with serious physical or mental incapacity,45 and liaison by travel health advisers with the airline medical departments is usually advisable. Healthcare professionals working in aviation medicine also become involved in developing policies and guidelines for dealing with in-flight emergencies involving travellers as well as training in first aid for flight attendants. Physicians working in aviation medicine have their own national or regional professional organisations.

While some medical practitioners undertake the work of Designated Aviation Medical Examiners,46 particularly in respect of pilots, air traffic controllers and, in some instances, flight attendants, travel health advisers also need to be aware of the potential health effects of modern airline travel. These include the effects of reduced atmospheric pressure, low humidity, closed environment, inactivity, the effects of crossing several time zones on circadian rhythm, alcohol, and the general effects of aircraft motion and movement.47 These effects can produce conditions such as barotrauma, dehydration, jet lag, motion sickness, claustrophobia and panic attacks, air rage and spread of infectious disease, and can contribute to the development of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) and venous thromboembolism (VTE).47 Concerns have also been raised about the transmission of tuberculosis through close proximity to infected travellers on commercial aircraft.48 The provision of travel health advice and preventive measures for these conditions also largely falls to the travel medicine provider.

While considerable attention has been focused on DVT and VTE, it remains uncertain what the contribution of air travel is to the development of this condition among travellers. What seems to be clear is that the development of DVT and VTE is multifactorial.49 While the identification of travellers with predisposing risk factors would seem useful, it is only an option where the risks of side effects of the screening procedure do not outweigh the risks of developing DVT after a long-haul flight, which is estimated to be about 1 in 200,000 for travellers on a 12-hour long haul journey.50 In the meantime, conservative measures should be recommended, such as in-flight exercises, restriction of alcoholic and caffeinated beverages and drinking lots of water. Other preventive measures for some at-risk cases, such as subcutaneous heparin, are worthy of investigation.31 Current epidemiological research and pathophysiological studies are helping to establish which travellers are at greatest risk, which will in turn lead to appropriate intervention studies.

One of the most interesting problems in travel medicine has been the prevention of altitude illness. It has been difficult to find associations that might be useful in screening for individuals at higher risk; hence the focus has been on early treatment or the use of prophylactic agents such as acetazolamide. Natural compounds have been explored and Ginkgo biloba has been widely used; however, a recent trial suggested that Ginkgo biloba performed very poorly compared with drugs such as azetazolamide.51 Further studies are probably needed in human populations at risk.

TRAVEL ADVISORIES

In recent times, travel advisories have assumed great importance in endeavouring to ensure the safety and security of travellers. Travel advisory services include the US State Department,52 the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade,53 and the UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office.54 Travellers have suffered numerous casualties from recent acts of terrorism, most notably the Bali bombings, and natural disasters, most notably the Asian tsunami, both of which required a rapid multiagency response to rescue travellers from the affected areas.55–57

TRAVEL INSURANCE

Because of the potentially high costs of medical and dental treatment abroad, which may not be covered by private health insurance or local national health services, and the potential high costs associated with AME, all travellers should be advised of the need for comprehensive travel insurance. Travel insurance policies normally underwrite travel-related, medical and dental expenses incurred by travellers abroad under conditions specified by the travel insurance policy. In addition, travel insurance companies often provide a direct service, usually through their emergency assistance service contractors, to assist travellers abroad. This may include assistance with accessing or obtaining medical care while overseas, including AME. For example, claims for reimbursement of medical and dental expenses abroad made up more than two-thirds of all travel insurance claims in Australia and Switzerland.6,7 In the Australian study, almost one in five Australian travellers abroad had been found to have used the travel insurer’s emergency assistance service.6

Travel insurance is the most important safety net for travellers in the event of illness, injury or unforeseen events, and should be reinforced by GPs and travel health advisers. Studies have shown that about 60% of GPs in New Zealand,58 39% of GPs in Australia10 and 39% of travel clinics worldwide59 usually advise travellers about travel insurance. Although the majority of GPs also usually advise travellers about ways to find medical assistance abroad,58 GPs need to ensure that they provide advice on suitable travel insurance companies, especially as a source of medical assistance while travelling. However, it is not known what proportion of travel agents or airlines currently give advice on travel insurance routinely, although most airlines operating internationally now provide more travel health advice in their in-flight magazines.60

Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. http://www.dfat.gov.au.

Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada, Travel Health. http://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/tmp-pmv/.

CDC, Health Information for International Travel. http://wwwn.cdc.gov/travel/default.aspx.

CDC, Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr.

CIA World Factbook. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/.

Faculty of Travel Medicine/New Zealand Society of Travel Medicine, Australasian College of Tropical Medicine. http://www.tropmed.org/travel/index.html.

Faculty of Travel Medicine, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow. http://www.rcpsg.ac.uk/Travel%20Medicine/.

James Cook University, Travel Medicine Program. http://www.jcu.edu.au.

