Is There a Role for Bowel Preparation and Oral or Parenteral Antibiotics In Infection Control in Contemporary Colon Surgery?

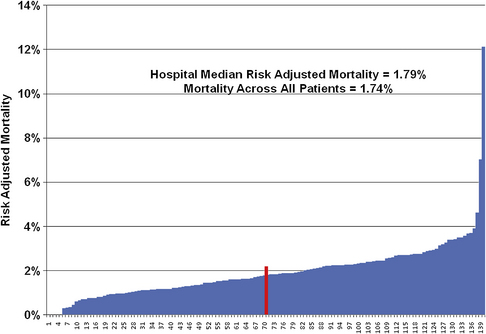

Over the past 90 years, colorectal resection has been associated with a progressive increase in safety for what is still a major and frequently performed operation. It has often been stated that the wide use of antibiotics after World War II was associated with increasing survival after colon surgery [1]; as a matter of fact, the broad application and use of blood banks in the late 1930s [2] and the improved care overall associated with the proliferation of intensive care units in the 1990s correlate better with those improvements. Although there are still outliers in institutional mortality rates in colon surgery, the mortality rate for a large number of voluntarily reporting university teaching and affiliated hospitals is just under 2% for elective operations. Interestingly, even after anastomotic leak, rescue by an early diagnosis and appropriate systemic management, often including diversion, is so much the rule that death rates are still low (Fig. 1) [3].

One major predisposing factor for untoward results in patients who must undergo colon resection is having the operation after a hospitalization of several days. Obviously, that environment sets the stage for a substantial increase in infection rates, often with antibiotic-resistant, hospital-acquired bacteria [4]. Another major trend recently has included omission of bowel preparation to decrease morbidity, especially dehydration in the elderly.

There has been a dramatic shift toward both laparoscopic and robotic colon resection and the use of a variety of stapling devices for anastomoses [5–8]. There has also been an improved standardization of the operation for rectal cancer, including performance of meso-rectal excision with better oncologic outcomes [9]. At this point in time, practice patterns in North America show 90% of segmental colon resections being performed by general surgeons and approximately 75% of all rectal cancer excisions performed by colorectal surgeons. This finding may well represent a worthy professional sharing of procedures of the type discussed herein. Another significant advance over this decade has been the broad, even worldwide implementation of fast-track pathways for elective surgery, to both decrease hospital length of stay and reduce nonoperative complications, as has been studied and described repeatedly by Kehlet [10].

For the purposes of this review, it is presumed that the vast majority of colon resections, especially the elective ones, are performed for colon cancer or diverticulitis. In this setting, oral antibiotics and bowel preparation with laxatives are less widely used now than they were 10 years ago. Emergency surgery of the colon, such as for hemorrhage or obstruction or acute diverticulitis, produces entirely different outcomes with in-hospital death rates ranging from 16% to 25% in many recent reports [11]. Furthermore, interest in 1- and 2-year survival rates has disclosed more late deaths than commonly known, often but not exclusively caused by progression or recurrence of cancer and intercurrent disease, such as cardiovascular disorders.

Parenteral antibiotic administration

Surgical site or operative wound infection rates for elective colon resection were as high as 80% in the 1930s [12], and progressively improved to approximately 40% by the end of the 1960s. Effective preoperative systemic antibiotics as defined by Polk and Lopez-Mayor [13] further reduced surgical site infection (SSI) rates and no further placebo-controlled trials are necessary to prove that generally accepted point [14]. SSI does have variably reported rates. However, literally hundreds of reports on colorectal or other gastrointestinal operations support this view, of which a few deserve further reference [15–17]. During the last 2 decades, there have been at least 3 rigorously evaluated patient studies following elective colorectal resection that have shown SSI rates higher than expected when appropriate systemic antibiotics were given and patients were followed for 30 days following operation [12,17,18]. Many recent quality and safety studies [19] focus on 3 factors: (1) choice of an antibiotic with emphasis on safety, an appropriate spectrum, and one that remains in the incision for the duration of the operation; (2) administration of the first dose, ideally 30 minutes before incision; and (3) prompt discontinuation of the systemic antibiotic is important, even a single dose, to avoid antibiotic-related serious morbidity, such as Clostridium difficile colitis as notably reported with ertapenem [20].

