The Elder Patient

Perspective

The population of the United States is aging, with the proportion of people older than 65 years increasing at twice the rate of younger people. In 2010, 13% of the population was older than 65 years, and by 2045 one in five people are expected to be older than that age.1 In 2008 the first baby boomer turned 62 years old, and as of January 2011 this so-called silver tsunami began to qualify for Medicare.

These changing demographics affect the practice of emergency medicine. In 2008 elders accounted for 46% of the 123 million emergency department (ED) visits, and ED visits in this age group are increasing by one third every 10 years.2 Elders presenting to the ED are more likely to arrive by ambulance, to have a more emergent condition than younger patients, and to require longer evaluations.3 One third of these patients are admitted, many to the intensive care unit.4 As the number of ED visits by elders continues to climb, the health care impact will be enormous.

Principles of Disease

Physiologic changes of aging affect virtually every organ system and have many effects on the health and functional status of elders (Table 182-1). Heart disease is the leading cause of hospitalization and death.5 Increased peripheral vascular resistance with aging leads to an increased risk of hypertension. Decreased inotropic and chronotropic cardiac functioning compromises the patient’s ability to respond to physiologic stressors. Atherosclerosis is common and contributes not only to the rate of heart disease but also to the risk of vascular conditions (e.g., stroke, mesenteric ischemia, peripheral vascular disease, aortic dissection, and abdominal aortic aneurysm).

Table 182-1

Physiologic Changes of Aging and Potential Effects

| PHYSIOLOGIC CHANGE | POTENTIAL EFFECT |

| Nervous System | |

| Decreased efficiency of blood-brain barrier | Increased risk of meningitis |

| Potential for exaggerated medication responses | |

| Decreased response to changes in temperature | Impaired thermoregulation |

| Alteration of autonomic system function | Variations in blood pressure; risk of orthostatic hypotension |

| Reduced erectile function | |

| Urinary incontinence | |

| Alterations in neurotransmitters | Slowing of complex mental functioning |

| Skin and Mucosa | |

| Atrophy of all skin layers | Decreased insulation |

| Increased risk of skin injury | |

| Increased risk of infection | |

| Sweat glands decreased in number or activity | Potential for hyperthermia |

| Musculoskeletal System | |

| Progressive bone loss | Increased risk of fractures |

| Atrophy of fibrocartilaginous and synovial tissues | Joint instability and pain |

| Impaired balance and mobility | |

| Decrease in lean body mass | Alteration in pharmacokinetics |

| Increase in proportion of adipose tissue | Alteration in pharmacokinetics |

| Immune System | |

| Decrease in cell-mediated immunity | Increased susceptibility to neoplasms |

| Tendency to reactivate latent diseases | |

| Decreased antibody titers | Increased risk of infection |

| Cardiovascular System | |

| Decreased inotropic response | Less efficient response to myocardial wall stress |

| Decreased chronotropic response | Decreased maximal heart rate |

| Increased peripheral vascular resistance | Increased blood pressure |

| Decreased ventricular filling | Changes in organ perfusion |

| Pulmonary System | |

| Decreased vital capacity | |

| Decreased lung and airway compliance | Increased airway resistance |

| Decreased chemoreceptor response to hypercapnia or hypoxemia | Potential for rapid decompensation |

| Decreased ventilatory drive | Decreased PaO2 and increased PaCO2 |

| Decreased diffusion capacity | Decreased PaO2 |

| Hepatic Function | |

| Decrease in hepatic cell mass | Reduced ability to regenerate |

| Decrease in hepatic blood flow | Alteration in pharmacokinetics |

| Alterations in microsomal enzyme activity | Alteration in pharmacokinetics |

| Renal System | |

| Decrease in renal cell mass | Decreased drug elimination |

| Thickening of basement membrane | Decreased drug elimination |

| Reduced hydroxylation of vitamin D | Risk of hypocalcemia, osteoporosis |

| Decrease in total body water | Alteration in pharmacokinetics |

| Decreased thirst response | Risk of dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities |

| Decreased renal vasopressin response | Risk of dehydration and electrolyte abnormalities |

