193 The Emergency Psychiatric Assessment

• The emergency psychiatric evaluation is a focused medical assessment with the primary goal of distinguishing between acute medical and psychiatric conditions.

• Primary mental disorders include disturbances in thought, mood, or personality. The onset of such disorders generally occurs at younger ages.

• Delirium and dementia are causes of global cognitive impairment that may be mistaken for psychiatric disease in emergency department patients, especially the elderly.

• Approximately 50% of patients seeking emergency psychiatric services have a poorly treated or undiagnosed medical illness contributing to their symptoms.

• Provisional diagnoses should drive the need for and extent of diagnostic testing.

• Acute interventions should improve the patient’s cooperation, reduce agitation, prevent secondary harm, and initiate treatment of the primary mental disorder.

Epidemiology

Cases of psychiatric illness in emergency department (ED) patients have increased 15% in the past decade and now account for 6% of ED visits. Declining inpatient psychiatric beds and limited community mental health resources complicate the care for this population of patients.1

Pediatric ED visits for psychiatric illness are less well studied, although the predominance of cases occur in the adolescent age group. Suicide prevention is the overriding concern. Teen suicide has tripled since 1950 and is the third leading cause of death in adolescents.2

Pathophysiology

Controversy surrounds the “medical clearance” process, more appropriately referred to as the “focused medical assessment.” The evidence available to guide emergency practice remains limited and conflicting. Much of the debate revolves around the differing expectations and priorities of emergency physicians (EPs) and psychiatric consultants. The responsibilities of the EP are to obtain an appropriate history, identify the degree of stress, rule out medical cause, recognize the need for developing specific interventions, arrange psychiatric consultation, and plan disposition.3

Definitions

The fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) distinguishes “mental disorders that are due to a general medical condition” from “primary mental disorders.”4 The terms organic and functional are no longer used to differentiate between illnesses of medical and psychiatric origin (Box 193.1). Clinical practice teaches us that the separation between mental and medical causes is often blurred.

Box 193.1 Medical Causes of Disturbed Behavior versus Primary Mental Disorders

Dementia

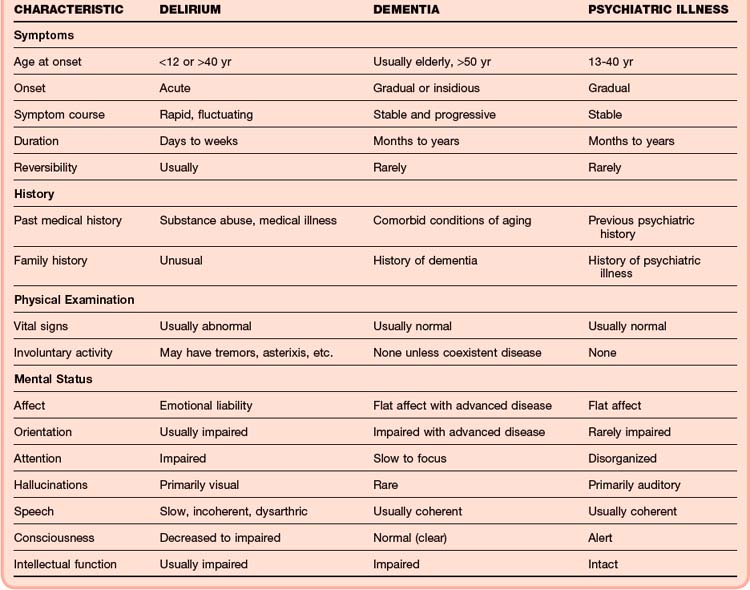

Pervasive disturbance of cognitive function is the hallmark of dementia. Deficits commonly involve memory, judgment, personality, and language. Patients have no clouding of consciousness. The earliest sign of dementia is subtle memory loss, which may promote anxiety, depression, and psychosis. Patients with dementia may experience an acute worsening of symptoms when stressors overwhelm their intellectual and physiologic reserves. As the disease progresses, patients become less capable of recognizing concomitant medical illnesses (Table 193.1).

