Chapter 39 The Difficult Airway in Conventional Head and Neck Surgery

I Introduction

Acute airway situations in head and neck surgery should be approached in a systematic manner. The simplest adequate form of control should be selected, and the lowest level (i.e., supraglottis, glottis, subglottis, or trachea) of airway obstruction should be ascertained; control should be established by securing an airway below that level. Acute airway problems often evolve in association with other medical problems. Obvious and potential difficult mask ventilation or difficult intubation should be discussed with the head and neck surgeon, and thoughtful discussion about sequential steps of airway management should take place before anesthetic induction and especially before attempting intubation. Ideally, if time allows, an action plan addressing airway management, including the initial strategy and two backup measures, should be communicated to all team members in the room. Maintaining lines of communication during the intubation procedure can reduce morbidity and mortality associated with difficult airway management.1

The severity or completeness of airway obstruction is categorized as follows:

1. Complete obstruction: no detectable airflow in or out of lungs

2. Partial obstruction: patient with stridor or dyspnea from narrowing of the major airway

3. Potential or impending obstruction: concern that a patient will develop airway compromise because of a known anatomic or physical condition if the respiratory physiology or the consciousness level is altered

II AerodigestIVe Oncologic Surgery

A Preoperative Airway Assessment

1 History

Tobacco and alcohol use are associated with most cases of head and neck cancer and predispose these patients to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pneumonia, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and alcohol withdrawal. Information about previous surgical and anesthetic procedures with an emphasis on a history of anesthetic difficulties or difficult intubations, or both, must be obtained and communicated. Previous difficult airway management is considered to be one of the most important predictors of subsequent airway management difficulties.2,3 Patients with a history of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), especially those without an obvious anatomic abnormality, need careful assessment because their redundant pharyngeal mucosa and soft palate anatomy may hinder BMV and the ability to intubate. Common presenting symptoms of airway obstruction include dyspnea at rest or on exertion, voice changes, dysphagia, stridor, and cough. Physical findings may include hoarseness; agitation; and intercostal, suprasternal, and supraclavicular retraction. Voice changes provide an early suggestion of the anatomic level and severity and progression of the lesion. A muffled voice may indicate supraglottic disease, whereas glottic lesions often result in a coarse, scratchy voice. If there is suspicion of an anterior mediastinal, pharyngeal, or neck mass resulting in partial airway obstruction, initiating anesthesia in the patient in the supine position without first securing the airway may lead to complete airway obstruction and therefore deserves special preoperative evaluation.

2 Physical Examination

A systematic and comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s upper airway is mandatory. The condition of dentition, facial hair (beard), size and mobility of the tongue, thyromental distance, Mallampati score, and limitations in neck flexion and extension must be evaluated. A thyrocervical distance of less than 6 cm in a fully extended adult neck is a good indicator of difficult laryngoscopy and an inability to visualize the vocal cords. The presence and character of stridor should be appreciated, because it may suggest the location of airway narrowing (Table 39-1). Postirradiation changes, neck masses, and previous neck surgery may result in reduced neck mobility, causing difficult mask ventilation and difficult intubation. Findings of morbid obesity, evidence of any oropharyngeal or lip edema, and signs of upper aerodigestive tract bleeding may direct the preferred method of airway management. Lower cranial nerve dysfunction from tumor or previous surgery may also result in airway difficulty related to aspiration or obstruction.

| Factor | Features |

|---|---|

| Definition |

B Securing the Airway

There are many approaches to securing the airway of patients undergoing head and neck surgery in a safe manner. Determining the optimal approach may depend on the surgery being performed, location of a lesion or infectious mass, or tolerance of the patient. For example, in a patient undergoing maxillomandibular fixation to repair a fractured mandible, nasotracheal intubation is ideal to keep the endotracheal tube (ETT) out of the oral cavity. In a patient with severe supraglottic angioedema, flexible fiberoptic intubation through the nose with the patient upright is preferred to enable identification of the airway with fiberoptic visualization and to avoid pharyngeal collapse in the supine position. Establishing a sequential airway plan with backup options and open communication between the anesthesiology and surgical teams facilitate preparedness and patient safety. An analysis of anesthesia-related cardiopulmonary arrests revealed that up to one third of severe complications result from an inability to establish an optimal airway after the induction of general anesthesia.4

1 Examination of the Airway in the Awake Patient

For a potentially difficult airway, the anesthesiologist may elect to evaluate the airway in an awake patient with the help of judicious intravenous sedation and topical anesthesia. This assessment helps to determine the optimal approach to securing the airway without compromising the patient’s spontaneous breathing. The successful execution of this technique requires constant meaningful contact with the patient and adequate use of topical agents, such as 4% lidocaine spray, with the ultimate goal of not compromising the ability of the patient to breathe spontaneously and to protect the airway. Percutaneous blocks of the superior laryngeal nerves or translaryngeal instillation of lidocaine is best avoided in patients with a head or neck tumor. After the patient is adequately prepared, careful direct laryngoscopy is performed to assess whether to proceed with an awake intubation or to induce general anesthesia for subsequent intubation. A reasonable airway in an awake patient may change to a compromised airway immediately after induction of general anesthesia, with loss of tone of the pharyngeal wall and anterior displacement of the larynx.5 If direct laryngoscopy with sedation is too risky to perform, consideration should be given to awake, flexible fiberoptic laryngoscopy to assess the airway and the possibility of awake, nasotracheal, flexible fiberoptic intubation.