| Gastrointestinal System | |

| Decrease in gastric mucosa | Increased risk of gastric ulcer |

| Decrease in bicarbonate secretion | Increased risk of gastric ulcer |

| Decrease in blood flow to gastrointestinal system | Increased risk of perforation |

| Decreased epithelial cell regeneration | Longer healing times |

Because of several changes that occur with aging, elders are at higher risk for infections. Prostate disease in men and incomplete bladder emptying in women with pelvic floor abnormalities predispose to urinary tract infections. Microaspiration increases the risk of pneumonia, and fragile, aging skin prone to injury and breakdown increases the risk of infections of the skin and soft tissues. Immunosenescence of cell-mediated immunity predisposes patients to reactivation of latent diseases (e.g., tuberculosis) and may be associated with increased susceptibility to neoplasms. Cancer is the second most common cause of hospitalization and death in older patients.5

Fractures are the fifth leading cause of hospitalization, reflecting the high rate of osteoporosis, particularly in women.4 Arthritis is the most prevalent outpatient disease in elders because of the wear on cartilaginous joints, particularly of the knees, hips, and hands.4 Arthritis greatly affects quality of life, and these patients report fair or poor health approximately three times more often than patients without arthritis do.

Pharmacologic Considerations

Polypharmacy, drug interactions, and misuse and abuse of medications in elders are crucial health care issues. Elders currently consume more than 30% of the prescription drugs in the United States, and this figure is projected to increase to 50% by 2020. More than 40% of elders use five or more drugs weekly, and more than 10% use ten or more.6,7

Although multiple medications may be necessary to treat the medical problems that occur with aging, significant adverse health effects may result. Underlying medical problems, multiple physicians, changing pharmacokinetics of aging, and treatment of side effects of one medication with another drug are all contributory. Twelve percent to 30% of admitted elders have adverse drug reactions or interactions as a primary or major contributing factor to their admission, and 25% of these drug reactions or interactions are serious or life-threatening.6,7

Several medications frequently used in the outpatient elder population are considered to be “potentially inappropriate medications.” This list includes but is not limited to narcotic analgesics, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, sedative-hypnotics, muscle relaxants, and antihistamines.8–10 These agents are generally not recommended for use in this population of patients and should be used sparingly.

The medications most often implicated in adverse reactions in elders in the ambulatory setting are cardiovascular medications, followed by diuretics, nonopioid analgesics, hypoglycemics, and anticoagulants.11,12 Caution should be used in prescribing any of these classes as they can contribute to morbidity and mortality in this age group.

The various analgesic medications used in the elderly can cause a wide range of adverse reactions and interactions. Narcotics and sedative-hypnotic agents can decrease cognition and increase the risk of falls and accidents. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may have serious and potentially lethal side effects. The toxicity of NSAIDs includes azotemia, worsened hypertension, and congestive heart failure as a result of sodium retention. Gastrointestinal toxicity ranges from bleeding to perforation.13 The data support use of extreme caution in prescribing NSAIDs. These complications can be seen in patients taking widely available over-the-counter formulations of these drugs. The significant increase in cardiovascular risk with the use of cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitors has led to a dramatic decrease in the use of these agents.

Because of these concerns, pain management in the elderly can pose a challenge. Although a “first, do no harm” philosophy is laudable, treatment of pain is one of the most important remedies physicians have to offer. Three major considerations influence the choice of medication for elderly patients. First, chronic pain (e.g., arthritis pain) may require treatment different from that of an acute painful condition (e.g., wrist fracture). Second, the patient’s underlying medical problems, social situation, and baseline functional status need to be considered.14 Third, starting with low doses, then titrating upward to effect, is the safest strategy.

Psychosocial Issues

The possibility of drug dependence and ethanol abuse should be considered in the treatment of elders. These patients often present with mental status or gastrointestinal complaints or after falls or other trauma. Ethanol dependence is a factor in elders who present in the ED, and dependence on prescription drugs, particularly sedative-hypnotics, is also more prevalent than suspected.15,16 The routine outpatient use of sedative-hypnotics should be avoided and duration limited; dependence on these drugs may cause decreased cognition, and withdrawal from these agents can be life-threatening.

