Chapter 7 The Epidemiology of Restless Legs Syndrome

Although a description of symptoms of restless legs syndrome (RLS) first appeared in the clinical literature more than three centuries ago,1 little is known about the disease on a population level. The publication of the so-called minimal criteria of RLS in 19952 and their revision in 20033 have fostered research on the population level, and the number of conducted epidemiological studies or those in defined special populations is increasing considerably. However, there are still no published studies on the incidence of the syndrome. In contrast to the limited epidemiological data, many neurophysiological, pharmacological, and brain-imaging studies have been performed over the past two decades. Even though this research has shed some light on the pathophysiology of the disease and has led to effective treatment, the etiology of RLS remains unclear. Population-based epidemiological research can complement knowledge gained in laboratory settings by providing precise estimates of disease prevalence and incidence, generating and testing etiological hypotheses through the analysis of risk factors, clarifying the roles of genetic markers in association studies of cases and controls sampled from the same source population, and evaluating disease outcomes from a population perspective. As with many other examples, in particular from cardiovascular disease, epidemiological research will help to better understand the etiology of RLS and thus eventually lead to improved treatment options and, equally important, permit the development of preventive strategies.

Assessment of Restless Legs Syndrome in Population Studies

RLS is generally diagnosed from a patient’s report of specific symptoms. The medical history or a diagnostic work-up can help in excluding other conditions or in classifying the syndrome as idiopathic or secondary, but no single diagnostic test can as yet detect the presence or absence of the disease. Thus, RLS is one of the few disorders that can be assessed through specific questions of participants in community-based studies. In 1995, the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group (IRLSSG) agreed on four “minimal diagnostic criteria,”2 paving the way for the development of a standardized questionnaire that can be implemented in epidemiological studies. These 1995 “minimal diagnostic criteria” included the following:

Prior to the publication of the standard diagnostic criteria for RLS in 1995, three studies4–6 were either conducted or initiated using nonstandard definitions of RLS. The question sets used in these studies were not validated. Following the introduction of the standard criteria, several additional population-based studies7–14 were carried out. Two of these studies were conducted in Germany and used a newly developed standardized brief questionnaire with the following questions that were based on the minimal diagnostic criteria just listed:

Only respondents who were answering affirmatively to all three questions were classified as cases. In the first study,15 this questionnaire was validated against a case classification done by study physicians who conducted standardized neurological examinations on all participants. A comparison of the RLS classification based on the three questions with the classification by the examining neurologist yielded a high degree of concordance (κ statistic = 0.67).16 The statistical properties of this short questionnaire were also good, with a sensitivity of 87.5%, a specificity of 95.6%, and a likelihood ratio of 18.9. This set of three questions is the only instrument to date that has been validated against a physician diagnosis in studies of the general population.

The 1995 published criteria were slightly revised during a National Institutes of Health (NIH)-sponsored workshop in May 2002. Based on the validated questionnaire used in the German studies, this workshop also gave recommendations3 for the assessment of RLS in population studies, or more generally in epidemiological research. The workshop participants recommended the following criteria:

Prevalence and Incidence of Restless Legs Syndrome

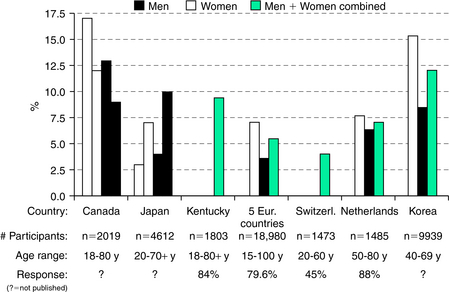

Figure 7-1 shows prevalences in studies4–6,11,17,18 that did not apply the minimal diagnostic criteria but used their own questions or questionnaires, mostly because they were conducted before the minimal criteria were defined and published. As one might expect, there is considerable variation in the reported prevalences. The first two studies, conducted in Canada and Japan, each used two questions to assess RLS, whereas the others only applied a single question. The percentage of positive answers to each used question in the studies is listed in Figure 7-1. These percentages are shown for men and women separately if gender-specific answers were reported in the respective publication. The footnote under each bar clarifies the country in which the study was conducted, giving an acronym of the study (if listed in the publication), reports the number of study participants and their age range, and shows the response rate among those invited to participate if provided in the respective publication; otherwise, a question mark is shown.

