Chapter 10 The ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm

Analysis and Presentation of a New Algorithm*

I Introduction

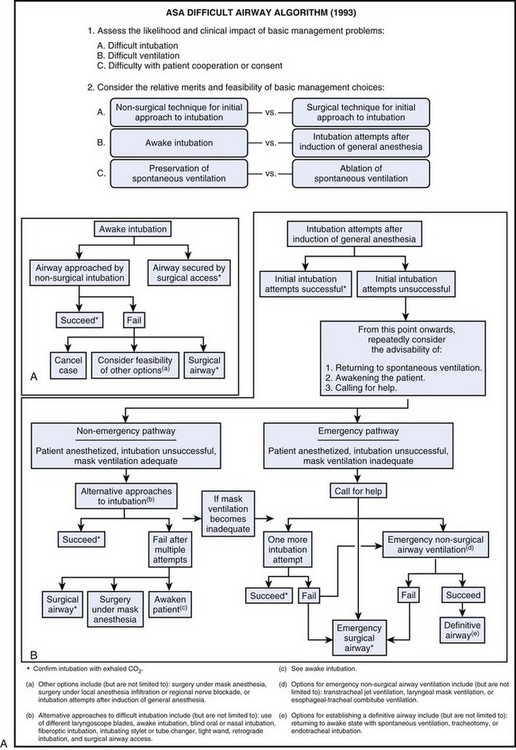

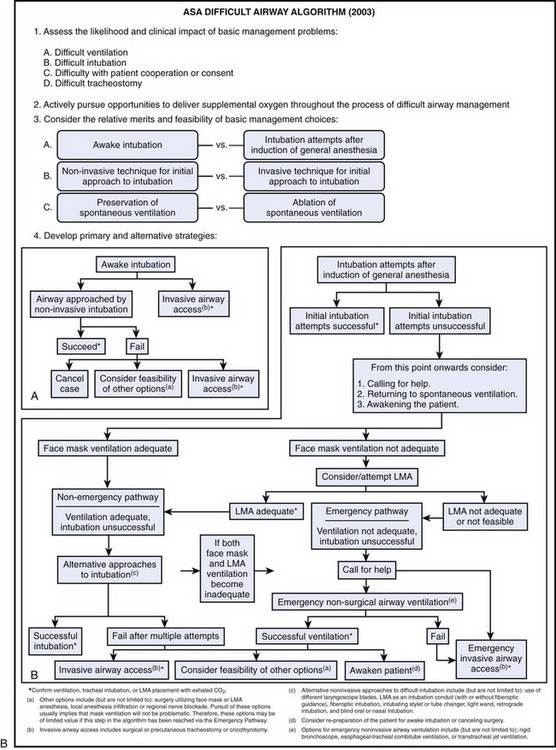

The original ASA DAA was developed over a 2-year period by the ASA Task Force on Guidelines for Management of the Difficult Airway.1 The task force included academicians, private practitioners, airway experts, adult and pediatric anesthesia generalists, and a statistical methodologist. The algorithm was introduced by ASA as a practice guideline in 1993. In 2003, the ASA task force presented a revised algorithm that essentially retained the same concept but recommended a wider range of airway management techniques than was previously included, based on more recent scientific evidence and the advent of new technology.

II the ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm

A side-by-side comparison of the original (1993) and the updated (2003) versions of the ASA DAA is presented in Figure 10-1. The differences between the two algorithms are listed in Box 10-1. Certain aspects of the algorithm require further explanation.

Box 10-1 Differences between 1993 and 2003 ASA Management of the Difficult Airway Algorithms

1. Difficult ventilation is now listed first under item 1, “Assess the Likelihood and Clinical Impact of Basic Management Problems.” Also, in the same category, Difficult tracheostomy was added.

2. A new item 2 was inserted: “Actively pursue opportunities to deliver supplemental oxygen throughout the process of difficult airway management.”

3. When considering the relative merits and feasibility of basic management choices (item 3), awake intubation versus intubation attempts after induction of anesthesia should now be considered first, before noninvasive versus invasive techniques as the initial approach to intubation.

4. Use of the laryngeal mask airway (LMA) was incorporated into the algorithm in the awake induction limb and in both the nonemergency and emergency pathways for induction after general anesthesia (either as a ventilatory device or as a conduit for tracheal intubation).

