Tissue Nematodes (Roundworms)

1. Describe the distinguishing morphologic characteristics and basic life cycle (vectors, hosts, and stages of infectivity) for each of the parasites listed.

2. Describe the diseases and mechanism of pathogenicity, including route of transmission for each of the species listed.

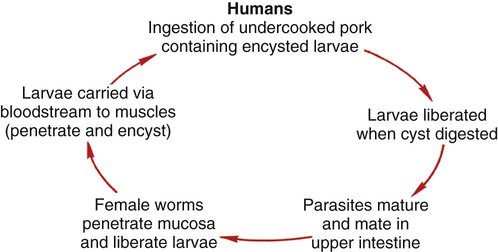

3. Describe the life cycle of Trichinella spiralis in humans and swine, including the infectious form and location of adult worms.

4. Describe trichinosis and disease progression in humans, including body sites affected, peripheral blood presentation, severity of disease, and prognosis.

5. List the various methods used to diagnose tissue nematode infections.

6. Explain the diagnosis and recommended treatment for dracunculosis.

7. Define and differentiate visceral larva migrans, ocular larva migrans, and cutaneous larva migrans.

8. Correlate patient signs and symptoms and route of transmission with the correct organisms described in this chapter.

Tissue nematodes have life cycles similar to those of intestinal nematodes, consisting of five distinct stages including adult male and female worms and four larval stages. These organisms are distributed worldwide, predominantly in the tropics and subtropics. The organisms are transmitted by three routes: biting and subsequent blood-feeding arthropods (filarial worms), as discussed in Chapter 53; ingestion of small freshwater crustaceans; and ingestion of contaminated meat. In most cases, adult worms do not multiply and develop within the human host. Clinical symptoms are dependent on the number of infecting parasites, the tissue invaded, and the host’s general health and immune response. Diagnosis is typically by the microscopic visualization of the organisms in tissue when appropriate.

Trichinella Spiralis

General Characteristics

Epidemiology

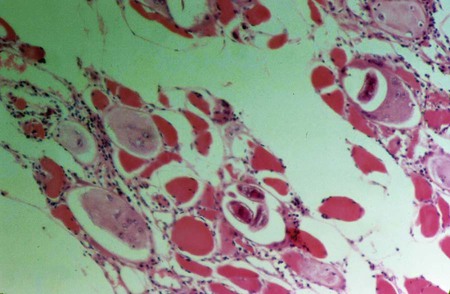

The encysted larvae are ingested. When the undercooked meat is digested in the stomach, the larvae are resistant to the gastric pH and pass to the intestine, where they invade the mucosa. In about 1.5 days, the larvae mature and mate, and the female worm begins to release motile larvae. These larvae then migrate to the lymphatic system or mesenteric venules and become distributed throughout the body. The larvae then deposit in the striated muscle tissue, where they can continue development, coil, and encyst, becoming infective. The larvae encyst in the active striated muscle including the diaphragm, larynx, tongue, jaws, neck, ribs, biceps, and gastrocnemius. The generalized life cycle is depicted in Figure 52-1. The larvae may remain viable within the cyst for several years. The larvae eventually die and the encysted capsules become calcified.

Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Disease

Trichinosis is a disease of the muscle caused by infection with the encysted larval form of Trichinella spp. (Figure 52-2). The adult stages reside in the human intestine. The disease ranges from mild to severe dependent on the number of parasites present. The intestinal stage lasts approximately 1 week and typically includes mild symptoms of nausea, abdominal discomfort, diarrhea, and/or constipation. Diarrhea may last as long as 14 weeks with no apparent muscle involvement. The migration of the larvae results in an intense inflammatory response causing periorbital edema, fever, muscle pain or tenderness, headache, and myalgia. A marked peripheral eosinophilia is often present. If the parasitic infection is low, eosinophilia may be the only diagnostic sign evident. Occasionally, splinter hemorrhages may be present below the nails.

Toxocara Canis (Visceral Larva Migrans) and Toxocara Cati (Ocular Larva Migrans)

General Characteristics

Epidemiology

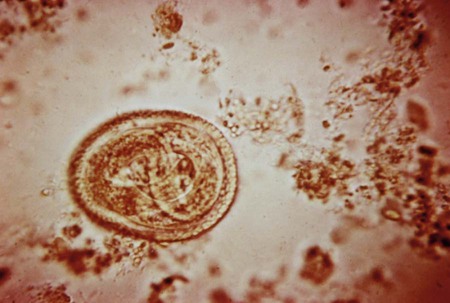

Toxocariasis is a zoonotic disease with worldwide distribution. Humans become infected with the accidental ingestion of eggs (Figure 52-3). The definitive hosts, dogs (T. canis) and cats (T. cati), pass the larvae transplacentally or lactogenically to their offspring and pass unembryonated eggs in the feces. The eggs mature in 10 to 20 days, and then become infective. Once the eggs are ingested, the larvae are released in the small intestine, penetrate the mucosa, and migrate to the liver, lungs, or other body sites. The larvae migrate up the respiratory tract and are swallowed, returning to the intestinal tract where they mature into adult worms. The adult worms are unable to mature in a human host and therefore wander throughout the body causing the migratory syndromes.

Ancylostoma Braziliense or Ancylostoma Caninum (Cutaneous Larva Migrans)

General Characteristics

Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Disease

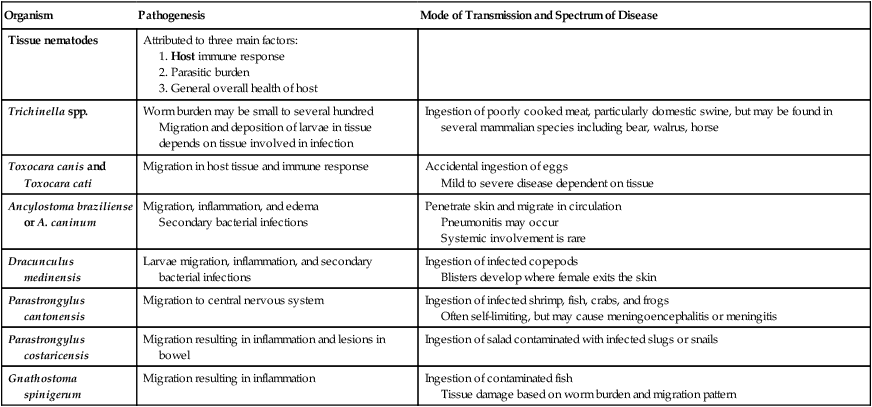

See Table 52-1 for a summarized detail of associated diseases.

TABLE 52-1

Pathogenesis and Spectrum of Associated Diseases

| Organism | Pathogenesis | Mode of Transmission and Spectrum of Disease |

| Tissue nematodes | Attributed to three main factors: |

Migration and deposition of larvae in tissue depends on tissue involved in infection

Mild to severe disease dependent on tissue

Secondary bacterial infections

Pneumonitis may occur

Systemic involvement is rare

Blisters develop where female exits the skin

Often self-limiting, but may cause meningoencephalitis or meningitis

Tissue damage based on worm burden and migration pattern