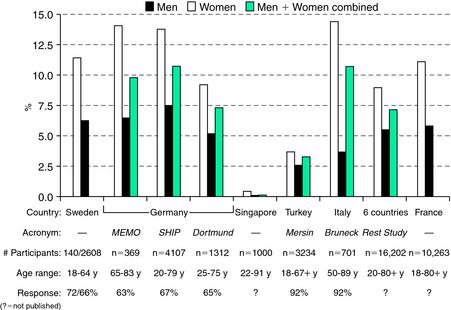

Figure 7-2 summarizes prevalences from population studies7–10,12,14,19 published after the four minimal diagnostic criteria were published in 1995. This figure shows rather consistent gender differences and overall more homogeneous prevalences across all studies. Still, these studies applied different ascertainment methods (questionnaire, personal interview, telephone interview) and study designs (door-to-door survey, random sampling in the general population, random digit dialing). The majority of the latter studies report prevalences of RLS ranging from 6% to 12%. Although the convergence of these findings is reassuring, additional population-based studies are needed, as the studies that used the standard definitions of RLS are of limited size and restricted to certain regions, with most of them in Europe and North America.

The number of studies conducted outside of Europe and North America that assessed the prevalence of RLS in the population is very small. They have, however, received considerable attention because the observed prevalences were very low compared with European populations. The question was raised as to whether RLS is especially rare in Asian populations. Only very few studies related to RLS in Asian general populations are published; one of them reports RLS prevalences in Singapore.19 In this study, the observed RLS prevalence was less than 1%. This finding was often cited as been indicative of a considerably lower prevalence of RLS in Asian populations. However, this conclusion is not warranted by the study, which is strongly affected by selection bias. Thus, the question of whether the RLS prevalence is lower in Asian populations remains to be elucidated by studies that use identical study designs and methods in the assessment of cases. A study from Turkey12 found a 4-week prevalence of RLS of 3.19%. When comparing these prevalences with other European or American populations, the short period of 4 weeks has to be taken into account. Thus, the lifetime or 12-month prevalence that is usually assessed in other studies will be higher in this study from Turkey.

Secondary Forms of Restless Legs Syndrome

A major problem in the assessment of secondary forms of RLS is the lack of a clear definition of what are “secondary forms of RLS.” No consensus exists on the types and severities of comorbid conditions that are predispositions to RLS. The symptoms of so-called secondary RLS are not distinguishable from those of its idiopathic form. Associations with a variety of disorders in single case reports or hospital-based case series have been classified as secondary forms of RLS. Several of these conditions are addressed in later sections of this book, including uremia, iron deficiency anemia, rheumatoid arthritis, diabetes, and amyloid neuropathy. However, the relation between these conditions and RLS in studies of the general population remains largely unclear. To date, only two published studies examined explicitly the influence of potential secondary causes of RLS on a population level.8,13 Both studies found that reduced renal function and anemia had only a small or no contribution to the overall prevalence of RLS, as did diabetes.

Risk Factors

Age

Age is among the factors that cannot be influenced by health-related behaviors or medical treatments. Gender, ethnicity, and genetic susceptibility are other independent factors. Increasing age is an important determinant for the absolute number of affected patients in a given population if a condition is age related. It is well known that many diseases, especially neurological conditions with a dopamine-related pathophysiology, like Parkinson’s disease, are related to age. The number of studies that evaluated age effects for the occurrence of RLS and applied the minimal criteria on a population level is still small.4,5,7,8,11–14 The vast majority of these studies reported an influence of age on the RLS prevalence. These positive age relations were observed independent of the overall RLS prevalence in the studied population, which differed considerably. The magnitude of the association with age in most of these studies is strong. A 2- to 3-fold increase in the prevalence of RLS between young age (20 to 29 years) and older age (11 to 69 years) was found. The highest age groups in these studies usually had the smallest numbers of study participants. Whether increasing age beyond age 70 is associated with a higher prevalence of RLS is uncertain because the numbers of studied individuals in these age groups are small. Therefore, the question of whether the prevalence of RLS further increases in the very old, reaches a plateau, or even decreases remains to be elucidated and can only be answered if this very old group of the population is further examined. Another question related to the RLS prevalence in higher ages is the contribution of the so-called secondary RLS and associated conditions. The associations between RLS and the most important conditions are described in later sections. Because many of these conditions are also related to age, it can be expected that the prevalence of so-called secondary RLS is low in younger age groups and increases with age.

