CHAPTER 26 The Bernese Periacetabular Osteotomy for Hip Dysplasia and Acetabular Retroversion

Indications

Surgical technique

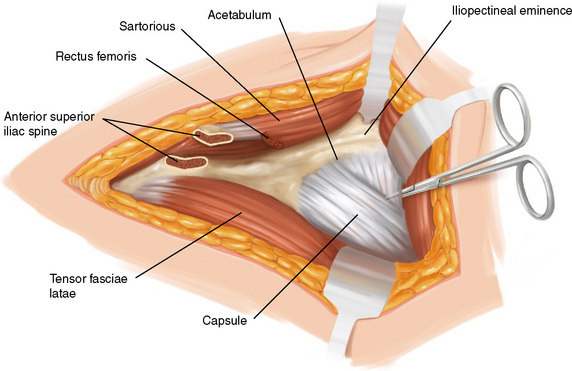

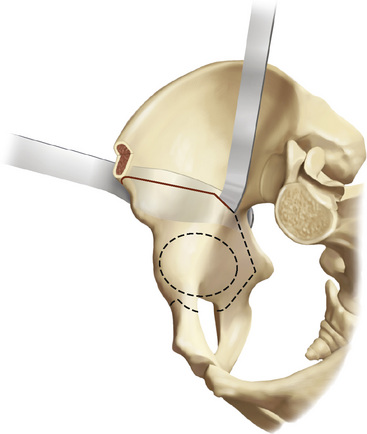

The iliocapsular muscle is detached from the capsule by sharp dissection going from lateral to medial until the iliopectineal bursa is opened and the psoas tendon becomes visible. The psoas tendon is undermined and retracted medially with the use of a pointed Hohmann retractor driven into the pubic ramus 1 cm to 1.5 cm medial to the iliopectineal eminence. The psoas tendon protects not only the femoral nerve but also the femoral vessels from overstretching; therefore, it should never be divided. The iliocapsularis muscle is now completely detached from the capsule, thus exposing the anteroinferior part of the capsule around the calcar. Any accidental opening of the capsule should be closed, because a closed capsule being put under tension facilitates the dissection of the ischial ramus. During this stage, a large, curved pair of scissors with rounded ends is advanced along the anteroinferior capsule, and the space between the capsule and the obturator externus is enlarged by spreading the scissors (Figure 26-1). The transversely running muscle belly of the obturator externus can often be seen. Because the medial femoral circumflex artery that supplies the femoral head runs distal to the muscle belly, scissors and other instruments must stay strictly proximal to the muscle belly. If visualization is impossible, it is safe to keep the instruments in close contact with the capsule.