International Association for Medical Assistance to Travellers. http://www.iamat.org.

International Society of Travel Medicine. http://www.istm.org.

South African Society of Travel Medicine, Travel medicine Program. http://www.sastm.org.za/.

UK Fit for Travel. http://www.fitfortravel.nhs.uk/home.aspx.

UK Foreign and Commonwealth Office. http://www.fco.gov.uk/en/.

University of Otago, Travel medicine program. http://www.otago.ac.nz.

US Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs. http://travel.state.gov/.

WHO, International Travel and Health. http://www.who.int/ith/index.html.

WHO, Weekly Epidemiological Record. http://www.who.int/wer.

Worldwise Travellers Health Centres of New Zealand. http://www.worldwise.co.nz.

1 Behrens RH. Protecting the health of the international traveller. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1990;84:611-612. 629

2 World Tourism Organisation. Online. Available: http://www.unwto.org/index.php, 5 December 2007.

3 Steffen R, de Bernardis C, Banos A. Travel epidemiology—a global perspective. Int J Antimicrobiol Agents. 2003;21:89-95.

4 Cossar JH, Reid D, Fallon RJ, et al. A cumulative review of studies on travellers, their experience of illness and the implications of these findings. J Infect. 1990;21:27-42.

5 Bewes PC. Trauma and accidents: practical aspects of the prevention and management of trauma associated with travel. Br Med Bull. 1993;49:454-464.

6 Leggat PA, Leggat FW. Travel insurance claims made by travelers from Australia. J Travel Med. 2002;9:59-65.

7 Somer Kniestedt RA, Steffen R. Travel health insurance: indicator of serious travel health risks. J Travel Med. 2003;10:185-189.

8 Prociv P. Deaths of Australian travellers overseas. Med J Aust. 1995;163:27-30.

9 Leggat PA, Ross MH, Goldsmid JM. Introduction to travel medicine (Ch 1). In: Leggat PA, Goldsmid JM, editors. Primer of travel medicine. 3rd rev edn. Brisbane: ACTM; 2005:3-21. a p 3.

10 Seelan ST, Leggat PA. Health advice given by general practitioners for travellers from Australia. Travel Med Inf Dis. 2003;1:47-52.

11 Ingram RJH, Ellis-Pegler RB. What’s new in travel medicine? NZ Public Health Rep. 1996;3(8):57-59.

12 World Health Organization. International travel and health. Geneva: WHO; 2007. Online. Available: http://www.who.int/ith, 5 December 2007.

13 Cossar JH, Walker E, Reid D, et al. Computerised advice on malaria prevention and immunisation. BMJ. 1988;296:358.

14 Looke DFM, Robson JMB. Infections in the returned traveller. Med J Aust. 2002;177:212-219.

15 Commonwealth Department of Health. Health information for international travel; 4th edn. Canberra: AGPS, 1995.

16 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health information for international travel 2009–2010. Online. Available: http://wwwn.cdc.gov/travel/default.aspx, 25 March 2010.

17 Wilder-Smith A, Khairullah NS, Song JH, et al. Travel health knowledge, attitudes and practices among Australasian travelers. J Travel Med. 2004;11:9-15.

18 Freedman DO, Kozarsky PE, Weld LH, et al. GeoSentinel: The Global Emerging Infections Sentinel network of the International Society of Travel Medicine. J Travel Med. 1999;6:94-98.

19 International Society of Travel Medicine. GeoSentinel. Online. Available: http://www.istm.org, 5 December 2007.

20 Kozarsky PE, Keystone JS. Body of knowledge for the practice of travel medicine. J Travel Med. 2002;9:112-115.

21 Shaw MTM, Leggat PA, Weld LH, et al. Illness in returned travellers presenting at GeoSentinel sites in New Zealand. Aust NZ J Pub Health. 2003;27:82-86.

22 Leggat PA, Klein M. The Australasian Faculty of Travel Medicine. Travel Med Inf Dis. 2004;2:47-49.

23 McBride WJH, Taylor CT, Pryor JA, et al. Scrub typhus in north Queensland. Med J Aust. 1999;170:318-320.

24 Likeman RK. Scrub typhus: a recent outbreak among military personnel in North Queensland. ADF Health. 2006;7:10-13.

25 Fradin MS, Day JF. Comparative efficacy of insect repellents against mosquito bites. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:13-18.

26 Centers for Disease Control (CDC). Updated information regarding insect repellents. Online. Available: http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/dvbid/westnile/RepellentUpdates.htm, 5 May 2010.

27 World Health Organization. Malaria. Fact sheet. Updated April 2010. Online. Available: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs094/en/, 5 May 2010.

28 Hanna JN, Ritchie SA, Eisen DP, et al. An outbreak of Plasmodium vivax malaria in Far North Queensland, 2002. Med J Aust. 2004;180:24-28.

