Chapter 46 Translabyrinthine Approach to Vestibular Schwannomas

Vestibular schwannomas can be surgically accessed via a subtemporal, a translabyrinthine, or a suboccipital and retrosigmoid approach.1,2 The number of centers that have mastered all approaches has increased. The translabyrinthine approach was reintroduced approximately 35 years ago3 and is successfully used by several otologic specialist centers.4–6 After developments in skull base surgery, neurosurgeons have become aware of the advantages of the translabyrinthine approach for vestibular schwannomas and for other skull base lesions.

Advantages of the Translabyrinthine Approach

It has been stated that the usefulness of the translabyrinthine approach is limited to small tumors. In fact, no tumor is too large to be approached by the translabyrinthine route.7–9 In large and giant tumors, it is a significant advantage to be able to go directly to the center of the tumor; after debulking the center of the tumor, the neoplasm collapses and is displaced toward the opening by the surrounding brain structure.

Disadvantages of the Translabyrinthine Approach

The translabyrinthine procedure destroys the labyrinth and, as a consequence, hearing. This approach is not used if preservation of hearing is attempted. Only a limited number of patients with vestibular schwannomas have hearing worth preserving, however. If the tumor exceeds 2 cm in size, the chances of preserving hearing are known to be poor.10

Surgical Anatomy

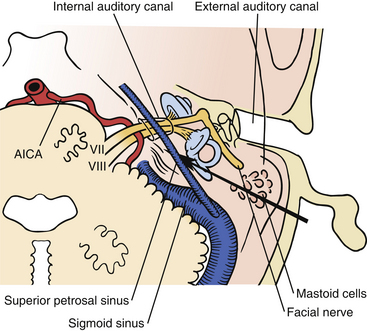

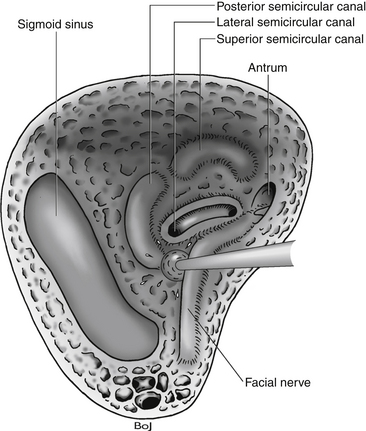

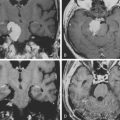

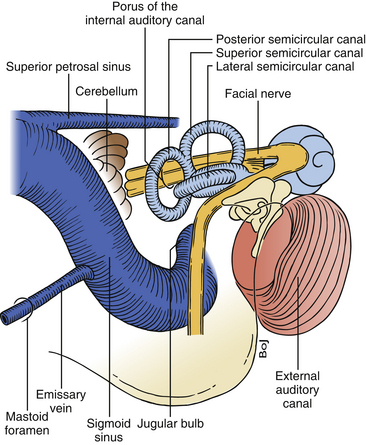

The bone opening for the translabyrinthine approach is done in the mastoid part of the temporal bone (Fig. 46-1). The mastoid is filled with air cells, and the air cells are connected to the middle ear through the tympanic antrum. In the translabyrinthine approach, the bone is removed between the sigmoid sinus and the external ear canal. The sigmoid sinus is located in the sigmoid sulcus in the temporal bone. From the posterior aspect of the sigmoid sinus, emissary veins run through the mastoid foramen to subgaleal veins.11–13

Removing the air cells creates a space that is bounded posteriorly by the wall of the sigmoid sulcus, superiorly by the tegmen tympani, and anteriorly by the prominence of the lateral semicircular canal. Above the prominence of the lateral semicircular canal, the antrum communicates with the tympanic cavity. The facial canal runs close to the mastoid wall of the tympanic cavity. The genu of the facial canal is just inferior to the lateral semicircular canal, and it continues inferiorly to emerge below the skull base at the stylomastoid foramen (Fig. 46-2). The sigmoid sulcus meets the roof of the cavity at a sharp sinodural angle from which the superior petrosal sulcus runs anteriorly. When removing the bone in the sinodural angle, the superior petrosal sinus is exposed in a dural duplex.

