8 Trauma Resuscitation

• The approach to trauma resuscitation is based on the assumption that all severely injured patients can initially be evaluated and treated with the same set of guidelines.

• Regardless of the specific injury, these guidelines focus on the broader concept of sustaining life by maximizing oxygenation, ventilation, and perfusion—the ABCs of trauma resuscitation.

Epidemiology

Traumatic injury is a significant cause of death and disability worldwide, especially in the younger population. In the United States, unintentional injury is the leading cause of death in the age range between 1 and 44 years.1 Approximately half of trauma-related deaths occur at the time of injury or before the patient reaches the hospital. Another 30% of traumatic deaths may occur in the first few hours after the event. It is this severely injured, but salvageable population that should be immediately evaluated and treated with the trauma resuscitation paradigm.

Perspective

Shock in trauma patients is often due to hemorrhagic blood loss, but it may also be caused by damage to the heart, great vessels, or lungs or by hemodynamic compromise from fat emboli, ischemia, or neurogenic shock (Box 8.1).

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The American College of Surgeons and many emergency medical service systems have adopted algorithms based on clinical signs and symptoms for transport to a trauma center.2 These signs and symptoms identify patients at high risk for injury and are based on early physiologic changes, anatomic criteria, or a mechanism with a high likelihood of significant injury (Box 8.2). Along with the trauma center criteria, in each of the major anatomic areas there are important clues to potentially life- and limb-threatening injures (Table 8.1).

Box 8.2 Criteria for the Identification of Traumatized Patients with a High Probability of Injury Requiring Transport to a Trauma Center

Mechanism of Injury

| ANATOMIC AREA | MOST THREATENING SIGNS |

|---|---|

| Head | Cerebrospinal fluid leak |

| Raccoon eyes | |

| Battle sign | |

| Hemotympanum | |

| Anisocoria | |

| Neck | Expanding hematoma |

| Thrill or murmur | |

| Subcutaneous air | |

| Trachea deviated from midline | |

| Pulsatile hemorrhage | |

| Spine | Paralysis |

| Paresthesias | |

| Decreased rectal tone | |

| Chest | Subcutaneous air |

| Multiple rib fractures | |

| Sucking chest wound | |

| Asymmetric chest rise | |

| Abdomen | Abdominal wall bruising |

| Distended abdomen | |

| Pelvis | Unstable pelvis |

| Large expanding hematoma | |

| Blood at urethral meatus | |

| Scrotal hematoma | |

| Bone fragments in vaginal vault or rectum | |

| High-riding prostate | |

| Extremities | Pallor |

| Decrease in or absence of pulses | |

| Weakness or paralysis |

Head injuries may result in a decreased level of consciousness leading to loss of airway protection or respiratory drive. Head injuries can also precipitate hemorrhagic shock as a result of the abundant vascular supply of the face and scalp. Because of their proportionally larger heads, children can lose a significant amount of blood with closed intracranial hemorrhage. For further specific evaluation and treatment of head injuries, see Chapter 73.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Primary Survey

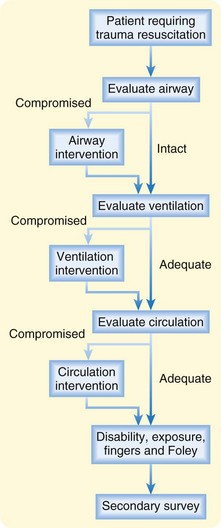

Although performance of the primary survey should be fluid and may involve multiple individuals performing multiple actions simultaneously, the components of the primary survey can be broken down into six sequential steps: airway, breathing, circulation, disability, exposure, and fingers or Foley (ABCDEF) (see Fig. 8-1 and Priority Actions box).

If an indication for intervention is discovered during the primary survey, treatment should be initiated and the primary survey restarted from the beginning (Fig. 8.2).

The next step is a brief neurologic examination (for disability—D). At this point, assessment for disability does not include a detailed neurologic examination but instead a look at the gross motor movement of all extremities and the patient’s level of alertness. The most common tool for evaluating global neurologic function is the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) (Table 8.2).3 Three systems are evaluated: eye opening, verbal response, and motor response. The closer that each function is to baseline, the higher the score for each system. A GCS score of 13 or higher correlates with mild brain injury, 9 to 12 with moderate injury, and 8 or less with severe brain injury. A GCS score lower than 8 is an indication for immediate airway control. Thus, the GCS can help in evaluating the need for intubation, provide a marker for serial neurologic examinations, and promote clear communication with consultants regarding patient status.

| RESPONSE | SCORE |

|---|---|

| Eye Opening | |

| No eye opening | 1 |

| Eye opening to pain | 2 |

| Eye opening to verbal command | 3 |

| Eyes open spontaneously | 4 |

| Verbal | |

| No verbal response | 1 |

| Incomprehensible sounds | 2 |

| Inappropriate words | 3 |

| Patient confused | 4 |

| Patient oriented | 5 |

| Motor | |

| No motor response | 1 |

| Extension to pain | 2 |

| Flexion to pain | 3 |

| Withdrawal from pain | 4 |

| Patient localizes pain | 5 |

| Patient obeys commands | 6 |

* The best of each response is used for the individual score; scores are added for the total Glasgow Coma Scale score.

