Chapter 666 The Foot and Toes

666.1 Metatarsus Adductus

Metatarsus adductus is common in newborns and involves adduction of the forefoot relative to the hindfoot. When the forefoot is supinated and adducted, the deformity is termed metatarsus varus (Fig. 666-1). The most common cause is intrauterine molding, where the deformity is bilateral in 50% of cases. As with other intrauterine positional foot deformities, a careful hip examination should always be performed.

666.2 Calcaneovalgus Feet

Harish S. Hosalkar, David A. Spiegel, and Richard S. Davidson

666.3 Talipes Equinovarus (Clubfoot)

The positional clubfoot is a normal foot that has been held in a deformed position in utero and is found to be flexible on examination in the newborn nursery. The congenital clubfoot involves a spectrum of severity, while clubfoot associated with neuromuscular diagnoses or syndromes are typically rigid and more difficult to treat. Clubfoot is extremely common in patients with myelodysplasia and arthrogryposis (Chapter 674).

Clinical Manifestations

A complete physical examination should be performed to rule out coexisting musculoskeletal and neuromuscular problems. The spine should be inspected for signs of occult dysraphism. Examination of the infant clubfoot demonstrates forefoot cavus and adductus and hindfoot varus and equinus (Fig. 666-2). The degree of flexibility varies, and all patients exhibit calf atrophy. Both internal tibial torsion and leg-length discrepancy (shortening of the ipsilateral extremity) are observed in a subset of cases.

Alvarado DM, Aferol H, McCall K, et al. Familial isolated clubfoot is associated with recurrent chromosome 17q23.1q23.2 microduplications containing TBX4. Am J Hum Genetics. 2010;87:154-160.

Bridgens J, Kiely N. Current management of clubfoot (congenital talipes equinovarus). BMJ. 2010;340:308-312.

Canto MJ, Cano S, Palau J, et al. Prenatal diagnosis of clubfoot in low-risk populations: associated anomalies and long-term outcome. Prenatal Diag. 2008;28:343-346.

Chang CH, Kumar SJ, Riddle EC, et al. Macrodactyly of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:1189-1194.

Dobbs MB, Gurnett CA. Update on clubfoot: etiology and treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:1146-1153.

Herzenberg JE, Radler C, Bor N. Ponseti versus traditional methods of casting for idiopathic clubfoot. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:517-521.

Ippolito E, Fraracci L, Farsetti P, et al. The influence of treatment on the pathology of clubfoot. CT study at maturity. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:574-580.

Morcuende JA, Dolan LR, Dietz FR, et al. Radical reduction in the rate of extensive corrective surgery for clubfeet using the Ponseti method. Pediatrics. 2004;113:376-380.

Noonan KJ, Richards BS. Nonsurgical management of idiopathic clubfoot. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2003;11:392-402.

Offerdal K, Jebens N, Blaas HGK, et al. Prenatal ultrasound detection of talipes equinovarus in a non-selected population of 49 314 deliveries in Norway. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2007;30:838-844.

Paton RW, Choudry Q. Neonatal foot deformities and their relationship to developmental dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91:B655-B658.

Roye DPJr, Roye BD. Idiopathic congenital talipes equinovarus. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2002;10:239-248.

Sankar WN, Weiss J, Skaggs DL. Orthopaedic conditions in the newborn. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:112-122.

Steinman S, Richards BS, Faulks S, et al. A comparison of two nonoperative methods of idiopathic clubfoot correction: the Ponseti method and the French functional (physiotherapy) method. Surgical technique. Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(Suppl 2):299-312.

666.4 Congenital Vertical Talus

Congenital vertical talus is an uncommon foot deformity in which the midfoot is dorsally dislocated on the hindfoot. Approximately 40% are associated with an underlying neuromuscular condition or a syndrome (Table 666-1); although the remaining 60% had been thought to be idiopathic, there is increasing evidence that some of these may be related to single gene defects. Neurologic causes include myelodysplasia, tethered cord, and sacral agenesis. Other associated conditions include arthrogryposis, Larsen syndrome, and chromosomal abnormalities (trisomy 13-15, 19). Depending on the age at diagnosis, the differential diagnosis might include a calcaneovalgus foot, oblique talus (talonavicular joint reduces passively), flexible flatfoot with a tight Achilles tendon, and tarsal coalition.