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The prevalence of coexisting medical illness in psychiatric patients has been reported to be as high as 50%.1 Untreated medical illness often causes deterioration of baseline cognitive function in patients with a known psychiatric disorder. The prevalence of medical disease in patients seen in the ED with an acute exacerbation of an existing mental illness may be as high as 80%.3 Up to 50% of patients demonstrate a causal relationship between acute medical and psychiatric complaints.5 Five groups are regarded to be at high risk for medical illness: older patients, patients with history of substance abuse, patients without a psychiatric diagnosis, patients with preexisting medical disorders, and patients from a lower socioeconomic level.6

The EP must answer six key questions during the focused medical assessment:

1. Is the patient stable or unstable?

2. Is the behavior the result of an underlying medical illness?

3. What is the severity of the primary mental disorder?

4. Is psychiatric consultation necessary?

5. Does the patient need to be detained to facilitate emergency treatment?

6. What capability does the psychiatric facility have to treat medical conditions?

History

A focused history of the present illness that reviews current symptoms, elicits precipitating circumstances, assesses risk severity, and establishes a time course should be obtained. Critical historical elements include past medical and psychiatric illnesses, medication use (Table 193.2), substance abuse or addiction, and a family history of psychiatric illnesses.

| DRUG CLASS | REACTIONS |

|---|---|

| Amphetamines |

HMG-CoA, 3-Hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A.

Modified from Drugs that may cause psychiatric symptoms. Med Lett Drugs Ther 2002;44:59-62.

For children and teens, the history should concentrate on the precipitant of the mental health crisis. Particular areas to review include school performance, relationship with family and peers, living situation, family composition, sexuality, and neighborhood environment. When developmentally appropriate, the history should be obtained from both the child and the caretaker. Up to 20% of adolescents have a serious behavioral or medical problem.2

Physical Examination

An organized and thorough physical examination should be performed. Cursory examination of psychiatric patients is unacceptable. Uncooperative or fully dressed patients may hide weapons, illicit drugs, evidence of physical abuse, or signs of medical illness. Younger patients are more likely to receive a cursory examination.7

The patient’s vital signs should be scrutinized for evidence of shock, metabolic derangement, or infection. Search for signs of impaired organ and tissue perfusion. Check for hypoxia and abnormal respiratory effort. Look for abrasions or contusions that may represent recent trauma or unsuspected head injury. Identify subtle, focal weakness or neglect suggestive of possible neurologic impairment. Evaluate for other signs of neurologic disease, including dysesthesia (distortion of sense), apraxia (loss of the ability to carry out purposeful movements), agnosia (inability to recognize sensory stimuli), left-right disorientation, aphasia, or an inability to follow commands. Sensory illusions can be associated with neurologic conditions or intoxications. Visual, tactile, and olfactory hallucinations are generally attributable to medical disease (Table 193.3).

Table 193.3 Physical Examination Findings and Medical Causes of Abnormal Behavior

| ORGAN SYSTEM | FINDING | POTENTIAL MEDICAL CONDITION |

|---|---|---|

| General | Hyperthermia | Thyrotoxicosis, vasculitis, alcohol withdrawal, sedative-hypnotic withdrawal, meningitis, inflammatory processes |

| Hypothermia | Sepsis, dermal disease, endocrine disorders, CNS dysfunction, intoxication | |

| Hypotension | Shock, Addison disease, hypothyroidism, adverse drug reactions, dehydration | |

| Hypertension | Hypertensive encephalopathy, stimulant abuse, anticholinergic excess | |

| Abdomen | Distention | Constipation, hepatic encephalopathy with ascites, obstruction, perforation of a viscus with sepsis |

| Masses | Liver disease, cancer, obstruction | |

| Cardiovascular | Bradycardia | Hypothyroidism, Stokes-Adams syndrome, elevated intracranial pressure |

| Tachycardia | Hyperthyroidism, infection, heart failure, pulmonary embolism, alcohol intoxication or withdrawal | |