![]() Priority Actions

Priority Actions

Primary Survey

B = Breathing: Maximize ventilation

C = Circulation: Stabilize hemodynamic status

D = Disability: Evaluate mental status and perform a neurologic examination

E = Exposure: Completely undress and examine the patient

F = Fingers and Foley: Perform orogastric, bladder catheter, vaginal, and rectal examinations

Secondary Survey

In a hypotensive patient, because the abdominal cavity can conceal enough blood to be an immediate threat to life, part of the secondary survey is the focused abdominal sonography examination for trauma (FAST). FAST can be done in the resuscitation area. Because it is faster and less invasive to obtain, FAST has replaced diagnostic peritoneal lavage (Table 8.3).4,5 Likewise, the more sensitive and specific computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen should wait until the end of the secondary survey because CT scanning may be time-consuming and takes the patient out of the resuscitation area.6

| MODALITY | ADVANTAGES | DISADVANTAGES |

|---|---|---|

| Radiographs | Inexpensive Easy to obtain and read Good for identification of foreign objects and projectiles May be useful as screening for free air before DPL |

Very low sensitivity and specificity for injury in patients with blunt abdominal trauma |

| Computed tomography (CT) | High sensitivity High specificity |

Patient has to leave resuscitation area |

| Ultrasonography (US) | Easy and quick | Operator dependent Variable sensitivity and specificity for organ injury |

| Diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) | High sensitivity High specificity |

Operator dependent Time-consuming More invasive than CT or US Significant complications (perforated bowel, bleeding, infection) |

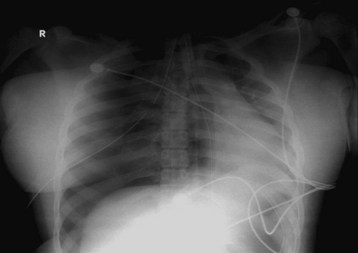

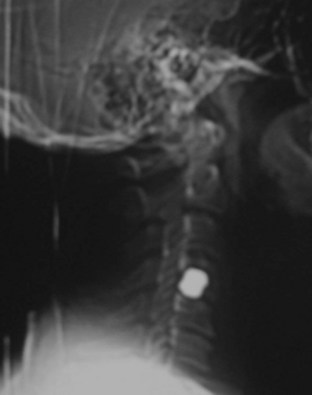

For many years, standard trauma series radiographs included plain films of the cervical spine, the chest, and the pelvis. Currently, the only standard plain film is the chest radiograph. The cervical spine radiograph has been replaced by CT of the cervical spine, but a rare exception is the use of screening films for penetrating trauma (Fig. 8.3). In the majority of trauma patients, the pelvic radiograph has been replaced by CT of the abdomen and pelvis with reconstructed images of the bony pelvis. In some patients, such as those who may need immediate pelvic binding to temporize hemorrhage or penetrating injury to the pelvis, a one-view pelvic radiograph in the trauma suite is still useful. Thus, the new standard trauma radiology series involves a chest radiograph and CT scans of the head, cervical spine, and abdomen and pelvis.7 Chest CT is indicated for a widened mediastinum or if vascular injury is suspected. Early consideration of the need for CT angiography of the neck or extremities should be undertaken to minimize the load of contrast media.

Blood specimens for laboratory studies may be drawn during the initiation of intravenous (IV) access in the primary survey or can be obtained during the secondary survey. Laboratory tests should include a complete blood count, serum chemical analysis, coagulation studies (prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time), and urinalysis. Two immediately available studies are the urine pregnancy test and fingerstick serum glucose measurement, and the results of either test can significantly change the course of the resuscitation. In the setting of altered mental status, a blood alcohol measurement and toxicology screen may also be useful. The serum lactate level can be monitored as a marker of tissue perfusion.8,9

After the primary and secondary surveys are completed and the patient is sufficiently resuscitated, the evaluation and treatment plan takes on a much more individualized course.10

Special Circumstances

Depending on the specific patient’s findings,11 injuries, underlying diseases, and age, each injury may necessitate further radiologic studies (Table 8.4), observation, or surgical intervention.

Table 8.4 Additional Studies in Trauma Patients Dictated by Special Circumstances

| TRAUMA PRESENTATION | ADDITIONAL STUDIES |

|---|---|

| Altered mental status, head trauma | Head computed tomography (CT) |

| Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) | |

| CT angiography of cerebral vascular system | |

| See also Chapter 73 for detailed evaluation of head trauma | |

| Chest wall trauma | Repeated chest radiography |

| Full upright posteroanterior and lateral chest radiographs | |

| CT of the chest | |

| Angiography | |

| MRI of the chest | |

| See also Chapter 78 for detailed evaluation of chest and thoracic trauma | |

| Abdominal trauma | CT of the abdomen |

| Focused abdominal sonographic examination for trauma (FAST) | |

| Diagnostic peritoneal lavage | |

| See also Chapters 79 and 80 for detailed evaluation of abdominal trauma | |

| Pelvis | Retrograde urethrography |

| Cystography | |

| CT of the abdomen and pelvis | |

| Extremity | Angiography |

| Neck, back, spine | CT or MRI of the cervical, thoracic, or lumbar spine |

| Obstetric | Ultrasonography |

| Fetal heart monitoring |

Treatment: Hospital

For a severely injured patient, the primary airway intervention is orotracheal intubation by rapid-sequence induction. Indications for airway intervention include airway protection, expected clinical course, and the need for assisted ventilation or oxygenation (Box 8.3).