2 Choice of Endotracheal Intubation Technique

a Endotracheal Intubation after Induction of General Anesthesia

In patients with no obvious or expected airway compromise, the ETT can be placed during direct laryngoscopy after induction with a short-acting paralyzing agent, such as succinylcholine. Because it is difficult or impossible to empty the stomach with a nasogastric tube in the case of a large pharyngeal or esophageal tumor, the patient is assumed to have a full stomach.6 Risk of aspiration is reduced by preinduction administration of ranitidine, metoclopramide, and oral sodium citrate–citric acid buffer (Bicitra, Willen Drug Co., Baltimore, MD). The Hollinger anterior commissure laryngoscope is a valuable tool in difficult airway management, and it should be considered when other techniques have failed. This scope may accommodate a 5.0-mm or smaller cuffed ETT, but the insufflation port may become lodged in the barrel of the scope. To avoid this issue, a trial passage of the ETT through the laryngoscope should be attempted before the performance of direct laryngoscopy.7

b Nasotracheal Intubation in the Awake Patient

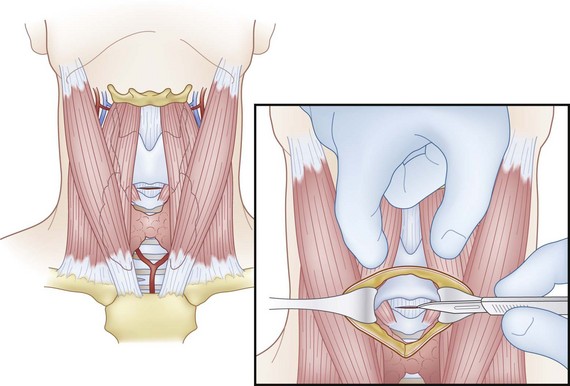

The nasotracheal route is useful in cases of small mouth opening, severe trismus, large tongue, receding lower jaw, large oral cavity tumor, planned maxillomandibular fixation, or tracheal dilatation. Operator and equipment positioning relative to the patient is depicted in Figure 39-1. For nasal intubation, the nose is prepared with a nasal decongestant spray, such as pseudoephedrine (Afrin) and topical 4% cocaine. Cocaine is more advantageous than lidocaine because it is a vasoconstrictor in addition to being a very effective surface anesthetic. The potential for abuse by the personnel is occasionally a deterrent for its routine use. In placing the ETT through the nose, it is necessary to remember that the nasal floor usually runs in a horizontal plane perpendicular to an imaginary vertical line connecting the glabella and the pogonion. The ETT is advanced to approximately the 15-cm mark, and the connector is removed. The flexible fiberoptic bronchoscope (FFB) is then used to visualize the glottic opening and to introduce the tube into the trachea.

d Rigid Bronchoscopy

The rigid bronchoscope, a hollow stainless steel tube through which a rigid telescope is placed, provides excellent access to the airways. The distal end of the rigid bronchoscope is usually beveled to facilitate intubation and lifting of the epiglottis. The updated American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) protocol states that in the “cannot intubate, cannot ventilate” (CICV) scenario, “a rigid bronchoscope for difficult airway management reduces airway-related adverse outcomes.”8 This modality is recommended as a technique for cases of difficult mask ventilation. Other indications for rigid bronchoscopy include massive airway hemoptysis, foreign body retrieval, laser or photodynamic therapy, and placement of airway stents.9

e Retrograde Intubation

Though rarely used, retrograde intubation represents another alternative technique for intubation of the difficult airway in head and neck patients. This technique can also be used in patients with trismus, trauma to the cervical spine, temporomandibular joint ankylosis, upper airway masses, or failed intubation. This technique begins with puncture of the cricothyroid membrane (CTM) or cricotracheal membrane with a small needle angled superiorly to pass a guidewire through the larynx, and it is then guided through the nose or mouth. The ETT is then advanced over the guidewire with a Seldinger technique into position in the trachea.10

Retrograde intubation may also be used to facilitate other approaches. For example, a combination of conventional, fiberoptic, and retrograde techniques can be used to intubate successfully.11 An FFB with a suction port can be used as an anterograde guide over a retrograde wire. A direct laryngoscopic view can facilitate placement of the tip of a fiberoptic scope into or near the glottic aperture. After the FFB is past the vocal folds and tracheal rings have been identified, the preloaded ETT may be passed over the FFB into the trachea.

