CHAPTER 6 The Technique and Art of the Physical Examination of the Adult and Adolescent Hip

The technique of physical examination

A vast number of tests exist for the examination of the hip, and it is not necessary to include them all in a single evaluation. Therefore, components of the examination can be classified as basic, which should always be included, and specific, which should be used as needed to define a specific diagnosis or combination of diagnoses. The most common examinations as determined by the MAHORN Group are shown in Table 6-1. This is a consensus among hip specialists to identify basic and specific components of the physical examination.

Table 6–1 Most Frequent Tests Performed by Mahorn Group Specialists

| Standing Position | Supine Position |

| Gait | Flexion ROM |

| Single Leg Stance Phase Test | Flexion Internal Rotation |

| Laxity | Flexion External Rotation |

| Lateral Position | FADDIR Test |

| Palpation | Palpation |

| Passive Adduction Test | FABER Test |

| Abductor Strength | Straight Leg Raise Against Resistance |

| Prone Position | Strength Assessment |

| Femoral Anteversion Test | Passive Supine Rotation |

| DIRI | |

| DEXRIT |

The standing examination of the hip

In addition to body habitus and gait evaluation, the Single Leg Stance Phase test is performed during the standing evaluation of the hip. The Single Leg Stance Phase test is performed on both legs, with the nonaffected leg examined first to establish a baseline reference for the patient’s function. As the patient lifts and holds one foot off the ground for 6 to 8 seconds, the contralateral hip abductor musculature and neural loop of proprioception are being tested. The pelvis will tilt toward the unsupported side if the musculature is weak or if the neural loop of proprioception is disrupted. Normal dynamic midstance translocation is 2 cm during a normal gait pattern; therefore, the rationale is that a shift of more than 2 cm constitutes a positive Single Leg Stance Phase test. Table 6-2 provides an outline of the standing examination.

| Test/Assessment | Association |

|---|---|

| Spinal Alignment | Shoulder height, iliac crest height, lordosis, scoliosis, leg length discrepancy, trunk flexion and side-to-side ROM |

| Ligamentous Laxity | Check for laxity in other joints: thumb, elbows, shoulders, or knee |

| Single Leg Stance Phase Test | Proprioception mechanism disruption, strength of abductor musculature |

| Gait | |

| Abductor Deficient Gait | Proprioception mechanism disruption, weak abductor strength |

| Pelvic Rotational Wink | Contracted hip flexor, excessive femoral anteversion, laxity of the hip capsule (anterior), intra-articular pathology |

| Foot Progression Angle with Excessive External Rotation | Femoral retroversion, excessive acetabular anteversion, abnormal torsional parameters, effusion, ligamentous injury |

| Foot Progression Angle with Excessive Internal Rotation | Excessive femoral anteversion, acetabular retroversion, abnormal torsional parameters |

| Short Leg Limp | Iliotibial band pathology, uneven leg lengths |

The seated examination of the hip

The loss of internal rotation is one of the first signs of the possibility of an intra-articular disorder; therefore, an important assessment is the internal and external rotation in the seated position. The seated position ensures that the ischium is square to the table, thus providing sufficient stability at 90 degrees of hip flexion and a reproducible platform for accurate rotational measurement. Passive internal and external rotation testing is performed gently and compared between the two sides. Seated rotation range of motion is also compared and contrasted with the extended position of the hip. Table 6-3 provides normal internal and external rotation ranges of motion in these positions.

| Test/Assessment | Association |

|---|---|

| Neurological Assessment | Symmetrical sensation of the sensory nerves originating from the L2-S1 levels, deep tendon reflexes: patellar and Achilles tendons |

| Straight Leg Raise | Symptoms of radicular neuropathy |

| Vascular Assessment | Dorsalis pedis pulse and posterior tibial artery pulse |

| Lymphatic Assessment | Inspection of the skin for swelling, scarring, or side to side asymmetry |

| Seated Piriformis Stretch Test | Deep gluteal syndrome, sciatic nerve entrapment, piriformis syndrome |

| Hip internal rotation ROM | Bilateral assessment noting any side-to-side differences. Normal between 20 ° and 35 ° |

| Hip external rotation ROM | Bilateral assessment noting any side-to-side differences. Normal between 30 ° and 45 ° |

