15

The menopause

Introduction

Human female fertility terminates relatively abruptly in middle-age. This seems to be rather a puzzle as, in evolutionary terms, those genes that ‘favour’ giving birth to as many offspring as possible, would be expected to proliferate. In other words, the genes of mothers who continued giving birth to children for as many years as they could would be expected to be successful. Human children, however, remain dependent on their mothers for many years after birth and, if mothers continued to reproduce until the end of their lives, they would be less able to support the later children to independent maturity. The incidence of congenital abnormality also increases with maternal age. This would be a waste of personal resources without genetic benefit, and would also limit the support such a mother could offer to her grandchildren, in whom she has a quarter-part genetic investment.

The flaw in this otherwise reasonable teleological argument, however, is that previously, the vast majority of women died long before reaching the current average age of menopause, thus diluting the role of longevity in the evolutionary process. The true reasons behind this process of ovarian failure, the menopause, are therefore not yet fully elucidated.

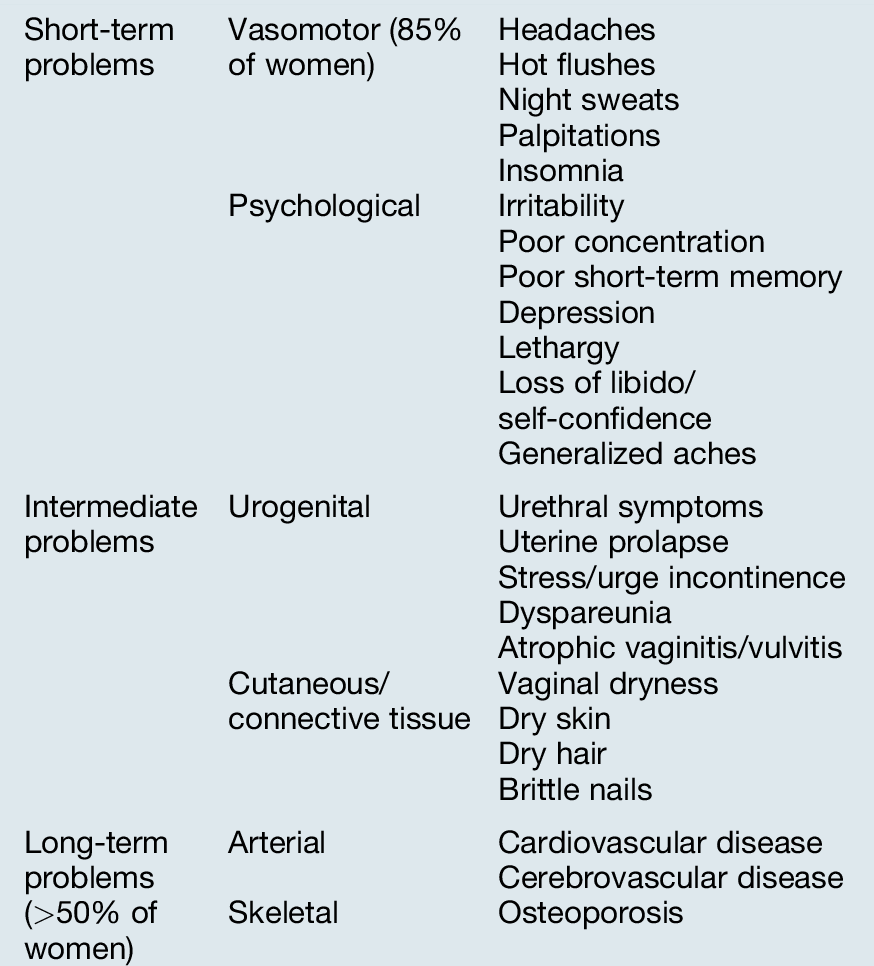

Menopause literally means ‘last menstrual period’ but the word is often used to cover the physiological changes that occur around this time. The fluctuating levels of oestrogen resulting from declining ovarian function lead to changes in a number of systems, and may give rise to significant symptoms. Although physiological, the menopause has important adverse long-term effects on health (Table 15.1) which can, in part, be offset by the use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT). The pros and cons of this treatment will be discussed in more detail and need to be carefully considered on an individual basis before treatment is started.