| Arrhythmias | Toxins, embolic strokes, electrolyte abnormalities | |

| Neurologic | Confusion | Hypoxia, infection, toxins, electrolyte abnormalities, trauma, meningitis, encephalitis |

| Seizures | Infections, head trauma, intoxication, poisonings, primary seizure disorder, meningitis | |

| Motor deficits | Stroke, encephalopathy, neuropathy, spinal trauma, movement disorders | |

| Aphasia | Stroke, head trauma, CNS disease | |

| Headache | Head trauma, meningitis, vasculitis, stroke, toxins, hypertensive emergencies | |

| Visual deficits | Head trauma, increased intracranial pressure, meningitis, cerebritis, ocular trauma, poisoning | |

| Pulmonary | Tachypnea | Metabolic acidosis, pulmonary embolism, pneumonia, cardiac failure, fever |

| Wheezing, stridor | Reactive airway disease, airway foreign body, hypoxia | |

| Rales | Pneumonia, pulmonary effusions, heart failure | |

| Skin | Abrasions and contusion | Closed head injury, intracranial hemorrhage |

CNS, Central nervous system.

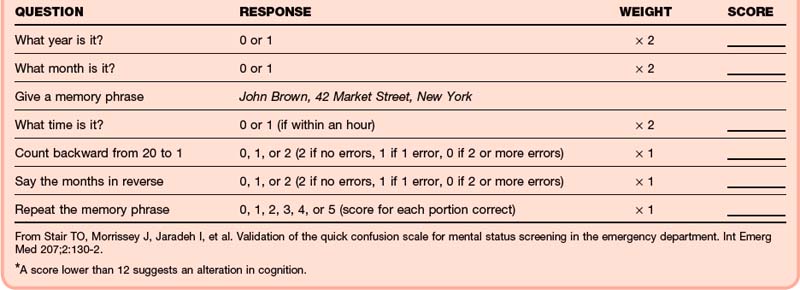

The mental status examination is critical and should assess the patient’s level of consciousness, appearance, behavior, mood, affect, language, thought form and content, perceptions, and cognition. Much of this information can be obtained indirectly by observing the patient during the interview. Standardized assessment tools such as the Folstein Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMS) or the Quick Confusion Scale (QCS) allow detection of subtle deficits (Tables 193.4 and 193.5). Given the demands of a busy ED, many EPs find administering a formal MMS impractical—abbreviated tools are often preferred. Scores of less than 12 on the shorter QCS six-question battery have been shown to correlate with impaired cognition.8

Table 193.4 Mini-Mental Status Examination

| CATEGORY | TEST BEHAVIOR | SCORE |

|---|---|---|

| Orientation | What is the (year) (season) (date) (day) (month)? | 5 |

| Where are we (state) (country) (town) (hospital) (floor)? | 5 | |

| Registration | Name 3 objects (1 second to say each). Ask the patient to name all 3 after you have said them. Give 1 point for each correct answer. Repeat until all 3 have been learned. Count and record trials __________. | 3 |

| Attention and calculation | Serial 7s, backward from 100. 1 point for each correct answer. Stop after 5 answers. Alternatively, spell “world” backward. | 5 |

| Recall | Ask for the 3 objects named above. Give 1 point for each correct answer. | 3 |

| Language | Name a pencil and watch. | 2 |

| Repeat the following “No ifs, ands, or buts.” | 1 | |

| Follow a 3-stage command (e.g., “Take this paper in your hand, fold it in half, and put it on the floor.”) | 3 | |

| Read and obey the following: CLOSE YOUR EYES. | 1 | |

| Write a sentence. | 1 | |

| Copy the design shown (two intersecting pentagrams). | 1 |

Maximum score = 30. A score of less than 23 indicates cognitive impairment.

