19 The Treatment of Pain Through Chinese Scalp Acupuncture

Around 1950, various famous Chinese physicians introduced Western neurophysiology into acupuncture fields and explored the relationship between the brain and human body. Although there were several hypotheses, it took acupuncture practitioners roughly 20 years before they accepted a central theory that incorporated brain functions into the Chinese meridian theories. Dr. Jiao Shunfa, a neurosurgeon in Shanxi province in China, is the official recognized founder of Chinese scalp acupuncture.1 Starting in 1972, he systematically undertook the scientific exploration and charting of scalp correspondences for the first time in more than 2500 years of acupuncture history. Dr. Jiao combined a modern understanding of neuroanatomy and neurophysiology with traditional techniques of Chinese acupuncture to develop a radical new tool for treating the central nervous system. At the time, scalp acupuncture was primarily used to treat paralysis and aphasia due to stroke. Dr. Jiao’s discovery was investigated, acknowledged, and formally recognized by the acupuncture profession in a national unified acupuncture textbook, Acupuncture and Moxibustion in 1977.

In 1987, scalp acupuncture began to gain international recognition at the first International Acupuncture and Moxibustion Conference held in Beijing. In 1989, Dr. Jason Jishun Hao brought scalp acupuncture to the United States. Since then, Dr. Hao has trained hundreds of acupuncture practitioners and treated thousands of patients with disorders of the central nervous system in the United States. After its introduction in the United States, the techniques and applications of scalp acupuncture have been expanded and developed through further research and experience. Studies and research on scalp acupuncture continue to show positive results in treating the disorders of the central nervous system.2

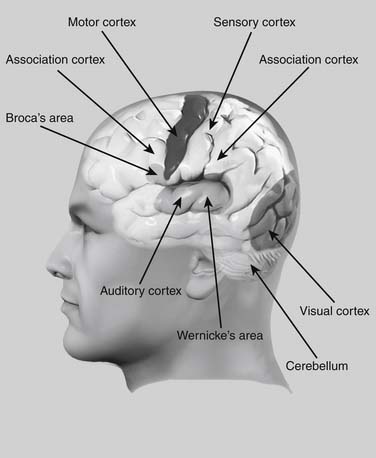

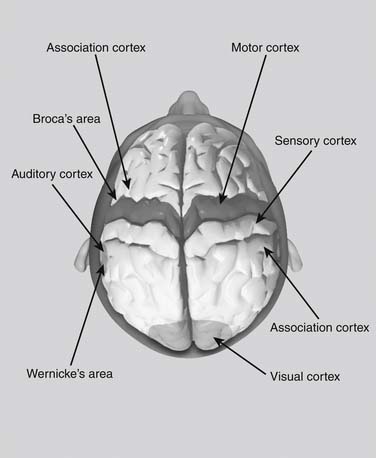

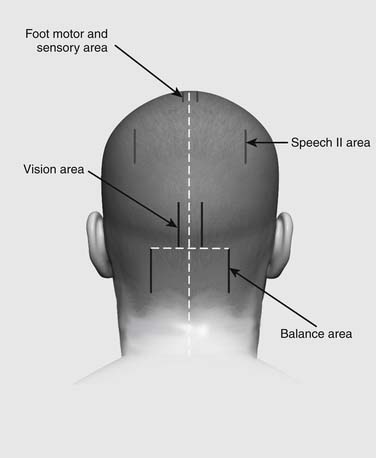

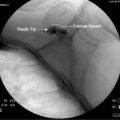

Scalp acupuncture is based on a reflex somatotopic system organized on the surface of the scalp. Scalp acupuncture consists of needling areas versus points on the skull according to the brain’s neuroanatomy and neurophysiology. Unlike acupuncture, where one needle is inserted into a single point, in scalp acupuncture needles are subcutaneously inserted into whole sections of various zones. These sections are the specific zones through which the functions of the central nervous system, endocrine system, and meridians are transported to and from the surface of the scalp. From a Western perspective, these areas correspond to the cortical areas of the cerebrum and cerebellum, which are responsible for central nervous system functions such as motor function, speech, and balance (Figs. 19-1 and 19-2).