Psychiatric disease in elders often is manifested in atypical fashion. Depression, a common problem, may be manifested as agitation, anxiety, and somatic complaints in addition to the typical depressive symptoms.17,18 Depression often follows chronic illness, loss of physical mobility, diminished cognitive function, bereavement from the death of a spouse or long-time friend, and financial pressures, all of which are common features of old age. Social isolation and loss of independence produce a sense of helplessness and hopelessness that may result in suicidal ideation or action. Certain types of depression, such as “late-life delusional depression” and involutional depression, occur exclusively in old age. In addition, depression may be caused by medication side effects or reversible physiologic conditions (e.g., thyroid disease and malnutrition). Elders often respond to pharmacologic treatment of depression but are prone to the development of adverse effects from antidepressants; selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors seem to be safer. A phenomenon known as sundown syndrome occurs in elderly demented patients, who become highly agitated and disoriented after dark when visual sensory input is diminished and the environment becomes unfamiliar.

Evaluation and Clinical Features

Physical Examination

Of elders with a serious infection, 30% present with a blunted or absent fever response.19 The temperature measurement should be accurate. As an oral temperature may be spuriously low, a rectal temperature should be measured when the presence of fever is uncertain in a patient with a possible infection. When fever is present, elders are much more likely to have a serious (nonviral) infection than are younger patients.20 Of febrile elders presenting to an ED, 89% have an infectious disease.20 Approximately one third are respiratory tract infections, one fifth are urinary tract infections, and nearly one fifth are bacteremia or sepsis.20 Fever in an elder should be taken seriously, with appropriate ancillary testing and a low threshold for admission. Also, a lack of fever does not exclude infection.

Specific Disorders

The incidence of atypical presentation of acute myocardial infarction (AMI) increases with age.21–23 In patients older than 85 years, atypical presentation of myocardial infarction may be anticipated, and a lack of chest pain may be the rule. Only 2 to 6% of elders with AMI, however, have an asymptomatic presentation.21 A painless myocardial infarction is more common with increasing age and occurs more often in women than in men.21–23 Sudden onset of dyspnea may be the only presenting complaint in elders with myocardial infarction. Other presenting complaints include syncope, influenza-like symptoms, nausea, vomiting, confusion, and generalized weakness.22,23 As the prognosis for AMI in elders who present atypically is the same as that for elders who present typically, these atypical presentations are not more benign.

Infections

Evaluation of infections may be difficult because up to nearly half of elders with proven bacterial infections do not have a fever at presentation.24 In addition, the sensitivity of an elevated white blood cell count and bandemia is poor, approximately 44% and 32%, respectively.24

Several infections, particularly pneumonia, urinary tract infections, and sepsis, occur more often in elders. Pneumonia is one of the ten leading causes of hospitalization and death.5 The elderly are more prone because of decreased vital capacity, decreased lung and airway compliance, less ventilatory drive, and poor ciliary function. Combined with decreased cough response and increased esophageal reflux with microaspiration, pneumonia is the leading cause of hospitalization due to infection in elders. Pneumococcus is still a common cause, but gram-negative organisms are also common, as are mixed infections. Reactivation of tuberculosis also should be considered in this age group.

Urinary tract infections are common in elders. The incidence of bacteriuria is 20% in men older than 70 years and 20% in women 65 to 70 years of age, increasing to 23% and 50%, respectively, in men and women older than 80 years.25 Laxity of the pelvic floor and urinary incontinence are significant risk factors in women, whereas prostate enlargement is a significant risk factor in men. The incidence of urinary tract infections increases dramatically in patients with chronic indwelling catheters.

Abdominal Pain

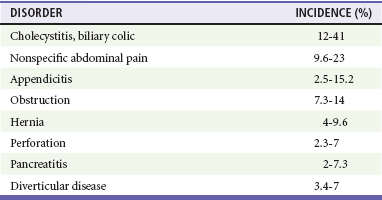

The differential diagnosis (Table 182-2) of abdominal pain in the elderly differs significantly from that in younger patients, particularly in regard to the number of serious and potentially life- threatening causes. The pathologic condition in more than 60% is surgical in nature, a rate nearly double that of younger patients. There is a tenfold higher risk of mortality compared with younger patients.26