29 Brookes DL, Ritchie SA, van den Hurk AF, et al. Plasmodium vivax malaria acquired in far north Queensland. Med J Aust. 1997;166:82-83.

30 Edstein MD, Nasveld PE, Rieckmann KH. The challenge of effective chemoprophylaxis against malaria. ADF Health. 2001;2:12-16.

31 Zuckerman JN. Recent developments: travel medicine. BMJ. 2002;325:260-264. a p 262.

32 Looareesuwan S, Chulay JD, Canfield CJ, et al. Malarone (atovaquone and proguanil hydrochloride): a review of its clinical development for treatment of malaria. Malarone Clinical Trials Study Group. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60:533-541.

33 Omari AA, Preston C, Garner P. Artemether-lumefantrine for treating uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD003125.

34 World Health Organization. Dengue and dengue haemorrhagic fever. Fact sheet no. 117. Online. Available: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs117/en/, March 2009. 5 May 2010.

35 Malcolm RL, Hanna JN, Phillips DA. The timeliness of notification of clinically suspected cases of dengue imported into north Queensland. Aust NZ J Pub Health. 1999;23:414-417.

36 Kitchener S, Leggat PA, Brennan L, et al. The importation of dengue by soldiers returning from East Timor to north Queensland, Australia. J Travel Med. 2002;9:180-183.

37 Kitchener S. Most recent developments in Japanese encephalitis vaccines. Aust Mil Med. 2002;11:88-92.

38 Kurane I, Takasaki T. Immunogenicity and protective efficacy of the current inactivated Japanese encephalitis vaccine against different Japanese encephalitis virus strains. Vaccine. 2000;18(Suppl 2):33-35.

39 World Health Organization. International health regulations. Geneva: WHO; 2005. Online. Available: http://www.who.int/ihr/en/, 5 May 2010.

40 McFarland LV. Meta-analysis of probiotics for the prevention of traveler’s diarrhea. Travel Med Inf Dis. 2007;5:97-105.

41 Steffen R. Travel medicine: prevention based on epidemiological data. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85:156-162.

42 Baker TD, Hargarten SW, Guptill KS. The uncounted dead—American civilians dying overseas. Pub Health Rep. 1992;107:155-159.

43 MacPherson DW, Gushulak BD, Sandhu J. Death and international travel: the Canadian experience 1996 to 2004. J Travel Med. 2007;14:77-84.

44 Leggat PA, Wilks J. Overseas visitor deaths in Australia, 2001 to 2003. J Travel Med. 2009;16:243-247.

45 Cheng I. Screening of passenger fitness to fly and medical kits on board commercial aircraft. J Aust Soc Ae Space Med. 2009;4:14-18.

46 Civil Aviation Safety Authority. Designated aviation medical examiner handbook. Rev November 2008. Online. Available: http://www.casa.gov.au/scripts/nc.dll?WCMS:STANDARD:1001:pc=PC_91302, 5 May 2010.

47 Graham H, Putland J, Leggat P. Air travel for people with special needs (Ch 8). In: Leggat PA, Goldsmid JM, editors. Primer of travel medicine. 3rd rev ed. Brisbane: ACTM; 2005:100-112.

48 World Health Organization. Tuberculosis and air travel. Geneva: WHO, 2001.

49 Mendis S, Yach D, Alwan A. Air travel and venous thromboembolism. Bull World Health Org. 2002;80:403-406.

50 Gallus AS, Goghlan DC. Travel and venous thrombosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2002;8:372-378.

51 Chow T, Browne V, Heileson HL, et al. Ginkgo biloba and acetazolamide prophylaxis for acute mountain sickness. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:296-301.

52 Department of State, Bureau of Consular Affairs. Online. Available: http://travel.state.gov/, 6 May 2010.

53 Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australia. Smartraveller. Online. Available: http://www.smartraveller.gov.au, 5 May 2010.

54 Foreign and Commonwealth Office. Online. Available: http://www.fco.gov.uk/en/, 5 May 2010.

55 Leggat PA, Leggat FW. Emergency assistance provided abroad to insured travellers from Australia following the Bali bombing. Travel Med Inf Dis. 2004;2:41-45.

56 Hampson GV, Cook SP, Frederiksen SR. The Australian Defence Force response to the Bali bombing, 12 October 2002. Med J Aust. 2002;77:620-623.

57 Leggat PA, Leggat FW. Assistance provided abroad to insured travellers from Australia following the 2004 Asian Tsunami. Travel Med Inf Dis. 2007;5:47-50.

58 Leggat PA, Heydon JL, Menon A. Safety advice for travelers from New Zealand. J Travel Med. 1998;5:61-64.

59 Hill DR, Behrens RH. A survey of travel clinics throughout the world. J Travel Med. 1996;3:46-51.

60 Leggat PA. Travel health advice provided by inflight magazines of international airlines in Australia. J Travel Med. 1997;4:102-103.