In a recent study by the author, scalp acupuncture was used to treat seven patients with phantom limb pain at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C.3 After only one treatment per patient, three of the seven patients instantly felt pain relief and showed significant improvement, whereas three patients showed some improvement, and only one patient showed no improvement (see later). Because of the limited numbers of patients, this needs to be replicated on a larger scale. It nevertheless shows the potential efficacy of scalp acupuncture in treating phantom pain.

Scalp acupuncture can provide solutions in situations where Western medicine solutions are limited or entail too much risk. This chapter will show the scope of scalp acupuncture in treating many kinds of diseases. This research is derived from many years of clinical experience and can be used as the foundation for future clinical practice and research.

Location and Indication

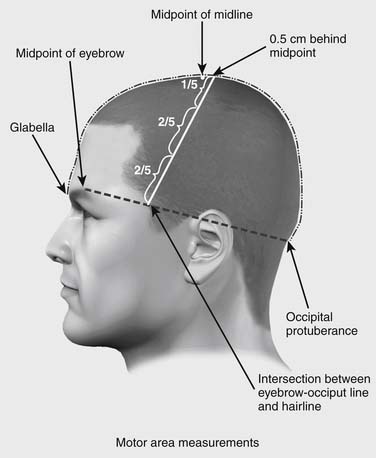

Precise location of Chinese scalp acupuncture areas requires identification of two imaginary lines on the head. The anterior-posterior line runs along the centerline of the head. The midpoint of the skull is located at the midpoint between the occipital protuberance and the glabella, midway between the eyebrows. The second line, the horizontal line, runs from the highest point of the eyebrow to the occipital protuberance. Where this line intersects the anterior hairline defines the lower point of the motor area (Fig. 19-3). In patients without a definite hairline, an alternative method for locating this point is to draw a vertical line up from acupuncture point ST-7 until it intersects the line from the brow to the occipital.

Motor Area Location

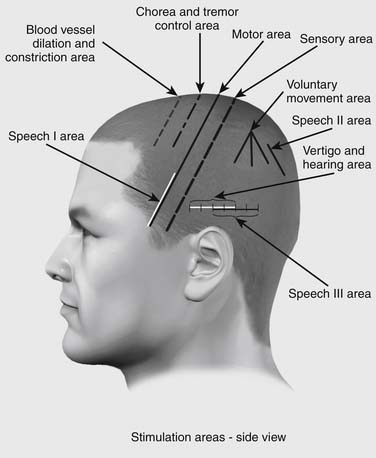

The motor area is located on the projective area of the scalp corresponding to the precentral gyrus of the frontal lobe. The motor area is located in a strip beginning at the midline at a point 0.5 cm posterior to the previously located midpoint of the head, along the anterior-posterior line.4 The motor area runs from this point obliquely down to the point where the eyebrow-occipital line intersects the anterior hairline (Fig. 19-4). The line of the motor area determines the angle and location of several other areas, such as the sensory area and chorea and tremor area.

The motor area is divided into three regions according to the homunculus projection.5 In order to correctly locate those three regions, the whole motor area is first equally divided into fifths. Then three regions are measured as Upper one-fifth region, Middle two-fifths region, and Lower two-fifths region. The Upper one-fifth region is used to treat contralateral movement dysfunction of the lower extremity, trunk, spinal cord, and neck. The Middle two-fifths region is used to treat contralateral movement dysfunction of the upper extremity. The Lower two-fifths region is used to treat bilateral movement dysfunction of the face and head. These areas are used to affect the contralateral side of the body. The direction of needling is usually from the upper part of the area downward, penetrating to the entire area.

Motor Area Indications

Indications to apply needles in the motor area are: paralysis or weakness in the face, trunk, or limbs caused by stroke; multiple sclerosis; traumatic paraplegia; acute myelitis; progressive myotrophy; neuritis; poliomyelitis; post-polio syndrome; periodic paralysis; hysterical paralysis; Bell’s palsy; spinal cord injury; traumatic brain injury; and brain surgery.

Sensory Area Location

The sensory area is located on the projective area of the scalp corresponding to the post-central gyrus of the frontal lobe. The sensory area is one of the most commonly used in Chinese scalp acupuncture. It is located parallel to the motor area, 1.5 cm posterior to the motor area (see Fig. 19-4).