FIGURE 46-2 Relationship of the labyrinth, the internal acoustic canal, the facial nerve, and the sigmoid sinus.

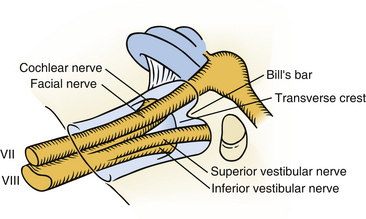

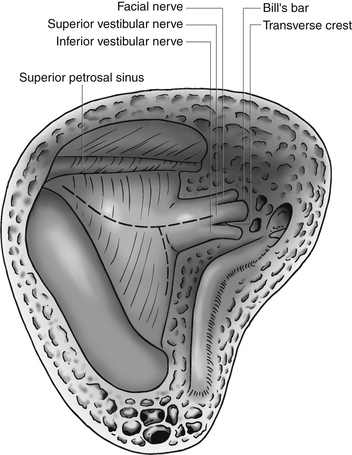

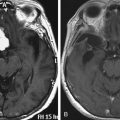

The lateral semicircular canal is an important landmark for the location of the entire labyrinth. After removing all three semicircular canals, the vestibule is open. The vestibule is the bone cavity that harbors the soft-tissue part of the labyrinth utricle and saccule. Through the aperture of the vestibular aqueduct runs the endolymphatic duct that connects the utricle to the endolymphatic sac. The internal auditory canal contains four separate nerves: two vestibular nerves, the facial nerve, and the cochlear nerve. Located laterally are the superior and inferior vestibular nerves separated at the fundus by a bony crest called the transverse crest. Anterior to the superior vestibular nerve, the facial nerve enters the fallopian canal. Laterally, the facial nerve is separated from the superior vestibular nerve by a small vertical bony septum called the vertical crest or Bill’s bar (Fig. 46-3).

Preparation for Surgery

A cephalosporin is given intravenously just before surgery and repeated every 3 hours. The patient is placed in a supine position on the operating table. The patient’s head is turned toward the opposite side and maintained in position with a Sugita head frame. Excessive rotation of the head should be avoided because it may cause venous obstruction in the neck. Decreased mobility of the neck in elderly patients may make sufficient rotation of the head difficult to achieve. This problem may be solved by lifting the ipsilateral shoulder with a pillow and by rotating the whole table.

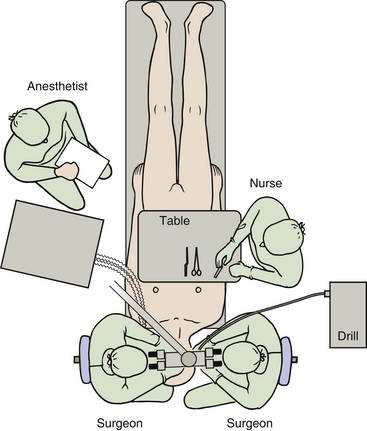

Continuous electrophysiologic monitoring of facial nerve function is performed during the operation.14–16 This monitoring has become an established procedure and is mandatory in my operations. To accomplish this, electrodes are placed in the frontal and oral orbicular muscles. We use a floor-standing operating microscope with the two surgeons sitting opposite each other on each side of the patient’s head. This setup enables both surgeons to be in a comfortable sitting position with a direct view in the microscope. The lead surgeon sits on the same side as the tumor. In left-sided tumors, the drill is placed between the two surgeons, and in right-sided tumors, the drill is placed between the scrub nurse and the surgeon on the right side (Fig. 46-4). The anesthesiologist is placed at the lower left side of the table at the level of the hip of the patient.