Physiology

The perimenopause (or climacteric) may begin months or years before the last menstrual period, and symptoms may continue for years afterwards. The median age at menopause in the UK is 50.8 years and it occurs when the supply of oocytes becomes exhausted. A newborn girl has over half a million oocytes in her ovaries: one-third of these disappear before puberty and most of the remainder are lost during reproductive life. In each menstrual cycle, some 20 or 30 primordial follicles begin to develop and most become atretic. As only about 400 cycles occur during an average woman’s lifetime, most oocytes are lost spontaneously through ageing, rather than through ovulation.

In premenopausal women, oestradiol is produced by the granulosa cells of the developing follicle, but, as the menopause approaches, this production becomes very variable. The proportion of anovulatory menstrual cycles increases and progesterone production declines. Pituitary production of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) rises because of diminishing negative feedback from oestrogen and other ovarian hormones, such as inhibin, but other pituitary hormones are not affected. Serum levels of FSH over 30 IU/L can be used clinically to clarify the diagnosis of the menopause (see below), although levels begin to rise significantly around the age of 38 even in normally cycling women. Anti-Müllerian hormone is a better marker of follicular reserve than FSH and is now used in medical practice.

Circulating androstenedione, mainly of adrenal origin, is converted by fat cells into oestrone, a less potent form of oestrogen than oestradiol. After the menopause, this is the predominant circulating oestrogen, rather than ovarian oestrogens.

Signs and symptoms (Table 15.1)

Vaginal bleeding

Irregular periods before the menopause are usually the result of anovulatory menstrual cycles, and, if irregular bleeding persists, endometrial assessment may be required to exclude the possibility of endometrial carcinoma. The menopause itself can be recognized only in retrospect after an arbitrary length of amenorrhoea, usually taken as 6 months or a year. Further vaginal bleeding after this is ‘postmenopausal’ and investigations may again be required. Approximately 10% of those with postmenopausal bleeding have a gynaecological malignancy.

Hot flushes

A ‘hot flush’ is an uncomfortable subjective feeling of warmth in the upper part of the body, usually lasting around 3 min. Approximately 50–85% of menopausal women experience such vasomotor symptoms, although only 10–20% seek medical advice. Flushes are sometimes accompanied by nausea, palpitations and sweating and may be particularly troublesome at night. They are thought to be of hypothalamic origin and may in some way be related to LH release. It is thought that a fall in oestrogen levels affects central neurotransmitters such as alpha-adrenergic or serotonergic systems, which in turn affect central thermoregulatory centres and LH-releasing neurons.

About 20% of women begin experiencing flushes while still menstruating regularly. Flushes slowly improve as the body adjusts to the new low oestrogen concentrations, but in approximately 25% of women, they continue for more than 5 years and can be extremely distressing, impairing quality of life. Exogenous oestrogen administration, in the form of HRT, is effective in relieving these symptoms in about 90% of cases.

Genitourinary atrophy

The genital system, urethra and bladder trigone are oestrogen-dependent and undergo gradual atrophy after the menopause. Thinning of the vaginal skin may cause dyspareunia and bleeding, and loss of vaginal glycogen causes a rise in pH, which can predispose to local infection. Urgency of micturition may result from atrophic change in the trigone. Unlike flushes, these atrophic symptoms may appear years after the menopause and do not improve spontaneously, although they respond well to a short course of local or systemic oestrogen.

Other symptoms

Some studies have suggested that many symptoms, including irritability and lethargy, can be improved by hormone therapy more effectively than by placebo. Most investigators, however, feel that the symptom of depression is not due directly to oestrogen withdrawal; although it has been reported that oestrogen treatment can improve the symptoms of depression. It is possible that this effect may be related to the indirect relief of specific symptoms, such as insomnia caused by night sweats.