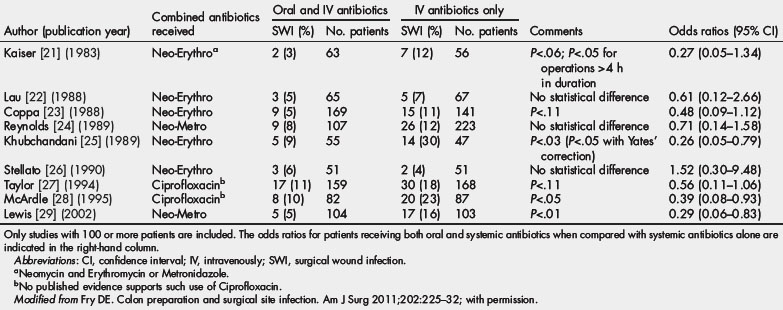

The authors think that additional methods may be needed to supplement systemic antibiotics, especially when errors of omission or commission, as previously noted, occur (Table 1) [21–29]. Accurate timing of the first dose related to time of incision and prompt discontinuation is essential [30].

Mechanical bowel preparation

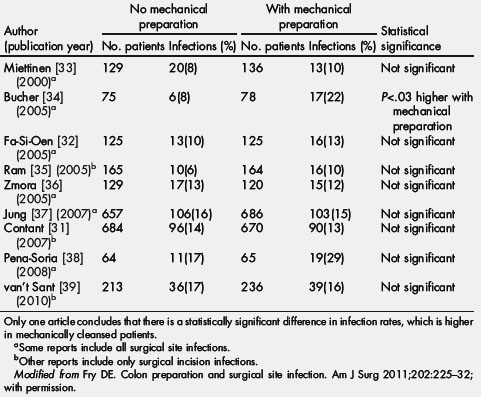

Preoperative preparation of the colon has been a special method of prevention of SSI. Human stool may have as many as 1012 bacteria per gram and purging fecal material before colonic surgery has always seemed intuitively correct [31,32]. Actually, mechanical cleansing alone does not reduce the density of bacteria in the mucosal fluid and it has never been shown to reduce SSI by itself. This conclusion was recognized 70 years ago and has been revalidated by a host of clinical trials (Table 2) [31–39] and the obligatory meta-analysis over the last 10 years [40]. The recently identified failures of mechanical preparation have led to some surgeons abandoning preparation altogether. Understanding the failure of mechanical preparation alone led clinicians in the pre-World War II and post-World War II era to pursue antimicrobial methods to reduce the bacterial concentration of colonic contents [1,41–43].

Table 2 A summary of the prospective randomized trials of no mechanical bowel preparation versus patients receiving mechanical bowel preparation in elective colon surgery (2000 to 2010)

Which mechanical bowel preparation is best? There have been many different preparations used and polyethylene glycol is the most popular. One clinical trial suggests that sodium phosphate may give the best result [44], although it has been associated with hyperphosphatemia [45]. Recent experiments implicate enhanced microbial virulence when intracolonic phosphate concentrations are low, providing a scientific argument for phosphate in the colonic preparation [46]. Different mechanical preparations need to be evaluated to define best cleansing results but also best patient acceptance. One meta-analysis tries to assess the overall value of oral antibiotics [29].

