CHAPTER 58 Total Elbow Arthroplasty as a Salvage for the Fused Elbow

INTRODUCTION

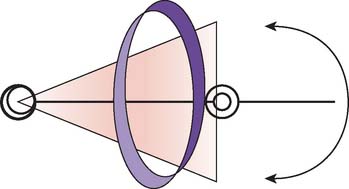

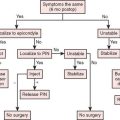

The ankylosed elbow occurs spontaneously or after formal intent. In either instance, the functional outcome is usually not well tolerated. The reason for this is, first, there is no “optimum” position for elbow fusion. The joint is designed to position the hand in space and to one’s self. Second, the other joints compensate poorly for loss of elbow motion. Analysis of compensatory motion after an elbow arthrodesis has documented a compromised ability to complete activities, despite a significantly increased dependence on spine and wrist motion (Fig. 58-1).10 Furthermore, the shoulder plays only a modest role in compensation. For these reasons, there is continued value and interest in managing the stiff elbow by prosthetic replacement. The goal is to attain a functional arc of motion.7

INDICATIONS AND PATIENT SELECTION

The primary goal of total elbow arthroplasty is to restore motion to improvement function. We prefer a patient older than 60 years of age if the pathology follows trauma.8 However, pathologic and functional considerations may prompt replacement at an earlier age, especially in those with inflammatory conditions. Of note is that the extent of comorbidities that tends to exist in these patients further complicates the execution of the procedure.

Radioulnar, radiohumeral, or a combination of these synostoses, with complete loss of forearm rotation, may occur in more than 33% of patients (Fig. 58-2).11 The incidence of additional joint involvement in the ipsilateral and contralateral extremities was 77% and 46%, respectively, in our experience. In fact, in our experience, an isolated elbow fusion occurred in less than 10% of patients.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

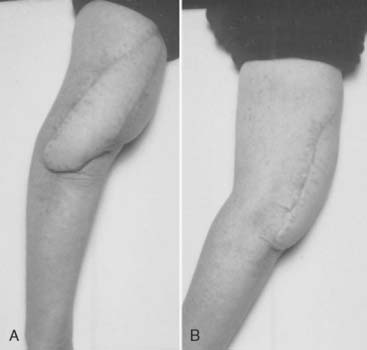

Poor skin coverage is a relative contraindication that can be addressed by soft tissue procedures before the joint replacement (Fig. 58-3). Unwillingness to comply with the 5-kg single event, 1-kg repetitive weight restriction is a reason not to perform total elbow replacement. This implies those involved with heavy use of the extremity such as construction workers should not be offered this operation.

RADIOGRAPHIC EVALUATION

Usually, plane films are adequate. Size and quality of the bone, and angular deformity is noted. We pay close attention to the presence of the olecranon and determine by physical examination if the triceps is attached. The size of the medullary canal and presence and relevance of fixation devices is considered (Fig. 58-4).

EXPECTATIONS

Before surgery, the goals, limitations, and risks are very carefully explained to the patient. Expected outcomes are described based on our experience with approximately 20 cases.5,11

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

Management of the triceps muscle depends upon the integrity of the triceps attachment and status of the distal humerus. If the condyles are present, or if significant contracture of the extensor mechanism exists, then a triceps sparing approach is employed via a technique previously described.1

Determining the axis of rotation of the implant is a key technical consideration, and in most instances, the remnant of the radial head is used as the landmark laterally. Medially, the prominence of the coronoid is employed as the landmark. The osteotomy begins at this level and follows a curved trajectory emerging posteriorly at a level that ensures the triceps attachment is maintained. Meticulous care is taken to recreate or preserve an olecranon process, providing a functional lever arm for the triceps and protecting the skin from erosion by the implant.

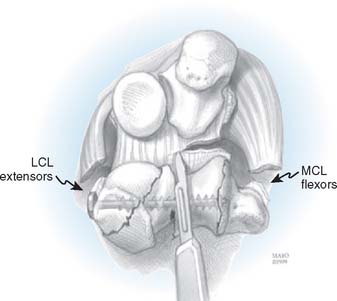

In those instances when the ankylosis or fusion has resulted in malorientation of the forearm referable to the humerus, specific care is taken to release the soft tissue contracture of the flexors and extensors to avoid an imbalance at the articulation (Fig. 58-5). Likewise, accurate positioning of the ulnohumeral implant will avoid excessive wear that otherwise occurs with maloriented components.