Surgical Procedure

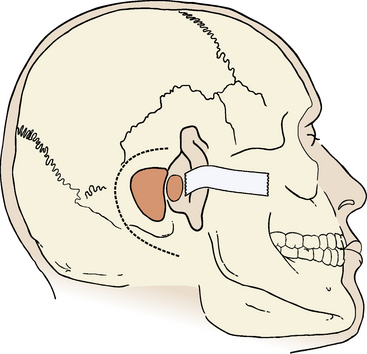

Although some surgeons advocate routine cannulation of the lateral ventricle to relieve hydrocephalus or prevent surgically induced hydrocephalus, I do not find this necessary because, even in large tumors, it is easy to access the cistern magna beneath the tumor, open the arachnoid, and allow cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to drain. The skin incision is made using the cutting cautery to decrease the amount of bleeding from the skin. The incision starts at the upper edge of the helix, superior to the linea temporalis; it continues 4 to 5 cm posteriorly, turns inferiorly, and ends near the tip of the mastoid process (Fig. 46-5).

Mastoidectomy

An extended mastoidectomy is performed with removal of bone over the sigmoid sinus and the middle cranial fossa (Fig. 46-5). In cases with an anteriorly placed sigmoid sinus or large tumors, I also remove bone over the posterior cranial fossa behind the sigmoid sinus.17,18 The extended bone removal ensures good visualization of the entire surgical field. The power drill, driven by either an electric motor or an air turbine, is an essential tool in the translabyrinthine procedure. The cortical bone covering the mastoid region is removed by a large cutting drill. In cases with pronounced pneumatization, a large hole can be made quickly and safely. The anterior margin for cortical bone removal is just behind the external ear canal. The opening is gradually widened backward to the sigmoid sinus and upward to the dura in the middle cranial fossa. Removal of bone over the sigmoid sinus must be done carefully. If the cutting drill tears the sigmoid sinus, profuse bleeding ensues, requiring packing with Surgicel or direct suture of the sinus wall. Large emissary veins often drain into the posterior aspect of the sigmoid sinus. They can be identified through the bone as it is removed. The emissary veins must be controlled with bipolar coagulation and are filled with bone wax. With a drill, the sigmoid sinus is skeletonized.

The method recommended by House and Hitselberger19 is to leave a small island of bone (Bill’s island) over the sigmoid sinus to protect the surface from the trauma of retraction. With a diamond drill, the bone around the outlined island is removed, leaving a part of the sinus wall with an oval piece of bone. The sinus wall and the bony island can then be depressed, and the sinus wall that corresponds to the bony island is protected. I find this method less appropriate because of the risk of lesions in the sinus wall that may be produced by the sharp edge of the bony island.

Labyrinthectomy

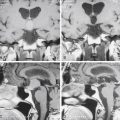

It is essential to open the antrum and to identify the lateral semicircular canal (Fig. 46-6). This canal is a main landmark, and once the positions of this canal and of the antrum are known, the three-dimensional anatomy of the facial nerve is known. After identification of the facial nerve, the labyrinthectomy is performed. The bone in the sinodural angle is removed, followed by opening along the superior petrosal sinus until the labyrinthine bone is encountered. The lateral semicircular canal is drilled away until the ampulla is reached anteriorly. Then the posterior and superior semicircular canals are identified and removed to their entrance in the vestibule. After opening of the vestibule, the facial nerve is skeletonized from the genu inferiorly to near the stylomastoid foramen. It is not necessary to remove all bone around the nerve. I always make a small window in the fallopian canal near the second genu to ensure the position of the nerve and to ensure correct function of the facial nerve monitoring device. To avoid injury to the facial nerve, a thin, eggshell bone is left on the nerve. Only posteriorly, where access is needed to approach the cerebellopontine angle, is the nerve exposed.