f Tracheostomy with Local Anesthesia

If a patient is in acute respiratory distress because of upper airway obstruction and the patient is considered unable to be safely intubated under general anesthesia after evaluation (including FFB), the best choice is to perform a planned but urgent awake tracheostomy.12 This should be performed under local anesthesia with minimal intravenous sedation to avoid loss of spontaneous breathing. Tracheostomy under local anesthesia in an awake patient is also an excellent method to secure the airway in the following situations: upper airway abscess that may be in the way of or distorting the pathway for endotracheal intubation; bulky, friable supraglottic or glottic mass; and glottic stenosis with presumed bilateral cricoarytenoid joint fixation. In these situations, attempts at direct laryngoscopy and intubation may result in abscess rupture or aspiration of purulent material, blood, or material from a friable tumor, or in the case of cricoarytenoid joint fixation, the fixed, medialized vocal folds do not allow passage of the ETT without severe damage to the membranous vocal folds.

3 Difficult or Failed Intubation

a Adequate Bag-Mask Ventilation

As an alternative, in a patient who is adequately BMV, the ETT may be passed with oral fiberoptic-guided laryngoscopy.13 An OPA bite block is placed in the patient’s mouth, and the regular mask is replaced with an endoscopy port (i.e., Patil-Syracuse endoscopy mask).14 The lubricated FFB is passed through the mask’s diaphragm into the OPA and into the trachea through the glottis. The ETT is then threaded over the FFB into the patient’s trachea. As described earlier, a scope can also be used to pass an ETT through the nose. The nose is decongested with topical Afrin, and topical 4% cocaine is used to anesthetize the nose. The appropriately sized, well-lubricated ETT is then placed along the floor of the nose, and an FFB is passed through the tube. An assistant occludes the other nostril and the mouth, and a triple connector is used so that the scope and O2 delivery can be simultaneously introduced.

b Failed Bag-Mask Ventilation

In situations of inadequate BMV of an anesthetized patient, after unsuccessful attempts at chin thrust and placement of a nasopharyngeal airway or OPA, the ASA algorithm should be followed.8 The laryngeal mask airway (LMA) was integrated into the ASA difficult airway algorithm in different locations in 1996,15 as a supralaryngeal airway or ventilation device or as an intubation conduit. If LMA ventilation is not adequate or feasible, the emergency pathway should be followed, and if the patient cannot be ventilated with a bag-mask or awakened safely, emergency surgical airway remains the next option (see Chapters 10 and 31). Use of LMAs is increasing in many situations of inadequate BMV,16,17 but they should be used with extreme caution in conventional head and neck surgery, even by those with adequate experience with these devices. If ventilation with the LMA is the only option, we recommend definitive endotracheal intubation before initiation of surgery by advancing an ETT through the LMA or advancing an Aintree intubation catheter (Cook Critical Care, Bloomington, IN) over an FFB passed through the LMA into the trachea. In the latter case, the LMA is then removed, and an ETT is passed over the Aintree catheter and into the trachea. It should be kept in mind that only ETTs 7.0 mm or larger can be used with this technique.

4 Cricothyrotomy

Cricothyrotomy (i.e., coniotomy) is a procedure for establishing an emergency airway when other methods are unsuitable or impossible. Emergency cricothyrotomy is performed in approximately 1% of all emergency airway cases in the emergency department.18 The access site is the CTM. This procedure is especially suited for gaining control of the airway when severe hemorrhage or massive facial trauma, foreign bodies, or emesis does not permit visualized intubation. Other cases arise when teeth are clenched, when intubation repeatedly fails, and when there is a possibility of cervical spine injury. In these cases, cricothyrotomy represents the safest and quickest way to obtain an airway because minimal soft tissue dissection is required between the skin and the CTM.19 If a patient has sustained a respiratory insult associated with burns or smoke inhalation, an elective prophylactic cricothyrotomy may be performed early to prevent fatal respiratory obstruction occurring during transport.20

a Surgical Technique

The CTM is identified by palpating a slight indentation in the skin superior to the prominence of the cricoid cartilage. The CTM is immediately subcutaneous with no overlying large veins, muscles, or fascial layers, allowing easy access. A vertical skin incision and a horizontal entrance into the CTM are advised. For an incision into the CTM itself, a low horizontal stab is made to avoid laterally placed vessels.21 A small tracheostomy tube or a small standard ETT can be used in a cricothyrotomy. If an ETT is placed through the cricothyrotomy, it should be minimally advanced so it does not enter a bronchus because of the short distance between the CTM and carina. Tube size is important in ensuring successful cannulation without excessive trauma. After the patient is stabilized, the cricothyrotomy should be converted to a formal tracheotomy for adequate ventilation and to minimize risk of injury to the vocal folds, which attach into the thyroid cartilage just superior to the CTM (Fig. 39-2). This technique is contraindicated in patients who are at increased risk for subglottic stenosis, preexisting laryngeal disease, malignancy, nearby inflammatory processes, epiglottitis, severe distortion of normal anatomy, or bleeding diathesis and contraindicated in infants and children.22