Long-term effects

The menopause alters a woman’s susceptibility to breast cancer, cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis.

Breast cancer

Although the risk of breast cancer increases with increasing age, the rate of increase slows after the menopause. The risk of breast cancer is decreased if the menopause is premature and increased if it occurs late, such that a woman who has had a menopause in her late 50s has double the risk of breast cancer when compared with a woman who has had a menopause in her early 40s.

Cardiovascular disease

A premenopausal woman’s risk of developing coronary artery disease is less than one-fifth of that of a man of the same age; a sex difference that has disappeared by the age of 85 years. This has been assumed to indicate that oestrogens protect against vascular disease, but the phenomenon may be due to other risk factors affecting the male and to the fact that high-risk men die before they reach old age.

Studies looking at the effect of postmenopausal oestrogen therapy on cardiovascular disease suggest that unopposed oestrogen treatment may reduce the risk of ischaemic heart disease. More recent studies, however, looking at the incidence of subsequent myocardial infarction, have found no protective effect overall. However, starting combined HRT at the time of the natural menopause (i.e. around 50 years) does not seem to be associated with an increased incidence of cardiovascular events and may even be associated with a decrease, although this is uncertain. There is likely to be an adverse impact in women over 60 years of age at initiation of HRT.

Osteoporosis

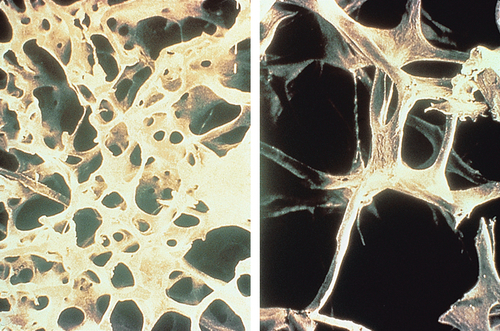

Bone resorption by osteoclasts is accelerated by the menopause (Fig. 15.1). Oestrogen receptors have been demonstrated on bone cells, and oestrogens have been shown to stimulate osteoblasts directly. Calcitonin and prostaglandins may also be involved as intermediate factors in the link between oestrogen and bone metabolism.

In the first 4 years after the menopause, there is an annual loss of 1–3% of bone mass, falling to 0.6% per year thereafter. This leads to an increased rate of fractures, particularly of the distal radius, the vertebral body and the upper femur, and one or more of these fractures will affect 40% of women over 65 years. Wedge compression fractures of the spine, leading to the so-called ‘dowager’s hump’ affect 25% of white women over 60 years (Fig. 15.2), and fractures of the hip have occurred in 20% of women by the age of 90 years. Women who are underweight have a higher risk of osteoporosis because of reduced peripheral conversion of androgens to oestrogen. Women of Afro-Caribbean origin have a smaller risk of osteoporosis than white or Asian women, as they have a greater initial bone mass.

Osteoporosis has important consequences for women and for health services. In the UK, over 35 000 postmenopausal women suffer femoral fractures every year and 17% of them die in hospital. HRT has a very significant benefit in reducing the incidence of osteoporosis and osteoporotic fractures.

Administration of oestrogen decreases fracture risk; however, it is not recommended as a first-line treatment, as the long-term risks (particularly stroke) are considered to outweigh the benefits.

Diagnosis

The menopause may be confused with premenstrual syndrome (PMS), depression, thyroid dysfunction, pregnancy and, rarely, phaeochromocytoma or carcinoid syndrome. Vasomotor symptoms may be caused by calcium antagonists and by antidepressive therapy, especially tricyclics.