Internal Auditory Canal Dissection

All bone between the internal meatus and the jugular bulb is removed. The location of the jugular bulb is extremely variable. When its position is low, all bone removal necessary for tumor removal can be performed without seeing the jugular bulb. In other cases, its position is high and occurs as a bluish spot in the bone after removing the ampulla of the posterior semicircular canal. The surgeon should always be aware of the blue color of the jugular bulb when drilling medial to the facial nerve and inferior to the posterior semicircular canal. All bone covering the jugular bulb must be removed in cases with a high-positioned jugular bulb, in which the bulb is an obstacle to proper bone removal from the inferior aspect of the internal acoustic meatus.

The facial nerve often underlies the dura along the anterior–superior aspect of the internal auditory canal, and extreme care must be taken not to allow the bur to slip into the canal. The facial nerve is especially vulnerable at this point. The lateral end of the internal auditory canal is divided by the transverse crest in an inferior and a superior compartment (Fig. 46-7). The bone around the inferior compartment can be drilled away to the most lateral extent of the canal without risk of facial nerve injury. In the superior compartment, bone removal allows identification of a bar of bone (Bill’s bar), which separates the superior vestibular nerve from the facial nerve. The bone is removed at the porus and the medial part of the internal auditory canal first; the more difficult lateral part is left until last, when most of the bone removal has been completed.

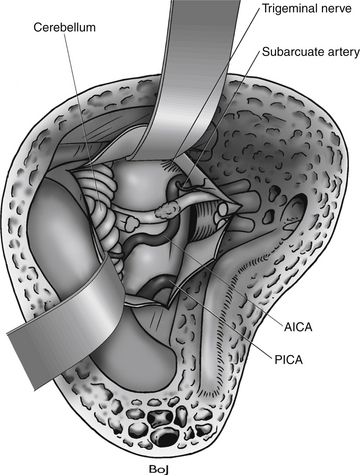

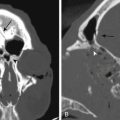

Dural Opening

The dural incision is started superiorly in the sinodural angle near the sigmoid sinus continuing down to the porus (see Fig. 46-7). Care is taken to avoid vessels on the surface of the tumor. Posteriorly, the petrosal vein lies just beneath the dura. This vein originates in the cerebellum and drains into the superior petrosal sinus near the level of the internal auditory canal. If the dura is pulled laterally with a small hook, the space between the cerebellum and the dura is enlarged, and injury to the vessels may be avoided. At the porus, a small incision is made on both sides of the porus. Around the porus, the dura often forms a distinct constriction ring that usually adheres to the surface of the tumor, and there are small vessels going from the dura to the tumor. The dural ring must be divided, and a further incision is made over the dura in the meatus. In the meatus, the dura is often extremely thin, and sometimes it is opened while removing the bone around the meatus. The small vessels in the thickened dura at the porus can be coagulated with bipolar coagulation. Cottonoids are advanced into the plane between the tumor and the cerebellum. The surgeon must develop this plane accurately, because doing so separates the major vessels of the cerebellopontine angle from the tumor. To widen the opening, retractors are attached to the Sugita head frame and placed on the dura of the middle fossa and on a cottonoid on the cerebellum and the sigmoid sinus.

Identification of the Facial Nerve in the Fundus of the Internal Auditory Canal

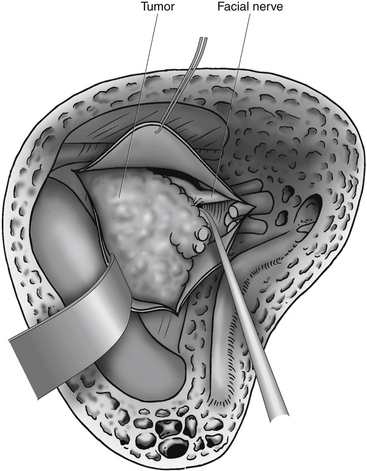

In the remaining cases, the fundus of the internal auditory canal is filled with tumor, and identification of the facial nerve is more difficult. During bone removal, the medial part of the fallopian canal is opened, which uncovers a labyrinthine segment of the facial nerve. Bill’s bar separates the facial nerve anteriorly from the superior vestibular nerve. A fine hook is inserted lateral to Bill’s bar and gently placed beneath the superior vestibular nerve and Bill’s bar. The superior vestibular nerve can then be pulled out from its canal. Likewise, the two nerves inferior to the transverse crest (the inferior vestibular nerve and the cochlear nerve) are pulled out from their canals, along with the tumor (Fig. 46-8). Positive identification of the facial nerve at the lateral end of the internal auditory canal is one of the principal advantages of the translabyrinthine approach.

