Chapter 156 To Not Operate

For any new device to become a valuable, viable addition to the surgeon’s armamentarium, it must be either significantly “better” than what it is replacing in some way (e.g., safer, better outcomes, lower failure rate) or equivalent but less expensive.1 Most of the studies published on disc arthroplasty to date have demonstrated equivalence to fusion. However, long-term results and cost analysis are still lacking.

Interestingly, few studies have been published comparing motion preservation surgery with nonoperative therapy. 2 As nonoperative management of spinal pathology maintains the spine’s natural motion and has none of the operative risks of either fusion or disc arthroplasty, it may be the ultimate “motion-sparing” therapy for select spinal pathology.

Lumbar Spine

The major indication for lumbar disc arthroplasty is chronic back pain associated with degenerative disc disease. A number of studies have demonstrated that lumbar disc arthroplasty provides results equivalent to those of lumbar fusion. Three randomized controlled trials of fusion for chronic back pain, with mixed results, have been published in the last decade.3–5 Fritzell et al. concluded that fusion was more effective than conservative therapy for chronic low back pain, when compared with the “usual therapy” directed by the patient’s primary care physician.5 Brox et al. observed no difference between fusion and a program of cognitive therapy and exercise.4 Fairbank et al. found that fusion was only slightly more effective than a multidisciplinary rehabilitation program.4 However, in both the Fritzell and Fairbank studies, the mean improvement in the Oswestry Disability Index (ODI) score, their primary outcome measure—11.6 and 12.5, respectively—failed to reach the threshold of 15 that the FDA considers the minimally clinically important change for the ODI.1,6,7 Based on these trials, a number of authors have concluded that for nonradicular back pain, fusion is no more effective than an intensive rehabilitation program and is associated with only small to moderate benefit when compared with standard nonsurgical therapy.6–9

Only one study to date has compared lumbar disc arthroplasty directly with nonoperative management. Hellum et al.2 conducted a multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing disc arthroplasty at L4-5 or L5-S1 with a 12- to 15-day outpatient multidisciplinary rehabilitation program. The study was powered to detect a 10-point difference on the ODI at 2 years, which was their primary outcome measure. Secondary outcome measures included low back pain, quality of life (36-Item Short Form Health Survey [SF-36], EuroQuol [EQ-5D]), Hopkins symptom check list (HSCL-25), fear avoidance beliefs (FABQ), work status, patients’ satisfaction, and drug use. A total of 173 patients were enrolled, 86 with surgery and 87 with rehabilitation. Although the study did show a significant difference in ODI scores between the two groups, it was less than the 10 points the study was powered to detect. Moreover, there was no significant difference in any of the other outcome measures between the two groups.2

Cervical Spine

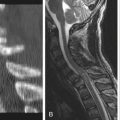

The published indications for TDA in the cervical spine are much broader than those for the lumbar spine. TDA has been shown to be equivalent to anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) for management of myelopathy and radiculopathy.10,11 Therefore, cervical TDA may be considered as an option in any case where a single-level ACDF may be indicated, including cervical radiculopathy, myelopathy, or neck pain secondary to single-disc-level pathology. Clearly, in cases of myelopathy or radiculopathy with progressive or severe neurologic deficit, surgery may be indicated for decompression of the neural elements. In those cases, TDA may be considered; however, it is still unclear whether TDA is any more beneficial than ACDF in either the short or long term.10,11 As with discogenic low back pain, the literature does not seem to support surgery over nonoperative management for axial neck pain.12 Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that some patients with radiculopathy who had been considered surgical candidates may improve with epidural steroid injections alone, obviating the need for surgery.13

Brox J.I., Sorensen R., Friis A., et al. Randomized clinical trial of lumbar instrumented fusion and cognitive intervention and exercises in patients with chronic low back pain and disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(17):1913-1921.

Chou R., Baisden J., Carragee E.J., et al. Surgery for low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1094-1109.

Fairbank J., Frost H., Wilson-MacDonald J., et al. Spine Stabilization Trial Group. Randomised controlled trial to compare surgical stabilisation of the lumbar spine with an intensive rehabilitation programme for patients with chronic low back pain: the MRC spine stabilisation trial. BMJ. 2005;330(7502):1233.

Fritzell P., Hagg O., Wessberg P., et al. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in Clinical Studies: Lumbar fusion versus nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(23):2521-2532.

Hellum C., Johnsen L.G., Storheim K., et al. Surgery with disc prosthesis versus rehabilitation in patients with low back pain and degenerative disc: two year follow-up of randomised study. BMJ. 2011;342:d2786.

Mirza S.K., Deyo R.A. Systematic review of randomized trials comparing lumbar fusion surgery to nonoperative care for treatment of chronic back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(7):816-823.

1. Rihn J.A., Berven S., Allen T., et al. Defining value in spine care. Am J Med Qual. 2009;24(6):4S-14S.

2. Hellum C., Johnsen L.G., Storheim K., et al. Surgery with disc prosthesis versus rehabilitation in patients with low back pain and degenerative disc: two year follow-up of randomised study. BMJ. 2011;342:d2786.

3. Brox J.I., Sorensen R., Friis A., et al. Randomized clinical trial of lumbar instrumented fusion and cognitive intervention and exercises in patients with chronic low back pain and disc degeneration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2003;28(17):1913-1921.

4. Fairbank J., Frost H., Wilson-MacDonald J., et al. Randomised controlled trial to compare surgical stabilisation of the lumbar spine with an intensive rehabilitation programme for patients with chronic low back pain: the MRC spine stabilisation trial. BMJ. 2005;330(7502):1233.

5. Fritzell P., Hagg O., Wessberg P., et al. 2001 Volvo Award Winner in Clinical Studies: Lumbar fusion versus nonsurgical treatment for chronic low back pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial from the Swedish Lumbar Spine Study Group. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2001;26(23):2521-2532.

6. Bogduk N., Andersson G. Is spinal surgery effective for back pain? F1000 Med Rep. 2009;1:60. ii

7. Mirza S.K., Deyo R.A. Systematic review of randomized trials comparing lumbar fusion surgery to nonoperative care for treatment of chronic back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(7):816-823.

8. Chou R., Baisden J., Carragee E.J., et al. Surgery for low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2009;34(10):1094-1109.

9. Hanley E.N., Herkowitz H.N., Kirkpatrick J.S., et al. Debating the value of spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2010;92:1293-1304.

10. Yu L., Song Y., Yang X., Lv C. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials: comparison of total disc replacement with anterior cervical decompression and fusion. Orthopedics. 2011;34(1):e651-e658.

11. Jaramillo-de la, Torre J.J., Grauer J.N., Yue J.J. Update on cervical disc arthroplasty: where are we and where are we going? Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2008;1:124-130.

12. Wieser E.S., Wang J.C. Surgery for neck pain. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(Suppl 1):51-56.

13. Lee S.H., Kim K.T., Kim D.H., et al. Clinical outcomes of cervical radiculopathy following epidural steroid injection: a prospective study with follow-up for more than 2 years. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Oct 21, 2011. [Epub ahead of print.]