Additional Areas of the Cortex

Tremor and Chorea Area

The Chorea and Tremor Area is located parallel to the motor area, 1.5 cm anterior to the motor area (see Fig. 19-4). It runs 4 cm and starts 1 cm anterior to the Midpoint at its upper point. This area is always needled bilaterally and is used for any involuntary motor activity. This is the primary area for the treatment for Parkinson’s disease, tremor, shaking of the head, body, or extremities, and chorea. This area is also very effective for treating patients with muscular tension and tightness in any part of the body. The direction of needling is usually from the upper part of the area downward, penetrating to the entire area.

Vascular Dilation and Constriction Area

This area is also parallel to the motor area, 1.5 cm anterior to the chorea and tremor area, or 3 cm anterior to the motor area (see Fig. 19-4). This area is also always needled bilaterally and can be used for essential hypertension, cortical edema, and other autonomic vascular dysfunctions. The direction of needling is usually from the upper part of the area downward, penetrating the entire area.

Vertigo and Hearing Area

This area is located over temporal lobe in the lateral side of the head. It is on the horizontal line and totals 4 cm.6 It starts 1.5 cm superior to the apex of the auricle of the ear at its middle point, and extends 2 cm anterior and 2 cm posterior to the middle point (see Fig. 19-4). This area is also needled bilaterally and can be needled in either direction. This is a very useful area for treating vertigo, dizziness, Meniere disease, tinnitus, hearing loss, and hearing hallucination.

Speech I Area

There are three speech areas. Speech I area is located in the posterior third of the gyrus frontalis inferior over the frontal lobe, and controls groups of muscles for speech and phonation. Speech I area corresponds to Broca’s speech area of the frontal lobe, which controls the muscles of the tongue and mouth that form speech. Speech I area overlaps the lower 2/5 40% of the motor area (see Fig. 19-4). The major indication for Speech I is in the presence of motor aphasia after stroke or brain injury, where the muscles of speech and vocalization have been paralyzed. This area is needled bilaterally for motor aphasia. The direction of needling is usually from the upper part of the area downward, penetrating the entire area.

Speech II Area

This area lies over the reading and comprehension part of the parietal lobe, and is located by finding the parietal tubercle. From the parietal tubercle, run a line parallel to the anterior-posterior line 2 cm posteriorly. Using this as the starting point, the Speech II area runs 3 cm in length, parallel to the anterior-posterior line (see Fig. 19-4). This area is used bilaterally for nominal aphasia—the inability to name objects. In this disorder, the patient can describe an object, but cannot produce the noun. The direction of needling is usually from the upper part of the area downward.

Speech III Area

This overlies Wernicke’s area of the temporal lobe, and overlaps the posterior half of the vertigo and hearing area. It lies on the same horizontal line 1.5 cm superior to the apex of the auricle but begins at the midpoint of the vertigo and hearing area directly above the auricle and runs 4 cm posteriorly (see Fig. 19-4). It is used bilaterally for treatment of expressive aphasia, where the patient can articulate words, but the words don’t make sense. The direction of needling can go either from the left part to the right or from right to left side, penetrating the entire area.

Praxis Area

This is an area used uncommonly. Starting from the parietal tubercle, the praxis area joins three lines, one running straight downward, and the other two at a 40-degree angle anterior and posterior to the vertical line (see Fig. 19-4). This area is used for apraxia—the inability to execute certain fine motor activities such as buttoning a shirt.

Vision Area

The vision area is located over the occipital lobe on the posterior aspect of the head. It starts on a horizontal line at the level of the occipital protuberance. The vision area starts at a point 1 cm lateral to the occipital protuberance and runs upward for 4 cm, parallel to the anterior-posterior line (Fig. 19-5). The vision area is often needled bilaterally. Unlike other scalp areas in Chinese acupuncture, the vision area must be needled from the top down. Needling from below upward incorrectly has the risk for causing injury to the medulla. Indications for needling are vision loss due to stroke or brain injury, visual field loss, visual hallucination, and nystagmus.