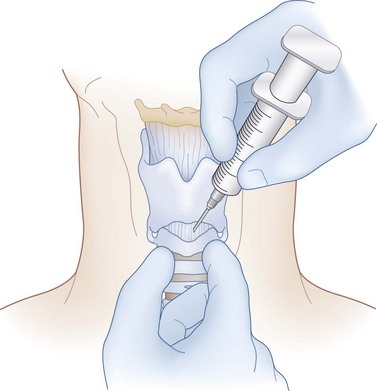

b Needle Technique

Needle cricothyrotomy is performed in dire emergencies when the appropriate equipment or knowledge to perform a formal emergency cricothyrotomy or intubation is unavailable or in children younger than 2 years with airway obstruction and an inability to be intubated. A large-gauge needle and cannula with a syringe attached are introduced through the CTM until air can be aspirated. The cannula is then advanced off the needle down the airway (Fig. 39-3). The cannula is connected to an oxygen supply. The patient can then be oxygenated, but ventilation to remove carbon dioxide (CO2) is not achieved, and respiratory acidosis may ensue rapidly. A needle cricothyrotomy ensures a supply of O2 for a short time only, and it must be converted to a surgical cricothyrotomy or tracheotomy in a timely fashion to allow adequate ventilation.23

The transtracheal needle ventilation technique can be used to great advantage in the emergency setting. This technique requires access to 100% O2 at 50 psi and a Luer-Lok connector. Adequate ventilation through the catheter is not possible with a conventional ventilator or a handheld anesthesia bag.24 The airway is controlled by puncturing the trachea or CTM with a 16-gauge, plastic-sheathed needle. The needle is withdrawn, leaving the sheath in the trachea; the sheath is then attached to the high-pressure line through a pressure regulator control, and ventilation is accomplished using a manual interrupter switch. The patient can be fully ventilated with this technique for only 45 minutes. The only way the gas or O2 inspired through transtracheal jet ventilation (TTJV) can escape is through the patient’s own airway, and attempts at securing the airway must continue. The equipment to perform adequate TTJV should be available in the operating room, and the anesthesiology team should familiarize themselves with its assembly.

5 Percutaneous Dilatational Tracheostomy

Percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy (PDT) is placement of a tracheostomy tube without direct surgical visualization of the trachea. The general consensus is that PDT should be performed only on intubated patients.25 It is considered to be a minimally invasive bedside procedure that is easily performed in the intensive care unit (ICU) or ward, with continuous monitoring of the patient’s vital signs.7 The criteria for PDT are more stringent than those for open surgical tracheostomy.26 A PDT should be performed on patients whose cervical anatomy can be clearly defined by palpation through the skin. Moreover, two preoperative criteria must be met: the ability to hyperextend the neck and ensuring that the patient can be reintubated in case of accidental extubation. Obese patients, children, and those with severe coagulopathies should not be considered candidates for this procedure (Table 39-2).26

TABLE 39-2 Contraindications to Percutaneous Dilatational Tracheostomy

| Absolute Contraindications | Relative Contraindications |

|---|---|

Several systems and approaches for performing a percutaneous tracheostomy have been marketed since the inception of the idea, and many comprehensive accounts of the evolution of this approach are available in the literature. Controversy surrounding this procedure lingers, but there have been many large series with acceptable rates of complications as long as proper selection of patients and adherence to a procedural protocol are ensured.27

Ciaglia and colleagues described a technique in which there is no sharp dissection beyond the skin incision.28 The procedure is done with the patient under general anesthesia, and all steps are performed under bronchoscopic vision. The patient is positioned and prepared in the same fashion as for a standard surgical tracheostomy. A skin incision is made, and the pretracheal tissue is cleared with the help of blunt dissection. The ETT is withdrawn enough to place the cuff at the level of the glottis. The endoscopist places the tip of the bronchoscope such that the light from the tip shines through the surgical wound. The operator then enters the tracheal lumen below the second tracheal ring with an introducer needle. The track between the skin and the tracheal lumen is serially dilated over a guidewire and stylet. A tracheostomy tube is placed under direct bronchoscopic vision over a dilator. Placement of the tube is confirmed again by visualizing the tracheobronchial tree through the tube. The tube is then secured to the skin with sutures and tracheostomy tape.