POSTOPERATIVE CARE

The elbow is placed in an anterior splint and is elevated overnight. Physical therapists do not participate in the rehabilitation process. A program of static adjustable splinting employs the Mayo Elbow Brace (AirCast DJO, Vista, CA). A permanent lifting restriction of 5 kg is emphasized, and formal strengthening exercises are discouraged. Prophylaxis for heterotopic ossification in the form of single-beam external radiation of 700 cGy is administered to patients with moderate to severe ectopic bone before surgery without postoperative wound complications or rheumatoid disease. Examination under anesthesia for perioperative elbow stiffness is a common adjuvant to our postoperative management.

RESULTS

Small numbers of ankylosed elbows have been included in the reported results of several previous elbow studies. Similar to our experience, Figgie et al.11 reported a mean arc of motion of 80 degrees (35 to 115 degrees) that was maintained for an average of 5 years.2 A 26% complication rate was reported, which was also similar to our experience.

The outcomes, particularly those based on our experience as described below, must be placed in the context of alternative procedures. The only viable one is distraction interposition arthroplasty.6 In our practice, the effectiveness of this procedure for patients with an arc of motion averaging approximately 30 degrees before surgery is approximately 80%.6 The complication rate is similar.

MAYO EXPERIENCE

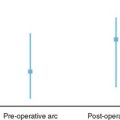

Initial evaluation of efforts to treat the stiff elbow by total elbow arthroplasty was reported by Mansat and Morrey in 2000.5 Fourteen elbows were evaluated a mean of more than 5 years after surgery. The mean preoperative arc averaged 7 degrees, and nine of the 14 elbows were fused. The other five had less than 30 degrees of motion. After the surgery, the mean arc of motion averaged 67 degrees. These authors emphasized the development of ectopic bone around the joint, which was observed to adversely affect outcomes. We also recorded seven complications in five of the 14 patients. These included superficial infection in three, and a deep infection in two. Overall, approximately 78% of patients indicated they were satisfied with the outcome.

RECENT EXPERIENCE

We have recently updated our experience and reported on 13 consecutive patients with complete ankylosis in 13 elbows. All were treated with a linked semiconstrained noncustom total elbow implant (Coonrad-Morrey, Zimmer, Warsaw, IN) (Fig. 58-6).

Only one patient required revision for implant failure due to progressive loosening of a polymethylmethacrylate precoat ulnar component with subsequent fatigue fracture at 5 years, 8 months postoperatively.4 Ectopic ossification was present to varying degrees in four elbows despite the administration of prophylactic external-beam radiation in three of the four.

COMPLICATIONS

The complication rate of total elbow replacement approaches 20% in most series.3,9,12 In our practice, three of the 13 elbows encountered a periprosthetic complication including soft tissue compromise in two and infection in another. One elbow developed skin necrosis requiring débridement and coverage with a myocutaneous latissimus flap. Another elbow required débridement and primary closure for superficial dermal lysis.

1 Bryan R.S., Morrey B.F. Extensive posterior exposure of the elbow. A triceps-sparing approach. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1982;166:188.

2 Figgie M.P., Inglis A.E., Mow C.S., Figgie H.E.3rd. Total elbow arthroplasty for complete ankylosis of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. [Am.]. 1989;71-A:513.

3 Gschwend N., Simmen B.R., Matejovsky Z. Late complications in elbow arthroplasty. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5-2(Pt 1):86.

4 Hildebrand K.A., Patterson S.D., Regan W.D., MacDermid J.C., King G.J. Functional outcome of semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. [Am.]. 2000;82-A:379.

5 Mansat P., Morrey B.F. Semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty for ankylosed and stiff elbows. J. Bone Joint Surg. [Am.]. 2000;82-A:1260.

6 Morrey B.F. Post-traumatic contracture of the elbow. Operative treatment, including distraction arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. [Am.]. 1990;72-A:601.

7 Morrey B.F. Functional evaluation of the elbow. In: Morrey B.F., editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2000:74.

8 Morrey B.F., Adams R.A., Bryan R.S. Total replacement for post-traumatic arthritis of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. [Br.]. 1991;73-B:607.

9 Morrey B.F., Bryan R.S. Complications of total elbow arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1982;170:204.

10 O’Neill O.R., Morrey B.F., Tanaka S., An K.N. Compensatory motion in the upper extremity after elbow arthrodesis. Clin. Orthop. Rel. Res. 1992;281:89.

11 Peden, J. P., and Morrey, B. F.: Total elbow arthroplasty for the management of the ankylosed or fused elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. [Br.] (in press).

12 Voloshin, I., Kakar, S., Kaye, E. K., and Morrey, B. F.: Complications of total elbow replacement: Systematic review of literature in the last decade. (in press).