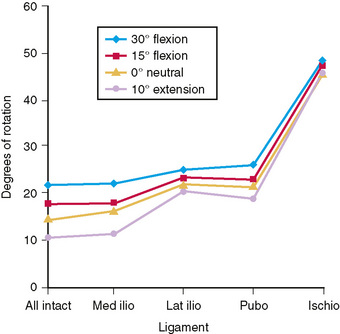

Musculotendinous, ligamentous, and osseous control of internal and external rotation is complex (Figure 6-1); therefore, any differences in seated positions as compared with extended positions may raise the question of ligamentous abnormality as compared with osseous abnormality. Sufficient internal rotation is important for proper hip function; there should be at least 10 degrees of internal rotation during the midstance phase of the normal gait. The loss of internal rotation at the hip can be related to diagnoses such as arthritis, effusion, internal derangements, slipped capital femoral epiphysis, and muscular contracture. Pathology related to femoroacetabular impingement or to rotational constraint from increased or decreased femoroacetabular anteversion can result in significant differences between the sides. An increased internal rotation in combination with a decreased external rotation may indicate excessive femoral anteversion, although the hip capsular function will require further assessment; this is correlated with the radiographic findings. Table 6-3 provides an outline of the seated examination.

The supine examination of the hip

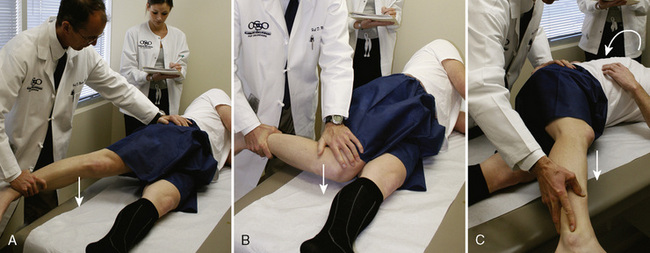

Tests—including those of flexion, adduction, and internal rotation—are useful for the detection of impingement or intra-articular pathology. The degree of flexion required in this position of adduction and internal rotation depends on the degree of impingement and the type and location of the impingement. The degree of hip flexion with the amount of pressure of the internal rotation is taken on a case-by-case basis, depending upon the function required of the patient as well as the patient’s complaint. The traditional McCarthy test elicits a pop when the examined hip is circumducted in this flexed, adducted, internally or externally rotated position while the contralateral leg is held in flexion, as with the Hip Flexion Contracture test. The Dynamic Internal Rotatory Impingement test (DIRI) and Dynamic External Rotatory Impingement test (DEXRIT) (video) are performed as a traditional McCarthy test; however, a positive test is noted by recreation of the patient’s pain. It is important that the zero set point of the pelvis is obtained by having the patient hold the nonaffected leg in flexion beyond 90 degrees. The DEXRIT (Figure 6-2) is performed passively by rotating the examined hip in a wide arc from the flexed position to an abducted, extended position while simultaneously externally rotating the femur. The DIRI test is performed by rotating the hip conversely in a wide arc from a slightly abducted, flexed position into a flexed, adducted, and internally rotated position. The reproduction of these dynamic supine tests is interoperatively helpful for assessment and treatment.

Other useful tests may include the Tinel’s test of the femoral nerve. The Tinel’s test is found to be positive with hip-flexion contractures of more than 25 degrees. A heel strike test (video) is performed by striking the heel abruptly, which is indicative of some type of trauma or stress fracture. The Passive Supine Rotation test (video) involves passive internal and external rotation of the femur, with the leg lying in an extended or slightly flexed position. The Passive Supine Rotation test is performed bilaterally, and any side-to-side differences with regard to this maneuver can alert the examiner to the presence of laxity or effusion. Table 6-4 provides an outline of several supine examinations and their possible associations.

| Test/Assessment | Association |

|---|---|

| Hip ROM (passive) | Hip flexion (normal 100-110 °), abduction (normal 45 °), and adduction (normal 20-30 °), ROM until a firm endpoint or pain |

| Flexion, adduction, internal rotation (FADDIR) | FAI-anterior, anterior labral tear |

| Hip Flexion Contracture Test | Contracted hip flexor (psoas), neuropathy of the femoral nerve, intra-articular pathology, abdominal etiology |

| Flexion, abduction, external rotation (FABER) | Differentiation of hip pathology from lumbar or sacroiliac joint pathology |

| Dynamic Internal Rotatory Impingement Test (DIRI) | FAI—anterior, anterior labral tear |

| Dynamic External Rotatory Impingement Test (DEXRIT) | FAI—superior, superior labral tear |

| Posterior Rim Impingement Test | FAI—posterior, posterior labral tear |

| Passive Supine Rotation Test | Bilateral assessment noting any side-to-side differences, laxity, effusion, synovitis, internal derangement |