In another technique for percutaneous tracheostomy, Schachner and colleagues made a small skin incision and passed a dilator tracheotome (Rapitrac) over a guidewire into the trachea to dilate the tract fully in one step.29 The tracheotome has a beveled metal core with a hole through its center that accommodates a guidewire. Inside the trachea, the tracheotome is dilated, and a conventional tracheotomy cannula fitted with a special obturator is passed through the tracheal opening. The dilator and obturator are then removed.

A novel method called translaryngeal tracheostomy (i.e., Fantoni’s technique) is different from other techniques. For Fantoni’s tracheostomy, the initial puncture of the trachea is carried out with the needle directed cranially and the tracheal cannula inserted with a pull-through technique along the orotracheal route in a retrograde fashion. The cannula is then rotated downward using a plastic obturator. The main advantage of Fantoni’s tracheostomy is that a minimal skin incision is required, and almost no bleeding is observed.30,31 The procedure can be carried out only under endoscopic guidance, and rotating the tracheal cannula downward may pose a problem, demanding more experience.

The routine use of bronchoscopy during PDT, other than Fantoni’s tracheostomy, is controversial.32,33 There are reports of lower rates of acute complications under endoscopic guidance.33 For critically ill patients or those with head injuries, it is important to consider the resultant hypercarbia when choosing to perform an endoscopically guided PDT. However, endoscopic guidance plays a critical role in the training of physicians, during percutaneous tracheostomy in patients with complex anatomy, and in removing aspirated blood. Another consideration that supports the use of bronchoscopy is the ability to better define the exact location of the tracheal puncture.34 A cadaver study in autopsies of patients who had undergone PDT found that the tracheal puncture site varied greatly.35 It seems logical that bronchoscopic guidance during PDT can confirm the initial airway puncture site, although a controlled study is necessary to settle this issue.34

The technique of PDT is relatively easy to learn, but it has been repeatedly reported that a learning curve exists, which may be overcome by performing a number of supervised procedures. The time required for performing a bedside PDT is considerably shorter than that required for performing an open tracheostomy.36 In ICU patients, one of the major advantages of PDT is elimination of the scheduling difficulty associated with the operating room and anesthesiology teams. Bedside PDT also precludes the necessity to schedule the surgery and to transport critically ill patients who require intensive monitoring to and from the operating room.37 PDT expedites the performance of the procedure in most cases. The cost of performing a PDT is roughly one half that of an open surgical tracheostomy. The major savings are operating room charges and anesthesia fees.38

C Intraoperative Airway Management

III Extubation in Head and Neck Surgery

A Planned Extubation of the Endotracheal Tube

To ensure a safe extubation, the anesthesiology team should consider the following questions. First, is there an air leak around the tube after deflating the cuff? Second, if the patient develops acute airway obstruction on extubation, are the equipment and personnel available to secure an airway to prevent hypoxia? This may include options for an emergency cricothyrotomy, TTJV, or a tracheostomy. If the answer is an affirmative, extubation should proceed. If the preceding criteria cannot be met, extubation should be delayed for another 24 hours, or the anesthesiologist should consider extubating over an airway exchange catheter (AEC) or a jet stylet.39 A hollow AEC with a small internal diameter is inserted through the ETT into the patient’s trachea. The ETT is then withdrawn over the catheter; the AEC can be used as a means of jet ventilation or a reintubation guide, or both.11 This approach is especially useful when an ETT needs to be exchanged or replaced.

IV Tonsillectomy and Other Oropharyngeal Procedures

A Preoperative Considerations

Tonsillectomy is one of the most frequent procedures performed by the otolaryngologist, with about 737,000 performed in 2006.40 Most of these operations are performed on healthy adults and children. Current indications include history of recurrent tonsillitis, tonsillar hypertrophy, OSA, asymmetrical tonsils, recurrent peritonsillar abscess, and tonsillar malignancy.41 Performance of these procedures in patients with coagulation disorders is uncommon but can be challenging if the diagnostic workup fails to alert the surgical and anesthesiology teams about the presence, nature, and extent of the problem.

B Obstructive Sleep Apnea

OSA can lead to serious and potentially life-threatening conditions if left untreated. They include hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, coronary artery disease, cor pulmonale, and congestive heart failure.42 Nonsurgical options are available for patients with mild to moderate sleep apnea, but many patients with severe sleep apnea, tonsillar hypertrophy, and soft palate redundancy can benefit from tonsillectomy, uvulectomy, and uvulopalatopharyngectomy. Adults with this disorder must have a preoperative assessment of the severity of the problem with an overnight polysomnogram. The severity of OSA, the extent of desaturation, and the number and duration of apneic episodes have significant implications, especially for postoperative monitoring of these patients. Induction of general anesthesia relaxes the pharyngeal muscles in a manner similar to the effect of rapid-eye-movement (REM) sleep.39 This makes BMV difficult to maintain, and the OPAs and nasopharyngeal airways do not always significantly improve the airway. Excessive pharyngeal tissue exacerbates the obstruction caused by the redundant soft palate and base of the tongue, hindering a good view of the cords during laryngoscopy. Patients with OSA are more sensitive to sedative and narcotic analgesics. This necessitates extreme caution and a need for slow titration in using these agents. Awake fiberoptic intubation may be considered before induction of general anesthesia.

