60 Trauma to the Spine and Spinal Cord

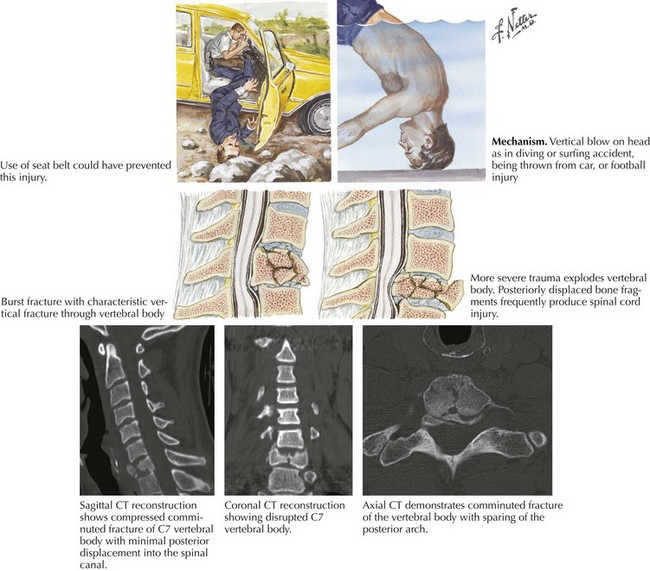

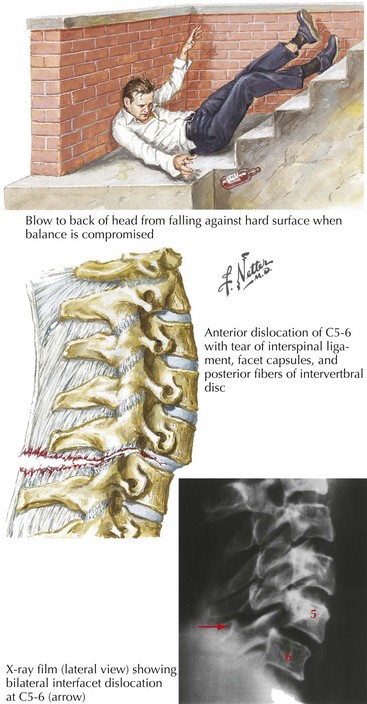

Major trauma centers evaluate two to three TSCI individuals out of every 100 patients brought to their emergency departments. The very high mortality (50%) associated with TSCI occurs mainly at the initial accident scene. Most often, these patients are accidentally injured while in an automobile (Fig. 60-1) or on a motorbike, particularly motorcycles. This type of injury also predisposes the patient to multiple-organ damage, for example, brain shear injury and/or intracerebral or subdural/epidural hematoma, cardiac tamponade, or a ruptured aorta, often leading to their very substantial fatality rate. In contrast, nonvehicular spinal cord injuries often occur with falls in (Fig. 60-2) or near the home (Fig. 60-3).

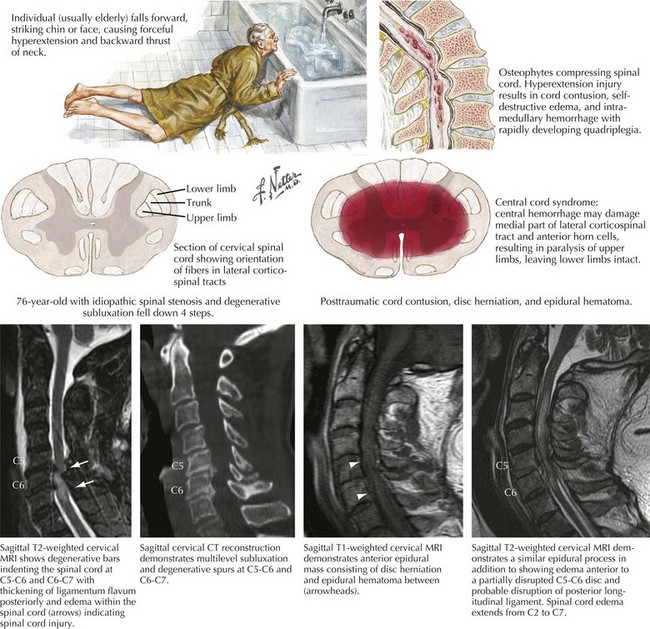

These patients have a 16% mortality rate if they survive to get to the hospital. Young men sustain 85% of TSCI, and thus there is a high correlation with alcohol, motor vehicle accidents, or athletic injuries usually from contact sports or on occasion skiing, diving, or trampolines. In the older population, individuals having significant predisposing cervical spinal spondylosis and/or stenosis are much more likely to develop TSCIs, a central cord injury (Fig. 60-2), from relatively simple falls on stairs or precipitously while navigating icy walkways.