From Folstein M. “Mini-Mental State” a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189-98.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

Patients with disturbed behavior or thought processes should be presumed to have a medical origin of their condition. Patients with chronic illnesses such as thyroid disease, diabetes mellitus, reactive airway disease, heart failure, stroke, and dementia may have a sudden and dramatic impairment in cognition or affect. Life-threatening causes of delirium should be considered in all patients with psychiatric disturbances. Primary mental disorders should be diagnosed only after serious medical conditions have been convincingly excluded (Box 193.2).

Diagnostic criteria such as those provided in the DSM-IV aid in establishing a provisional psychiatric diagnosis in the ED. Although standardized criteria are useful, interrater agreement among emergency psychiatrists is variable.9

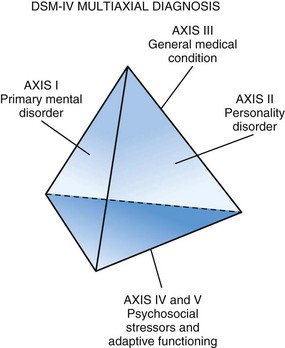

Multiaxial diagnoses serve to organize complex clinical information and acknowledge the interplay of medical and psychiatric disease. Axis I diagnoses reflect mental disorders, axis II diagnoses identify personality disorders, axis III diagnoses include general medical conditions, and axis IV and V diagnoses include psychosocial stressors and adaptive functioning (Fig. 193.1). When evaluating children and teens, complaints should be considered within the context of their physical and social developmental stage.

Diagnostic Testing

No standardized or widely accepted ED protocol exists for performing a focused medical assessment of psychiatric patients.10 Differentiation between medical and psychiatric disease is best accomplished by a detailed history and physical examination. However, it should be noted that many psychiatric facilities have limited medical diagnostic capabilities and that the ED assessment may be the only medical evaluation and source of laboratory testing or imaging that the patient receives.11

Screening tests commonly ordered as part of the emergency psychiatric evaluation include pulse oximetry, complete blood count, chemistry panel with glucose, electrocardiogram, urine toxicology screen, urine pregnancy testing, and serum alcohol level. Testing of liver and thyroid function, as well as computed tomography imaging of the brain, should be based on the history (or previous diagnosis) and findings on physical examination. Chest radiography, lumbar puncture, arterial blood sampling, and electroencephalography are rarely indicated as screening tests in the evaluation of patients with suspected psychiatric illness.12,13

The 2006 American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) clinical policy “Critical issues in the diagnosis and management of the adult psychiatric patient in the emergency department” posed three questions related to diagnostic testing14:

1. What testing is necessary to determine medical stability in alert, cooperative patients with normal vital signs, a noncontributory history and physical examination, and psychiatric symptoms?

2. Do the results of a urine drug screen for drugs of abuse affect management in alert, cooperative patients with normal vital signs, a noncontributory history and physical examination, and a psychiatric complaint?

3. Does an elevated alcohol level preclude the initiation of a psychiatric evaluation in alert, cooperative patients with normal vital signs and a noncontributory history and physical examination?

EPs are frequently asked to perform detailed screening laboratory and radiographic testing to exclude any medical illness that may be causing or contributing to the patient’s psychiatric symptoms. Early studies of the coexistence of medical illness in patients with psychiatric symptoms argued for the routine use of laboratory testing, although they did not specify which components of the history and physical examination were included or performed on all patients.14 These studies involved patients admitted directly to mental health facilities without a medical screening examination. When routine testing is performed, abnormal results are often clinically insignificant.13,15–17 Patients who are delirious, have abnormal vital signs, or display altered cognitive states mandate more extensive evaluations. The 2006 ACEP consensus panel noted that routine laboratory testing is of limited utility in teens and younger adults. The value of routine laboratory testing in younger children with psychiatric symptoms has not been studied in ED populations.2

EPs and emergency psychiatrists often disagree on the necessity for a urine toxicology screen as part of emergency focused medical assessment. Although many surveyed EPs find a urine drug screen to be unnecessary, psychiatrists may use the test to determine a cause of the patient’s symptoms or aid in disposition and long-term care of a patient.13,18 Retrospective studies suggest that the sensitivity of routine toxicologic testing for the diagnosis of a medical cause of isolated psychiatric complaints is just 20%.19 Schiller et al. prospectively tested approximately 400 patients and found no difference in terms of inpatient or outpatient disposition or hospital length of stay.17 The ACEP recommends against routine testing for drugs of abuse in alert, awake, cooperative patients. They acknowledged that receiving psychiatric facilities often require such testing but urged that testing not delay psychiatric assessment or admission or transfer.