C Peritonsillar and Parapharyngeal Abscess

Anesthetic management of patients with peritonsillar abscess is a challenging task in head and neck surgery. These patients have severe odynophagia, upper airway edema, and distortion of the normal anatomy. The limited mouth opening resulting from local pain and inflammation increases the degree of difficulty when securing the airway. The anesthesiologist should expect a difficult airway on induction of general anesthesia and make alternative plans to be able to achieve a secure airway. Spontaneous or traumatic rupture of the abscess is a real risk, and the consequential aspiration of pus into an unprotected airway remains a possibility. The head and neck surgeon may attempt needle aspiration for decompression of the abscess under local anesthetic.43 Awake intubation or direct laryngoscopy is a safe option only if the abscess is relatively small and does not distort the route of intubation. A possible alternative is nasal, awake fiberoptic intubation using topical anesthesia. Topical anesthesia can be accomplished using the “spray-as-you-go” technique or translaryngeal injection of 3 to 4 mL of 4% lidocaine.13 For a sizable abscess or airway distortion, a tracheostomy done under local anesthesia with minimal or no sedation is the safest approach.

D Airway Management During Routine Tonsillectomy and Oral Procedures

The surgeon places a mouth gag (e.g., Crowe-Davis) into the mouth to increase exposure of the oropharynx. The ETT is held in a groove under the blade of this gag. There is a small but real danger of extubation during placement, adjustment, and removal of this blade. The ETT should always be secured with a tape to the lower lip. To monitor for kinking or obstruction of the ETT, the anesthesiologist must pay close attention to EtCO2, bilateral chest auscultation, and peak airway pressures. The oral cavity and oropharynx should be gently but meticulously suctioned at the end of the procedure to prevent aspiration of blood, causing laryngospasm. The patient’s head should be turned to the side at the end of the procedure to minimize blood in the endolarynx and resultant laryngospasm.29

E Postoperative Airway Problems After Tonsillectomy

Monitoring patients for OSA after tonsillectomy has been a controversial issue. Children with severe and mixed (obstructive and central) sleep apnea should be monitored overnight in a postanesthesia care unit (PACU).44 Relief of airway obstruction increases the risk of postoperative pulmonary edema and does not address central apneic episodes, which may be unmasked and result in O2 desaturation and loss of respiratory drive.44 The postoperative care of adults with OSA after tonsillectomy and similar procedures should be individualized. Care should be based on the severity of sleep apnea preoperatively and performance in the PACU in the immediate postoperative period.

F Management of Bleeding After Tonsillectomy

Post-tonsillectomy bleeding may take place in the immediate postoperative period (i.e., reactionary bleeding) or 7 to 10 days after the surgery (i.e., secondary bleeding, often from infection). Preventive measures, such as meticulous hemostasis for reactionary bleeding and hydration and administration of oral antibiotics for secondary bleeding, are routinely recommended by surgeons. Obstruction of the airway by a combination of bleeding and postoperative airway edema is the most frequent cause of post-tonsillectomy morbidity.45 Post-tonsillectomy bleeding occurs usually at a slow rate, allowing a large volume of blood to be swallowed by the patient without awareness. Postoperative nausea and vomiting and loss of blood may result in severe hypovolemia before a fall in the hemoglobin level is detected. Reduced hemoglobin level and aspiration of blood may result in hypoxemia in the patient, especially in a young child. Careful serial monitoring of hemoglobin levels and judicious use of packed red cell transfusions are important considerations, particularly in children.

If surgical treatment is required for post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage, the patient should be assumed to have a full stomach with blood in the airway.39 Awake intubation under direct laryngoscopy in adults or rapid-sequence induction of anesthesia with etomidate or ketamine is the preferred choice in this situation. A work-up for coagulation disorders should take place in case of recurrent hemorrhage. An angiogram or a CT scan to rule out a pseudoaneurysm of the carotid may be needed in rare cases of recurrent and severe post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage.

V Surgery on the Anterior Skull Base

The scope of head and neck surgery has expanded to include craniofacial, maxillofacial, and anterior skull base surgery. Indications may include trauma, syndromic skeletal abnormalities, sleep apnea, orthognathic deformities, and tumor removal. The anesthetic team must discuss and understand the approach, nature, and extent of the proposed surgical procedure to be able to anticipate airway problems.46 Most patients undergoing these procedures are previously healthy adults or children, but a few have anatomic abnormalities that predispose them to challenging airway problems, including limited mouth opening, retrognathia, protruded maxilla, and presence of orthodontic appliances.47

VIII Clinical Pearls

• The risk of a difficult airway is relatively high for patients undergoing head and neck surgery.