5. The option for “One more intubation attempt” was removed.

6. Use of the rigid bronchoscope was added as an option for emergency noninvasive ventilation.

A Patient Evaluation and Risk Assessment

The ASA DAA begins with the most basic question of whether or not the presence of a DA is recognized (see Chapter 9). Recognizing the potential for difficulty leads to proper mental and physical preparation and an increased chance of a good outcome. In contrast, failure to recognize this potential results in unexpected difficulty in the absence of proper mental and, likely, physical preparation, with an increased chance for a catastrophic outcome.

Airway evaluation should take into account any characteristics of the patient that could lead to difficulty in the performance of (1) bag-mask or supraglottic airway ventilation, (2) laryngoscopy, (3) intubation, or (4) a surgical airway. Routine patient evaluation can be best structured as follows (see Chapter 9 for details):

1. Obtain an airway history to identify medical, surgical, and anesthetic factors that may indicate the presence of a DA.

2. Evaluate for systemic diseases (e.g., respiratory failure, coronary artery disease) that might place limits on awake intubation, such as increased fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2), or require special attention, such as prevention of sympathetic nervous system stimulation.

3. Examine previous anesthetic records, which can yield useful information about previous airway management.

4. Conduct a physical examination of the airway to detect physical characteristics that might indicate the presence of a DA (Table 10-1):

TABLE 10-1 Components of the Preoperative Airway Physical Examination

| Airway Examination Component | Nonreassuring Findings |

|---|---|

| Length of upper incisors | Relatively long |

| Relation of maxillary and mandibular incisors during normal jaw closure | Prominent “overbite” (maxillary incisors anterior to mandibular incisors) |

| Relation of maxillary and mandibular incisors during voluntary protrusion of the jaw | Patient’s mandibular incisors anterior to (in front of) mandibular incisors |

| Interincisor distance | <3 cm |

| Visibility of uvula | Not visible when tongue is protruded with patient in sitting position (e.g., Mallampati class III or IV) |

| Shape of palate | Highly arched or very narrow |

| Compliance of mandibular space | Stiff, indurated, occupied by mass, or nonresilient |

| Thyromental distance | <3 ordinary finger breadths |

| Length of neck | Short |

| Thickness of neck | Thick |

| Range of motion of head and neck | Patient cannot touch tip of chin to chest or cannot extend neck |

The findings of the airway history and physical examination may be useful in guiding the selection of specific diagnostic tests and consultation to further characterize the likelihood or nature of the anticipated airway difficulty.2

B Difficult Bag-Mask Ventilation

The risk for difficult mask ventilation (DMV) is the first issue addressed in the most recent version of the DAA. Evidence from the literature3 suggests that the incidence of DMV is 5% in the general adult population, that the presence of DMV is associated with difficult intubation, and that DMV is not accurately predicted by anesthesiologists.

Five independent criteria predict DMV (age >55 years, body mass index >26 kg/m2, lack of teeth, presence of mustache or beard, and history of snoring), and the presence of two such risk factors indicates a high likelihood of DMV.3 It is important to keep these risk factors in mind, because some of them can be reversed. For example, DMV may possibly be preventable by shaving a patient’s beard, leaving dentures in place during bag-mask ventilation (BMV), and performing a workup and treating for possible obstructive sleep apnea.

C Awake Tracheal Intubation

Awake intubation is generally more time-consuming for the anesthesiologist and a more unpleasant experience for the patient. However, if a difficult intubation is anticipated, awake endotracheal intubation is indicated for three reasons: (1) the natural airway is better maintained in most patients when they are awake (i.e., “no bridges are burned”); (2) the orientation of upper airway structures is easier to identify in the awake patient (i.e., muscle tone is maintained to keep the base of the tongue, vallecula, epiglottis, larynx, esophagus, and posterior pharyngeal wall separated from one another)4,5; and (3) the larynx moves to a more anterior position with the induction of anesthesia and paralysis, which makes conventional intubation more difficult.6

Crucial to the success of endotracheal intubation while the patient is awake is proper preparation (see Chapter 11 for further details). Most intubation techniques work well in patients who are cooperative and whose larynx is nonreactive to physical stimuli. In general, the components of proper preparation for an awake intubation are the following:

• Psychological preparation (awake intubation proceeds more easily when the patient knows and agrees with what is going to happen)

• Appropriate monitoring (i.e., electrocardiography, noninvasive blood pressure monitoring, pulse oximetry, and capnography)

• Oxygen supplementation (e.g., nasal prongs, nasal cannula, suction channel of a fiberoptic bronchoscope [FOB], transtracheal catheter)7–10

• Vasoconstriction of the nasal mucous membranes (if performing nasal intubation)

• Administration of a drying agent

• Judicious sedation (keeping the patient in meaningful contact with the environment)

• Adequate airway topicalization (consider performance of bilateral laryngeal nerve blocks, blocking the lingual branch of the glossopharyngeal nerve and the superior laryngeal nerve)

Box 10-2 lists the suggested ASA guidelines for contents of a portable airway management cart.11

Box 10-2 Suggested Contents of the Portable Storage Unit for Difficult Airway Management

1. Rigid laryngoscope blades of alternative design and size from those routinely used; may include a rigid fiberoptic laryngoscope

2. Endotracheal tubes of assorted sizes

3. Endotracheal tube guides, such as semirigid stylets, ventilating tube changer, light wands, and forceps designed to manipulate the distal portion of the endotracheal tube

4. Laryngeal mask airways (LMAs) of assorted sizes; may include the Fastrach intubation LMA and the ProSeal LMA (LMA North America, San Diego, CA).

5. Fiberoptic intubation equipment

6. Retrograde intubation equipment

7. At least one device suitable for emergency nonsurgical airway ventilation, such as the esophageal-tracheal Combitube (Tyco Healthcare, Mansfield, MA), a hollow jet ventilation stylet, and a transtracheal jet ventilator

8. Equipment suitable for emergency surgical airway access (e.g., cricothyrotomy)

There are numerous methods to intubate the trachea or ventilate a patient (see Part Four of this text). Box 10-3 shows a list of the techniques contained within the ASA guidelines. The techniques chosen depend, in part, on the anticipated surgery, the condition of the patient, and the skills and preferences of the anesthesiologist. Based on recent evidence from the literature12–14 considerations should also include the use of video laryngoscopy, despite the fact that this technique is not mentioned in the recent ASA algorithm, but likely will be included in future revisions of the guidelines.

• Surgery may be canceled (e.g., the patient needs further counseling, airway edema or trauma has resulted, different equipment or personnel is necessary).

• General anesthesia may be induced (the fundamental problem must be considered to be a lack of cooperation, and mask ventilation must be considered nonproblematic).

• Regional anesthesia may be considered (careful clinical judgment is required to balance risks and benefits; see Chapter 45).

• A surgical airway may be created (if the surgery is essential and general anesthesia is considered to be inappropriate until intubation is accomplished); this may be the best choice to secure the airway in patients with laryngeal or tracheal fracture or disruption, upper airway abscess, or combined mandibular-maxillary fractures.

D Difficult Intubation in the Unconscious or Anesthetized Patient

All of the intubation techniques that are described for the awake patient1,15 can be used in the unconscious or anesthetized patient without modification. However, direct laryngoscopy and fiberoptic laryngoscopy are likely to be more difficult in the paralyzed, anesthetized patient compared with the awake patient, because the larynx may move to a more anterior position, relative to other structures, as a result of relaxation of oral and pharyngeal muscles.6 In addition and more importantly, orientation may be impaired because the upper airway structures can coalesce into a horizontal plane instead of separating out in a vertical plane.4,5

In the anesthetized patient whose trachea has proved difficult to intubate even with a video laryngoscope it is necessary to try to maintain gas exchange between intubation attempts (by mask ventilation) and, whenever possible, during intubation attempts through the use of (1) supplemental oxygen11; (2) positive-pressure ventilation via an anesthesia mask that incorporates a self-sealing diaphragm for entry of the FOB airway intubator (instead of the standard oropharyngeal airway)5,16; or (3) a laryngeal mask airway (LMA; LMA North America, Inc., San Diego, CA) as a conduit for the FOB (see Chapters 19 and 22).17