Diagnostic testing of psychiatric patients in the ED should accomplish one of the following goals: (1) detect or exclude the presence of a condition that has treatment consequences, (2) determine the relative safety or appropriate dose of potential alternative treatments, or (3) provide baseline information useful for monitoring response to treatment. ED protocols should be based on local disease prevalence, common clinical findings, the potential for needed treatment, and the likelihood of admission or extended monitoring. In some states, emergency medicine and psychiatry organizations have created consensus guidelines regarding ED medical assessment of psychiatric patients in an effort to reduce unnecessary resource utilization.3

A few studies have suggested that it may be possible to identify patients with psychiatric complaints who can safely bypass the traditional ED focused medical assessment and be directed for primary psychiatric evaluation.20,21 These studies suggest that patients must be alert with normal vital signs, not be under the influence of drugs or alcohol, and have a history of psychiatric illness that is consistent with their current symptoms. The availability of immediate online medical control is critical.

Treatment

Patient and staff safety is of paramount importance. Suicidal patients need to be monitored closely and protected from self-harm. Agitated patients constitute a threat to themselves and to others. Rapid administration of psychotropic or anxiolytic medications (or both) is a safe and effective method for controlling potentially dangerous patients. Seclusion, sitters, and the use of physical restraints may be required temporarily. Chapters 194 to 197 provide specific treatment recommendations for psychotic, violent, and suicidal patients. Disease-appropriate treatments of the various causes of delirium and dementia are reviewed elsewhere in this text.

Follow-Up and Next Steps in Care

The emergency psychiatric focused medical assessment should result in one of four outcomes: (1) a medical cause of the chief complaint is identified, (2) a primary mental disorder is suspected, (3) the symptom or condition is self-limited and resolves, or (4) the cause of the abnormal behavior or disordered thought process remains unclear and mandates further evaluation (medical admission) (Box 193.3).

Box 193.3 Potential Outcomes of the Emergency Psychiatric Evaluation

A medical cause of the abnormal behavior or thought process is identified and treatment is initiated.

A primary mental disorder is suspected and psychiatric consultation is obtained.

The patient’s condition is self-limited and has resolved. Discharge criteria are met.

The cause of the abnormal behavior or disordered thought process remains unclear. Further evaluation mandates admission to a medical service with psychiatric consultation.

If subacute medical conditions are identified in patients requiring psychiatric admission, the accepting psychiatric service must be capable of providing appropriate care and follow-up. Untreated medical illnesses may complicate psychiatric interventions and result in repeated visits to the ED (Table 193.6).

Table 193.6 Common Pitfalls in the Emergency Psychiatric Evaluation

| PITFALL | INCORRECT RATIONALE | RESULTANT ERROR |

|---|---|---|

| Inappropriate or premature referral to psychiatry | Bizarre, disruptive behavior is less urgent or serious than the medical complaints of other ED patients. Initial decisions are often based on a single symptom or historical feature. |

Provider bias and faulty assumptions lead to incorrect diagnoses. |

| Bizarre behavior or thoughts are “diagnostic” of primary mental disorders | Delusions, hallucinations, and disorganized thoughts are usually signs of primary psychosis. | These symptoms are nonspecific and may reflect delirium. |

| Premature referral of violent patients to psychiatry | Violent patients place staff and others at risk and disrupt the flow of care in the emergency department. | Violent behavior may be the result of an underlying medical illness. |

| Allowing biased staff to hinder evaluation and guide care | Certain patients (alcoholics, drug abusers, suicidal individuals) create their own disease and do not deserve urgent intervention. | Blaming patients for their illness does not correct the behavior or address the underlying psychiatric disease. |

| Provider convinced that the patient is insincere | The provider does not believe the threats or complaints of seemingly unreliable patients. | The potential for serious or lethal outcomes may be underestimated. |

| Discharging elderly patients with “dementia” | Dementia cannot be treated. | The provider presumes that all elderly patients are permanently impaired (60% of dementias are treatable). |