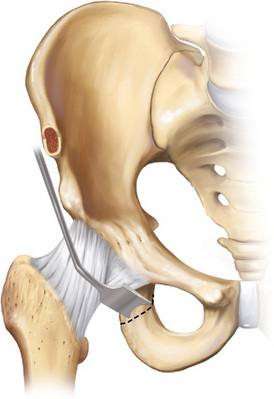

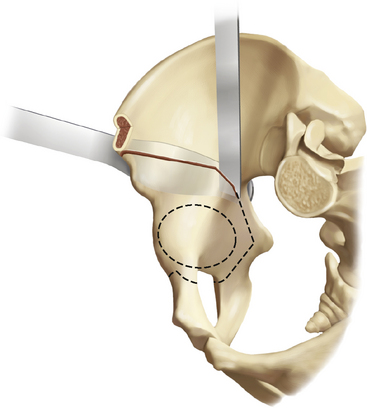

All osteotomies are performed with the patient’s hip in 45 degrees of flexion. The first cut is the partial osteotomy of the ischium (Figure 26-2). The scissors follow the capsule in a posterior direction until the ischial ramus is reached in the area of the infracotyloid notch. With the tip of the scissors, one can palpate the posterior and inferior border of the facies lunata of the acetabulum. The width of the ischium is assessed by gliding the scissors medially into the obturator foramen and then laterally until a soft resistance prevents further dissection. The soft-tissue resistance is formed by the tendinous origins of the ischiocrural muscles, which exceed the lateral border of the ischium when the hip is flexed. Respecting this resistance helps to avoid the lateral slipping of an instrument and thus protects the sciatic nerve. A large periosteal elevator or a Cobb elevator can be used to assist with the introduction of a 15-mm curved pelvic osteotome. The infracotyloid notch is palpated with the osteotome. The osteotome should point in the direction of the contralateral shoulder to avoid exiting through the lateral cortex and putting the sciatic nerve in danger. The handle of the osteotome points in a posteroinferior direction. The entry point of the osteotome is carefully made, and it is then driven slowly to a depth of 20 mm to 25 mm while the direction of the handle is gradually changed so that, at the end of the insertion, the handle points posterosuperiorly. At this stage, it is important to remember that the posterior column is not osteotomized completely. With wiggling motions, the osteotome is pulled back to the entry point, but the blade remains in contact with the bone. By doing this, one can feel whether the medial and lateral cortical borders are still intact. At the level of the entry point, the osteotome is moved carefully onto the remaining medial bone bridge and advanced with the same technique as used previously. The same technique is then applied to the lateral side. To relax and protect the sciatic nerve, the flexed hip has to be abducted and externally rotated. Of special importance is the fact that the medial cortex should be cut, whereas the lateral cortex should only be notched for the protection of the sciatic nerve. To determine whether the osteotomy is sufficiently deep and especially to be sure that the medial cortex is included in the osteotomy, the osteotomy is carefully repeated. The orientation as well as the depth of the partial osteotomy can be checked with the image intensifier. A sufficiently deep cut is the most important prerequisite for the problem-free displacement of the acetabulum at the end of all osteotomies.

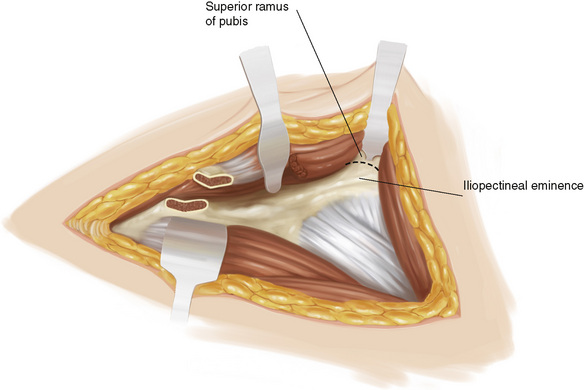

For the remaining three osteotomy steps, the approach to the quadrilateral plate is completed, and the abductors have to be tunneled. For the approach to the quadrilateral plate, the periosteum along the anterior surface of the anterior wall of the acetabulum, starting at the iliopectineal eminence, is incised and stepwise detached medially and inferiorly. Beyond the pelvic brim, the use of a curved periosteal elevator is recommended. To improve the stability of the reversed blunt Hohmann retractor positioned on the ischial spine, the dissection should not be carried out into the greater sciatic foramen. Having cleared the entire surface of the medial acetabular wall, the reversed blunt Hohmann retractor is inserted and levered against the ischial spine. The entire space up to the sacroiliac ligaments can now be viewed. Adduction of the flexed leg allows for the reduction of the soft-tissue tension (Figure 26-3).

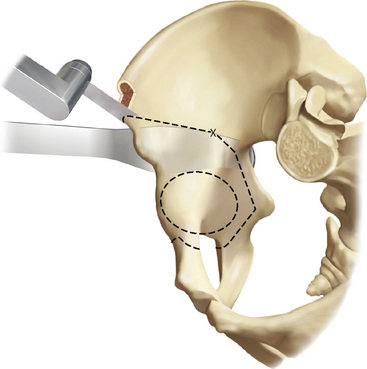

The supra-acetabular and retroacetabular osteotomies (i.e., the third and fourth steps) are performed in two parts. First, the planned line of osteotomy is marked on the inside of the ilium with a straight 10-mm Lexer osteotome. The marking starts on the lower border of the osteotomized ASIS and continues perpendicularly in a posterior direction, stopping short of the pelvic brim by 1.5 cm. The mark then continues, usually at an angle of 110 degrees to 120 degrees distally in the direction of the ischial spine. The determination of the apex and the degree of the angle can vary, depending on the patient’s anatomy. It is important that the retroacetabular cut be made at a distance of at least 1 cm away from the greater sciatic notch. With an oscillating saw, the first step—the supra-acetabular osteotomy—is performed (Figure 26-4). Second, with a curved Simal osteotome, the remaining distance to the pelvic brim is osteotomized at an angle of 110 degrees to 120 degrees to the first cut. The purpose of this cut is to osteotomize the bone completely; therefore, it is important that the curved retractor introduced on the external side of the pelvis remains in situ to protect the abductors and the sciatic nerve (Figure 26-5). With a straight Simal osteotome, the cortical bone of the quadrilateral plate is cut at a distance of approximately 1.5 cm anterior to the greater sciatic notch (Figure 26-6). Only the first 20 mm to 30 mm must be osteotomized; the remaining bony bridge in the direction of the sciatic spine will be broken later on in a controlled fashion. Because the subchondral bone of the joint and the rim of the greater sciatic notch are very hard, this controlled fracture always succeeds without extending into the joint or the greater sciatic notch.