Table 666-1 ETIOLOGIES OF CONGENITAL VERTICAL TALUS

CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM AND SPINAL CORD

MUSCLE

CHROMOSOMAL ABNORMALITY

KNOWN GENETIC SYNDROMES

From Alaee F, Boehm S, Dobbs M: A new approach to the treatment of congenital vertical talus, J Child Orthop 1:165–174, 2007.

Clinical Manifestations

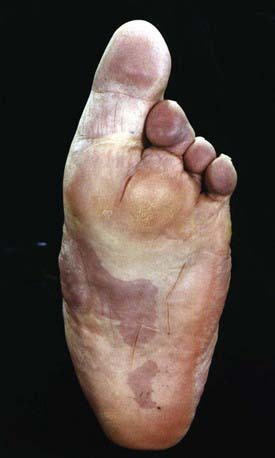

Congenital vertical talus has also been described as a rocker-bottom foot (Fig. 666-3) or a Persian slipper foot. The plantar surface of the foot is convex, and the talar head is prominent along the medial border of the midfoot. The fore part of the foot is dorsiflexed (dorsally dislocated on the hindfoot) and abducted relative to the hindfoot, and the hindfoot is in equinus and valgus. There is an associated contracture of the anterolateral (tibialis anterior, toe extensors) and the posterior (Achilles tendon, peroneals) soft tissues. The deformity is typically rigid. A thorough physical examination is required to identify any coexisting neurologic and/or musculoskeletal abnormalities.

Alaee F, Boehm S, Dobbs MB. A new approach to the treatment of congenital vertical talus. J Child Orthop. 2007:1165-1174.

Mazzocca AD, Thomson JD, Deluca PA, et al. Comparison of the posterior approach versus the dorsal approach in the treatment of congenital vertical talus. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:212-217.

666.5 Hypermobile Pes Planus (Flexible Flatfeet)

Radiographic Evaluation

Routine radiographs of asymptomatic flexible flatfeet are usually not indicated. Weight-bearing radiographs (AP and lateral) are required to assess the deformity. On the AP radiograph, there is widening of the angle between the longitudinal axis of the talus and the calcaneus, indicating excessive heel valgus. The lateral view shows distortion of the normal straight-line relationship between the long axis of the talus and the 1st metatarsal, with a sag either of the talonavicular or naviculocuneiform joint, resulting in flattening of the normal medial longitudinal arch (Fig. 666-4).

Evans AM. The flat-footed child—to treat or not to treat: what is the clinician to do? J Am Podiatr Med Assoc. 2008;98:386-393.

Giannini BS, Ceccarelli F, Benedetti MG, et al. Surgical treatment of flexible flatfeet in children: a four-year follow-up study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:78-79.

Lin CJ, Lai KA, Kuan TS, et al. Correlating factors and clinical significance of flexible flatfeet in preschool children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:378-382.

666.6 Tarsal Coalition

Harish S. Hosalkar, David A. Spiegel, and Richard S. Davidson

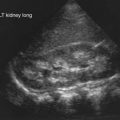

Radiographic Evaluation

AP and lateral weight-bearing radiographs and an oblique radiograph of the foot should be obtained (Table 666-2). A calcaneonavicular coalition will be seen best on the oblique radiograph. The lateral radiograph might show elongation of the anterior process of the calcaneus, known as the anteater sign. A talocalcaneal coalition may be seen on a Harris (axial) view of the heel. On the lateral radiograph, there may be narrowing of the posterior facet of the subtalar joint, or a C-shaped line along the medial outline of the talar dome and the inferior outline of the sustentaculum tali (C sign). Beaking of the anterior aspect of the talus on the lateral view is common and results from an alteration in the distribution of stress. This finding does not imply the presence of degenerative arthritis. Irregularity in the subchondral bony surfaces may be seen in patients with a cartilaginous coalition, in contrast to a well-formed bony bridge in those with an osseous coalition.