Because of the physiologic changes of aging, even life-threatening causes of abdominal pain may be manifested with few or no alarming findings. Elders may complain of vague abdominal pain despite the occurrence of a catastrophic process. The complication rates of typically benign processes in younger patients are dramatically higher in older patients. With aging, the abdominal musculature decreases, and patients are less able to manifest guarding and rebound. In addition, the omentum shrinks and is less able to contain intra-abdominal processes. Atherosclerotic disease, with its resultant decrease in blood flow, causes increased perforation rates in diseases such as cholecystitis and appendicitis. This increased rate of vascular disease also contributes to higher rates of vascular causes of abdominal pain, such as mesenteric ischemia and leaking or ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms.27 The high prevalence of gallstones in elders leads to an increased risk of cholecystitis.

Because of the vague presentation and high rate of serious disease, evaluation of an elderly patient with abdominal pain often requires an extensive battery of laboratory and radiographic tests.28 Elders with potentially catastrophic intra-abdominal processes may not present with a fever or an elevated white blood cell count.26 As a result, ancillary diagnostic ultrasonography, computed tomography, radionuclide studies, and, occasionally, angiography may be vital. Because many elders with abdominal pain have a serious disease, consider admission and close observation when symptoms persist and the diagnosis remains unclear. If the patient is not admitted, a period of ED observation or re-evaluation within 12 hours is prudent.

Major Trauma

Major trauma in elders (see Chapter 39) is relatively uncommon, constituting 8 to 15% of cases in major trauma databases. Elder trauma patients, however, experience higher mortality and poorer functional recovery for a given trauma score.29–32 For virtually any trauma in elderly patients, the circumstances leading to the injury need to be determined and the circumstances questioned. Trauma in the elderly may be due to potentially serious or life-threatening medical causes, such as syncope, hypovolemia due to dehydration or bleeding, cardiac or cerebrovascular disease, or medications.29 Motor vehicle crashes, particularly involving a single vehicle, may result from transient loss of consciousness due to dysrhythmias, syncope, medication side effects, transient ischemic attacks, strokes, or myocardial infarctions.31 These serious medical problems require simultaneous diagnosis and treatment in the setting of trauma and may be as important as or more important than the traumatic injuries.

Preventive Care

Pneumonia, influenza, accidents, and adverse medical events are among the top seven causes of death in elders.5 These conditions account for 15% of admissions and are potentially preventable. Annually, 36,000 adults die of complications from influenza and pneumococcal infections, and most of these deaths occur in elders. Immunization would reduce the incidence of clinical and serologic influenza by half in this population of patients. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has a goal of an 80% immunization rate for patients in high-risk groups, including elders. The actual vaccination rate falls significantly below this goal. In patients 65 years old, 66% and 62% were vaccinated for influenza and pneumococcal disease, respectively, with the lowest rates among multiracial ethnic groups and people of lower socioeconomic means.33 As a result, the CDC recommends that potential vaccination sites be extended to include walk-in clinics and EDs. Elders who have not been hospitalized or have not seen their primary care physician in the previous 3 years average at least one visit to an ED, and many are willing to be vaccinated there.

Falls

In combination with vaccinations, education about accident prevention in the home could have a considerable impact on the overall morbidity and mortality in elders. Falls and adverse medical events are the seventh leading cause of death in elders.5 Whereas a primary care or social service provider may be a more appropriate source of information on fall prevention, the ED may be an additional resource to provide educational services to elders on a case-by-case basis, particularly in reference to any specific incident that prompted the need for emergency care. The leading cause of falls in elders is related to the use of pharmacologic agents, often prescription drugs.30 Reviewing the patient’s medications, searching for agents that might cause decreased cognition or dehydration, and addressing the need for these agents with the patient and the primary care provider could significantly decrease the risk for falls. In addition, informing the patient’s primary care provider that the patient has fallen may facilitate education by the primary physician.

References

1. U.S. Census Bureau. Age and Sex Composition: 2010. http://2010.census.gov/news/releases/operations/cb11-cn147.html.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Health Interview Survey. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db38_tables.pdf.

3. Aminzadeh, F, Dalziel, WB. Older adults in the emergency department: A systematic review of patterns of use, adverse outcomes, and effectiveness of interventions. Ann Emerg Med. 2002;39:238.

