CHAPTER 341 Traumatic Cerebrospinal Fluid Fistulas

CSF fistulas may also be iatrogenic, such as after pituitary transsphenoidal surgery or sinus surgery, or may be spontaneous. In addition, CSF leakage can occur after compound vault wounds. These injuries are treated by repair of the dural tear and careful wound closure (see Chapter 339). Fistulas associated with skull base fractures form the subject of this chapter.

The most common sign of a fistula is leakage of CSF from the nose or ear. A fistula may also be indicated by intracranial air (pneumocephalus), with or without leakage of CSF, and be implied by a cranial infection (meningitis or abscess) occurring at any time after a skull base fracture. The frequency of skull base fractures increases with the force applied to the cranium.1 Consequently, CSF fistulas are more common after severe head injuries, and for this reason they may be overlooked initially. It is therefore important to have a high degree of suspicion with head injuries associated with skull base fractures, whether closed or penetrating. Fistulas may also occur with midface fractures of the Le Fort III pattern, without an associated head injury. Most fistulas heal spontaneously, particularly when the primary impact is to the facial skeleton.2 The advice of earlier neurosurgeons that “dural repair should be considered in all cases of paranasal sinus fracture with rhinorrhea, whether this is of early onset, or brief or long duration”3 no longer holds true.

Epidemiology

The causes of CSF fistula reflect the causes of neurotrauma in the community. In general, the most common causes in order of frequency are motor vehicle accidents, falls, and assaults.4,5 In series in which facial fractures dominate, there is a higher frequency of assaults and motor bike accidents. The reported incidence of skull base fractures after nonpenetrating head injury ranges from 7% to 24% and that of associated CSF fistulas from 2% to 20.8% after head injury.6,7 The incidence of skull base fractures increases with the severity of head injury; however, rhinorrhea can develop after minor head injury or primary facial impact in which there has been little or no loss of consciousness.8 Cranionasal fistulas are more common than cranioaural fistulas and less likely to cease spontaneously.9

Pathophysiology

Blunt Injury

Anterior Fossa

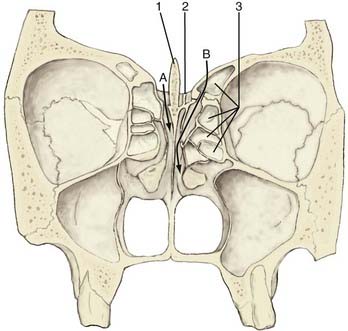

Rhinorrhea is most often caused by a fracture of the frontal, ethmoid, or sphenoid bones. The dura is firmly adherent to the thin bone of the anterior fossa floor and is readily torn by fractured bone edges. The most frequent site of rhinorrhea is the cribriform/ethmoid junction and the ethmoid bone itself.10 The anterior ethmoidal artery penetrates the skull base at the lateral margin of the cribriform plate, thereby creating a natural weakness at that point (Fig. 341-1).11 Fistulas in this region communicate with the nasal cavity directly or via the ethmoid air cells.

Middle and Posterior Fossa

Between 70% and 90% of temporal bone fractures are parallel to the long axis of the petrous ridge. These longitudinal fractures may damage the ossicular bones and result in conductive hearing loss, as well as damage to the seventh nerve. The tympanic membrane is often torn. A transverse fracture (10% to 30%) is more commonly associated with eighth nerve deficits, sensory neural hearing loss, and facial palsy.12 The tympanic membrane is usually intact and CSF will leak via the nose (otorhinorrhea).

CSF fistulas occur with equal frequency with either type of fracture.

A middle fossa fracture that extends to the greater wing of the sphenoid may enter a lateral extension of the sphenoid sinus, which is present in nearly a third of skulls, and result in rhinorrhea.13

Oculorhinorrhea

Rarely, a cranio-orbital fracture together with a laceration of the conjunctival sac may allow CSF to leak from the eye.14,15

Penetrating Injury and Gunshot Wounds

Traumatic CSF leaks may also result from penetrating injuries, including gunshot wounds. Penetrating missile injuries of the skull vault have a high incidence of skull base fractures, 30% of which are discontinuous (i.e., not in continuity with the vault fractures).10 Either rhinorrhea or otorrhea may develop in approximately 50% of these injuries.16 High-velocity missile injuries can cause substantial bony and soft tissue loss and disruption, and repair and reconstruction are often complex (see Chapter 339).

Cerebrospinal Fluid Fistulas in Children

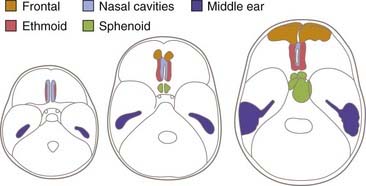

CSF fistulas are less common in childhood, with only 15% occurring in children younger than 15 years. The low frequency in children is due partly to a lower frequency of frontal impact but also to the greater flexibility of the cartilaginous components of the skull base and underdevelopment of the sinuses.17 The frontal sinus is not developed until the age of 4 years or older. The ethmoid sinuses are present at birth and enlarge rapidly, but the ethmoid component of the anterior fossa is cartilaginous and therefore flexible at birth. By the age of 3 years, the nasoethmoid cavities are proportionately equivalent to their size in adults. The sphenoid sinus is very small at birth and becomes related to the anterior fossa between 5 and 10 years of age. The tegmen tympani is thin and rigid at birth, and a fistula to the middle ear is possible. Mastoid air cells are very small at birth but increase up to the age of 5 years (Fig. 341-2).