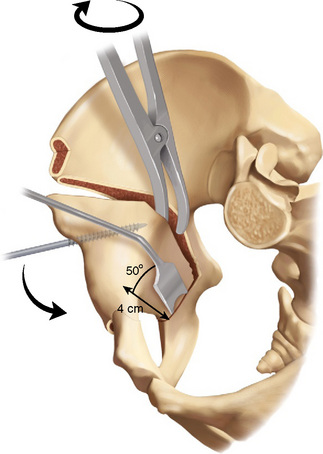

A 15-mm Lexer osteotome is introduced into the second posterior part of the osteotomy. By pulling the handle forward, a lever movement is exerted against the acetabulum until the bridge toward the sciatic spine breaks. If this maneuver does not succeed with moderate force, then the posterior part of the osteotomy should be extended more distally. The acetabulum is still attached to the pelvis at the posterior and caudal corner through a bone bridge between the first ischial cut and the posterior part of the supra-acetabular osteotomy. A Schanz screw is inserted through the AIIS into the supra-acetabular bone and parallel to the inner wall. The remaining bone bridge is now put under tension. With a spreader inserted into the posterior part of the supra-acetabular osteotomy and pulled through at the Schanz screw in a distal and lateral direction, the acetabulum is tilted distally and laterally; this allows for a better view of the quadrilateral plate. A 20-mm-wide angled pelvic osteotome is advanced 4 cm below the pelvic brim at an angle of 50 degrees to the quadrilateral plate in the direction of the endpoint of the first ischial osteotomy (Figure 26-7). The osteotome is advanced with careful hammer blows until resistance ceases. This is repeated two to three more times with more distal positioning of the osteotome. A decrease in tension is felt by less resistance at the Schanz screw and by a loosening of the spreader. Under no conditions should the chisel be advanced beyond the point at which no more resistance is felt because of the risk of injury to the sciatic nerve. The complete mobilization of the acetabular fragment is done by opposing the forces of the Schanz screw and the spreader: the Schanz screw is rotated forcefully medially, whereas the spreader is rotated externally to the outside of the pelvis. By doing this, the last part of the posteroinferior bone bridge is fractured.

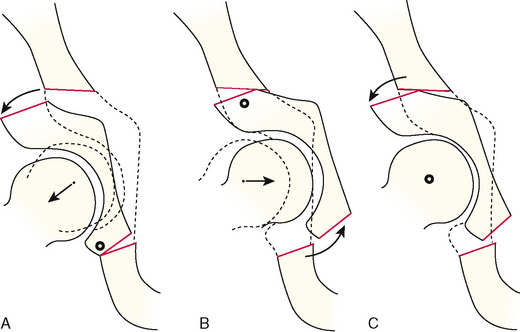

The acetabular fragment is now freely movable and thus can be reoriented. Because there is a tendency of the dysplastic joint to lateralize, the fragment must be correspondingly medialized. If the center of rotation is in a proper position, the correction is achieved by rotating the acetabular fragment around the femoral head. A supra-acetabular gap that appears during correction is always the result of hinging caused by incomplete posterocaudal mobilization or a persisting bone bridge (Figure 26-8). The correction depends on the area of deficient cover. The preoperative assessment of the anteroposterior pelvic radiograph includes an analysis of the lateral, anterior, and posterior coverage. Anterolateral deficiency is most commonly present, but one has to be aware that approximately 15% of these hips have a posterior deficiency (i.e., acetabular retroversion). For the most common type, the main correction is an anterior rotation in combination with some internal rotation. In general, this leads to sufficient lateral coverage. The correction is provisionally stabilized with two 2.5-mm threaded Kirschner wires advanced from the iliac crest into the fragment. The checking of the correction is performed with an anteroposterior radiograph of the entire pelvis that permits for a comparison with the opposite hip. The inclination of the weight-bearing area of the acetabulum should not go beyond the horizontal plane. The edges of the anterior and posterior wall should meet at the lateral edge of the sourcil. The center of the femoral head should lie neither too lateral nor too medial as measured by the distance between the medial border of the femoral head and the ilioischiatic line. Novices in particular run the risk of overcorrection, either by exaggerating the lateral coverage or by creating retroversion of the acetabulum. Overcorrection of the acetabulum may lead to a pincer type of femoroacetabular impingement. Even for the experienced surgeon, several adjustments and corresponding radiographs are necessary.

