167 Thyroid Disorders

• Hypothyroidism secondary to iodine deficiency is the most common endocrine disorder worldwide.

• Primary hypothyroidism results from dysfunction of thyroid tissue. Secondary hypothyroidism is a component of panhypopituitarism that results from pituitary disease.

• Severe hypothyroidism is a rare condition characterized by altered mental status, hypothermia, and primary thyroid dysfunction. Myxedema is seen in most cases; true coma is not.

• Patients with suspected severe hypothyroidism should receive empiric, low-dose intravenous levothyroxine.

• Thyroid storm, the most extreme form of thyrotoxicosis, is a rapidly fatal condition.

• Antithyroid medication should be given at least 1 hour before the administration of iodine for the treatment of thyroid storm.

• Emergency department testing for thyroid disease includes serum thyrotropin, or thyroid-stimulating hormone, and free thyroxine measurements.

Epidemiology

Abnormal thyroid function is by far the most common endocrine disorder worldwide and is second only to diabetes mellitus in the United States. Thyrotoxicosis is a rare condition that is 10 times more prevalent in women than in men (2% versus 0.2%).1 It is uncommon before the age of 15 years.2 Although most manifestations of thyrotoxicosis do not represent a true emergency, the extreme case of so-called thyroid storm does. Early detection and treatment of this condition may prevent progression to shock and death.

Hypothyroidism

Clinical Presentation

Hypothyroidism is a deficiency of thyroid hormones that results in decreased metabolic activity. It mimics many conditions commonly encountered in the emergency department (ED) and is accompanied by a myriad of indolent symptoms (Boxes 167.1 and 167.2).

In a recent study of the incidence of newly diagnosed primary overt hypothyroidism in adults seen in a Taiwanese ED, the most common symptoms were fatigue (50%), dyspnea (45%), chest tightness (20%), constipation (14%), and cold intolerance (9%). The majority of these patients were seen during winter months. In only 21% was hypothyroidism diagnosed by the emergency physician.3

Severe Hypothyroidism (Myxedema Coma)

Patients with severe hypothyroidism may have mild to moderate hypothermia, depression, lack of energy, and altered mental status. Myxedema coma is a misnomer often used for severe hypothyroidism; not all patients with severe hypothyroidism are truly comatose, whereas most (but not all) patients with hypothyroid coma have myxedema. Myxedema coma best describes a patient in extremis secondary to a severe hypothyroid state (Box 167.3).

Treatment

Severe Hypothyroidism (Myxedema Coma)

Management of severe hypothyroidism consists of standard ED resuscitation measures, including consideration and empiric treatment of potential sepsis. The only treatment step specific for severe hypothyroidism is intravenous (IV) administration of levothyroxine. Empiric administration of low-dose levothyroxine is appropriate in patients in whom a serum TSH level cannot be obtained in timely fashion. ED treatment of myxedema coma is summarized in Box 167.4.

Box 167.4 Emergency Department Treatment of Myxedema Coma

Provide airway support and supplemental oxygen as needed. Check bedsid e glucose.

Obtain serum laboratory tests: complete blood count, comprehensive metabolic panel, thyroid-stimulating hormone, free thyroxin, cortisol.

Evaluate for other causes of altered mental status; for example, infection, medication or recreational drug effect, intracranial pathology.

Consider broad-spectrum antibiotics.

Support temperature with passive rewarming.

Administer 0.3 to 0.5 mg of levothyroxine intravenously; decrease to 0.1 mg in patients with suspected heart disease.

Thyrotoxicosis

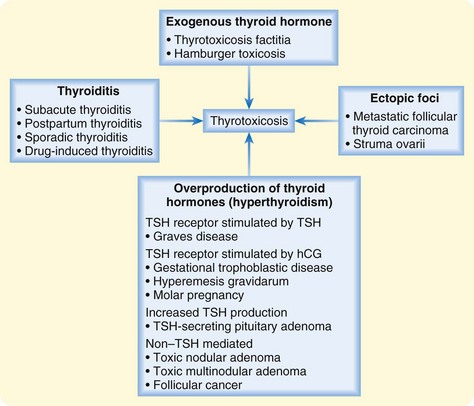

Thyrotoxicosis is caused by at least one of four potential mechanisms:

1. Overproduction of thyroid hormones by the thyroid gland

2. Unregulated release of thyroid hormones secondary to destruction of thyroid cells (thyroiditis)

3. Ingestion of thyroid hormones

4. Production of thyroid hormones from ectopic foci (Fig. 167.1)

Fig. 167.1 Causes of thyrotoxicosis.