The diagnosis of menopause is usually clinical and can only be made in retrospect after 6–12 months of amenorrhoea. If there is clinical confusion, there may be some value in checking the serum FSH level, which should be > 30 IU/L postmenopausally. Perimenopausally, the level may be normal, and it should be noted that FSH levels peak physiologically in mid-cycle, making it worth re-checking apparently high levels a second time. If there is diagnostic doubt about whether a woman is perimenopausal, especially over 45 years of age, a therapeutic trial of HRT may be considered. Absence of a satisfactory response suggests that symptoms are unrelated to low levels of oestrogen.

Hormonal therapy

Oestrogen supplementation is the basis of replacement therapy. Although progestogens may have a small role in relieving vasomotor symptoms, they are added to oestrogen to protect the endometrium and reduce the hyperplasia that would otherwise result. The oestrogens may be systemically administered as daily oral tablets, twice-weekly or weekly transdermal patches, or subcutaneous implants administered every 6–8 months. Daily nasal sprays, skin creams and 3-monthly vaginal rings are also used.

Whatever the route of administration, women who have not undergone hysterectomy should be placed on a regimen, which includes a progestogen to minimize the risk of endometrial cancer associated with unopposed oestrogen therapy as mentioned above. This advice applies also to women who have undergone endometrial resection. Women who have had a hysterectomy do not require a progestogen.

Oral preparations

The oral route may have a more beneficial effect than parenteral therapy on lipid profiles, leading to higher HDL and lower LDL levels, but it is potentially more thrombotic. Tablets may be given as an oestrogen-only preparation for those who have had a hysterectomy, or as a combined oestrogen–progestogen preparation for those who have not. The combined form may be administered cyclically or continuously.

Cyclical preparations, which usually lead to monthly withdrawal bleeds, are used perimenopausally, and the continuous combined preparations, the so-called ‘no-period’ HRT, are an option from more than 2 years after the last menstrual period. This continuous combined therapy is more convenient for the 80 + % who do not suffer unscheduled bleeding, but erratic bleeding beyond the first 6 months of treatment warrants further investigation.

Alternatives to these oestrogen–progesterone preparations are tibolone and raloxifene. Tibolone is a synthetic steroid with weak oestrogenic, progestogenic and androgenic effects, which may be started 2 years after periods have ceased in a similar way to the continuous combined preparations. Raloxifene, a synthetic selective oestrogen-receptor modulator (SERM), has oestrogenic effects on bone and lipid metabolism but has a minimal effect on uterine and breast tissue. It is therefore ineffective for controlling perimenopausal symptoms but it has a useful role in protecting against osteoporosis and it does not cause vaginal bleeding.

Transcutaneous administration

Transdermal patches are available as an unopposed oestrogen form, or as cyclical or continuous oestrogen–progestogen combinations. Skin reactions, ranging from hyperaemia to blisters, affect only a very small percentage of users.

The clinical advantage of transcutaneous administration is that it should avoid gastrointestinal side-effects, and minimize the effects on hepatic production of both lipoproteins and coagulation factors. Patches are usually applied to the buttock, and each patch lasts for between 3 and 7 days, depending on the formulation. This method appears to be as effective as oral preparations in treating symptomatic women and for the prevention of osteoporosis.

Percutaneous oestrogen gels are also available. A measured dose is rubbed into the skin and avoids the prolonged skin contact of patches. The same contraindications apply as for other unopposed oestrogens.

Subcutaneous implants

Oestradiol may be implanted in subcutaneous fat, usually in the lower abdomen, at intervals of no less than 5 or 6 months. The oestradiol level does not always fall away to baseline before symptoms recur and there is a risk of tachyphylaxis (persistent symptoms despite ever-increasing oestradiol levels) unless strict dose control is observed. Providing that pre-implant oestradiol levels are monitored, however, the risk of tachyphylaxis is minimized. Testosterone implants can be used where there is low libido.

Vaginal preparations

These include oestradiol tablets, low-dose oestradiol-releasing Silastic ring pessaries, and oestriol vaginal pessaries and vaginal cream. They are all useful in the treatment of atrophic vaginitis.