Pathophysiology

Different types of trauma can lend themselves to severe spinal cord injury. One of the most well-known, particularly among adolescents, is that related to diving or vehicular trauma leading to compression damage to the spine and concomitantly the spinal cord (see Fig. 60-1). The more senior population is primarily subject to TSCI in relation to seemingly simple falls in the home (see Fig. 60-2); similarly, alcoholics or abusers of other drugs are also at significantly increased risk of spinal cord trauma (see Fig. 60-3).

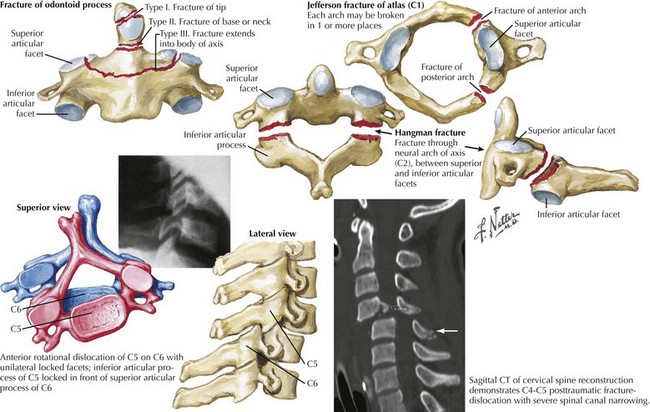

In addition to the various types of trauma to the vertebrae per se (Fig. 60-4), there may be gross external cord trauma varying from a simple contusion to a total severing of the proximal from the distal cord, and there is often very significant intramedullary microvascular thrombosis. This is associated with hemorrhage and necrosis secondary to infarction. The hemorrhage is probably venous in origin. Toxic excitatory amines produced by the trauma worsen the secondary injury.

Initial Management

Many spinal cord injuries, particularly of vehicular or wartime origin, have a number of other important associated clinical accompaniments equally demanding immediate focus and intervention. Thus, usually it is not possible to focus on the problems of spine and spinal cord trauma per se as isolated clinical phenomena in such settings. Frequently multisystem injuries are concomitantly present, leading to issues such as hypotension, hypoxia, infection, and the need for surgery on other organ systems. Each and every one of these factors complicates the treatment of the spine injury. The ABCs of Advanced Trauma Life Support, that is, Airway, Breathing, and Circulation, demand immediate medical attention. Because any degree of hypotension and hypoxia will further the intrinsic spinal cord injury, it is absolutely essential that everything be done to minimize any subsequent injury to the contused spinal cord secondary to inadequate blood supply and/or oxygen (Fig. 60-5).

Diagnostic Approach

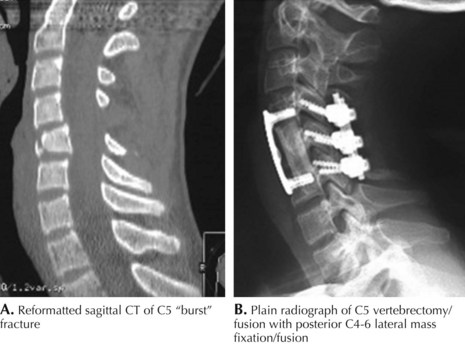

Cervical Spine

Most trauma patients require spinal computed tomographic (CT) examination especially with the alert patient who complains of neck pain, and/or tenderness even when he or she has no obvious neurologic deficits. While the neck is still immobilized, if modern CT scanning is available, spinal CT is indicated. This examination is very rapid and is so elegant that it is our procedure of choice (see Fig. 60-1 and 60-2). It is definitely more useful than plain radiographs as it offers the opportunity to provide reconstruction of the CT data in sagittal, coronal, or any angled plane desirable to the physician. The elegance of modern CT scanning far surpasses the utilization of plane spine radiographs performed with portable technique in the emergency department. However, in settings lacking the rapid CT scan capabilities, standard radiographic imaging still provides very important initial screening for fracture dislocations. This three-view cervical spine study must include lateral, anteroposterior, and open-mouth views of the odontoid. It is essential to visualize the entire cervical spine from the occiput through T1. Whenever this traditional imaging is questionable or just inadequate, thin-cut CT scanning with reconstruction through the questionable areas must be performed. In addition, when caring for any head trauma patient requiring CT, the scanning must always be carried through the cervical spine.