hCG, Human chorionic gonadotropin; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

Causes

Graves Disease

Graves disease, the most common cause of hyperthyroidism, accounts for approximately 60% to 80% of cases of hyperthyroidism in the United States. It is the most common autoimmune disorder in North America. In this disease, thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulins (an IgG antibody) bind to and activate thyrotropin receptors on thyroid cells, thereby mimicking the action of TSH. Continued binding of the antibody to the TSH receptor leads to excessive production of T3 and thyroid enlargement.4

Thyroiditis

Autoimmune destruction of thyroid cells is seen in patients with Hashimoto thyroiditis, painless sporadic thyroiditis, and painless postpartum thyroiditis. Hashimoto thyroiditis is characterized by high levels of serum antithyroid antibodies. This condition is the most common cause of hypothyroidism in the United States.5 Painless postpartum thyroiditis occurs in up to 10% of American women. Its onset is usually 1 to 6 months after delivery. Approximately 80% of women recover normal thyroid function within a year. The chance of recurrence with subsequent pregnancies is 70%.6

Painful subacute (de Quervain) thyroiditis is the most common cause of thyroid pain. It is a self-limited disorder that is frequently preceded by an upper respiratory infection. Suppurative thyroiditis is a very rare condition that is caused by bacterial, fungal, or mycobacterial infection of the thyroid gland. It may be seen in severely immunocompromised patients. Additionally, amiodarone and lithium can cause drug-induced thyroiditis.7

Non–Thyroid-Stimulating Hormone–Mediated Hyperthyroidism

Hyperthyroidism is sometimes caused by a benign, monoclonal, autonomously secreting thyroid nodule known as toxic adenoma (Plummer disease). When more than one nodule is present, it is referred to as toxic multinodular goiter. This condition is the second most common cause of thyrotoxicosis and accounts for 5% to 15% of all cases of thyrotoxicosis. In the United States, toxic multinodular goiter is primarily seen in persons older than 50 years and accounts for more than 40% of all cases of thyrotoxicosis in this age group.8 Similarly, thyroid follicular cell cancer can likewise lead to excessive production of thyroid hormones.

Clinical Presentation

Thyrotoxicosis can be asymptomatic (subclinical hyperthyroidism) or feature mild, moderate, or severe symptoms that result from a surge in catecholamines. Patients with classic thyrotoxicosis may appear nervous, irritable, and tremulous. They may complain of unintentional weight loss, palpitations, exertional dyspnea, heat intolerance, thinning of their hair, irregular menses, increased frequency of bowel movements, and sleep disturbance. On physical examination, patients may have a palpable goiter, warm moist skin, sinus tachycardia out of proportion to fever, or atrial fibrillation on electrocardiography.9

Patients with Graves disease may have the following physical findings: goiter, periorbital ecchymosis, chemosis, proptosis, lid retraction, and lower extremity edema.4,10 Patients with painful subacute thyroiditis may have fever, malaise, myalgias, fatigue, and neck pain in addition to the symptoms of thyrotoxicosis mentioned previously.

Variations

Pregnancy

Women of childbearing age represent the peak incidence of thyroid disease; however, this presents a clinical dilemma because thyrotoxicosis can mimic the normal physiologic changes of pregnancy. In addition to the symptoms mentioned previously, pregnant patients may have inappropriate weight gain for gestational age, fetal intrauterine growth retardation, and tachycardia that does not slow with a Valsalva maneuver or with fluids.11

Elderly Patients

Patients older than 60 years may not exhibit signs of increased catecholamine levels12; instead, older adults may have a small goiter, slow atrial fibrillation, weight loss, and severe depression. This manifestation is termed apathetic thyrotoxicosis.13 Other findings in the elderly include atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure.

Thyroid Storm

Thyroid storm represents the extreme manifestation of thyrotoxicosis. Approximately 1% to 2% of patients with thyrotoxicosis progress to thyroid storm. Common precipitants of this condition are listed in Box 167.5. Patients in thyroid storm may exhibit fever, signs of congestive heart failure, agitation, psychosis, and coma. It is a rapidly fatal condition with a mortality rate of 20% to 30% in hospitalized patients.14

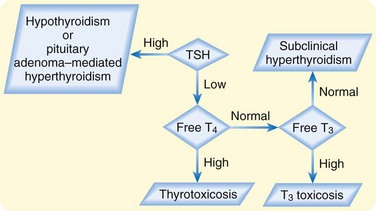

Diagnosis

The most useful ED tests for diagnosing thyrotoxicosis are TSH and FT4 measurements. The algorithm in Figure 167.2 provides an interpretation of variable TSH, FT4, and free triiodothyronine (FT3) levels. Box 167.6 lists conditions that should be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Fig. 167.2 Interpretation of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), free T4 (FT4), and free T3 (FT3) levels.