Risks and side-effects of hormone treatment

General

Nausea and breast tenderness occur in about 5–10% of patients. Uterine bleeding is less common with low-dose regimens and, in general, the lowest dose that controls symptoms should be used. Irregular bleeding should be investigated as appropriate. There is a slight risk of cholelithiasis, and there is a theoretical chance of glucose tolerance impairment.

Endometrial carcinoma

Unopposed therapy (i.e. oestrogen only) increases the incidence of endometrial cancer four-fold, and it should therefore be used only for those who have had a hysterectomy. The incidence is reduced to a relative risk of < 1.0 with opposed therapy (i.e. with the addition of progesterone for at least 10 days per cycle). The levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (Mirena) protects the endometrium effectively when used in conjunction with oestrogen-only HRT in postmenopausal women.

Breast cancer

A link between oestrogen treatment and breast cancer is biologically plausible because of the connection between late menopause and breast cancer, as noted above. There is a small increase in likelihood of having breast cancer with combined HRT after 5 years of use, although oestrogen alone in hysterectomized women does not have this adverse effect. It would thus seem likely that it is the progestogen that causes the increase in the incidence of breast cancer. There is no increased risk in those who stopped taking HRT more than 5 years previously. It may be that breast cancer diagnosed while on HRT is more curable.

Other cancers

The evidence of any adverse effect on other cancers, such as ovarian, is equivocal and any effect is likely to be very small.

Venous thromboembolic disease

There is an increased risk of venous thromboembolic disease in the first year of HRT treatment, with a relative risk of approximately 4.0 in the first 6 months and 3.0 in the second 6 months (baseline risk 1.3/1000 per year). There is apparently no increased risk in those taking it beyond 1 year. Routine pre-treatment screening for thrombophilia is not recommended, but it should be carried out in those with a personal or family history of venous thromboembolic disease. It is probable that transcutaneous administration of oestrogen is not associated with an increased risk of primary VTE as hepatic first pass metabolism is avoided.

Stroke

There is a significant increase in the likelihood of stroke in all age groups, although the impact is small in younger menopausal women, as the baseline risk of stroke is so low.

Contraindications to hormone treatment

Pregnancy, thromboembolic disease and a history of recurrent venous thromboembolism are recognized contraindications to HRT, as are liver disease and undiagnosed vaginal bleeding. Treated hypertension and other cardiovascular risk factors are probably not contraindications.

Use of oestrogen-containing HRT is widely considered to be contraindicated following breast carcinoma (including intraductal carcinoma) and following advanced endometrial carcinoma. There are also theoretical reasons why it should be avoided in those who have had ovarian cancer.

Duration of HRT

When oestrogens are given for vasomotor symptoms, they are generally continued for 2 or 3 years and then stopped. Whether to continue therapy beyond this time depends on whether symptoms recur and on a weighing up of the risks of osteoporosis against the potential side-effects, including breast cancer, for that particular individual.

Non-hormonal treatment

Drugs

Vasomotor symptoms may be reduced by clonidine, which acts directly on the hypothalamus, but in practice, it is of limited value as it is no more effective than placebo in randomized controlled trials. The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) have also been shown to be effective. Palpitations and tachycardia may be improved by beta-blockers. Sedatives, hypnotics and antidepressants may be helpful in the treatment of non-vasomotor symptoms.

Herbal preparations are taken by many women but conclusive evidence of their benefit is lacking.

The first-line treatment for osteoporosis is now a bisphosphonate and oestrogen is used only for those where this is inappropriate. In elderly women, supplementation with calcium, calcitonin and vitamin D reduces the risk of hip fractures. Moderate exercise may slow the rate of bone loss, though compliance with exercise programmes is often poor.

Psychological support

Some women with menopausal symptoms need only reassurance. Others may have particular stresses at this time of life, such as children leaving home, which may accentuate their perimenopausal symptoms. The marked placebo benefits in various studies show the importance of psychological support and a sympathetic ear.