| Heel Strike | Trauma, femoral stress fracture |

| Straight Leg Raise Against Resistance | Intra-articular pathology as the psoas places pressure on the labrum, strength of the hip flexors and psoas |

| Palpation | |

| Abdomen | Fascial hernia (also palpate with abdominal contraction), associated gastrointestinal/genitourinary pathology |

| Pubic Symphysis | Osteitis pubis, calcification, fracture, trauma |

| Adductor Tubercle | Adductor tendonitis |

The lateral examination of the hip

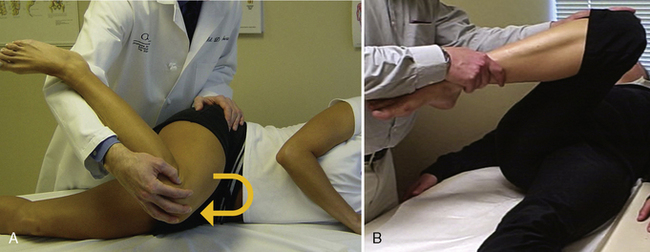

The lateral examination places the hip in an excellent position for further musculotendinous, ligamentous, and osseous evaluations. The lateral examination begins with the patient on the contralateral side for palpating the areas of the supra-SI and SI joints, the muscles of abduction, and, in particular, the origin of the gluteus maximus as it inserts along the lateral border of the sacrum and the most posterior aspect of the ilium. The next point of palpation is the ischium for detecting hamstring avulsions or tendonitis. Finally, the piriformis is palpated for any sign of tenderness, along with the abductor musculature, which includes the gluteus maximus, the gluteus medius, the gluteus minimus, and the tensor fascia lata. An active piriformis test (Figure 6-3; video) is performed by having the patient push the heel down into the table, thus abducting and externally rotating the leg against resistance, while the examiner monitors the piriformis. The Active Piriformis test is similar to Pace’s sign performed in the seated position useful for evaluating deep gluteal syndrome.

Tests of Passive Adduction (Figure 6-4) are performed with the leg in three positions: extension (the tensor fascia lata contracture test), neutral (the gluteus medius contracture test), and flexion (the gluteus maximus contracture test). A traditional Ober test is performed with the hip in extension or neutral and then in adduction toward the table. Evaluation of gluteus medius tension is achieved by the release of the iliotibial band with knee flexion, and the hip should be able to be adducted down toward the table. Any restrictions of these motions are recorded. When performing the gluteus maximus contracture test, the shoulder is rotated toward the side of the table, with the hip flexed and knee extended. If adduction cannot occur in this position, the gluteus maximus portion is contracted. The hip should be able to freely come into a full adducted position, and any restriction of the gluteus maximus is recognized. The gluteus maximus is balanced with the tensor fascia lata anteriorly. If the hip does not come beyond the midline in the longitudinal axis of the torso, it is graded as 3+ restriction above the torso, 2+ at the midline, and 1+ restriction below. A clear delineation of the exact area of restriction will help to direct physical therapy and treatment options.

Next is the passive assessment of flexion, adduction, and internal rotation, which is performed in a dynamic manner. The critical factor is the way in which the leg is held (Figure 6-5). The examiner holds the monitoring hand in and around the superior aspect of the hip, with the lower leg cradled on the forearm with the knee upon the hand. The hip is then brought into flexion and adduction and internally rotated. Any reproduction of the patient’s complaint and the degree of impingement are noted. FADDIR can also be performed in the supine position.

The lateral rim impingement test (video) is performed with the hip passively abducted and externally rotated. Any type of recreation of a posterior or lateral rim complaint or impingement can be precipitated in this position. Other tests may include the extension, abduction, and external rotation test (as with the apprehension test performed on the shoulder) for the detection of any type of anterior capsular laxity or injury. Forward pressure is applied to the posterior aspect of the hip, and the recreation of the patient’s complaint pain is a positive test. Current research suggests that this position specifically releases the teres ligament. Table 6-5 provides an outline of several lateral examinations and their possible associations.