Table 666-2 RADIOGRAPHIC SECONDARY SIGNS ASSOCIATED WITH TARSAL CONDITIONS

From Slovis TL, editor: Caffey’s pediatric diagnostic imaging, ed 11, vol 2, Philadelphia, 2008, Mosby, p 2604.

A fibrous coalition might require additional imaging studies to diagnose. Plain films may be diagnostic, but a CT scan is the imaging modality of choice when a coalition is suspected (Fig. 666-5). In addition to securing the diagnosis, this study helps to define the degree of joint involvement in patients with a talocalcaneal coalition. Coalitions are uncommon, but >1 tarsal coalition may be observed in the same patient.

666.7 Cavus Feet

Harish S. Hosalkar, David A. Spiegel, and Richard S. Davidson

Cavus is a deformity involving plantar flexion of the forefoot or midfoot on the hindfoot and can involve the entire forepart of the foot or just the medial column. The result is an elevation of the longitudinal arch (Fig. 666-6), and a deformity of the hindfoot often develops to compensate for the primary forefoot abnormality. Familial cavus can occur, but most patients with this deformity have an underlying neuromuscular etiology. The initial goal is to rule out (and treat) any underlying causes. These diagnoses can relate to abnormalities of the spinal cord (occult dysraphism, tethered cord, poliomyelitis, myelodysplasia, Friedrich ataxia) and peripheral nerves (hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies such as Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, Dejerine-Sottas disease, Refsum disease). A unilateral cavus foot is most likely to result from an occult intraspinal anomaly, and bilateral involvement usually suggests an underlying nerve or muscle disease. Cavus is commonly observed in association with a hindfoot deformity. In cavovarus, which is the most common deformity in patients with the hereditary motor and sensory neuropathies, progressive weakness and muscle imbalance result in plantar flexion of the 1st ray or medial column. For the foot to land flat, the hindfoot must roll into varus. With equinocavus, the hindfoot is in equinus; in calcaneocavus (usually seen in polio or myelodysplasia), the hindfoot is in calcaneus (excessive dorsiflexion).

666.8 Osteochondroses and Apophysitis

Harish S. Hosalkar, David A. Spiegel, and Richard S. Davidson

Osteochondroses are acquired focal disorders of ossification involving epiphyses, apophyses, and other epiphyseal equivalents. Idiopathic avascular necrosis is rarely observed in the tarsal navicular (Köhler disease) or the 2nd or 3rd metatarsal head (Freiberg infraction). Köhler disease (Fig. 666-7) typically appears in children around age 5 or 6 yr and is 3-fold more common in boys than girls. Freiberg infraction is more common in girls and typically occur between ages 8 and 17 yr. Thess are generally self-limited conditions that commonly result in activity-related pain, which can at times be disabling. The treatment is based on the degree of symptoms and commonly includes restriction of activity. For patients with Köhler disease, a short leg cast (6-8 wk) can provide significant relief. Patients with Freiberg infraction can benefit from a period of casting and/or shoe modifications such as a rocker-bottom sole, a stiff-soled shoe, or a metatarsal bar. Degenerative changes occasionally occur following the gradual healing process, and surgical intervention is required in a subset of cases. Procedures have included joint debridement, bone grafting, redirectional osteotomy, subtotal or complete excision of the metatarsal head, and joint replacement.

