CHAPTER 59 Total Elbow Arthroplasty for Distal Humerus Nonunion and Dysfunctional Instability

INTRODUCTION

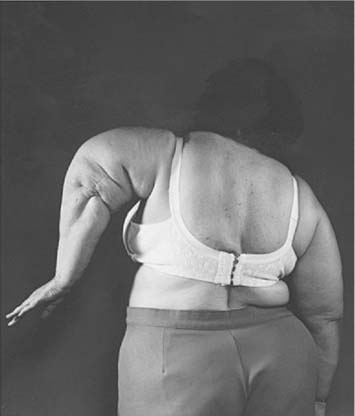

Dysfunctional elbow instability may be defined as a condition in which the elbow joint has lost its fulcrum properties and is no longer able to provide enough support for the hand to be functionally controlled in space (Fig. 59-1).10 In the most extreme circumstances, destruction of the elbow leads to a flail extremity. In less severe cases, stability may be maintained with the arm adducted against the body, but not in other positions (Fig. 59-2). This condition may result from situations such as distal humerus nonunion, severe rheumatoid destruction of the humerus, extensive post-traumatic bone loss, and bone resection for the treatment of deep infection or tumors. Linked elbow arthroplasty provides a dramatic improvement in the function and quality of life of these patients, but the improvements need to be balanced against the risk of complications and mechanical failure.

ELBOW ARTHROPLASTY FOR DISTAL HUMERUS NONUNION

As noted in Chapter 23, nonunion is one of the most challenging complications of distal humerus fractures. Internal fixation is the treatment of choice whenever possible. Modern series have reported a high union rate when internal fixation is used, but the reoperation rate has remained high and function is not always re-established.6,11 Total elbow arthroplasty is an excellent surgical alternative for the salvage of distal humerus nonunions when fixation is considered to be impractical or expected to be associated with a high rate of failure.

RATIONALE, INDICATIONS AND CONTRAINDICATIONS

Joint replacement is a well-accepted treatment modality for fractures in other locations, such as the femoral neck or the proximal humerus. The good track record of some elbow implants for patients with rheumatoid arthritis and other conditions prompted the use of elbow replacement for distal humerus nonunion.5 Elbow arthroplasty is indicated only in a selective group of elderly patients who present with either preexistent symptomatic pathology (for example, a rheumatoid elbow) or low nonunions with substantial osteopenia and severe damage to the articular surface. It is contraindicated in the presence of infection, as well as in nonunions amenable to stable internal fixation and in patients with anticipated high physical demands. An associated nonunion of an olecranon osteotomy complicates the surgical technique but should not be considered a contraindication for the procedure.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

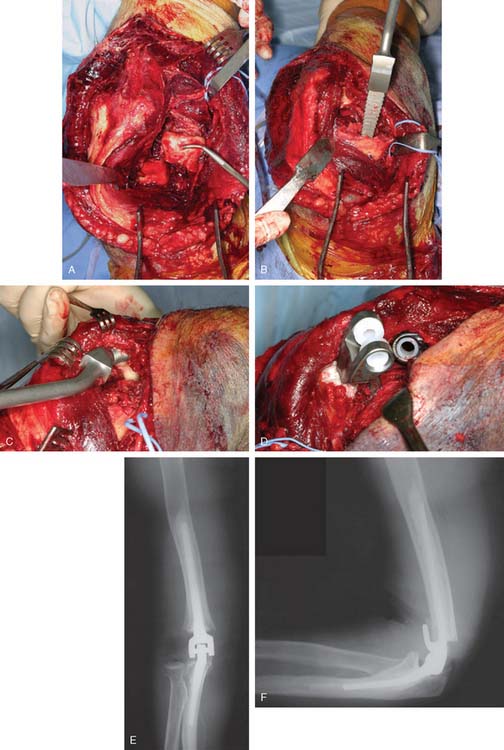

The elbow is exposed through a posterior midline skin incision and the ulnar nerve is identified and treated according to the location of the nerve and preoperative symptoms as mentioned in Chapter 23 on internal fixation for distal humerus nonunions. The extensor mechanism is left undisturbed and the procedure is performed working on both sides of the triceps unless an associated olecranon nonunion, or triceps detachment provides the opportunity for exposure (Fig. 59-3) (see also Chapter 7, Surgical Exposures). Retained hardware is removed, and the nonunited distal humerus is resected subperiosteally and saved for bone grafting behind the flange of the humeral com-ponent. Tissue samples are sent for pathology and microbiology.