| Examination | Assessment/Association |

|---|---|

| Flexion, Adduction, Internal Rotation (FADDIR) | FAI—anterior, anterior labral tear |

| Lateral Rim Impingement | FAI—lateral, lateral labral tear, instability |

| Tests of Passive Adduction | |

| Tensor Fascia Lata Contracture Test | Contracture of the tensor fascia lata muscle |

| Gluteus Medius Contracture Test | Contracture of the gluteus medius muscle, torn gluteus medius (decreased strength with knee flexion, suspect tear) |

| Gluteus Maximus Contracture Test | Contracture of the gluteus maximus, iliotibial band contribution, decreased abductor strength |

| Palpation | |

| Greater Trochanter | Greater trochanteric bursitis |

| Sacroiliac Joint | Differentiation of hip and back pathology |

| Maximus Origin | Tendonitis of the gluteus maximus origin |

| Ischium | Tendonitis of the biceps femoris muscle, avulsion fracture, ischial bursitis |

The prone examination of the hip

The Rectus Contracture test is performed with the patient in the prone position, and the lower extremity is flexed toward the gluteus maximus. Any raise of the pelvis or restriction of hip-flexion motion is indicative of rectus femoris contracture. Table 6-6 provides an outline of the prone examination.

| Test/Assessment | Association |

|---|---|

| Rectus Contracture Test | Contracture of the rectus femoris muscle |

| Femoral Anteversion Test | Femoral anteversion (normal between 10-20 °), ligamentous injury, increased laxity |

| Palpation | |

| Supra-SI | Mechanical conflict with the transverse process and ilium |

| SI | Inflammation of the SI joint |

| Gluteus Maximus Insertion | Tendonitis of the gluteus maximus insertion |

| Spine | Mechanical pathology related to the spine (facets) |

| With Lumbar Hyperextension | Help to identify location of spinal pain; if positive, place in supine position with knee flexion |

Specific tests

Further specific tests are useful for the assessment of complex hip pathology. Shown in the video are several tests performed by hip specialists. Dr. Marc Philippon (Figure 6-6) demonstrates the posterior rim impingement test in which the recreation of pain is a positive test. Dr. Jon Sekiya performs the passive supine rotation bilaterally for detecting capsular laxity of the left leg. Also shown is the scour test, which the examiner performs similarly to DIRI test but that involves the placement of pressure on the knee during the assessment for detecting interarticular congruence. Dr. Michael Leunig has the patient perform a bicycle test while monitoring the iliotibial band for the detection of coxa sultans externus. The fulcrum test (performed by the author) is performed with the examiner’s knee placed under the patient’s knee, thus acting as the fulcrum. The patient then performs a straight-leg test against resistance. The importance of bilateral assessment is demonstrated by Dr. Bryan Kelly when performing the straight-leg test against resistance. RobRoy Martin, PhD, demonstrates the foveal distraction test. Interarticular pressure is alleviated by gently pulling the leg away from the body. Both the relief of pain and the recreation of pain will help to delineate an extra-articular pathology from an intra-articular pathology. Also shown is the FABER test, which is described in the section entitled “The Supine Examination of the Hip.” The Seated Piriformis Stretch test is performed in the seated position with the hip at 90° of flexion. The examiner extends the knee and passively moves the flexed hip into adduction with internal rotation while palpating 1cm lateral to the ischium (middle finger) and proximally at the sciatic notch (index finger). A positive test is the recreation of the posterior pain and may indicate deep gluteal syndrome.