Time of Onset of Leakage of Cerebrospinal Fluid after Trauma

Early Onset

After nonpenetrating injuries, CSF rhinorrhea usually begins within 48 hours.4,5,7,18 If the defect is small, the bone may heal, and 60% to 70% of cases will cease spontaneously within 1 week.8

Delayed Onset or Recurrence

Very-Late-Onset Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage or Infection

CSF rhinorrhea may first develop after a considerable delay, or infection alone may be the first sign of a fistula. Delayed meningitis without a history of CSF rhinorrhea has been reported up to 48 years after the original head injury, which might have been quite minor.22–24

Cranioaural Fistula

Most cases of traumatic otorrhea and otorhinorrhea cease spontaneously. In a large series, less than 5% persisted more than 14 days.26 Hence, most can be treated conservatively.27 Nonetheless, the incidence of meningitis while awaiting spontaneous healing has been reported to be as high as 18%.9

High- and Low-Pressure Leaks

In the early stages after severe head injury, potentially increased ICP may be partly “controlled” by a CSF leak, but in most instances persistent fistulas are not associated with increased ICP. High-pressure leaks are more common with spontaneous, nontraumatic CSF leakage; however, if the leak is accompanied by posttraumatic hydrocephalus, it may be maintained by the high CSF pressure, and the hydrocephalus should be managed by insertion of a lumbar peritoneal shunt as the initial treatment.19

Intracranial Air (Pneumocephalus)

Intracranial air is present in 20% to 30% of patients with posttraumatic CSF fistulas, but it may also occur without rhinorrhea.28 Alone, it carries the same risk for meningitis as a CSF leak does.29

The mechanism of pneumocephalus is debated.30,31 It may be caused by a ball-valve effect combined with episodic increased pressure within the nasopharynx on coughing or by an “inverted bottle” effect whereby there is a discontinuous exchange of air and CSF when change in posture reduces ICP below atmospheric.

Tension pneumocephalus is an uncommon but serious complication.32

Clinical Features

History

The history usually consists of a head or facial injury from a frontal impact. A profuse leak is readily identified, but small and intermittent leaks are often overlooked, particularly if the CSF is mixed with blood and mucus. In an unconscious patient with signs of a skull base fracture, evidence of CSF leakage should be sought actively. A conscious patient may complain of a nasal discharge or a salty taste in the back of the throat (because of the sodium content of CSF) or fullness of the ear with some hearing loss. A large volume of fluid leaking from the nose or ear with change in head position indicates that a CSF-filled sinus has drained (reservoir sign).33 Patients may complain of nasal dripping in the morning after sitting up, leaning forward, or straining.

Examination

Neurological examination may provide valuable localizing information. Anosmia suggests a fracture of the anterior cranial fossa at or near the cribriform plate; however, intact olfaction does not exclude the possibility of a cribriform fracture.32 Seventh or eighth nerve palsies and impaired balance suggest a fracture of the temporal bone involving the labyrinth. Defects in vision or visual fields indicating optic nerve injury and sensory loss of the first division of the trigeminal nerve suggest fracture of the anterior fossa.

The side of rhinorrhea cannot be relied on to locate the fistula. Although usually ipsilateral to the fracture site, it is frequently contralateral or bilateral.3,32

Investigation

Identifying Cerebrospinal Fluid

Bedside Tests

Glucose oxidized test strips have been used for many years to test for the presence of CSF. The test strips are positive at a relatively low level of glucose—greater than 20 mg/100 mL. Nasal secretion contains approximately 10 mg of glucose; however, nasal mucus and lachrymal gland secretions have reducing substances that may cause a positive reaction with glucose concentrations as low as 5 mg/dL. Hence, a negative glucose strip test eliminates the likelihood of a CSF leak, but a positive result cannot be interpreted.34 Furthermore, because blood contains glucose, the test must be conducted on clear discharge.

Laboratory Tests

β2-Transferrin

β2-Transferrin is a polypeptide involved in ferrous iron transport. β1-Transferrin is found in serum, tears, nasal secretions, and saliva. β2-Transferrin is found only in CSF, perilymph, and vitreous humor. It accounts for 15% of the total transferrin in CSF. It is important to determine the presence of penetrating eye injury before interpreting the β2-transferrin results. Quantitative detection of β2-transferrin can be performed on a small volume of fluid (<1 mL). The results of agarose gel electrophoresis are available in 3 hours, and it is the most sensitive and specific test to date.35,36 One study has indicated that there can be false-positive results.37 If this test is not available, glucose and chlorine concentrations help identify CSF.