Whenever there is any neurologic injury, an MRI (see Fig. 60-2) is performed before removing the collar or instituting therapy. An MRI will elegantly provide evidence of any spinal cord injury, nerve root pressure, disc herniation, and ligamentous soft tissue injury. A normal examination makes it safe to remove the collar support and allow for early mobilization. This mitigates the possibility of skin breakdown if the patient unnecessarily remains in a hard cervical collar for prolonged periods of time. Formal MRI imaging may not be necessary if the trauma victim is alert, has no neck pain or tenderness, full painless range of motion of the neck, a normal neurologic examination, and no evidence of alcohol or illicit drug use,.

Treatment

Immediate

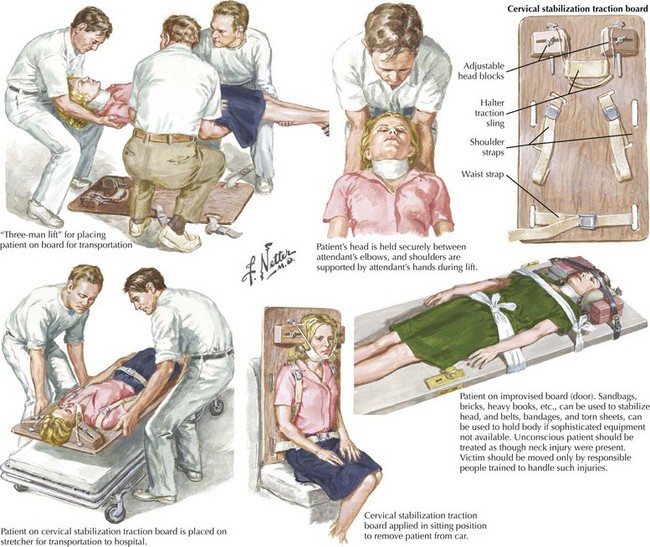

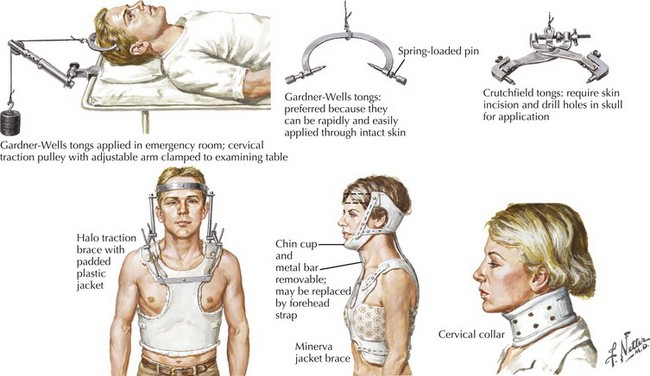

Treatment begins at the accident scene. EMT personnel are trained to safely extract injured patients from the accident location. This may include individuals within or those thrown from a motor vehicle, the presence of a football helmet, or an elderly person who has just taken a fall and is found in an awkward position in the bathroom. Immediate spine immobilization is mandatory; the patient is placed on a back board with his or her neck in a collar, taped to the board with the spine stabilized to prevent secondary injury (see Fig. 60-5). This position must be maintained until the entire spine is clinically, and usually radiologically, cleared by appropriate physicians. Because of spinal instability, 4% of patients with TSCI deteriorate after initial attempts at treatment. Nonoperative spinal stabilizing techniques include a collar, craniocervical traction, a halo, a rotating frame, or rocking bed (Fig. 60-6).

Surgery

Atlanto-axial (C1–2)

In the cervical spine, open-mouth odontoid films are used to demonstrate the relationship of the lateral masses of C1 with the articular pillars of C2. The “rule of Spence” states that if the sum of the overhang of both C1 lateral masses on C2 is greater than 7 mm, then the transverse ligament is likely disrupted, resulting in C1–2 instability. Treatment typically involves halo vest immobilization or occipitocervical fusion (see Fig. 60-4).