Oral antibiotic use

Despite early efforts with sulfa preparations [47] and with kanamycin [48], a successful randomized clinical trial was not done until that reported by Washington and colleagues using oral neomycin and tetracycline compared with mechanical preparation alone [49]. Clarke and colleagues validated the use of neomycin and erythromycin base compared with mechanical preparation and a placebo [50]. This latter combination became most popular in the United States, and by the end of the 1990s the oral antibiotic bowel preparation combined with preoperative systemic antibiotics was the most common strategy employed in elective colon surgery [23–25]. Lewis has further validated the merits of the oral antibiotic bowel preparation by conducting a randomized clinical trial of oral neomycin/metronidazole plus systemic antibiotics versus systemic antibiotics alone [51], supplemented by a detailed meta-analysis of clinical trials dating back to 1998 demonstrating significance (P<.0001) in favor of the combination of the oral antibiotic bowel preparation with systemic antibiotic [26–28,34,51].

Despite this evidence, the oral antibiotic bowel preparation is currently not being generally used and never has been well accepted outside of the United States and Canada. Prehospitalization bowel preparation has often been poor in terms of the quality of preparation. Patients complain about the discomfort of the mechanical preparation, and the abdominal cramping associated with erythromycin result in poor compliance and resultant poor preparation. Surgeon disillusionment with poor quality of preparation has led to decreasing use of the oral and mechanical bowel preparation, and there is some evidence that the polyethylene glycol mechanical preparation may increase infection rates [4,44].

Even with the application of effective oral antibiotic bowel preparation and the appropriate protocol for systemic antibiotics, the SSI rates remain approximately 5%. The development of the oral antibiotic bowel preparation has been inconsistent over time, with many unanswered questions. It also remains unclear which oral antibiotic regimen is best. Neomycin has been questioned in terms of its effectiveness [51]. Erythromycin is associated with gastrointestinal motility problems. Metronidazole is significantly absorbed and may not yield optimum intraluminal drug concentrations. Instead of additional trials challenging the use of mechanical preparation and reaffirming the literature of 70 years ago, new prospective trials evaluating different oral antibiotics may be worthwhile.

Finally, it is appreciated by all that combined oral antibiotic bowel preparation and concomitant systemic antibiotics disrupt the normal colonic ecosystem. A retrospective study implicates oral antibiotics with the postoperative development of C difficile enterocolitis [4], which is a serious and occasionally fatal complication. It is certain that the inappropriate continuation of systemic antibiotics after completion of the colorectal resection increases antibiotic-associated enterocolitis events. Can probiotics administered after completion of the operation be of advantage in the restoration of a normal colonic microflora? This question also deserves study.

Perhaps it is also valuable to offer an example of a common clinical scenario: an elderly patient needing an elective colon resection but whose case is complicated by moderate renal impairment and a chronic cardiac arrhythmia, both of which predispose to complications and a higher death rate. Many surgeons use a longer, gentler mechanical preparation and determine a variety of laboratory studies 24 hours preoperatively, which may lead to supplemental preoperative intravenous fluids. Better careful early than regretful later. All of these considerations have led to the gradual omission of mechanical bowel preparation. Many studies have suggested that its use is associated with increased electrolyte disturbances, increased morbidity, and increased overall adverse outcome. Guenaga, Matos, and Wille-Jorgensen via the Cochrane Collaboration concluded that there is no statistically significant evidence that patients benefit from mechanical bowel preparation [53].

Nonetheless, many surgeons are still reluctant to abandon bowel preparation, and provided they have acceptable SSI rates and low postoperative morbidity, this can be justified. One of the main factors pushing toward omission of bowel preparation is, undoubtedly, poor patient compliance and the poor palatability of currently available preparations (see Table 2).

Besides oral and systemic antibiotics, is there a role for local antibiotic delivery to the surgical site? Instilling antibiotic solution into the wound bed via small drains for 72 hours postoperatively can be a useful method of reducing wound infection rates, the preferred method for the first author for 2 decades with generally good results in cases with contamination or other high-risk wounds [54]. Although infrequently studied and reported, many surgeons apply topical antibiotics to the incision after fascial closure, although the most efficacious and least harmful drug remains to be determined [55]. To date, no randomized clinical trials have demonstrated that topical antibiotics have improved outcomes over appropriately administered preoperative systemic antibiotics in the prevention of SSI after colon surgery.