Summary

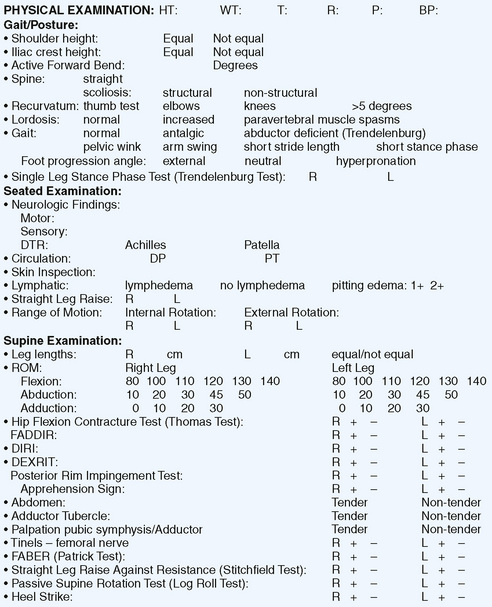

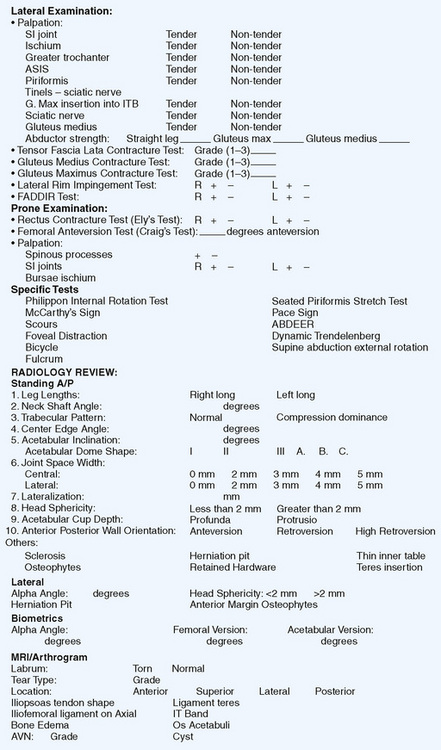

A general overview of the hip examination form is provided in Figure 6-7. Further diagnostic tests (e.g., x-ray, magnetic resonance imaging and arthrography, injection tests) will also aid in the diagnosis of hip pathology. The use of a formalized, reproducible examination will help identify the hip as the source of pain and comorbidities in a timely fashion.

Annotated references and suggested readings

McCarthy J., Noble P., Aluisio F.V., Schuck M., Wright J., Lee J.A. Anatomy, pathologic features, and treatment of acetabular labral tears. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003:38-47.

Hoppenfeld S., Hutton R. Physical examination of the hip and pelvis. In: Hoppenfeld S., Hutton R., editors. Physical Examination of the Spine and Extremities. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall;; 1976:143-169.

Reider B. The Orthopaedic Physical Examination. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders, 1999.

Byrd J. Operative Hip Arthroscopy, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer, 2005.

Braly B.A., Beall D.P., Martin H.D. Clinical examination of the athletic hip. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25:199-210. vii

Martin H.D. Clinical examination of the hip. Operative Techniques in Orthopaedics. 2005;15:177-181.

Biering-Sorensen F. Physical measurements as risk indicators for low-back trouble over a one-year period. Spine. 1984;9:106-119.

Brown M.D., Gomez-Marin O., Brookfield K.F., Li P.S. Differential diagnosis of hip disease versus spine disease. Clin Orthop Relat Res.. 2004:280-284.

Giles L.G., Taylor J.R. Low-back pain associated with leg length inequality. Spine. 1981;6:510-521.

DeAngelis N.A., Busconi B.D. Assessment and differential diagnosis of the painful hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003:11-18.

Scopp J.M., Moorman C.T. 3rd. The assessment of athletic hip injury. Clin Sports Med.. 2001;20:647-659.

Kim Y.T., Azuma H. The nerve endings of the acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995:176-181.

Martin H.D., Savage A., Braly B.A., Palmer I.J., Beall D.P., Kelly B. The function of the hip capsular ligaments: a quantitative report. Arthroscopy. 2008;24:188-195.

Torry M.R., Schenker M.L., Martin H.D., Hogoboom D., Philippon M.J. Neuromuscular hip biomechanics and pathology in the athlete. Clin Sports Med. 2006;25:179-197. vii

Beall D.P., Sweet C.F., Martin H.D., Lastine C.L., Grayson D.E., Ly J.Q., et al. Imaging findings of femoroacetabular impingement syndrome. Skeletal Radiol. 2005;34:691-701.

Ganz R., Parvizi J., Beck M., Leunig M., Notzli H., Siebenrock K.A. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003:112-120.

Ito K., Minka M.A.2nd, Leunig M., Werlen S., Ganz R. Femoroacetabular impingement and the cam-effect. A MRI-based quantitative anatomical study of the femoral head-neck offset. J Bone Joint Surg. 2001;83:171-176.

Martin H.D., Kelly B.T., Leunig M., Philippon M.J., Clohisy J.C., Martin R.L., Sekiya J.K., Pietrobon R., Mohtadi N.G., Sampson T.G., Safran M.R. The pattern and technique in the clinical evaluation of the adult hip: the common physical examination tests of hip specialists. Arthroscopy. 2010;26:161-172.

Martin R.L., Enseki K.R., Draovitch P., Trapuzzano T., Philippon M.J. Acetabular labral tears of the hip: examination and diagnostic challenges. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:503-515.

O’Leary J.A., Berend K., Vail T.P. The relationship between diagnosis and outcome in arthroscopy of the hip. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:181-188.

Voos J.E., Rudzki J.R., Shindle M.K., Martin H., Kelly B.T. Arthroscopic anatomy and surgical techniques for peritrochanteric space disorders in the hip. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:1246, e5.

Above reference reviews the role of successful hip arthroscopy in peritrochanteric space disorders..