Gender

Many studies have observed higher prevalences of RLS in women than in men.7,8,11,13,14 In particular, studies performed after the minimal criteria had been published in 1995 found that women were approximately twice as often affected with RLS than men. Reasons for the observed gender differences remain largely unexplored. The gender effect was observed at high and low prevalences of RLS in the respective study population. A number of methodological aspects have to be considered in the analysis of gender effects. The assessment of RLS completely relies on self-report of symptoms. It is known that, regardless of the mode of assessment (personal interview or questionnaire), women often perceive symptoms differentially than men. This is especially true for symptoms related to psychological well-being and/or psychiatric symptoms, but it is also known for several somatic symptoms (e.g., in acute heart attacks). In general, women report a specific symptom already at a low severity level, whereas men only consider something to be a “symptom” if it is really severe. These gender roles and perceptions might also affect the frequency assessment of RLS. The observation of increased prevalence during pregnancy forms a basis for pathophysiological considerations about the role of sex hormones in the onset of RLS. In one of the German studies,8 a strong association between the number of children borne by women and the occurrence of RLS was observed.

Other Risk Factors

Several population studies have attempted to evaluate risk factors other than gender associated with RLS. In a U.S. study,5 RLS patients had a higher prevalence of self-reported diabetes and a higher body mass index, exercised less, and consumed less alcohol than did control subjects. Further research, especially about the impact of health-related behaviors such as physical activity, alcohol consumption, smoking, and diet, on the occurrence of RLS is needed because any potential association would be subject to preventive strategies. However, there is no consistency to date in the reports of the few studies that examined the role of health-related behaviors in the occurrence of RLS.

The few findings for the association between iron metabolism and RLS on a population level are controversial. Five parameters of iron metabolism within or below clinical norms were not associated with increased risks of RLS in one study,16 whereas the soluble transferrin receptor was significantly higher in RLS cases compared with control subjects without RLS in another study.13 The relation between iron metabolism and RLS is further described in later sections.

Clinical Significance

Given the high prevalence of RLS in most epidemiological studies, the condition is likely to represent a major cause of morbidity and lost productivity in certain populations. RLS is significantly associated with diminished quality of life.8,14,20 In the study from southern Germany,7 RLS patients had significantly higher depression scores, as measured with the Center of Epidemiologic Studies—Depression Scale (CES-D). The same association with depressed mood and/or social isolation was reported in two Swedish studies.9,10

No consensus exists on the question if disease severity should be included in the classification of RLS cases. Although this is less of a problem in clinical settings, the question clearly arises in population studies where a number of identified cases will have infrequent symptoms with low or only moderate severity. Only few and very recent studies have assessed symptom frequency on a population level. They found that the majority (55% to 69%) of identified cases had symptoms once or more often per week. But it is unclear to what extent symptom frequency is related to symptom severity, especially in those with infrequent symptoms, such as less than once per week. Only one study has assessed symptom severity of RLS in the general population using the IRLSSG Severity Scale.13 It found that two thirds of the identified cases in an elderly general population had moderate to severe symptoms. However, adding this instrument to an interview or questionnaire considerably extends the number of questions, which is often not feasible in large-scale epidemiological studies with several thousands of participants. Thus, further research is necessary to analyze whether symptom frequency can serve as a proxy for symptom severity in studies with a large number of participants.