Freeing the Tumor from the Facial Nerve in the Internal Auditory Canal

The arachnoid sheath completely surrounds the tumor, nerves, and vessels in the meatus, and the arachnoid strands that attach the facial nerve to the tumor must be divided. The meatal part of the tumor is gently retracted backward. Small hooks or fine microscissors are used to free the facial nerve from the arachnoid fibers that bind the nerve to the tumor. Because cutting of the arachnoid occurs along the facial nerve, the surgeon must have identified the inferior and the superior edges of the nerve accurately. Usually, it is relatively easy to develop the dissection plane between the facial nerve and the tumor in the internal auditory canal, but difficulties often arise at the porus. Around the entire circumference of the porus, dural adhesions to the tumor make dissection of the facial nerve from the tumor difficult. The exact position of the facial nerve in the porus must be established before the adhesions between the dura and the tumor are removed. Inferiorly, freeing of the tumor from the porus is simpler because damage to the cochlear nerve is insignificant. Superiorly, the facial nerve may be at risk. At times, it is difficult to isolate the facial nerve at the porus. In these cases, it is wise to carry out a partial tumor removal, identify the facial nerve medially, and follow the nerve laterally until the porus is reached. During this work, the surgeon must be careful not to push the tumor forward or medially, because stretching the facial nerve, especially at the porus level, can damage the nerve. Early mobilization of the tumor from the internal auditory canal has the advantage that the landmarks are well defined and are not obscured with blood, as tends to happen later in the surgical dissection.

Tumor Removal

Inferior Dissection

Dissection at the inferior aspect of the tumor usually leads into the large cerebellomedullary cistern, which allows CSF to escape. This step improves the operative condition, and if any difficulties are encountered because of lack of room in the posterior fossa, draining the cerebellomedullary cistern as soon as possible is valuable.

Anterior Dissection and Final Tumor Removal

In large tumors, the dissection of the facial nerve is done in an anterior–posterior direction. The small portion of tumor that covers the facial nerve from the brain stem to the porus is the most difficult to remove (Fig. 46-9). The anterior part of the tumor capsule usually contains a number of small vessels from arteries and vein, and dissection can easily provoke bleeding. Veins are often present around the facial nerve’s entry zone from the brain stem. Coagulation of the bleeding vessels is dangerous and must be precise to avoid facial nerve injury.

• The facial nerve is often stretched and spread out over the largest prominence of the tumor, which sometimes makes the nerve nearly invisible.

• The facial nerve is not protected by an epineurium and is vulnerable to injury.

• At the porus, the facial nerve is often embedded in the tumor capsule, causing problems when loosening the tumor.

Care must be taken not to leave fragments of tumor on the nerve, because the dissection continues inside the tumor and obscures the location of the nerve, which may be lost.

Facial Nerve Repair

If the nerve has been divided during operation, the surgeon may get an acceptable level of function by anastomosing the nerve ends, provided that the central stump can be found and isolated. If the nerve ends can reach each other, they are anastomosed end to end and fixed with a suture and fibrin glue.20–22 If a gap exists, a great auricular nerve or sural nerve graft is used to bridge the gap between the nerve ends.

Postoperative Management and Complications

Surgery on large tumors in the posterior fossa is not without risks.23–25 Large tumors sometimes adhere strongly to the surface of the cerebellum and the brain stem. Dissection of the tumor from the surroundings may elicit cerebellar edema and infarction. Veins can often be coagulated, but sometimes packing is necessary, especially of the bulb of the sigmoid sinus and the petrosal vein. Hematomas or reactive edema of the cerebellum may necessitate immediate response. Close observation of the patient is necessary in the initial postoperative phase by trained nurses in the intensive care unit. Acute hydrocephalus resulting from obstruction of CSF drainage from the ventricles may occur because of edema or hematoma at the level of the fourth ventricle.