Glucose Concentration

The glucose concentration can be assessed with 0.5 to 1 mL of fluid. If the glucose content is 0.5 to 0.67 that of the serum glucose concentration, the fluid is most likely CSF. It is important to take into account clinical conditions that alter the level of glucose in CSF and serum.34

Locating the Fistula

Computed Tomography

Fine-Cut Bone Window Scans

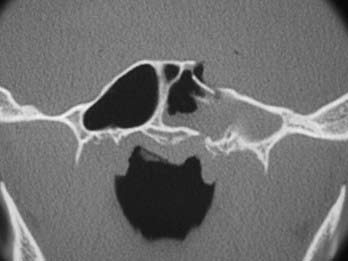

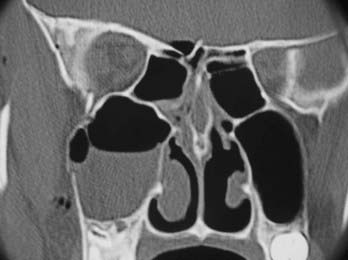

For examining the skull base, the standard format consists of fine cuts (0.6- to 1-mm intervals) performed on a helical multislice CT scanner at bone and soft tissue window levels. This protocol results in a box of data that can be sliced by the scanner in any plane. For best definition, the axis of scanning should be at right angles to the plane of the bone being examined. Thus, axial bone scans show the walls of the frontal sinuses, whereas coronal scans show the ethmoid complex, the roof of the sphenoid sinus, and the tegmen of the middle ear. The pattern of fracture lines and the presence of comminuted fractures, spikes, and wide fractures should be noted (Figs. 341-3 and 341-4).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been reported to be a useful, noninvasive adjunct in the investigation of CSF rhinorrhea, particularly in the presence of inflammatory sinus disease.39 It may distinguish between mucosal disease with mucopurulent discharge and CSF, which may show the same radiopacity on a CT scan. On T2-weighted images, CSF will appear white and perimucosal discharge and nasal disease will be darker. Mucosal disease can be highlighted by the administration of gadolinium. MRI signs indicative of a CSF fistula include brain arachnoid hernia through the bone defect and a CSF signal in the perinasal sinuses that is continuous with intracranial CSF. A fistula may also be suspected if there is fluid in only one of the paranasal sinuses even though the fluid is not continuous with intracranial CSF. One study found that MRI was 100% successful and superior to CT cisternography in detecting active CSF leaks.40 However, another study found the T2 signs reported to be relevant to the identification of a fistula to lack useful specificity.41

Tracer Studies

Intrathecal Fluorescein

Fluorescein injected intrathecally may be detected on cottonoid pledgets placed in the nasopharynx or during endoscopic examination.42–47 Ten milliliters of CSF is withdrawn by lumbar puncture, mixed with 0.2 to 0.5 mL of 5% fluorescein, and slowly reinjected through a lumbar drain filter over a 10-minute period.42,45,46 This is done while the patient is awake so that any adverse effects are apparent immediately. The patient is placed in the reverse Trendelenburg position to facilitate diffusion of the fluorescein intracranially. In most cases this is done in the anesthetic recovery room at the beginning of the operating schedule, which allows the patient to remain in recovery for a few hours before surgery. This approach allows time for diffusion of the fluorescein into the intracranial cavity. If this is not possible, at least 30 minutes should be allowed for diffusion to occur before surgery is undertaken. Before endoscopic sinus surgery, the eustachian tube orifice needs to be inspected to ensure that CSF is not draining from the middle ear to the eustachian tube. The patient is then taken to the operating room.

Although intrathecal fluorescein has been reported to be safe at these concentrations,42–46 there have been reports in the past of numbness and weakness of the lower extremities, opisthotonos, and seizures when higher concentrations were used. If an adverse reaction does occur, saline irrigation to clear the lumbar CSF and elevation of the head to limit side effects to the lower extremities have been recommended.

Computed Tomographic Cisternography

If there is an active leak, CT cisternography can demonstrate a fistula in 76% to 100% of cases. If no leak is present at the time of the investigation, the rate of detection is lower.48,49 After a baseline scan, 6 to 7 mL of metrizamide or iopamidol is injected via a lateral C1-2 puncture or lumbar puncture in the screening room with the patient prone. The contrast medium is then manipulated into the basal subarachnoid space. Coronal images are obtained from the frontal sinuses to the dorsum sellae and, if indicated, the petrous bone. The site of the leak is indicated by bone dehiscence, contrast agent in the adjacent paranasal sinus, and distortion of the subarachnoid space, findings indicative of brain herniation.40,50,51

Management

Infection

Meningitis is the most serious complication of CSF fistulas. Untreated, CSF rhinorrhea has been associated with a 25% risk for meningitis.3 Early leaks have been associated with a 6% to 20% incidence of meningitis and delayed leaks with up to a 57% incidence.3,5,9,55–58 Daudia and colleagues calculated an overall risk of 19% for those with persisting leakage, the risk being greatest in the first year and progressively decreasing with time.55