4. National Hospital Ambulatory Care Survey. 2008 Emergency department summary tables. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/nhamcs_emergency/nhamcsed2008.pdf.

5. Heron, M, Deaths: Leading causes for 2006. Nat Vital Stat Rep 2010;58:1. www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr58/nvsr58_14.pdf.

6. Budnitz, DS, et al. Medication use leading to emergency department visits for adverse drug event in older adults. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:755.

7. Caterino, JM, Emond, JA, Camargo, CAJr. Inappropriate medication administration to the acutely ill elderly: A nationwide emergency department study, 1992-2000. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1847.

8. McDonnell, PJ, Jacobs, MR. Hospital admissions resulting from preventable adverse drug reactions. Ann Pharmacother. 2002;36:1331.

9. Chin, MH, et al. Appropriateness of medication selection for older persons in an urban academic emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 1999;6:1232.

10. Gaddis, GM, Holt, TR, Woods, M. Drug interactions in at-risk emergency department patients. Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9:1162.

11. Gurwitz, JH, et al. Incidence and preventability of adverse drug events among older persons in the ambulatory setting. JAMA. 2003;239:1107.

12. Hustey, FM, Wallis, N, Miller, J. Inappropriate prescribing in an older ED population. Am J Emerg Med. 2007;25:804.

13. Buffum, M, Buffum, C. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in the elderly. Pain Manag Nurs. 2000;1:40.

14. Culberson, JW, Ziska, M. Prescription drug misuse/abuse in the elderly. Geriatrics. 2008;63:22.

15. Onen, SH, et al. Alcohol abuse and dependence in elderly emergency department patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2005;41:191.

16. Blazer, DB, Wu, LT. The epidemiology of substance use and disorders among middle aged and elderly community adults: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;17:237.

17. Piechniczek-Buczek, J. Psychiatric emergencies in the elderly population. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2006;24:467.

18. Borja, B, Borja, CS, Gade, S. Psychiatric emergencies in the geriatric population. Clin Geriatr Med. 2007;23:391.

19. Norman, DC. Fever in the elderly. Clin Infect Dis. 2000;31:148.

20. Lee, CC, et al. Comparison of clinical manifestations and outcome of community-acquired bloodstream infections among the oldest old, elderly, and adult patients. Medicine (Baltimore). 2007;86:138.

21. Rich, MW. Epidemiology, clinical features, and prognosis of acute myocardial infarction in the elderly. Am J Geriatr Cardiol. 2006;15:7.

22. Alexander, KP, et al. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part I: Non–ST-segment-elevation acute coronary syndromes: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: In collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115:2549.

23. Alexander, KP, et al. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part II: ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: A scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology: In collaboration with the Society of Geriatric Cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115:2570.

24. Marco, CA, et al. Fever in geriatric emergency patients: Clinical features associated with serious illness. Ann Emerg Med. 1995;26:18.

25. Juthani-Mehta, MA. Symptomatic bacteriuria and urinary tract infection in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2007;23:585.

26. Lewis, LM, et al. Etiology and clinical course of abdominal pain in senior patients: A prospective, multicenter study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60:1071.

27. Kim, AY, Ha, HK. Evaluation of suspected mesenteric ischemia: Efficacy of radiologic studies. Radiol Clin North Am. 2003;41:327.

28. Hustey, FM, et al. The use of abdominal computed tomography in older ED patients with acute abdominal pain. Am J Emerg Med. 2005;23:259.

29. Aschkenasy, MT, Rothenhaus, TC. Trauma and falls in the elderly. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2006;24:413.

30. Soriano, TA, DeCherrie, LV, Thomas, DC. Falls in the community-dwelling older adult: A review for primary-care providers. Clin Interv Aging. 2007;2:545.

31. Cook, LJ, et al. Motor vehicle crash characteristics and medical outcomes among older drivers in Utah, 1992-1995. Ann Emerg Med. 2000;35:585.

32. Rathlev, NK, et al. Intracranial pathology in elders with blunt head trauma. Acad Emerg Med. 2006;13:302.

33. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Public health and aging: Influenza vaccination coverage among adults aged > or = 50 years and pneumococcal vaccination coverage among adults aged > or = 65 years—United States, 2002. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:987.