Hematoma

Postoperative hematoma after a translabyrinthine approach is a rare but serious complication. This complication is the cause of most of the mortality seen after translabyrinthine removal of vestibular schwannomas. Even when excellent hemostasis appears to have been achieved, however, postoperative hemorrhage may occur,26 and it seems most likely among elderly patients and patients with large tumors. The hematoma is most likely to occur shortly after the operation but may be seen days after surgery.

Facial Paralysis

Even though the nerve seems anatomically intact at the end of the operation, some patients exhibit postoperative facial paralysis. These patients still have a good chance for some function of the facial nerve. At least 6 months of observation should be allowed before any further treatment is considered. If permanent facial paralysis exists, a faciohypoglossal anastomosis is carried out after a delay of approximately 1 year.27

CSF Leakage

CSF leakage is a common complication after vestibular schwannoma surgery,28 and it is seen in 5% to 15% of the cases. The leakage may occur either through the skin at the wound site or through the nose. Rhinorrhea is more common than leakage through the wound. The diagnosis of postoperative CSF rhinorrhea is often obvious within a few days of surgery, but its recognition may be delayed. Some patients report only a sensation of postnasal dripping or a salty taste in the mouth. In these cases, the diagnosis may be subtle. The patient should be tested in a head-down position for watery escape from the nose before discharge.

When rhinorrhea is diagnosed, a lumbar drain is inserted for 3 to 5 days; however, the success with CSF drainage is not as high as in the wound leakage, probably because the defect is located in the bone, which is not as easily overgrown as is a defect in soft tissue. If the lumbar drainage fails to close the defect, reoperation and resealing the communication to the middle ear and eustachian tube with muscle graft and bone wax in the communicating air cells is necessary.

Conclusions

The results from translabyrinthine and retrosigmoid approaches are comparable, with less than 1% mortality, 97% total removal, anatomic preservation of facial nerve in 90% to 95% of cases, and a functioning facial nerve in more than 70% of cases 1 year after surgery.4,30–32 Except for hearing preservation, the published results do not favor one method over the other, and preference of one method should be based mostly on personal experience.

Acknowledgment

The author is indebted to Bo Jespersen, MD, who provided all illustrations for this chapter.

Anson B.J., Donaldson J.A. Surgical Anatomy of the Temporal Bone and Ear, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1973.

Barrs D.M., Brackmann D.E., Hitzelberger W.E. Facial nerve anastomosis in the cerebellopontine angle: a review of 24 cases. Am J Otol. 1984;5:269-272.

Benecke J.E. Complications of acoustic tumor surgery and their management. Semin Hear. 1989;10:341-345.

Briggs R.J., Luxford W.M., Atkins J.S.Jr., Hitselberger W.E. Trans-labyrinthine removal of large acoustic neuromas. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:785-790.

Briggs R.J.S., Fabinyi G., Kaye A.H. Current management of acoustic neuromas: review of surgical approaches and outcomes. J Clin Neurosci. 2000;7:521-526.

Day J.D., Chen D.A., Arriaga M. Translabyrinthine approach for acoustic neuroma. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:391-395.

Ebersold M.J., Harner S.G., Beatty C.W., et al. Current results of the retrosigmoid approach to acoustic neurinoma. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:901-909.

Helms J. Indications for the suboccipital, translabyrinthine, and transtemporal approaches in acoustic neuroma surgery. In: Tos M., Thomsen J. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Acoustic Neuroma. Amsterdam: Kugler; 1992:501-502.

House W.F., Hitselberger W.E. Fatalities in acoustic tumor surgery. In: House W.F., Leutje C.M. Acoustic Tumors. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1979:235-264.