Although most fistulas heal spontaneously, the incidence of meningitis while awaiting a decision on surgical repair is about 11%.59 The mortality rate for meningitis resulting from a traumatic CSF fistula has been reported to be 10%.60 Risk for meningitis is greater with

Any basal skull fracture potentially allows direct communication between the subarachnoid space and the exterior. There is a 2.6 times greater rate of intracranial infection with basal skull fractures when a ventricular catheter is used.61 Because the risk of infection is considerably lower with lumbar catheters, the use of ventricular catheters in patients with basal fractures must have a sound clinical indication.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis

The value of antibiotic prophylaxis continues to be debated,62 with some reports showing increased infection with antibiotic treatment.63,64 A review of the Mayo Clinic experience found that infection was halved in those treated with prophylactic antibiotics.65 Although one meta-analysis recorded a 2.5% incidence of infection with antibiotics and 10% without,63 another found no benefit.66 Only two double-blind studies have been conducted; they were inconclusive regarding the incidence of meningitis but showed no increase in other significant infections.67,68

Arguments against antibiotic prophylaxis are as follows:

Definitive Treatment

Conservative Care versus Surgery

Initial conservative treatment is indicated if CT scans show undisplaced and linear fractures because spontaneous healing is likely. Patients with a facial impact but without a vault fracture may be treated by reduction of the facial fractures and initial conservative treatment of the rhinorrhea.2

Conservative treatment consists of the following:

If the leak does not cease within 3 days, intermittent or continuous drainage of lumbar fluid may be considered.6,69–71 Continuous CSF drainage is potentially hazardous and should be used with caution. Overdrainage can lead to intracranial aeroceles, severe brain displacement, and coma72,73 and require emergency drainage of the aerocele.74 Intermittent drainage of 20 to 30 mL over an 8-hour period into a closed system is safer. If continuous drainage is used, the drain should be placed no lower than shoulder height with the head elevated about 10 to 15 degrees. It has been suggested but not proved that lumbar drainage may promote the entry of bacteria through the fistula, as well as impose its own risk for infection at the site of the spinal catheter; however, it is still preferable to ventricular drainage.

Timing of Surgery

Repair of Anterior Fossa Fistulas

Operative Procedure

Some authors recommend first identifying the dural tear extradurally or a combined intradural-extradural approach75; however, in general, intradural exploration allows clearer delineation of the dural tear, does not risk creating false tears, and permits more definitive repair.

If no fistula is found after careful exploration, the operation should cease and radiographs should be thoroughly reviewed for any other possible sites, such as the middle or posterior fossa. Avulsion of intact olfactory nerves and covering the entire anterior fossa floor with fascia are not recommended. If no other site is suggested by review and the leak is small, it may be treated indirectly with a lumbar peritoneal shunt.70

Frontal Sinus Fractures

A bicoronal scalp flap is turned down and a small craniotomy is cut low across the frontal sinus. The dura is explored extradurally and the tear repaired in watertight manner. The posterior wall of the sinus is excised, the sinus mucosa stripped, and the frontal nasal duct plugged with fat or muscle. The anterior wall is replaced and reconstituted with miniplates (see also Chapter 339).

Endoscopic Repair

Anterior and Posterior Cranial Fossa Cerebrospinal Fluid Leaks

The first and most important step is to identify the site of CSF leakage.42,43,45–47 As described earlier, this is done by identifying the most likely site of the leak on fine-cut CT scans and then approaching this region endoscopically and clearly delineating the leak by visualizing fluorescein-stained CSF leaking from the defect.

The probable site of the leak can usually be identified by fractures of the skull base or isolated fluid within a sinus (see Figs. 341-3 and 341-4). Surgical access to this site is then planned. If the site involves the posterior wall of the frontal sinus, an endoscopic modified Lothrop technique (endoscopic frontal sinus drill-out procedure) is performed to expose the frontal sinuses widely and provide access to the posterior wall. If the site is the cribriform plate, a middle turbinectomy with or without ethmoidectomy will give good exposure. If the leak is in the roof of the ethmoids (fovea ethmoidalis), endoscopic ethmoidectomy is needed. If the site is the roof of the sphenoid, lateral wall (middle cranial fossa), or posterior wall (posterior cranial fossa), endoscopic sphenoidotomy provides good exposure to these areas. When the sphenoid is very pneumatized and the leak is from the lateral wall of the sphenoid, a transpterygoid approach is required. After a large middle meatal antrostomy is performed, the posterior bony wall overlying the pterygopalatine fossa is removed to expose the pterygopalatine fossa. In this approach the vidian nerve, pterygopalatine ganglion, and sphenopalatine artery are removed from the pterygopalatine fossa with preservation of the infraorbital nerve. This exposes the anterior wall of the pneumatized sphenoid, which is removed with a diamond bur to provide a direct approach to the lateral wall and CSF leak in a pneumatized sphenoid.