666.9 Puncture Wounds of the Foot

Harish S. Hosalkar, David A. Spiegel, and Richard S. Davidson

Most puncture wound injuries to the foot may be adequately managed in the emergency department. Treatment involves a thorough irrigation and a tetanus booster, if appropriate; many clinicians recommend antibiotics. Using this approach, most children heal without a complication. A subset of patients develop cellulitis, most often due to Staphylococcus aureus (Chapter 174), and require intravenous antibiotics with or without surgical drainage. Deep infection is uncommon and may be associated with septic arthritis, osteochondritis, or osteomyelitis. The most common organisms are S. aureus and Pseudomonas (Chapter 197); the treatment involves a thorough surgical debridement followed by a short (10-14 days) course of systemic antibiotics. Plain radiographs demonstrate any metallic fragments, but ultrasonography may be necessary to identify glass or wooden objects. Routine exploration and removal of foreign bodies is not required, but it may be necessary when symptoms are present, with recurrences, or when an infection is suspected. Pain and/or gait disturbance is more likely with superficial objects under the plantar surface of the foot. One special situation occurs when a puncture wound from a nail comes through an old sneaker. There is a high risk of a pseudomonal infection, and thorough irrigation and debridement under general anesthesia followed by systemic antibiotics for 10-14 days should be considered.

666.10 Toe Deformities

Juvenile Hallux Valgus (Bunion)

Radiographic Evaluation

Weight-bearing AP and lateral radiographs of the feet are obtained. On the AP view, common measurements include the angular relationships between the 1st and 2nd metatarsals (intermetatarsal angle, <10 degrees is normal) and between the 1st metatarsal and the proximal phalanx (hallux valgus angle, <25 degrees is normal) (Fig. 666-8). The orientation of the 1st metatarsal-medial cuneiform joint is also documented. On the lateral radiograph, the angular relationship between the talus and the 1st metatarsal helps to identify a midfoot break associated with pes planus. Radiographs are more helpful in surgical planning than in establishing the diagnosis.

Syndactyly

Syndactyly involves webbing of the toes, which may be incomplete or complete (extends to the tip of the toes), and the toenails may be confluent. There is often a positive family history, and the 3rd and 4th toes are involved most commonly. Symptoms are extremely rare, and cosmetic concerns are uncommon. Treatment is only required for patients in whom there is an associated polydactyly (Fig. 666-9). In such cases, the border digit is excised, and the extra skin facilitates coverage of the wound. If the syndactyly does not involve the extra toe, then it can be observed. A complex syndactyly may be seen in patients with Apert syndrome.

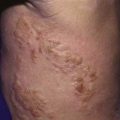

Annular Bands

Bands of amniotic tissue associated with amniotic disruption syndrome (early amniotic rupture sequence, congenital constriction band syndrome, annular band syndrome) can become entwined along the extremities, resulting in a spectrum of problems from in utero amputation (Fig. 666-10) to a constriction ring along a digit (Fig. 666-11) (Chapter 102). These rings, if deep enough, can impair arterial or venous blood flow. Concerns regarding tissue viability are less common, but swelling from impairment in venous return is often a great problem. The treatment of annular bands usually involves observation; however, circumferential release of the band may be required emergently if arterial inflow is obstructed or electively to relieve venous congestion.

Macrodactyly

Macrodactyly represents an enlargement of the toes and can occur as an isolated problem or in association with a variety of other conditions such as Proteus syndrome (Fig. 666-12), neurofibromatosis, tuberous sclerosis, and Klippel-Trenaunay-Weber syndrome. This condition results from a deregulation of growth, and there is hyperplasia of one or more of the underlying tissues (osseous, nervous, lymphatic, vascular, fibrofatty). Macrodactyly of the toes may be seen in isolation (localized gigantism) or with enlargement of the entire foot. In addition to cosmetic concerns, patients might have difficulty wearing standard shoes.

Coughlin MJ. Lesser toe abnormalities. Instr Course Lect. 2003;52:421-444.

Lokiec F, Ezra E, Krasin D, et al. A simple and efficient surgical technique for subungual exostosis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:76-79.

Yang G, Yanchar NL, Lo AY, et al. Treatment of ingrown toenails in the pediatric population. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(5):931-935.

666.11 Painful Foot

Harish S. Hosalkar, David A. Spiegel, and Richard S. Davidson

A differential diagnosis for foot pain in different age ranges is shown in Table 666-3. In addition to the history and physical examination, plain radiographs are most helpful in establishing the diagnosis. Occasionally, more sophisticated imaging modalities are required.