Balance Area

The balance area is located over the cerebellum. It starts on a horizontal line at the level of the occipital protuberance. The balance area starts from a point 3.5 cm lateral to the occipital protuberance and runs 4 cm inferiorly (see Fig. 19-5).

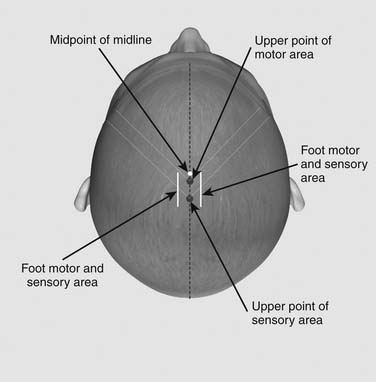

Foot Motor and Sensory Area (FMSA)

The foot motor and sensory area is the most commonly used one in Chinese scalp acupuncture. It has broad-ranging effects on both motor and sensory functions. The FMSA is located parallel to the anterior-posterior line, 1 cm lateral to the midline beginning at the level of the midpoint of anterior-posterior line and running 4 cm posteriorly (Fig. 19-6). The foot motor and sensory area gets its name from including both the motor area and the sensory area in the region of the foot on the homunculus.

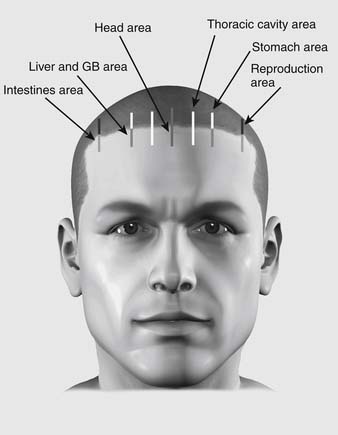

Head Area

The head area is located on the midline at the forehead, running from the hairline 2 cm superiorly and inferiorly (Fig. 19-7). This area is used for treating mental and emotional disorders, such as insomnia, poor memory, poor concentration, anxiety, and depression.

Thoracic Cavity Area

This is located half the distance between the stomach area and the midline, running from the hairline 2 cm superiorly and inferiorly (See Fig. 19-7). This area is used for treating asthma or tachycardia.

Stomach Area

This is located on the midpupillary line from the hairline 2 cm superiorly (see Fig. 19-7). This area is used for treating stomach pain and discomfort in the upper epigastric region.

Liver and Gallbladder Area

The liver and gallbladder line descends onto the forehead for 2 cm along the midpupillary line (see Fig. 19-7). This area is used for treating costal pain and rib pain due to hepatitis, gallstone, and shingles.

Needle Techniques

Clinical Applications and Case Studies

Phantom Limb Pain, Residual Limb Pain, and Complex Regional Pain

Phantom limb pain, residual limb pain, and complex regional pain are common symptoms for patients with limb injuries and/or amputations. Several studies have shown that approximately 70% to 80% of patients develop pain within the first few days after amputation. Phantom limb pain is the term for abnormal sensation perceived from a previously amputated limb.7 Patients may feel a variety of sensations emanating from the absent limb. The limb may feel completely intact despite its absence. Patients often describe their pain as burning, squeezing, cramping, prickling, shooting, or stabbing sensations. Residual limb pain is believed to come from injured nerves at the amputation site. Residual limb pain is often associated with phantom limb sensation and pain, and may be related in etiology. Complex regional pain is a “chronic pain syndrome with severe pain, changes in the nails, bones, skin, and an increased sensitivity to touch in the affected limb.” The former term for this was reflex sympathetic dystrophy.

Several theories have been proposed regarding the cause of phantom limb pain. An understanding of the mechanisms underlying phantom pain is likely to lead to new and logical types of treatments. Some studies have indicated that phantom pain might originate in the brain. Other areas of the brain fill in when the area of the brain that controlled the limb no longer has a function after amputation. There is a reorganization of the primary sensory cortex, subcortex, and thalamus after amputation. The reorganization of the sensory cortex is currently considered to be responsible for phantom limb pain.