One must not continue with the same technique that did not work before. The amount of laryngeal edema and bleeding is likely to increase after every intubation attempt, particularly with the use of a laryngoscope or retraction blade. The most common scenario in the respiratory catastrophes in the ASA closed claims study was the development of progressive difficulty in ventilating by mask between persistent and prolonged failed intubation attempts. The final result was inability to ventilate by mask and provide gas exchange (see Chapter 55).18

For each additional attempt, consider modifications, such as improved sniffing position, external laryngeal manipulation, a new blade or new technique, or involvement of a much more experienced laryngoscopist. However, the number of intubation attempts should be limited and the following options should be considered: (1) awaken the patient and do the procedure another day; (2) continue anesthesia by mask or LMA ventilation; (3) perform a surgical airway (tracheostomy or cricothyrotomy) before the ability to ventilate the lungs by mask is lost (see Fig. 10-1).

• Immediately apply Trendelenburg position.

• Turn the head, and perhaps the body, to the left.

• Suction the mouth and pharynx with a large-bore suction device.

• Try endotracheal intubation while the patient is in the lateral position (the tongue may be more out of the way, but this position is unfamiliar to most anesthesiologists).

• If the endotracheal tube (ETT) has been passed into the esophagus, it may be left there; this may allow decompression of the stomach, and it identifies the esophagus during subsequent intubation attempts (the disadvantage is that it interferes with satisfactory mask seal).

• After securing the airway, consider tracheal suctioning, mechanical ventilation, positive end-expiratory pressure, fiberoptically guided saline lavage, steroids, antibiotics (see Chapter 35).

E The “Cannot Intubate, Cannot Ventilate” Scenario

The development of the LMA was a major advance in the management of difficult intubation and difficult ventilation scenarios. The LMA is suggested as a ventilation device or a conduit for a flexible FOB,19,20 and the Fastrach intubating LMA (ILMA) may also be utilized.10,17,21 The LMA and the Combitube are supraglottic ventilatory devices and are not helpful if the airway obstruction is located at or below the glottic opening.22 Use of the rigid bronchoscope may be required to establish a patent airway because it allows ventilation even past an obstruction at these levels. If immediately available, TTJV is relatively easy to perform and can be life-saving.23 However, it carries significant risks such as subcutaneous emphysema (if the upper airway is not patent or the catheter is not entirely tracheal) and barotrauma (too forced ventilation or proximal airway obstruction)24 The techniques mentioned can provide time until definitive airway management by tracheal intubation (via direct, fiberoptic, or retrograde technique) or by formal tracheostomy can be performed.25,26 Future research will determine the role of the new rigid video laryngoscopes in the rescue of the “cannot intubate, cannot ventilate” scenario.

Ultimately, a cricothyrotomy may be necessary, but fewer than 50% of anesthesiologists feel competent to perform one.27 Nevertheless, when one is faced with a failed airway, preparations for a surgical airway must begin immediately, and once the decision is made, it is essential to use an effective technique (see Chapters 30 and 31). Despite limited familiarity with the procedure, the risks of an invasive rescue technique must be weighed against the risks of hypoxic brain injury or death.28

F Extubation of a Patient with a Difficult Airway

• Awake extubation versus extubation before return of consciousness

• Clinical symptoms with the potential to impair ventilation (e.g., altered mental status, abnormal gas exchange, airway edema, inability to clear secretions, inadequate return of neuromuscular functions)

• Airway management plan if the patient is not able to maintain adequate ventilation

• Short-term use of a ventilating tube exchanger (TE) or jet stylet (can be used for ventilation and guided reintubation)

The ideal method of extubation of a patient with a DA is gradual, step by step, and reversible at any time. Extubation over a ventilating TE or jet stylet closely approximates this ideal.16 The equipment that should be immediately available for the extubation of a DA includes that necessary for intubation of the DA (see Chapter 50).29

G Follow-up Care of a Patient with a Difficult Airway

• Description of the airway difficulties, which should distinguish between difficulties with mask ventilation and those with tracheal intubation

• Description of the airway management techniques used, which should indicate the beneficial or detrimental role of each technique in management of the DA

• Information given the patient (or responsible person) concerning the airway difficulty that was encountered. The intent of this communication is to assist the patient (or responsible person) in guiding and facilitating the delivery of future care. The information conveyed may include, for instance, the presence of a DA, the apparent reasons for the difficulty, and implications for future care.