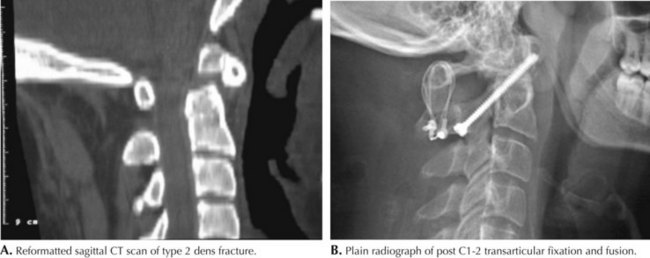

Dens fractures are subclassified (see Fig. 60-4). Type 1 fractures occur through the tip of the dens above the transverse ligament. They are quite rare and may be associated with atlantoaxial instability, necessitating arthrodesis. Type 2 fractures, the most common, occur through the base of the dens and are usually unstable (Figs. 60-4 and 60-6).

There is considerable controversy regarding treatment. The primary indications for surgery include a displacement of the dens greater than 6 mm, instability in a halo, and painful non-union. Otherwise, this treatment consists of immobilization in a halo or hard cervical collar. Type 3 fractures occur through the body of C2 and are usually stable, healing with immobilization in a hard collar or halo vest (see Fig. 60-6).

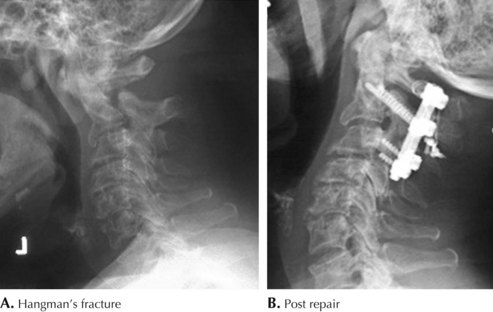

Traumatic spondylolisthesis of the axis caused by bilateral fractures of the C2 pars interarticularis is known as “hangman’s fracture.” Judicial hangings (executions) caused injury by hyperextension and distraction (Fig. 60-8). Today these injuries are caused by hyperextension and axial loading.

Subaxial Cervical Spine

Subluxation is defined by neutral spinal radiographs demonstrating instability with greater than 3.5 mm or angulation greater than 11 degrees. Injuries resulting in stable fractures usually heal well with immobilization in hard collar or halo. Grossly unstable injuries require surgical stabilization (see Fig. 60-8, Fig. 60-9).

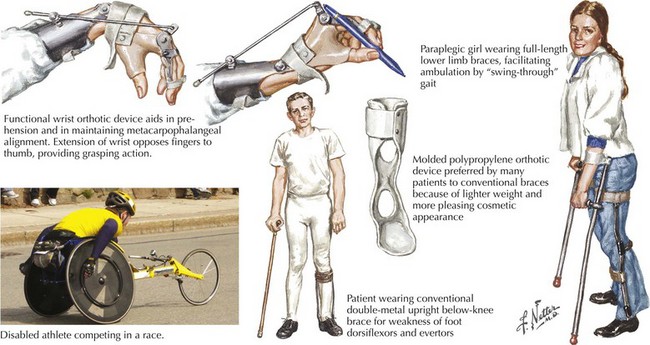

Prognosis

Fortunately, patients with TSCI now have many entrees back into a normal life. Many hold full-time jobs, including being teachers, physicians, or attorneys (Fig. 60-11). They can marry and have children as better understanding of sexual function in the spinal injury patient has led to excellent counseling and means to perform adequately in this setting. Lastly many athletic endeavors are now available as best exemplified by the many wheelchair participants in the marathon (see Fig. 60-11).

Agarwal NK, Mathur N. Deep vein thrombosis in acute spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2009;47:769-772.

Eyster EF, Watts C. An Update of the National Head and Spinal Cord Injury Prevention Program of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons and the Congress of Neurological Surgeons. Clinical Neurosurgery. 1992;38:252-260.

Groopman J. The Reeve Effect. The New Yorker. Nov 10, 2003:82-93.

Hadley MN, Argires PJ. The acute/emergent management of vertebral column fracture-dislocation injuries. Neurosurgical Emergencies, Volume II, American Association of Neurological Surgeons. 1994:249-262. Chapt 15

Hugenholtz H. Methylprednisolone for acute spinal cord injury: not a standard of care. Canadian Medical Association journal. 2003;168:1145.

Hurlbert RJ. Methylprednisolone for acute spinal cord injury: an inappropriate standard of Care. J Neurosurgery. 2000;93(Suppl. 1):1-7.

Kim SU, de Vellis J. Stem cell-based cell therapy in neurological diseases: A review. J Neurosci Res. 2009;87:2183-2200.

Lo B, Parham L. Ethical issues in stem cell research. Endocr Rev. 2009;30:204-213.