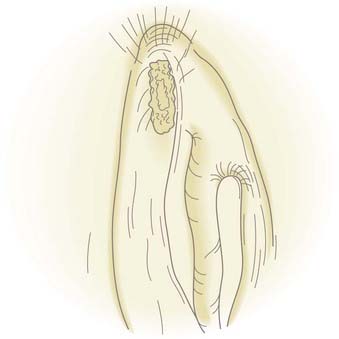

![]() Once the leak is clearly identified, the nasal or sinus mucosa around the site of the leak is removed for about 5 mm to expose the bone around the defect (Fig. 341-5, Video 341-1).42,45,46 This allows attachment of the free graft to the bone and improves the seal of the repair. If any loose bony fragments are seen around the bone defect, they are gently removed. If the dural defect is significantly smaller than the bony defect, the dural defect is enlarged to the size of the bony defect. Attempting to repair a dural defect without bone support is associated with a high incidence of failure and is not recommended.

Once the leak is clearly identified, the nasal or sinus mucosa around the site of the leak is removed for about 5 mm to expose the bone around the defect (Fig. 341-5, Video 341-1).42,45,46 This allows attachment of the free graft to the bone and improves the seal of the repair. If any loose bony fragments are seen around the bone defect, they are gently removed. If the dural defect is significantly smaller than the bony defect, the dural defect is enlarged to the size of the bony defect. Attempting to repair a dural defect without bone support is associated with a high incidence of failure and is not recommended.

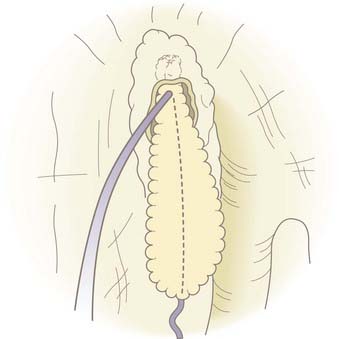

Once the defect has been prepared, it is measured with a curet. If the size of the defect is less than 8 mm in diameter, a fat plug is harvested from the earlobe. If the dural defect is greater than 8 mm, there is not sufficient fat in the earlobe to create a fat plug of that size, so fat is harvested from the lateral aspect of the thigh or abdomen. The fat of the earlobe is preferred because the fat globules are tightly bound and easy to work with whereas lateral thigh fat and even more so abdominal fat are very loosely bound and tend to fall apart during manipulation. The fat plug should be the same diameter as the dural defect and about 1.5 cm long. Using a 40 Vicryl Rapide suture, a knot is placed at the apex of the fat plug and the needle run down the length of the fat plug (Fig. 341-6).

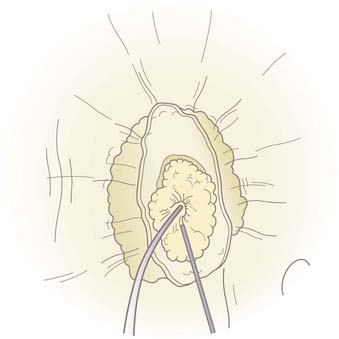

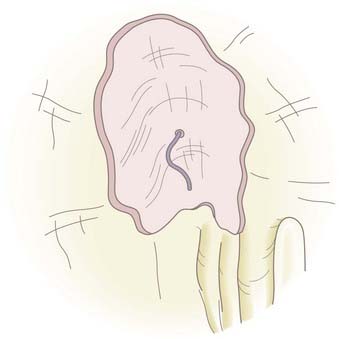

A malleable frontal sinus probe (Medtronic ENT, Jacksonville, FL) is used to introduce the fat plug with attached suture into the intracranial cavity. It is important that the fat be introduced by pushing a small amount of fat from directly adjacent to the defect through the defect without the probe passing more than a few millimeters intracranially. This limits the potential for injury to intracranial structures. It is also important to not place the probe at the base of the fat plug because pushing too far back on the plug will cause it to expand so that its diameter will become larger than the defect and the plug will not go through the defect. Once the plug is through the defect and within the intracranial cavity, the probe is placed below the defect to support the plug while the suture is gently pulled. This expands the fat plug in the intracranial space and causes the plug to be larger than the defect. The fat plug will fill the defect, and a small amount will prolapse through and create an immediate complete seal of the CSF leak (Fig. 341-7). Quite firm traction is placed on the plug at this point. Once the plug is in position, the anesthetist is asked to briefly raise intrathoracic pressure (Valsalva maneuver), and the seal is checked. Even a very small residual leak is clearly evident because of fluorescein staining of the CSF. The plug should achieve a complete seal, but if not, it should be removed and a slightly larger plug placed until a complete seal is produced. A free mucosal graft is harvested from the lateral nasal wall and slid up the suture to cover the fat plug. If available, fibrin or synthetic bioglue is used to seal this graft in place. The suture is cut just below this graft and Gelfoam is placed over it (Fig. 341-8). The nasal cavity can be packed, but in most cases this is not necessary. CSF pressure will keep the fat plug in place, much as bath water keeps the bath plug in place and watertight.