The provider should also strongly consider dispensing or advising a Medic-Alert bracelet for the patient (see Chapter 54). Finally, the anesthesiologist should evaluate and observe the patient for potential complications of DA management, such as airway edema, bleeding, tracheal or esophageal perforation, pneumothorax, and aspiration.

III Summary of the ASA Algorithm

After several unsuccessful attempts at intubation, it may be best to awaken the patient; administer regional anesthesia, if appropriate (see Chapter 45); proceed with the case using mask or LMA ventilation; or perform a semielective tracheostomy. If the ability to ventilate by mask is lost and the patient’s lungs cannot be ventilated, LMA ventilation should be instituted immediately. If LMA ventilation does not provide adequate gas exchange, either TTJV or a surgical airway should be instituted immediately.

Four concepts emerge from the preceding discussion— four very important, take-home messages on the ASA DAA. These are presented in Box 10-4.

IV Problems with the ASA Algorithm and Likely Future Directions

The strength of the ASA DAA is twofold. First, it is very thorough and complete with respect to the options available when an anesthesiologist encounters a DA. Second, it emphasizes the need for and importance of an organized approach to airway management.30

• Although it is intended to apply to all patients of all ages, there are certain populations of patients in which further considerations are necessary. Examples include pediatric patients (see Chapter 36), obstetric patients (see Chapter 37), nonfasted patients, and patients with obstruction at or below the level of the vocal cords.31

• The algorithm’s clinical end point is successful intubation, but endotracheal intubation may not be necessary, and successful ventilation may suffice.

• The algorithm is fairly complex, allowing a wide choice of techniques at each stage, and its multiplicity of pathways may limit its clinical usefulness in guiding day-to-day practice.32 Unlike the algorithm used in advanced life support (ACLS) guidelines, for example, the ASA DAA is not binary in nature.33

• Somewhat vague terminology is used in its definitions of difficult tracheal intubation and difficult laryngoscopy. Definitions of optimal-best attempts at conventional laryngoscopy, mask ventilation, and difficult laryngoscopy or intubation are important because they provide an end point at which the practitioner should stop using a particular approach (limiting risk) and move on to something that has a better chance of working (gaining benefit).

• The algorithm mentions ablation of spontaneous ventilation with muscle relaxants but does not discuss the great clinical management implications of muscle relaxants that have different durations of action.

• Although the algorithm advises confirmation of endotracheal intubation, the usefulness of capnography for this purpose is limited during cardiac arrest, which is not an uncommon consequence of the CICV scenario; the esophageal detector device is not similarly limited (see Chapter 32).

• The algorithm does not provide a definitive flow chart for extubation of the DA that incorporates the use of a device that can serve as a guide for expedited reintubation or ventilation, if necessary.

• The role of regional anesthesia in patients with a DA requires further clarification (see Chapter 45).

• The algorithm does not include the use of rigid video laryngoscopy which has dramatically changed the day-to-day clinical practice in recent years and has been shown to be able to rescue failed direct laryngoscopy, particularly in the DA.12,13

A Terminology in the ASA Difficult Airway Algorithm

The original publications that introduced the ASA algorithm and provided basic terms that define a DA were relatively vague in their terminology1:

• Difficult mask ventilation: “It is not possible for the anesthesiologist to provide adequate face mask ventilation due to one or more of the following problems: inadequate mask seal, excessive gas leak or excessive resistance to the ingress or egress of gas.”

• Difficult laryngoscopy: “Not being able to visualize any portion of the vocal cords after multiple attempts at conventional laryngoscopy.”

• Difficult intubation: “When tracheal intubation requires multiple attempts in the presence or absence of tracheal pathology.”

• Failed intubation: “Placement of the tracheal tube fails after multiple intubation attempts” (0.05% of surgical patients and 0.13% to 0.35% in obstetric patients).