Case Report 3—Complex Regional Pain

As soon as the needles were inserted in his scalp, the patient experienced a “water bubble-like sensation.” First the sensation moved from his right hip to his leg, then to his foot and toes. Five to eight minutes later, his leg and foot pain started to diminish and he was able to make contact with his leg and toes with little discomfort. The patient was so excited to feel the results that he continued to touch his leg and toes to verify that they really were better. He was asked to try to put a sock on his right foot and he did so without showing pain or discomfort. The patient then proceeded to take a short nap. At the follow-up visit the next day, the patient was lying on the bed with both socks on. He had very little pain and was much less sensitive than before. He was able to walk with almost no pain after four needles were placed in his scalp. Each step he took brought on applause from observers.8

Stroke

Stroke survivors usually have some degree of sequelae of symptoms depending primarily on the location in the brain involved and the amount of brain tissue damaged. Disability affects about 75% of stroke survivors, and it can affect patients physically, mentally, emotionally, or a combination of all three elements. The symptoms of stroke depend on the type of stroke and the area of the brain affected. They include paralysis, weakness or abnormal sensations in limbs or face, complex regional pain, aphasia, apraxia, altered vision, problems with hearing, taste, or smell, vertigo, disequilibrium, altered coordination, difficulty swallowing, and mental and emotional changes.

Case Report 4—Stroke

Maria had a positive response to her first scalp acupuncture treatment. After the needles were inserted in her scalp, the spasms, stiffness, and tightness in her left arm and leg showed immediate improvement. Her left limbs became looser, and her daughter was able to move Maria’s leg and arm up and down with little resistance. Maria’s eyes were full of tears as she answered questions with a clear and strong voice. She said, “Thank you so much doctor. I am so glad that I can now speak very clearly again.” Several minutes later, Maria was able to move her left leg and her left arm by herself. She was able to pull and push her left leg so strongly that the doctor was encouraged to ask her if she would like to try walking. She did not hesitate and said with a clear voice, “Yes. I would like to try.” While she was walking back and forth in her room exercising her leg with the assistant helping, she kept saying, “Thank you, thank you so much for this miracle.” In this case, the hemiplegia was caused by cerebral hemorrhage, which has the worst prognosis for the sequelae of stroke, compared to cerebral embolism and cerebral thrombosis. After cerebral hemorrhage, the patient should get acupuncture treatment as soon as his or her condition is stable. The earlier the patient gets treatment, the better the prognosis will be.

Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia is a chronic disorder characterized by diffuse or specific pain in muscles, ligaments, tendons, joints, or bone. Also, patients experience multiple tender points and fatigue. Fibromyalgia affects more females than males. Symptoms and signs can vary depending on stress, physical activity, weather changes, or even the time of day. Common symptoms and signs include widespread pain and stiffness, fatigue and sleep disturbances, heightened sensitivity of the skin, headache and facial pain, irritable bowel syndrome, weakness of limbs, muscle spasms, and impaired concentration and short-term memory.9 The degree of symptoms may also vary greatly from day to day with periods of flare-ups or remissions.

Case Report 5—Fibromyalgia

Before scalp acupuncture, Judy had lost all hope of ever having her old health back, but after 20 treatments, Judy hardly experienced any pain . She had lower back pain occasionally but it was manageable; and receiving scalp acupuncture treatments every 4 to 6 weeks kept the pain under control. She said she was also glad to be able to live without painkillers anymore, and did not need to rely on drugs just to get through the day. In addition to pain relief, Judy reported that her immune system was stronger than ever, and she rarely suffered from colds or flu since receiving scalp acupuncture treatments.

Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a progressive disease of the central nervous system in which communication between the brain and other parts of the body is disrupted. There are multiple scars on the myelin sheaths, which comprise a fatty layer surrounding and protecting the neurons of the brain and spinal cord. Myelin allows for the smooth, high-speed transmission of electrochemical messages between the brain, the spinal cord, and the rest of the body. When myelin is destroyed or damaged, the ability of the nerves to conduct electrical impulses to and from the brain is disrupted, which causes the various symptoms of MS. Approximately 300,000 people in the United States and 2.5 million people worldwide suffer from MS. It primarily affects adults, with age of onset typically between 20 and 40 years, and is twice as common in women than in men. The effects of MS can range from relatively benign in most cases to various degrees of disability. However, the symptoms for some are devastating. Symptoms and signs of MS vary widely depending on the location of the affected myelin sheaths. Common symptoms may include numbness, tingling or weakness in one or more limbs, partial or complete loss of vision, double or blurring of vision, tremor, loss of balance and mobility, unsteady gait, fatigue, and dizziness. Some patients also might develop muscle stiffness or spasticity, paralysis, slurred speech, dysfunction of bladder or bowel, depression, and cognitive impairment. MS is unpredictable and varies in severity. In some patients it is a mild illness, but it can lead to permanent disability in others. In the worst cases, patients with MS may be unable to write, speak, or walk.