House W.F., Hitselberger W.E. Translabyrinthine approach. In: House W.F., Leutje C.M. Acoustic Tumors. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1979:43-87.

House W.F., editor. Monograph. Transtemporal microsurgical removal of acoustic neuromas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1964;80:597-756.

Jackler R.K., Pitts L.H. Selection of surgical approach to acoustic neuroma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1992;25:361-387.

King T.T., Morrison A.W. Translabyrinthine and transtentorial removal of acoustic tumours: results of 150 cases. J Neurosurg. 1980;52:210-216.

Mamikoglu B., Wiet R.J., Esquivel C.R. Translabyrinthine approach for the management of large and giant vestibular schwannomas. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:224-227.

Mass S.C., Wiet R.J., Dinces E. Complications of the translabyrinthine approach for the removal of acoustic neuromas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:801-804.

Rhoton A.L.Jr. Microsurgical anatomy of the brainstem surface facing an acoustic neuroma. Surg Neurol. 1986;25:326-339.

Rhoton A.L.Jr., Tedeschi H. Microsurgical anatomy of acoustic neuroma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1992;25:257-294.

Selesnick S.H., Liu J.C., Jen A., Newman J. The incidence of cerebrospinal fluid leak after vestibular schwannoma surgery. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:387-393.

Slattery W.H.III, Francis S., House K.C. Perioperative morbidity of acoustic neuroma surgery. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:895-902.

Sterkers J.M. Life-threatening complications and severe neurologic sequelae in surgery of acoustic neurinoma. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 1989;106:245-250.

Sterkers J.M., Corlieu C., Sterkers O. Acoustic neuroma surgery (1300 cases), the translabyrinthine method. In: Tos M., Thomsen J. Acoustic Neuroma. Amsterdam: Kugler; 1992:377-378.

Thomsen J., Tos M., Børgesen S.E., Møller H. Surgical results after removal of 504 acoustic neuromas. In: Tos M., Thomsen J. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Acoustic Neuroma. Amsterdam: Kugler; 1992:331-335.

Tos M., Thomsen J., Harmsen A. Results of translabyrinthine removal of 300 acoustic neuromas related to tumour size. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl (Stockh). 1988;452:38-51.

Tos M., Thomsen J. Translabyrinthine Acoustic Neuroma Surgery: A Surgical Manual. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme, 1991.

Yates P.D., Jackler R.K., Satar B., et al. Is it worthwhile to attempt hearing preservation in larger acoustic neuromas? Otol Neurotol. 2003;24:460-464.

1. Helms J. Indications for the suboccipital, translabyrinthine, and transtemporal approaches in acoustic neuroma surgery. In: Tos M., Thomsen J. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Acoustic Neuroma. Amsterdam: Kugler; 1992:501-502.

2. Jackler R.K., Pitts L.H. Selection of surgical approach to acoustic neuroma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1992;25:361-387.

3. House W.F., editor, Monograph. Transtemporal microsurgical removal of acoustic neuromas, Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg, 1964;:597-756 80

4. Sterkers J.M., Corlieu C., Sterkers O. Acoustic neuroma surgery (1300 cases), the translabyrinthine method. In: Tos M., Thomsen J. Acoustic Neuroma. Amsterdam: Kugler; 1992:377-378.

5. Tos M., Thomsen J., Harmsen A. Results of translabyrinthine removal of 300 acoustic neuromas related to tumour size. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl (Stockh). 1988;452:38-51.

6. King T.T., Morrison A.W. Translabyrinthine and transtentorial removal of acoustic tumours: results of 150 cases. J Neurosurg. 1980;52:210-216.

7. Mamikoglu B., Wiet R.J., Esquivel C.R. Translabyrinthine approach for the management of large and giant vestibular schwannomas. Otol Neurotol. 2002;23:224-227.

8. Briggs R.J.S., Fabinyi G., Kaye A.H. Current management of acoustic neuromas: review of surgical approaches and outcomes. J Clin Neurosci. 2000;7:521-526.