Postoperatively, the patient receives broad-spectrum antibiotics for 5 days (if no packs) or 10 days (if nasal packs are placed), and the nose is douched with saline four to six times a day for a few weeks to remove secretions and blood clot from the nasal cavity. The techniques described achieve a 96% success rate with the first closure and 100% for the few cases that may fail after the initial closure.42,45,46,76

Cerebrospinal Fluid Shunting

Briggs RJ, Wormald PJ. Endoscopic transnasal intradural repair of anterior skull base cerebrospinal fluid fistulae. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11:597.

Brodie HA. Prophylactic antibiotics for posttraumatic cerebrospinal fluid fistulae. A meta-analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:749.

Colquhoun IR. CT cisternography in the investigation of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea. Clin Radiol. 1993;47:403.

Daudia A, Biswas D, Jones NS. Risk of meningitis with cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116:902.

Eljamel MS, Foy PM. Post-traumatic CSF fistulae, the case for surgical repair. Br J Neurosurg. 1990;4:479.

Friedman JA, Ebersold MJ, Quast LM. Persistent posttraumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9(1):e1.

Graf CJ, Gross CE, Beck DW. Complications of spinal drainage in the management of cerebrospinal fluid fistula. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:392.

Hegazy HM, Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, et al. Transnasal endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: a meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1166.

Hubbard JL, McDonald TJ, Pearson BW, et al. Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: evolving concepts in diagnosis and surgical management based on the Mayo Clinic experience from 1970 through 1981. Neurosurgery. 1985;16:314.

Lewin W. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea in nonmissile head injuries. Clin Neurosurg. 1966;12:237.

McCormack B, Cooper PR, Persky M, et al. Extracranial repair of cerebrospinal fluid fistulas: technique and results in 37 patients. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:412.

Meirowsky AM, Caveness WF, Dillon JD, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid fistulas complicating missile wounds of the brain. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:44.

Ommaya A. Spinal fluid fistulae. Clin Neurosurg. 1975;23:363.

Ryall RG, Peacock MK, Simpson DA. Usefulness of beta 2-transferrin assay in the detection of cerebrospinal fluid leaks following head injury. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:737.

Salame K, Segev Y, Fliss DM, et al. Diagnosis and management of posttraumatic oculorrhea. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9(1):e3.

Shetty PG, Shroff MM, Sahani DV, et al. Evaluation of high-resolution CT and MR cisternography in the diagnosis of cerebrospinal fluid fistula. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:633.

Stammberger H, Greistorfer K, Wolf G, et al. [Surgical occlusion of cerebrospinal fistulas of the anterior skull base using intrathecal sodium fluorescein.]. Laryngorhinootologie. 1997;76:595.

Villalobos T, Arango C, Kubilis P, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis after basilar skull fractures: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:364.

Wormald PJ, McDonogh M. The bath-plug closure of anterior skull base cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Am J Rhinol. 2003;17:299.

Wormald PJ, McDonogh M. “Bath-plug” technique for the endoscopic management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:1042.

1 Eisenberg HM, Gary HEJr, Aldrich EF, et al. Initial CT findings in 753 patients with severe head injury. A report from the NIH Traumatic Coma Data Bank. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:688.

2 Jefferson A, Reilly G. Fractures of the floor of the anterior cranial fossa. The selection of patients for dural repair. Br J Surg. 1972;59:585.

3 Lewin W. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea in closed head injuries. Br J Surg. 1954;42:1.

4 Eljamel MS, Foy PM. Post-traumatic CSF fistulae, the case for surgical repair. Br J Neurosurg. 1990;4:479.

5 Park JI, Strelzow VV, Friedman WH. Current management of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. Laryngoscope. 1983;93:1294.

6 Brawley BW, Kelly WA. Treatment of basal skull fractures with and without cerebrospinal fluid fistulae. J Neurosurg. 1967;26:57.

7 Brisman R, Hughes JEO, Mount LA. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. Arch Neurol. 1966;22:245.

8 Mincy JE. Posttraumatic cerebrospinal fluid fistula of the frontal fossa. J Trauma. 1966;6:618.

9 Leech PJ, Paterson A. Conservative and operative management for cerebrospinal-fluid leakage after closed head injury. Lancet. 1973;1:1013.

10 Johnson RT, Dutt P. On dural laceration over paranasal and petrous air sinuses. Br J Surg (War Surg Suppl 1). 1947:141.

11 Calcaterra TC. Diagnosis and management of ethmoid cerebrospinal rhinorrhea. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1985;18:99.

12 Hicks GW, Wright JWJr. Wright JW 3rd. Cerebrospinal fluid otorrhea. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:1.

13 Morley TP, Wortzman G. The importance of the lateral extensions of the sphenoidal sinus in post-traumatic cerebrospinal rhinorrhoea and meningitis: clinical and radiological aspects. J Neurosurg. 1965;22:326.

14 Joshi KK, Crockard HA. Traumatic cerebrospinal fluid fistula simulating tears. Case report. J Neurosurg. 1978;49:121.

15 Salame K, Segev Y, Fliss DM, et al. Diagnosis and management of posttraumatic oculorrhea. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9(1):e3.