The working space created by resection of the distal humerus is ample enough to instrument the canals andimplant the components. The surgical technique for implantation of a linked elbow arthroplasty is detailed in Chapter 52. A capsular release should be associated routinely. Use of a humeral component with an intermediate length stem provides secure fixation. In the presence of severe humeral bone loss, an implant with a longer flange may be cemented proud to make up for part of the lost humeral length (Fig. 59-4). On the contrary, a regular humeral component may be cemented in a deeper position to elevate the joint line and correct flexion contractures. Exposure of the ulnar canal may be improved by partial detachment of the triceps from the olecranon on the medial side. The implants may be fully seated before interlocking, because the articular windows at the medial and lateral side of the elbow after removal of the united distal humerus bone allow interlocking. At the end of the procedure, the common extensor and common flexor muscle groups are sutured to the lateral and medial triceps fascia to seal the joint space and maintain the strength of the forearm muscles.

POSTOPERATIVE MANAGEMENT

After surgery, the elbow is placed in full extension in a bulky dressing with an anterior plaster splint and kept elevated to minimize swelling. Active-assisted range of motion may be initiated on postoperative day one or two. Once the surgical wound is healed, no additiona protection is needed, because the implants are fixed with cement and the extensor mechanism is left completely undisturbed. Usually, patients regain functional elbow motion within the first 3 months after surgery.

OUTCOME

Total elbow arthroplasty has been shown in several studies to provide satisfactory results in a large proportion of well-selected patients. Figgie et al4 reported on 14 patients who received an elbow arthroplasty for the treatment of a distal humerus nonunion. Their mean age was 65 years, and 10 of the 14 patients had previous surgery. At a mean follow-up of 5 years, the mean elbow score improved from 17 to 84 points and there were three failures secondary to dislocation, deep infection, and humeral component loosening. Morrey and Adams9 reported on 36 consecutive patients with an average age of 68 years who underwent total elbow arthroplasty for a distal humerus nonunion. At an average follow-up of 4 years, results were satisfactory in 86% of the patients. There was no or mild pain in 91% and motion was improved in most patients. Complications included deep infection in two cases, polyethylene wear or particulate synovitis requiring surgery in three cases, and transient ulnar neuropathy in two cases.

The Mayo Clinic experience with total elbow arthroplasty for distal humerus nonunions has been updated recently.3 Ninety-two consecutive total elbow arthroplasties performed for the treatment of a distal humeral nonunion were reviewed at an average follow-up of 6.5 years (range, 0.5 to 20.3 years). There were 22 men and 69 women with an average age of 65 years at the time of elbow replacement. Seventy-six elbows (83%) had undergone prior surgery, with an average of two previous operations (range, one to 10). Five elbows had had at least one prior operation due to infection.

Before surgery, 86% of the patients complained of moderate or severe pain. At most recent follow-up, 79% of the patients had no pain or mild pain. Mean extension was improved from 37 to 22 degrees and average flexion from 106 to 135 degrees. Joint stability was restored in all patients, including nine with a grossly flail elbow (Fig. 59-5). Complications included aseptic loosening in 16 (four with periprosthetic fractures), component fracture in five, deep infection in five (three with previous infection), and bushing wear in one patient. At most recent follow-up, 85% of the patients were satisfied with their outcome. Survivorship free or removal or revision for any reason was 95.7% at 2 years, 82.1% at 5 years, 65.3% at 10 and 15 years. The risk of implant failure was increased in patients younger than 65 years old, with two or more prior surgeries, and a history of previous infection.

Some concerns have been raised about the effect of humeral condyle resection on elbow and forearm strength. However, McKee et al8 reported on 32 patients who had undergone total elbow arthroplasty with preservation (16 cases) or resection (16 cases) of the humeral condyles. There were no statistically significant differences in elbow flexion and extension, forearm pronation and supination, or grip strength. Both groups also had similar overall results according to the Mayo elbow performance score.

ELBOW ARTHROPLASTY FOR DYSFUNCTIONAL INSTABILITY

Patients with dysfunctional instability may be offered several treatment options. Some patients with multiple previous surgeries may choose to use a hinged brace and avoid additional procedures. However, most patients are dissatisfied with their use of the arm and wish to explore reconstructive surgery. Surgical options include internal fixation with bone grafting for some distal humerus nonunions, elbow arthrodesis, osteoarticular allografts, or elbow arthroplasty. The advantages and disadvantages of internal fixation for distal humerus nonunions have been discussed in Chapter 23; as noted earlier, elbow arthroplasty represents a better option for the salvage of selected nonunions. Elbow arthrodesis will restore stability; however, a solid fusion may be difficult to achieve in the presence of massive bone loss, and most patients find lack of elbow motion very limiting. Osteoarticular allografts are attractive for the younger patient, but they have been associated with a high rate of complications and graft resorption. Elbow arthroplasty is our treat-ment of choice for many patients with dysfunctional instability.