After the airway is controlled, respiratory status is evaluated. Several alterations in ventilation mandate immediate intervention (Table 8.5).

Table 8.5 Indications for Respiratory Intervention in Patients with Trauma

| INDICATION | INTERVENTION |

|---|---|

| Tension pneumothorax | Needle decompression |

| Pneumothorax and hemothorax | Tube thoracostomy |

| Sucking chest wound | Tube thoracostomy, petroleum jelly (Vaseline) compression dressing |

| Pulmonary contusion with hypoxia | Intubation |

After the airway and breathing are evaluated and stabilized, hemodynamic status should be evaluated. During trauma resuscitation, it is imperative that IV access be established immediately to facilitate rapid transfusion or administration of blood products (18-gauge or larger IV line). Ideal guidelines recommend a minimum of two working IV sites. Alternatives to large-bore peripheral IV access are intraosseous lines, central lines, and venous cutdown lines. In a hypotensive adult patient with trauma, an initial bolus of 2 L of warm normal saline or lactated Ringer solution is a reasonable starting point. In children, a 20-mL/kg bolus should be used. If the traumatized patient remains hypotensive after the initial bolus, transfusion of type O-negative or type-specific blood should be considered. A caveat to this statement is a patient who has sustained penetrating trauma to the chest or abdomen, in whom a short period of permissive hypotension (on the way to the operating room) may improve survivability by not disrupting an internal tamponade.5 Recent military and trauma center practice has championed aggressive blood and fresh frozen plasma resuscitation in a 1 : 1 ratio in patients in hemorrhagic shock. When possible, manual pressure or military tourniquets should be used in conjunction with fluid or blood resuscitation to temporize hemorrhage.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

All patients requiring trauma evaluation and treatment because of anatomic or physiologic trauma center criteria (see Box 8.2) must be admitted to the hospital. Patients who meet the mechanism criteria only and in whom thorough evaluation identifies no injuries may be candidates for discharge with careful warnings and comprehensive discharge planning.

![]() Documentation

Documentation

History

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Recovery from injuries takes time and frequently extensive rehabilitation.

Recidivism for certain injuries is common; consider referrals to specific programs according to circumstances.

Discuss prevention of further injury, wound care, cast care, and so on.

Alert the patient to warning signs for which immediate care should be sought.

American College of Surgeons. Advanced trauma life support program for doctors, 8th ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2008.

Asimos AW, Gibbs MA, Marx JA, et al. Value of point of care blood testing in emergent trauma management. J Trauma. 2000;24:1101–1108.

Branney S, Moore EE, Cantrill SV, et al. Ultrasound based key clinical pathway reduces the use of hospital resources for the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1997;42:1086–1090.

Lavery RF, Livingston DH, Tortella BJ, et al. The utility of venous lactate to triage injured patients in the trauma center. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:656–664.

Salim A, Sangthong B, Martin M, et al. Whole body imaging in blunt multisystem trauma patients without obvious signs of injury: results of a prospective study. Arch Surg. 2006;141:468–473.

1 . WISQARS Leading Causes of Death Reports, 1999-2003. Available at http://webapp.cdc.gov/sasweb/ncipc/leadcaus10.html/

2 American College of Surgeons. Advanced Trauma Life Support Program for Doctors, 8th ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 2008.

3 Teasdale G, Jennett B. Assessment of coma and impaired consciousness: a practical scale. Lancet. 1974;2:81–94.

4 Blaivas M, Lyon M, Brannam L, et al. Bedside emergency ultrasonographic diagnosis of diaphragmatic rupture in blunt abdominal trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:601–604.

5 Branney S, Moore EE, Cantrill SV, et al. Ultrasound based key clinical pathway reduces the use of hospital resources for the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1997;42:1086–1090.

6 Grieshop N, Jacobson LE, Gomez GA, et al. Selective use of computed tomography and diagnostic peritoneal lavage in blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma. 1995;38:727–731.

7 Salim A, Sangthong B, Martin M, et al. Whole body imaging in blunt multisystem trauma patients without obvious signs of injury: results of a prospective study. Arch Surg. 2006;141:468–473.

8 Asimos AW, Gibbs MA, Marx JA, et al. Value of point of care blood testing in emergent trauma management. J Trauma. 2000;24:1101–1108.

9 Lavery RF, Livingston DH, Tortella BJ, et al. The utility of venous lactate to triage injured patients in the trauma center. J Am Coll Surg. 2000;190:656–664.

10 Giannoudis PV. Surgical priorities in damage control in polytrauma. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:478–483.

11 Shah AJ, Kilcline BA. Trauma in pregnancy. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:615–629.