16 Meirowsky AM, Caveness WF, Dillon JD, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid fistulas complicating missile wounds of the brain. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:44.

17 Caldicott WJ, North JB, Simpson DA. Traumatic cerebrospinal fluid fistulas in children. J Neurosurg. 1973;38:1.

18 Lewin W. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea in nonmissile head injuries. Clin Neurosurg. 1966;12:237.

19 Ommaya A. Spinal fluid fistulae. Clin Neurosurg. 1975;23:363.

20 McCormack B, Cooper PR, Persky M, et al. Extracranial repair of cerebrospinal fluid fistulas: technique and results in 37 patients. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:412.

21 Okada J, Tsuda T, Takasugi S, et al. Unusually late onset of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea after head trauma. Surg Neurol. 1991;35:213.

22 Crawford C, Kennedy N, Weir WR. Cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea and Haemophilus influenzae meningitis 37 years after a head injury. J Infect. 1994;28:93.

23 Salca HC, Danaila L. Onset of uncomplicated cerebrospinal fluid fistula 27 years after head injury: case report. Surg Neurol. 1997;47:132.

24 Schick B, Weber R, Kahle G, et al. Late manifestations of traumatic lesions of the anterior skull base. Skull Base Surg. 1997;7:77.

25 Talamonti G, Fontana RA, Versari PP, et al. Delayed complications of ethmoid fractures: a “growing fracture” phenomenon. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;137:164.

26 Chandler JR. Traumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1983;16:623.

27 Savva A, Taylor MJ, Beatty CW. Management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks involving the temporal bone: report on 92 patients. Laryngoscope. 2003;113:50.

28 Bakay L, Glasauer FE. Head Injury. Boston: Little Brown; 1980.

29 North JB. On the importance of intracranial air. Br J Surg. 1971;58:826.

30 Lunsford LD, Maroon JC, Sheptak PE, et al. Subdural tension pneumocephalus. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1979;50:525.

31 Walker FO, Vern BA. The mechanism of pneumocephalus formation in patients with CSF fistulas. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1986;49:203.

32 Hubbard JL, McDonald TJ, Pearson BW, et al. Spontaneous cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: evolving concepts in diagnosis and surgical management based on the Mayo Clinic experience from 1970 through 1981. Neurosurgery. 1985;16:314.

33 Kaufman B, Nulsen FE, Weiss MH, et al. Acquired spontaneous, nontraumatic normal-pressure cerebrospinal fluid fistulas originating from the middle fossa. Radiology. 1977;122:379.

34 Buchanan RJ, Brant A, Marshall LF. Traumatic cerebrospinal fluid fistulas, 5th ed. Winn HR, editor. Youmans Neurological Surgery, Vol 4. Philadelphia: WB Saunders. 2004.

35 Meurman OH, Irjala K, Suonpaa J, et al. A new method for the identification of cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Acta Otolaryngol. 1979;87:366.

36 Ryall RG, Peacock MK, Simpson DA. Usefulness of beta 2-transferrin assay in the detection of cerebrospinal fluid leaks following head injury. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:737.

37 Sloman AJ, Kelly RH. Transferrin allelic variants may cause false positives in the detection of cerebrospinal fluid fistulae. Clin Chem. 1993;39:1444.

38 Shetty PG, Shroff MM, Sahani DV, et al. Evaluation of high-resolution CT and MR cisternography in the diagnosis of cerebrospinal fluid fistula. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1998;19:633.

39 Eljamel MS, Pidgeon CN. Localization of inactive cerebrospinal fluid fistulas. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:795.

40 Johnson DB, Brennan P, Toland J, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging in the evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid fistulae. Clin Radiol. 1996;51:837.

41 Hegarty SE, Millar JS. MRI in the localization of CSF fistulae: is it of any value? Clin Radiol. 1997;52:768.

42 Briggs RJ, Wormald PJ. Endoscopic transnasal intradural repair of anterior skull base cerebrospinal fluid fistulae. J Clin Neurosci. 2004;11:597.

43 Casiano RR, Jassir D. Endoscopic cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea repair: is a lumbar drain necessary? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121:745.

44 Syms CA3rd, Syms MJ, Murphy TP, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid fistulae in a canine model. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117:542.

45 Wormald PJ, McDonogh M. “Bath-plug” technique for the endoscopic management of cerebrospinal fluid leaks. J Laryngol Otol. 1997;111:1042.

46 Wormald PJ, McDonogh M. The bath-plug closure of anterior skull base cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Am J Rhinol. 2003;17:299.

47 Stammberger H, Greistorfer K, Wolf G, et al. [Surgical occlusion of cerebrospinal fistulas of the anterior skull base using intrathecal sodium fluorescein.]. Laryngorhinootologie. 1997;76:595.

48 Chow JM, Goodman D, Mafee MF. Evaluation of CSF rhinorrhea by computerized tomography with metrizamide. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;100:99.

49 Schaefer SD, Diehl JT, Briggs WH. The diagnosis of CSF rhinorrhea by metrizamide CT scanning. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:871.