B Definition of Optimal-Best Attempt at Conventional Laryngoscopy

An optimal-best attempt at conventional laryngoscopy is defined as having the following characteristics34,35:

1. Performed by a reasonably proficient anesthesiologist with at least 3 years of experience (Rationale: If such an experienced anesthesiologist is having difficulty in visualizing the glottis, no other anesthesiologist or surgeon needs to or should attempt the same maneuver)

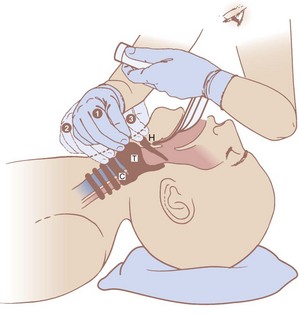

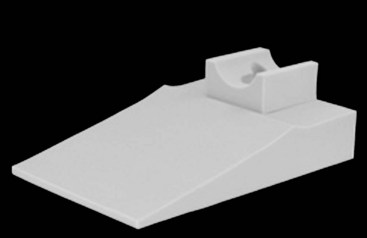

2. With the patient in the optimal “sniffing” position (Rationale: No attempt is wasted because the position was suboptimal; slight flexion of the neck on the head and severe extension of the head on the neck aligns the oral, pharyngeal, and laryngeal axes into a straight line; positioning devices are necessary in the obese patient [Fig. 10-2])

3. Using the appropriate type and length of blade (Rationale: Macintosh-type blades work best in patients with little upper airway room, and Miller-type blades are ideal for patients who have small mandibular space, anterior larynx, large incisors, or a long, floppy epiglottis). Based on most recent literature, a rigid video laryngoscope should be considered at least for the second attempt, if immediately available.

4. Using the appropriate blade length (Rationale: Patients’ airways vary in size, and optimal fit of the blade to the airway allows the best possible pressure application to lift the epiglottis directly or indirectly)

5. Having a low threshold for using optimal external laryngeal manipulation (OELM) or backward upward rightward pressure (BURP) (Fig. 10-3) (Rationale: Both maneuvers can frequently improve the laryngoscopic view by at least one entire grade and should be an inherent part of laryngoscopy and an instinctive reflex response to a poor laryngoscopic view)

Figure 10-2 Troop Elevation Pillow with additional foam head rest.

(Courtesy of Mercury Medical, Clearwater, FL.)

C Definition of Optimal-Best Attempt at Conventional Mask Ventilation

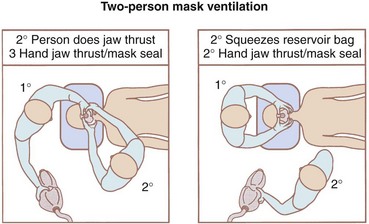

An optimal-best attempt at conventional mask ventilation is defined as having the following characteristics34,35:

1. Performed by a reasonably proficient anesthesiologist with at least 3 years of experience (Rationale: as above)

2. With the patient in the optimal sniffing position (Rationale: as above)

3. Using two-person BMV with the most proficient anesthesiologist holding the mask and the less proficient anesthesiologist squeezing the bag (Fig. 10-4) (Rationale: Usually this leads to a far better mask seal, better jaw thrust, and therefore higher tidal volume than can be achieved with one person in a difficult-to-mask patient)

4. Using appropriately sized oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airway devices that have been inserted correctly (Rationale: This provides a canal for airflow through the soft tissue of the upper airway; establishes and improves tidal volume)

If mask ventilation is very poor or nonexistent, even with a vigorous two-person effort in the presence of large artificial airways, this constitutes a classic CICV scenario, and the team needs to start potentially life-saving plan B (see Fig. 10-1).

D Options for the CICV Scenario

Both the LMA and the Combitube have been shown to work well to rescue airway emergencies.17,36,37 The ASA DAA does not dictate the order of preference of these devices in the CICV situation, but the following considerations must be taken into account: (1) the anesthesiologist’s own experience and level of comfort in the use of these methods, (2) the availability of these devices, (3) the type of airway obstruction (upper versus lower), and (4) the benefits and risks involved.