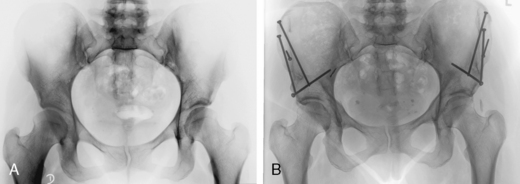

Figure 26-9 shows the preoperative and postoperative radiographs of a patient with bilateral dysplasia.

Technical Pearls

Results and outcomes

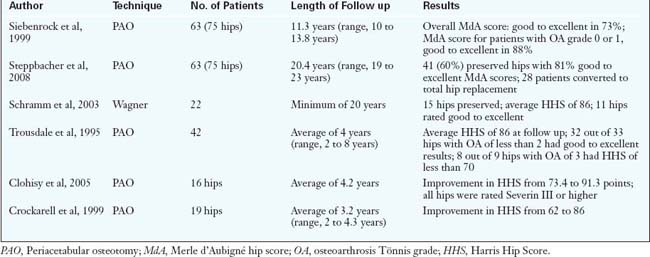

There are several short-term outcomes reported from various centers. The results are remarkably consistent and can be summarized as follows: patients with minimal to moderate arthritic changes usually achieve pain relief and improved function after surgery. However, patients with advanced radiographic degenerative changes have less predictable success (Table 26-1).

Annotated references and suggested readings

Beck M., Leunig M., Ellis T., Sledge J.B., Ganz R. The acetabular blood supply: implications for periacetabular osteotomies. Surg Radiol Anat. 2003;25:361-367.

Carlioz H., Khouri N., Hulin P. Ostéotomie triple juxtacotyloidi- enne. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1982;68:497-501.

Clohisy J.C., Barrett S.E., Gordon J.E., Delgado E.D., Schoenecker P.L. Periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of severe acetabular dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:254-259.

Crockarell J.Jr, Trousdale R.T., Cabanela M.E., Berry D.J. Early experience and results with the periacetabular osteotomy. The Mayo Clinic experience. Clin Orthop. 1999;363:45-53.

Davey J.P., Santore R.F. Complications of periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop. 1999;363:33-37.

Ganz R., Klaue K., Vinh T.S., Mast J.W. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias. Technique and preliminary results. Clin Orthop. 1988;232:26-36.

This is the original description of the technique of periacetabular osteotomy..

Hempfing A., Leunig M., Nötzli H.P., Beck M., Ganz R. Acetabular blood flow during Bernese periacetabular osteotomy: an intraoperative study using laser Doppler flowmetry. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:1145-1150.

Hussel J.G., Rodriguez J.A., Ganz R. Technical complications of the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop. 1999;363:81-92.

LeCoeur P. Corrections des défauts d’orientation de l’articulation coxofemorale par ostéotomie del’isthme iliaque. Rev Chir Orthop. 1965;51:211-212.

Leunig M., Siebenrock K.A., Ganz R. Rationale of periacetabular osteotomy and background work. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83:438-448.

Mast J.W., Brunner R.L., Zebrack J. Recognizing acetabular version in the radiographic presentation of hip dysplasia. Clin Orthop. 2004;418:48-53.

Murphy S., Deshmukh R. Periacetabular osteotomy: preoperative radiographic predictors of outcome. Clin Orthop. 2002;405:168-174.

Myers S.R., Eijer H., Ganz R. Anterior femoroacetabular im-pingement after periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop. 1999;363:93-99.

Reynolds D., Lucas J., Klaue K. Retroversion of the acetabulum. A cause of hip pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81:281-288.

Salter R.B. Innominate osteotomy in the treatment of congenital dislocation and subluxation of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1961;43:518-539.

Schramm M., Hohmann D., Radespiel-Troger M., Pitto R.P. Treatment of the dysplastic acetabulum with Wagner spherical osteotomy. A study of patients followed for a minimum of twenty years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85:808-814.

Siebenrock K.A., Schöll E., Lottenbach M., Ganz R. Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop. 1999;363:9-20.

Steppbacher S.D., Tannast M., Ganz R., Siebenrock K.A. Mean 20-year followup of Bernese periacetabular osteotomy. Clin Orthop. 2008;466:1633-1644.

Tonnis D., Behrens K., Tscharani F. Eine neue Technik der Dreifachosteotomie zur Schwenkung dysplastischer Hiiftpfannen bei Jugendlichen und Erwachsenen. Z Orthop. 1981;119:253-263.

Trousdale R.T., Ekkernkamp A., Ganz R., Wallrichs S.L. Periacetabular and intertrochanteric osteotomy for the treatment of osteoarthrosis in dysplastic hips. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:73-85.