Patients with painful subacute thyroiditis will have an elevated serum erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein levels. Box 167.7 lists the tests that should be obtained in the ED for patients in thyroid storm. If thyrotoxicosis is suspected, an endocrinologist may schedule further testing to confirm the diagnosis and determine the cause. Such tests may include measurement of total T3, thyroid autoantibodies, and radioactive iodine uptake; ultrasonography; and fine-needle biopsy.

Treatment

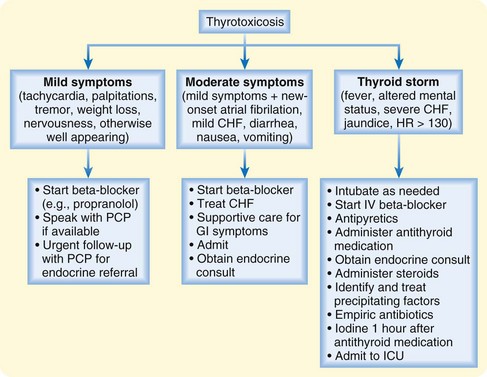

A beta-blocker should be started in patients with mild symptoms to provide symptomatic relief from tremors, palpitations, tachycardia, sweating, and anxiety (Fig. 167.3). It is important to withhold other treatment until the cause of the thyrotoxicosis is confirmed.15 Treatment options include antithyroid medications, radioactive iodine ablation, and surgery. The risks and benefits of these treatments must be weighed by the patient and the endocrinologist.

Brent GA. Clinical practice. Graves’ disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2594–2605.

Chen YJ, Hou SK, How CK, et al. Diagnosis of unrecognized primary overt hypothyroidism in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:866–870.

Cooper DS. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet. 2003;362:459–468.

Pearce EN, Farwell AP, Braverman LE. Thyroiditis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2646–2655.

Ringel MD. Management of hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 2001;17:59–74.

1 Tunbridge WM, Evered DC, Hall R, et al. The spectrum of thyroid disease in a community: the Whickham Survey. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1977;7:481–493.

2 Mckeown NJ, Tews MC, Gossain VV, et al. Hyperthyroidism. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2005;23:669–685.

3 Chen YJ, Hou SK, How CK, et al. Diagnosis of unrecognized primary overt hypothyroidism in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:866–870.

4 Brent GA. Clinical practice. Graves’ disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2594–2605.

5 Pearce EN, Farwell AP, Braverman LE. Thyroiditis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2646–2655.

6 Lazarus JH. The continuing saga of postpartum thyroiditis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:614–616.

7 Ma RC, Kong AP, Chan N, et al. Drug-induced endocrine and metabolic disorders. Drug Saf. 2007;30:215–245.

8 Porterfield JR, Thompson GB, Farley DR, et al. Evidence-based management of toxic multinodular goiter (Plummer’s disease). World J Surg. 2008;32:1278–1284.

9 Osman F, Franklyn JA, Holder RL, et al. Cardiovascular manifestations of hyperthyroidism before and after antithyroid therapy: a matched case-control study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49:71–81.

10 Weetman AP. Graves’ disease. N Engl J. Med 2000;343:1236–1248.

11 Casaletto JJ. Is salt, vitamin or endocrinopathy causing this encephalopathy? A review of endocrine and metabolic causes of altered level of consciousness. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2010;28:633–662.

12 Boelaert K, Torlinska B, Holder RL, et al. Older subjects with hyperthyroidism present with a paucity of symptoms and signs: a large cross sectional study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2715–2726.

13 Cooper DS, Greenspan FS, Ladenson PW. The thyroid gland. In: Gardner DG, Shoback D. Greenspan’s basic and clinical endocrinology. 8th ed. San Francisco: McGraw-Hill; 2007:215–294.

14 Nayak B, Burman K. Thyrotoxicosis and thyroid storm. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2006;35:663–686.

15 Cooper DS. Antithyroid drugs. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:905–917.

16 Cooper DS. Hyperthyroidism. Lancet. 2003;362:459–468.

17 Ringel MD. Management of hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 2001;17:59–74.