• Communication during the intubation procedure reduces the morbidity and mortality associated with difficult airway management.

• The optimal approach to securing the airway of patients undergoing head and neck surgery depends on the operation being performed, location of the lesion or infectious mass, tolerance of the patient, and comfort level of the anesthesiology and otolaryngology team.

• Establishing a sequential airway plan with backup options optimizes patient safety.

• The Hollinger anterior commissure laryngoscope is one of the most useful tools for difficult airway management, and it should be considered when other techniques for orotracheal intubation have failed.

• Nasotracheal fiberoptic intubation is useful in cases of a small mouth opening, severe trismus, large tongue, receding lower jaw, large oral cavity tumor, planned maxillomandibular fixation, or tracheal dilatation.

• If a patient is in acute respiratory distress because of upper airway obstruction and is unable to be safely intubated under general anesthesia, the best choice is to perform a planned but urgent awake tracheostomy.

• Cricothyrotomy is a procedure for establishing an emergency airway when other methods are unsuitable or impossible.

All references can be found online at expertconsult.com.

1 Arriaga AF, Elbardissi AW, Regenbogen SE, et al. A policy-based intervention for the reduction of communication breakdowns in inpatient surgical care: Results From a Harvard Surgical Safety Collaborative. Ann Surg. 2011;253:849–854.

4 Keenan RL, Boyan CP. Cardiac arrest due to anesthesia. A study of incidence and causes. JAMA. 1985;253:2373–2377.

7 Bhatti NI. Surgical management of the difficult adult airway. In: Flint PW, ed. Cummings otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. ed 5. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010:121–129.

8 Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1269–1277.

11 Benumof JL. Management of the difficult adult airway. With special emphasis on awake tracheal intubation. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:1087–1110.

15 Benumof JL. Laryngeal mask airway and the ASA difficult airway algorithm. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:686–699.

20 Milner SM, Bennett JD. Emergency cricothyrotomy. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:883–885.

37 Freeman BD, Isabella K, Cobb JP, et al. A prospective, randomized study comparing percutaneous with surgical tracheostomy in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:926–930.

39 Kirk GA. Anesthesia for ear, nose, and throat surgery. In: Rogers MC, Tinker JH, Covino BG, Longnecker DE, eds. Principles and practice of anesthesia, vol 2. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993:2257–2274.

43 Donlon JV, Jr. Anesthesia for eye, ear, nose, and throat surgery. In: Miller RD, ed. Anesthesia, vol 2. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1990:2001–2023.

1 Arriaga AF, Elbardissi AW, Regenbogen SE, et al. A policy-based intervention for the reduction of communication breakdowns in inpatient surgical care: Results From a Harvard Surgical Safety Collaborative. Ann Surg. 2011;253:849–854.

2 Pearce A. Evaluation of the airway and preparation for difficulty. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2005;19:559–579.

3 Schaeuble JC, Caldwell JE. Effective communication of difficult airway management to subsequent anesthesia providers. Anesth Analg. 2009;109:684–686.

4 Keenan RL, Boyan CP. Cardiac arrest due to anesthesia. A study of incidence and causes. JAMA. 1985;253:2373–2377.

5 Sivarajan M, Fink BR. The position and the state of the larynx during general anesthesia and muscle paralysis. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:439–442.

6 Banoub MN, Nugent M. Thoracic anesthesia. In: Rogers MC, Tinker JH, Covino BG, Longnecker DE, eds. Principles and Practice of Anesthesia, vol 2. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993:1719–1930.

7 Bhatti NI. Surgical management of the difficult adult airway. In: Flint PW, ed. Cummings otolaryngology-head and neck surgery. ed 5. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010:121–129.

8 Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1269–1277.

9 Chao YK, Liu YH, Hsieh MJ, et al. Controlling difficult airway by rigid bronchoscope—An old but effective method. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2005;4:175–179.

10 Dhara SS. Retrograde tracheal intubation. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:1094–1104.

11 Benumof JL. Management of the difficult adult airway. With special emphasis on awake tracheal intubation. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:1087–1110.

12 Altman KW, Waltonen JD, Kern RC. Urgent surgical airway intervention: A 3 year county hospital experience. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:2101–2104.

13 Ovassapian A, Tuncbilek M, Weitzel EK, et al. Airway management in adult patients with deep neck infections: A case series and review of the literature. Anesth Analg. 2005;100:585–589.

14 Patil VU. Concerning the complications of the Patil-Syracuse Mask. Anesth Analg. 1993;76:1165–1166.

15 Benumof JL. Laryngeal mask airway and the ASA difficult airway algorithm. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:686–699.