Scalp acupuncture has been proved to have the most success in the treatment of MS and other central nervous system damage when compared to other acupuncture modalities including the ear, body, and hand. Scalp acupuncture not only can improve the symptoms, the patient’s quality of life, and slow the progression of physical disability, but also it can reduce the number of relapses. Scalp acupuncture treatment for MS has had much success in reducing numbness and pain, decreasing spasms, improving weakness and paralysis of limbs, and improving balance. Many patients also have reported that their bladder and bowel control, fatigue and overall sense of well-being significantly improved after treatment. Recent studies have shown that scalp acupuncture could be an effective modality in controlling MS. Scalp acupuncture often produces remarkable results after just a few needles are inserted.10 It usually relieves symptoms immediately, and sometimes it takes only several minutes to achieve remarkable results.

Case Report 9—Dizziness and Vertigo

A 60-year-old female received scalp acupuncture treatment. After the first symptoms occurred at age 20, the patient was finally diagnosed with MS in 1994. Her major symptoms were dizziness and vertigo accompanied by temple headaches that gradually became worse over the next 7 years. Sometimes her vertigo was so severe that she felt as if the whole room was spinning violently, which caused her to fall down easily even when she was just standing. Her quality of life was completely diminished and she had to spend whole days flat on her back with her eyes closed to avoid any movement of her head. The onset of dizziness and vertigo were exacerbated whenever she changed her position in bed or even slightly moved her head.

Conclusion

The authors hope that acupuncture practitioners, teachers, and students will benefit from the knowledge and experience imparted in this chapter. It is intended to serve as the basis for further teaching, practice, and research. For more detailed information on scalp acupuncture please see the authors’ new book, Chinese Scalp Acupuncture, that will be published on November 2011 by Blue Poppy Press in Boulder, Colorado. They can be contacted by visiting their website www.scalpacumaster.com or call their clinic in Albuquerque, New Mexico at 505-822-9878.

1. Jiao Shunfa. Head Acupuncture. Bejiing: Forign Languages Press; 1993. 17-22

2. Frank Lampe, Suzanne Snyder, Jason Hao. “DOM: Pioneering The Use of Scalp Acupuncture to Transform Healing”. Alternative Therapies. MAR/APR. 2009;15(2):62-71.

3. McMillan Brett B. “Easing the Pain, Acupuncture Program Looks to help Relieve Discomfort of Troops”. Stripe. February 17, 2006:1.

4. John O’Connor, Dan Bensky. Acupuncture A Comprehensive Text. Seattle: Eastland Press; 1981. 498-501

5. Hal Blumenfeld. Neuroanatomy Through Clinical Cases. Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinauer Associates, Inc; 2002. 28-29

6. Van Heertum Ranalk L., Tikofsky Ronald S. Functional Cerebral SPECT and PET Imaging, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott William & Wilkins; 2000. 62–63

7. Orhan Arslan. Neuroanatomical Basis of Clinical Neurology. New York: The Parthenon Publishing Group Inc; 2001. 335

8. Jason Hao, Linda Hao. “Treatment of Phantom Pain by Scalp acupuncture”. Acupuncture Today. September, 2006;7(9):10-11.

9. Shi Lingzhi, Hao Jishun. Treatment of Fibromyalgia by Eight-needle Penetrating Techniques”. Chinese Journal of Information on Traditional Chinese Medicine. Feb 2005;12(2):64.

10. Jason Hao, Linda Hao. “Treatment of Multiple Sclerosis By Scalp Acupuncture. Acupuncture Today. April 2008;9(4):12-13.