The ProSeal LMA usually forms a better seal than the LMA-Classic and provides improved protection against aspiration.38–48 When properly positioned, the Combitube allows ventilation with a higher seal pressure than the LMA-Classic, protects against regurgitation,49 and allows further attempts at intubation while the esophageal cuff protects the airway.50 The Combitube has been successfully used in difficult intubation and CICV situations,49,51–55 including ventilation failure with an LMA.56

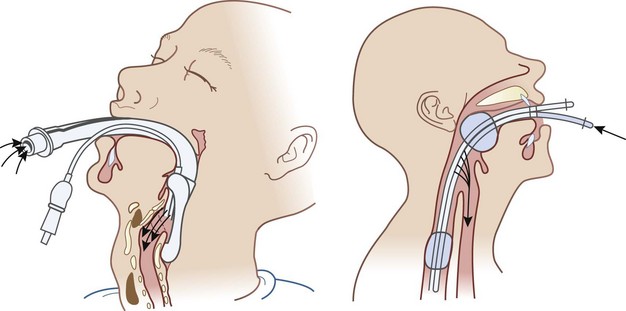

Both the LMA and the Combitube are supraglottic ventilatory devices (Fig. 10-5). They cannot solve a truly glottic problem (e.g., spasm, massive edema, tumor, abscess) or a subglottic problem.37 If an obstacle is suspected to exist in the glottic or subglottic area, the ventilatory mechanism (e.g., ETT, TTJV, rigid ventilating bronchoscope, surgical airway) needs to be positioned below the level of the lesion. The ASA DAA does not discriminate between the obstructed and the unobstructed airway, and this is a critical weakness of the algorithm.

E Determinants of the Use of Muscle Relaxants for Difficult Airway Management

Muscle relaxants have different characteristics regarding time of onset and duration that significantly determine their advantages and disadvantages in the context of airway management (Table 10-2). The key elements in the choice of a nondepolarizing muscle relaxant are whether mask ventilation will be adequate and what rescue plan has been determined. For instance, with the induction of general anesthesia in an uncooperative patient who has a DA, the anesthesiologist should consider the relative merits of preservation of spontaneous ventilation versus use of muscle relaxants. Alternatively, if a small dose of succinylcholine (0.5 to 0.75 mg/kg) is used, good intubating conditions can be achieved within 75 seconds for about 60 seconds, allowing an early-awaken option if the ETT cannot be placed. In contrast, use of succinylcholine during DA management may not be the best choice if mask ventilation is considered possible and the alternative plan of action is FOB.5

TABLE 10-2 Advantages and Disadvantages of Muscle Relaxants with Different Durations of Action

| Muscle Relaxant | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Succinylcholine | Permits the awaken option at the earliest time possible | A period of poor ventilation (spontaneous or with positive pressure) may occur as the drug wears off Does not permit a smooth transition to plan B (e.g., use of a fiberoptic bronchoscope) and so on |

| Nondepolarizing | Permits a smooth transition to plan B and so on, provided mask ventilation is adequate | Does not allow awaken option at an early time |

Moreover, endotracheal intubation can be successfully accomplished without the use of any muscle relaxant, and this option should be considered in certain situations.57,58 Another consideration is that in most patients, prior administration of a small dose of a nondepolarizing neuromuscular blocker may slightly diminish the duration of action of succinylcholine,59 and therefore the time to spontaneous recovery of airway reflexes may be shortened.

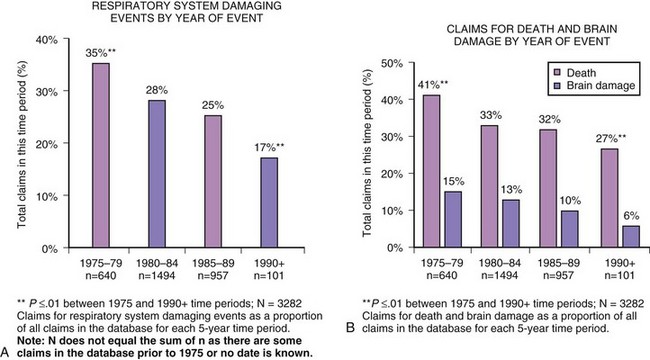

F Summary

In summary, the ASA DAA has worked well over the past decade. In fact, there has been a very dramatic decrease (30% to 40%) in the number of respiratory-related malpractice lawsuits, brain damage, and deaths attributable to anesthesia since 1990 (Fig. 10-6).60 However, a number of issues have emerged that indicate that the algorithm can be improved, as discussed earlier. Consideration of these issues should make the algorithm still more clinically specific and functional. Nonetheless, the DAA provides excellent guidelines for anesthesiologists in their clinical decision-making for patients with DAs. Successful management in these cases is key to reducing the risk of anesthesia-related morbidity and mortality.