16 Calder I, Ordman AJ, Jackowski A, et al. The Brain laryngeal mask airway. An alternative to emergency tracheal intubation. Anaesthesia. 1990;45:137–139.

17 de Mello WF, Ward P. The use of the laryngeal mask airway in primary anaesthesia. Anaesthesia. 1990;45:793–794.

18 Bair AE, Panacek EA, Wisner DH, et al. Cricothyrotomy: A 5-year experience at one institution. J Emerg Med. 2003;24:151–156.

19 Collicott PA, Aprahamian C, Carrico CJ. Upper airway management. In: Advanced trauma life support. Chicago: American College of Surgeons; 1984:155–161.

20 Milner SM, Bennett JD. Emergency cricothyrotomy. J Laryngol Otol. 1991;105:883–885.

21 Matthews HR, Hopkinson RB. Treatment of sputum retention by minitracheotomy. Br J Surg. 1984;71:147–150.

22 Schroeder AA. Cricothyroidotomy: When, why, and why not? Am J Otolaryngol. 2000;21:195–201.

23 Goldenberg D, Bhatti NI. Management of the impaired airway in the adult. In: Flint PW, ed. Cummings otolaryngology–head and neck surgery. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2010:2441–2453.

24 Benumof JL, Scheller MS. The importance of transtracheal jet ventilation in the management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 1989;71:769–778.

25 Goldenberg D, Golz A, Huri A, et al. Percutaneous dilation tracheotomy versus surgical tracheotomy: Our experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:358–363.

26 Couch ME, Bhatti N. The current status of percutaneous tracheotomy. Adv Surg. 2002;36:275–296.

27 Ciaglia P. Differences in percutaneous dilational tracheostomy kits [letter]. Chest. 2000;117:1823.

28 Ciaglia P, Firsching R, Syniec C. Elective percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy. A new simple bedside procedure; preliminary report. Chest. 1985;87:715–719.

29 Schachner A, Ovil Y, Sidi J, et al. Percutaneous tracheostomy—A new method. Crit Care Med. 1989;17:1052–1056.

30 Fantoni A, Ripamonti D. A non-derivative, non-surgical tracheostomy: The translaryngeal method. Intensive Care Med. 1997;23:386–392.

31 Oeken J, Adam H, Bootz F. Fantoni translaryngeal tracheotomy (TLT) with rigid endoscopic control [in German]. HNO. 2002;50:638–643.

32 Kost KM. Endoscopic percutaneous dilatational tracheotomy: A prospective evaluation of 500 consecutive cases. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:1–30.

33 Polderman KH, Spijkstra JJ, de Bree R, et al. Percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy in the ICU: Optimal organization, low complication rates, and description of a new complication. Chest. 2003;123:1595–1602.

34 Oberwalder M, Weis H, Nehoda H, et al. Videobronchoscopic guidance makes percutaneous dilational tracheostomy safer. Surg Endosc. 2004;18:839–842.

35 Walz MK, Schmidt U. Tracheal lesion caused by percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy—A clinico-pathological study. Intensive Care Med. 1999;25:102–105.

36 Massick DD, Powell DM, Price PD, et al. Quantification of the learning curve for percutaneous dilatational tracheotomy. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:222–228.

37 Freeman BD, Isabella K, Cobb JP, et al. A prospective, randomized study comparing percutaneous with surgical tracheostomy in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:926–930.

38 Cobean R, Beals M, Moss C, et al. Percutaneous dilatational tracheostomy. A safe, cost-effective bedside procedure. Arch Surg. 1996;131:265–271.

39 Kirk GA. Anesthesia for ear, nose, and throat surgery. In: Rogers MC, Tinker JH, Covino BG, Longnecker DE, eds. Principles and practice of anesthesia, vol 2. St. Louis: Mosby; 1993:2257–2274.

40 Cullen KA, Hall MJ, Golosinskiy A. Ambulatory surgery in the United States, 2006. Natl Health Stat Report. 2009;11:1–25.

41 Davidson TM, Calloway CA. Tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy—Its indications and its problems. West J Med. 1980;133:451–454.

42 Hall JB. The cardiopulmonary failure of sleep-disordered breathing. JAMA. 1986;255:930–933.

43 Donlon JV, Jr. Anesthesia for eye, ear, nose, and throat surgery. In: Miller RD, ed. Anesthesia, vol 2. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1990:2001–2023.

44 McColley SA, April MM, Carroll JL, et al. Respiratory compromise after adenotonsillectomy in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1992;118:940–943.

45 Crysdale WS, Russel D. Complications of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in 9409 children observed overnight. CMAJ. 1986;135:1139–1142.

46 Munro IR. Craniofacial surgery: Airway problems and management. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 1988;26:72–78.

47 Murphy A, Donoff B. Anesthesia for orthognathic surgery. Int Anesthesiol Clin. 1989;27:98–101.