39 Tic Disorders

Phenomenology and Classification

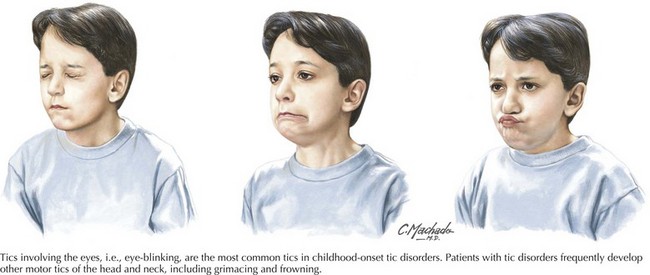

Tics are categorized as simple or complex (Box 39-1). Simple motor tics involve only one group of muscles and are characterized by quick, jerk-like movements. Usually they are abrupt in onset and brief (clonic tics) but they can also be slower and sustained (dystonic tics). Examples of simple motor tics include eye blinking, nose twitching, and shoulder shrugging. Simple phonic tics include sniffing, throat clearing, and grunting. Complex motor tics are sequenced and coordinated movements that can resemble gestures or fragments of normal behavior, e.g., kicking, jumping, and, rarely, inappropriate behavior, e.g., showing the middle finger. Complex phonic tics have a semantic basis, including words, parts of words, and obscene words (coprolalia).

Causes Of Tic Disorders

Tic disorders can be primary or secondary (Box 39-2). Primary tic disorders are discussed in the previous section and include transient tic disorder, chronic motor tic disorder, chronic vocal tic disorder, and Tourette syndrome. Less commonly, tics can be secondary to other causes, including neurodegenerative illnesses (i.e., Huntington disease, neuroacanthocytosis), infection (i.e., viral encephalitis), global developmental syndromes (i.e., static encephalopathy, autism spectrum disorders), and drugs (i.e., amphetamines, lamotrigine). Secondary causes should always be considered in adult-onset tic disorders.

Clinical Course and Natural History of Tourette Syndrome

In TS, symptoms typically begin in childhood, usually by age 7 years. Early in the course, tics frequently involve the face, head, and neck (Fig. 39-1). Vocal tics tend to start later (ages 8–15 years). The frequency and severity of tics fluctuate over time, with peak severity occurring at about 10 years of age. The anatomic locations and complexity of tics also tend to change over time. The vast majority of TS patients (85%) experience reduction in tics during and after adolescence. Tics can be exacerbated by stress, fatigue, CNS stimulants, and caffeine. Alleviation of tics can occur with focused mental and physical exercise, relaxation, and exposure to nicotine and cannabinoids.

Therapies

There are both nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic treatments for tics. It is important to recognize that the mere presence of tics does not necessarily imply a need to initiate pharmacologic treatment. One initially needs to determine the degree to which tics are interfering with functioning at school, at work, or at home and any disability associated with tics. In addition, comorbidities such as ADHD, OCD, and mood disorders need to be assessed. If tics are mild, educational and psychosocial interventions can be implemented for treatment of tics. If tics are more severe and disabling, medication treatment should be considered (Box 39-3).

The role of deep brain stimulation (DBS) in the treatment of tic disorders is being studied as a possible treatment for severe, disabling, medication-refractory tic disorders. A number of different anatomic locations are targeted, including the medial portion of the thalamus, the globus pallidus internus, the nucleus accumbens, and the anterior limb of the internal capsule. Inclusion and exclusion criteria to determine suitable TS candidates for DBS have been devised and are listed in Box 39-4. Further controlled trials of DBS in TS will need to be done to confirm the efficacy of DBS in TS and the optimal surgical target.

Ackermans L, Temel Y, Visser-Vandewalle V. Deep brain stimulation in Tourette syndrome. Neurotherapeutics. 2008;5:339-344.

Rampello L, Alvano A, Battaglia G, et al. Tic disorders: from pathophysiology to treatment. J Neurol. 2006;253:1-15.

Shprecher D, Kurlan R. The management of tics. Mov Disord. 2009;24:15-24.