Perspectives of Epidemiological Research in Restless Legs Syndrome

The definition of the four minimal criteria in 1995 was followed by an increasing number of studies that examined frequencies, risk factors, and consequences of RLS in the general population. However, compared with the number of existing studies conducted in RLS patients, the number of population studies is still small, limited to certain geographical areas, and uses different ascertainment tools. Overall, these studies suggest that RLS is a prevalent disease that affects approximately 6% to 12% of the general population and women twice as often as men. There is a strong need to compare the prevalence of RLS across diverse populations and to identify risk factors that are related to specific age groups, genders, ethnicities, medical histories, or genetic susceptibilities. The 2002 NIH workshop emphasized this need for further epidemiological research in RLS.3 The application of the four minimal criteria after 1995 and the revised criteria from the NIH workshop in 2002 in recent years, however, has also demonstrated existing deficits. The major one is the necessity not only to apply these minimal criteria for the identification of RLS cases in population studies but also to use identical wording in the verbalization of the criteria within one language. Thus, the next step would be to translate this standardized text into different languages using established forward and backward translation procedures that take cultural differences between expressions in different languages into account. The latter might very well be a major contributor to prevalence differences between populations with different cultural backgrounds. Another deficit is the lack of prospective studies to assess the incidence of RLS in the general population. Incident case ascertainment in prospective studies is necessary to overcome methodological problems related to risk factor analyses based on prevalent cases. Despite the availability of effective treatment, as well as a large number of clinical and experimental studies, the etiology of RLS remains unknown. More information about lifestyle, medical, genetic, and biochemical risk factors for RLS is needed to expand treatment options and to generate additional testable hypotheses that will guide future research designed to increase understanding of the origins of this disease. This insight into the etiology of RLS is critical to identify prevention strategies and improve management of this syndrome. Although effective pharmacological treatment is available, newer agents with fewer side effects and/or nonpharmacological therapies would undoubtedly be welcomed by RLS sufferers. Further, preventive strategies among those at higher risk for the development of the disorder might be the most cost-effective intervention for RLS.

1. Willis T. The London Practice of Physick. London: Bassett and Crooke, 1685.

2. Walters AS. Toward a better definition of the restless legs syndrome. The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Mov Disord. 1995;10:634-642.

3. Allen RP, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: Diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the Restless Legs Syndrome Diagnosis and Epidemiology Workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101-119.

4. Lavigne GJ, Montplaisir JY. Restless legs syndrome and sleep bruxism: Prevalence and association among Canadians. Sleep. 1994;17:739-743.

5. Phillips B, Young T, Finn L, et al. Epidemiology of restless legs symptoms in adults. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2137-2141.

6. Kageyama T, Kabuto M, Nitta H, et al. Prevalences of periodic limb movement-like and restless legs-like symptoms among Japanese adults. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;54:296-298.

7. Rothdach AJ, Trenkwalder C, Haberstock J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of RLS in an elderly population—The MEMO Study. Memory and Morbidity in Augsburg Elderly. Neurology. 2000;54:1064-1068.

8. Berger K, Luedemann J, Trenkwalder C, et al. Sex and the risk of restless legs syndrome in the general population. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:196-202.

9. Ulfberg J, Nystrom B, Carter N, et al. Restless legs syndrome among working-aged women. Eur Neurol. 2001;46:17-19.

10. Ulfberg J, Nystrom B, Carter N, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome among men aged 18 to 64 years: An association with somatic disease and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Mov Disord. 2001;16:1159-1163.

11. Ohayon MM, Roth T. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:547-554.

12. Sevim S, Dogu O, Camdeviren H, et al. Unexpectedly low prevalence and unusual characteristics of RLS in Mersin, Turkey. Neurology. 2003;61:1562-1569.

13. Hogl B, Kiechl S, Willeit J, et al. Restless legs syndrome: A community-based study of prevalence, severity, and risk factors. Neurology. 2005;64:1920-1924.

14. Allen RP, Walters AS, Montplaisir J, et al. Restless legs syndrome prevalence and impact: REST general population study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:1286-1292.

15. Rothdach A, Winkelmann J, Trenkwalder C, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome in an elderly general population: The MEMO Study. Neurology. 1999;52:A287-A288.

16. Berger K, von Eckardstein A, Trenkwalder C, et al. Iron metabolism and the risk of restless legs syndrome in an elderly general population—The MEMO Study. J Neurol. 2002;249:1195-1199.

17. Schmitt BE, Gugger M, Augustiny K, et al. Prevalence of sleep disorders in an employed Swiss population: Results of a questionnaire survey. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 2000;130:772-778.

18. Rijsman R, Neven AK, Graffelman W, et al. Epidemiology of restless legs in the Netherlands. Eur J Neurol. 2004;11:607-611.

19. Tan EK, Seah A, See SJ, et al. Restless legs syndrome in an Asian population: A study in Singapore. Mov Disord. 2001;16:577-579.

20. Schredl M. Dream recall frequency and sleep quality of patients with restless legs syndrome. Eur J Neurol. 2001;8:185-189.