Baren JM, Mace SE, Hendry PL, et al. Children’s mental health emergencies—part 2. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24:485–498.

Lukens TW, Wolf SJ, Edlow JA, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the diagnosis and management of the adult psychiatric patient in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:79–99.

Szpakowicz M, Herd A. “Medically cleared”: how well are patients with psychiatric presentations examined by emergency physicians? J Emerg Med. 2008;35:369–372.

Zun LS. Evidence-based evaluation of psychiatric patients. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:35–39.

1 Sood TR, McStay CM. Evaluation of the psychiatric patient. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2009;27:669–683.

2 Baren JM, Mace SE, Hendry PL, et al. Children’s mental health emergencies—part 2. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2008;24:485–498.

3 Zun LS. Evidence-based evaluation of psychiatric patients. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:35–39.

4 First MB, Frances A, Pincus HA. DSM-IV-TR handbook of differential diagnosis. Arlington, Va: American Psychiatric Association, 2002.

5 Koran LM, Sox HC, Marton KI, et al. Medical evaluation of psychiatric patients. I. Results in a state mental health system. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:733–740.

6 Janiak BD, Atteberry S. Medical clearance of the psychiatric patient in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2010. Feb 1, online http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.10.026

7 Szpakowicz M, Herd A. “Medically cleared”: how well are patients with psychiatric presentations examined by emergency physicians? J Emerg Med. 2008;35:369–372.

8 Williams ER, Shepherd SM. Medical clearance of psychiatric patients. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2000;18:185–198.

9 Way BB, Allen MH, Mumpower JL, et al. Interrater agreement among psychiatrists in psychiatric emergency assessments. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:1423–1428.

10 Korn CS, Currier GW, Henderson SO. “Medical clearance” of psychiatric patients without medical complaints in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2000;18:173–176.

11 Kanich W, Brady WJ, Huff JS, et al. Altered mental status: evaluation and the etiology in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20:613–617.

12 Zun LS, Hernandez R, Thompson R, et al. Comparison of EPs’ and psychiatrists’ laboratory assessment of psychiatric patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22:175–180.

13 Amin M, Wang J. Routine laboratory testing to evaluate for medical illness in psychiatric patients in the emergency department is largely unrevealing. West J Emerg Med. 2009;10:97–100.

14 Lukens TW, Wolf SJ, Edlow JA, et al. Clinical policy: critical issues in the diagnosis and management of the adult psychiatric patient in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:79–99.

15 Tenenbein M. Do you really need that emergency drug screen. Clin Toxicol. 2009;47:286–291.

16 Fortu JM, Kim IK, Cooper A, et al. Psychiatric patients in the pediatric emergency department undergoing routine urine toxicology screens for medical clearance. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2009;25:387–392.

17 Shiller MJ, Shumway M, Batki SL. Utility of routine drug screening in a psychiatric emergency setting. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:474–478.

18 Baraff LJ, Janowicz N, Asarnow JR. Survey of California emergency departments about practices for management of suicidal patients and resources available for their care. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;48:452–458.

19 Olshaker JS, Browne B, Jerrard DA, et al. Medical clearance and screening of psychiatric patients in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1997;4:124–128.

20 Shah SJ, Fiorito M, McNamara RM. A screening tool to medically clear psychiatric patients in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2010. Mar 29, online http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2010.02.017

21 Cheney P, Haddock T, Sanchez L, et al. Safety and compliance with an emergency medical service direct psychiatric center transport protocol. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:750–756.