9. Briggs R.J., Luxford W.M., Atkins J.S.Jr., Hitselberger W.E. Trans-labyrinthine removal of large acoustic neuromas. Neurosurgery. 1994;34:785-790.

10. Yates P.D., Jackler R.K., Satar B., et al. Is it worthwhile to attempt hearing preservation in larger acoustic neuromas? Otol Neurotol. 2003;24:460-464.

11. Rhoton A.L.Jr. Microsurgical anatomy of the brainstem surface facing an acoustic neuroma. Surg Neurol. 1986;25:326-339.

12. Rhoton A.L.Jr., Tedeschi H. Microsurgical anatomy of acoustic neuroma. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1992;25:257-294.

13. Anson B.J., Donaldson J.A. Surgical Anatomy of the Temporal Bone and Ear, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1973.

14. Hammerschlag P.E., Cohen N.L. Intraoperative monitoring of the facial nerve in acoustic cerebellopontine angle surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;103:681-684.

15. Syms C.A.3rd, House J.R.3rd, Luxford W.M., Brackmann D.E. Preoperative electroneuronography and facial nerve outcome in acoustic neuroma surgery. Am J Otol. 1997;18:401-403.

16. Harner S.G., Daube J.R., Beatty C.W., Ebersold M.J. Intraoperative monitoring of the facial nerve. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:209-212.

17. Day J.D., Chen D.A., Arriaga M. Translabyrinthine approach for acoustic neuroma. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:391-395.

18. Tos M., Thomsen J. Translabyrinthine Acoustic Neuroma Surgery: A Surgical Manual. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme, 1991.

19. House W.F., Hitselberger W.E. Translabyrinthine approach. In: House W.F., Leutje C.M. Acoustic Tumors. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1979:43-87.

20. Barrs D.M., Brackmann D.E., Hitzelberger W.E. Facial nerve anastomosis in the cerebellopontine angle: a review of 24 cases. Am J Otol. 1984;5:269-272.

21. Fisch U., Dobie R.A., Gmur A., Felix H. Intracranial facial nerve anastomosis. Am J Otol. 1987;8:23-29.

22. Luetje C.M., Whittaker C.K. The benefits of VII-XII neuroanastomosis in acoustic tumor surgery. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:1273-1275.

23. Benecke J.E. Complications of acoustic tumor surgery and their management. Semin Hear. 1989;10:341-345.

24. Sterkers J.M. Life-threatening complications and severe neurologic sequelae in surgery of acoustic neurinoma. Ann Otolaryngol Chir Cervicofac. 1989;106:245-250.

25. Slattery W.H.III, Francis S., House K.C. Perioperative morbidity of acoustic neuroma surgery. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:895-902.

26. House W.F., Hitselberger W.E. Fatalities in acoustic tumor surgery. In: House W.F., Leutje C.M. Acoustic Tumors. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1979:235-264.

27. Ebersold M.J., Quast L.M. Long-term results of spinal accessory nerve–facial nerve anastomosis. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:51-54.

28. Selesnick S.H., Liu J.C., Jen A., Newman J. The incidence of cerebrospinal fluid leak after vestibular schwannoma surgery. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:387-393.

29. Ross D., Rosegay H., Pons V. Differentiation of aseptic and bacterial meningitis in postoperative neurosurgical patients. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:669-674.

30. Ebersold M.J., Harner S.G., Beatty C.W., et al. Current results of the retrosigmoid approach to acoustic neurinoma. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:901-909.

31. Mass S.C., Wiet R.J., Dinces E. Complications of the translabyrinthine approach for the removal of acoustic neuromas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125:801-804.

32. Thomsen J., Tos M., Børgesen S.E., Møller H. Surgical results after removal of 504 acoustic neuromas. In: Tos M., Thomsen J. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Acoustic Neuroma. Amsterdam: Kugler; 1992:331-335.