The primary indication for elbow arthroplasty in this group of patients is instability that prevents useful function of the arm secondary to inability to position the hand in the space (see Figs. 59-1 and 59-2).1,10 Interestingly, many of these patients do not complain of severe pain. Ideally, elbow arthroplasty should be restricted to older patients with low functional demands. However, arthroplasty may be considered for the younger patient with severe bone loss, severe dysfunction, and no other treatment alternatives.

TOTAL ELBOW ARTHROPLASTY IN DYSFUNCTIONAL INSTABILITY: TECHNICAL TIPS

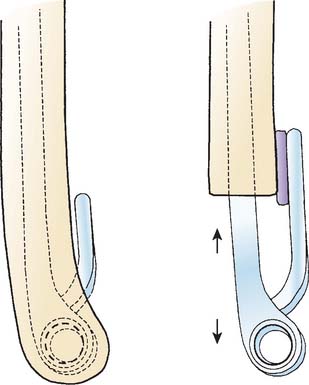

Humeral bone loss in dysfunctional instability can usually be corrected by modifying the depth of insertion of the humeral component, using components with a longer anterior flange in selected cases, and the occasional use of strut grafts (see Fig. 59-4). Most patients with long-standing instability present with shortening of the limb in combination with humeral bone loss. Deeper insertion of the component compensates for the distal bone loss and, at the same time, facilitates achieving more complete elbow extension. Ulnar bone loss can be managed usually by deeper insertion of the ulnar component and the occasional use of strut grafts to reconstruct the olecranon and provide an insertion point and lever arm for the extensor mechanism. In patients with severe shortening, care should be taken to avoid excessive soft-tissue bulk anteriorly in elbow flexion, as this is suspected to facilitate loosening of the ulnar component.2

Adequate balance of the medial and lateral soft tissue structures is necessary to avoid eccentric polyethylene loading. In patients with long-standing dysfunctional instability, the forearm tends to be displaced proximally and to the medial or lateral side of the humerus. When the elbow is realigned and brought to length, the soft tissues on the contracted side may deform the elbow and prevent centralized tracking of the prosthesis. In these circumstances, polyethylene edge-loading may lead to accelerated polyethylene wear (Fig. 59-6).7 Adequate soft tissue releases should be performed whenever possible to achieve a balanced reconstruction.

OUTCOME OF ELBOW ARTHROPLASTY IN DYSFUNCTIONAL INSTABILITY

Ramsey et al10 reported the results of elbow arthroplasty for dysfunctional instability at our institution. Nineteen total elbow arthroplasties performed for the treatment of elbow instability were reviewed at a mean follow-up of 6 years. The underlying pathology responsible for dysfunctional instability included an unstable distal humerus nonunion in 14 patients, severe rheumatoid arthritis in three patients, post-traumatic bone loss in one patient, and bone loss after resection of infected distal humerus in one patient. The main indication for surgery was instability, and pain was not the primary indication for any of the arthroplasties.

1 Baksi D.P. Sloppy hinge prosthetic elbow replacement for post-traumatic ankylosis or instability. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1998;80:614.

2 Cheung E.V., O’Driscoll S.W. Total elbow prosthesis loosening caused by ulnar component pistoning. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2007;89:1269.

3 Cil, A., Veillette, C., Sanchez-Sotelo, J., and Morrey, B. F.: Linked elbow replacement: a salvage procedure for distal humeral nonunion. International Congress on Surgery of the Shoulder (ICSS). Brazil, 2007.

4 Figgie M.P., Inglis A.E., Mow C.S., Figgie H.E.3rd. Salvage of non-union of supracondylar fracture of the humerus by total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1989;71:1058.

5 Gill D.R., Morrey B.F. The Coonrad-Morrey total elbow arthroplasty in patients who have rheumatoid arthritis. A ten to fifteen-year follow-up study. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1998;80:1327.

6 Helfet D.L., Kloen P., Anand N., Rosen H.S. Open reduction and internal fixation of delayed unions and nonunions of fractures of the distal part of the humerus. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2003;85-A:33.

7 Lee B.P., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Polyethylene wear after total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2005;87:1080.

8 McKee M.D., Pugh D.M., Richards R.R., Pedersen E., Jones C., Schemitsch E.H. Effect of humeral condylar resection on strength and functional outcome after semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2003;85-A:802.

9 Morrey B.F., Adams R.A. Semiconstrained elbow replacement for distal humeral nonunion. J. Bone Joint Surg. Br. 1995;77(1):67-72.

10 Ramsey M.L., Adams R.A., Morrey B.F. Instability of the elbow treated with semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1999;81:38.

11 Ring D., Gulotta L., Jupiter J.B. Unstable nonunions of the distal part of the humerus. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 2003;85-A:1040.