50 Ahmadi J, Weiss MH, Segall HD, et al. Evaluation of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea by metrizamide computed tomographic cisternography. Neurosurgery. 1985;16:54.

51 Colquhoun IR. CT cisternography in the investigation of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea. Clin Radiol. 1993;47:403.

52 Aydin K, Terzibasioglu E, Sencer S, et al. Localization of cerebrospinal fluid leaks by gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance cisternography: a 5-year single-center experience. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:584.

53 Goel G, Ravishankar S, Jayakumar PN, et al. Intrathecal gadolinium-enhanced magnetic resonance cisternography in cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: road ahead? J Neurotrauma. 2007;24:1570.

54 Reiche W, Komenda Y, Schick B, et al. MR cisternography after intrathecal Gd-DTPA application. Eur Radiol. 2002;12:2943.

55 Daudia A, Biswas D, Jones NS. Risk of meningitis with cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007;116:902.

56 Flanagan JC, McLachlan DL, Shannon GM. Orbital roof fractures: neurologic and neurosurgical considerations. Ophthalmology. 1980;87:325.

57 Jamieson KG, Yelland JD. Surgical repair of the anterior fossa because of rhinorrhea, aerocele, or meningitis. J Neurosurg. 1973;39:328.

58 Koso-Thomas AK, Harley EH. Traumatic cerebrospinal fluid fistula presenting as recurrent meningitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;112:469.

59 Eljamel MS, Foy PM. Acute traumatic CSF fistulae: the risk of intracranial infection. Br J Neurosurg. 1990;4:381.

60 Luerssen TG, Chesnut RM, van Berkum-Clark M, et al. Post traumatic cerebrospinal fluid infections in the Traumatic Coma Data Bank: The influence of the type and management of monitoring. In: Avezaat CJJ, van Eiindhoven JHM, Maas AIR, et al, editors. Intracranial Pressure VIII. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1991:42-45.

61 Luerssen TG, Chestnut RM, van Berkum-Clark M, et al. Post traumatic cerebrospinal fluid infections in the Trauma Comatic Bank: The influence of the type and management of monitors. In: Avezaat CJJ, van Eiindhoven JHM, Maas AIR, et al., eds. Intracranial Pressure VIII Data, Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1991:42-45.

62 Choi D, Spann R. Traumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage: risk factors and the use of prophylactic antibiotics. Br J Neurosurg. 1996;10:571.

63 Brodie HA. Prophylactic antibiotics for posttraumatic cerebrospinal fluid fistulae. A meta-analysis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;123:749.

64 Ignelzi RJ, VanderArk GD. Analysis of the treatment of basilar skull fractures with and without antibiotics. J Neurosurg. 1975;43:721.

65 Friedman JA, Ebersold MJ, Quast LM. Persistent posttraumatic cerebrospinal fluid leakage. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;9(1):e1.

66 Villalobos T, Arango C, Kubilis P, et al. Antibiotic prophylaxis after basilar skull fractures: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:364.

67 Demetriades D, Charalambides D, Lakhoo M, et al. Role of prophylactic antibiotics in open and basilar fractures of the skull: a randomized study. Injury. 1992;23:377.

68 Klastersky J, Sadeghi M, Brihaye J. Antimicrobial prophylaxis in patients with rhinorrhea or otorrhea: a double-blind study. Surg Neurol. 1976;6:111.

69 Dalgic A, Okay HO, Gezici AR, et al. An effective and less invasive treatment of post-traumatic cerebrospinal fluid fistula: closed lumbar drainage system. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2008;51:154.

70 Greenblatt SH, Wilson DH. Persistent cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea treated by lumboperitoneal shunt. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 1973;38:524.

71 Shapiro SA, Scully T. Closed continuous drainage of cerebrospinal fluid via a lumbar subarachnoid catheter for treatment or prevention of cranial/spinal cerebrospinal fluid fistula. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:241.

72 Graf CJ, Gross CE, Beck DW. Complications of spinal drainage in the management of cerebrospinal fluid fistula. J Neurosurg. 1981;54:392.

73 Kamat AA, Bhattacharyya D, Carroll TA. Brain sag as a cause of postoperative neurological deterioration following anterior cranial fossa floor repair for post traumatic cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhoea. Br J Neurosurg. 2007;21:303.

74 Dewaele F, Caemaert J, Baert E, et al. Intradural endoscopic closure of dural breaches in a case of post-traumatic tension pneumocephalus. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2007;50:178.

75 Scholsem M, Scholtes F, Collignon F, et al. Surgical management of anterior cranial base fractures with cerebrospinal fluid fistulae: a single-institution experience. Neurosurgery. 2008;62:463.

76 Hegazy HM, Carrau RL, Snyderman CH, et al. Transnasal endoscopic repair of cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea: a meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1166.

77 Spetzler RF, Wilson CB. Management of recurrent CSF rhinorrhea of the middle and posterior fossa. J Neurosurg. 1978;49:393.