V Introduction of A New comprehensive Airway Algorithm

Most recently we incorporated the use of video laryngoscopy into the new comprehensive airway algorithm based on new evidence that strongly supports its role either as primary device or as first rescue device during the management of a difficult airway.12,13

• Subalgorithm A = cannot ventilate, cannot intubate (CICV)

• Subalgorithm B = can ventilate but cannot intubate via laryngoscopy

• Subalgorithm C = ventilation established through a subglottic airway, further management options

• Subalgorithm D = surgical airway management

• Subalgorithm E = extubation of a patient with a known or suspected DA

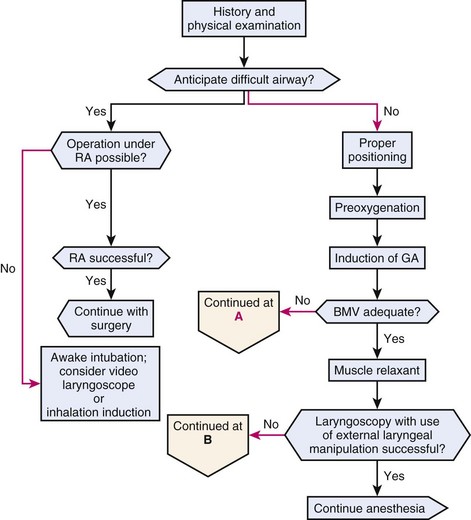

A The Main Algorithm

This algorithm (Fig. 10-7) is intended for and limited to elective surgery in the operating room and does not include airway trauma and crash intubations. As with the ASA algorithm, the crux of management of the DA lies in its recognition (Box 10-5). If difficulties are anticipated, surgery under regional anesthesia may be considered. However, there are anesthetic, surgical, and patient factors that may render the option of regional anesthesia for surgery inappropriate (Box 10-6). If regional anesthesia is considered appropriate and successful anesthesia is achieved, then surgery may proceed. However, if regional anesthesia fails, then the option for an awake airway technique or inhalation induction should be considered. Similarly, if regional anesthesia is not an appropriate option for surgery, then the performance of an awake intubation or inhalation induction is recommended.

Box 10-5 Individual Predictors of Difficult Airway Management*

Box 10-6 Factors Influencing the Choice of Regional Anesthesia (RA) in Patients with a Difficult Airway (DA)

Patient

Failure of an awake technique usually falls into three categories: oversedation, obscuration of vision (by blood or secretions), and technical difficulties. If the patient is oversedated, airway issues may become complicated. If optimal attempts at BMV are successful, then Pathway B may be followed. However, if optimal attempts at BMV fail, the anesthesiologist should quickly proceed to Pathway A. If difficulty occurs with any of the awake fiberoptic techniques as a result of blood, mucus, or secretions such that adequate visualization is not possible, a blind technique may be considered (see “Bloody Airways.”) Additionally, more invasive techniques, such as a surgical airway or retrograde intubation may be performed.

2 New Algorithm Pathways

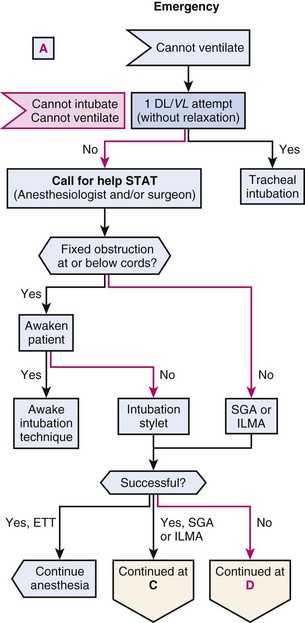

a Pathway A

The CICV scenario is an emergency situation in which the optimal-best attempt at ventilation and intubation has failed (Fig. 10-8). If muscle relaxants have not been administered, then one further laryngoscopy attempt, preferably using a video laryngoscope if available, or a conventional direct laryngoscope.12,13 without muscle relaxation can be made (preferably by another experienced anesthesiologist). If tracheal intubation fails, assistance should be summoned. Thereafter, the algorithm alerts the anesthesiologist to the difference in airway management with respect to the possibility of a fixed obstruction (e.g., tumor, vocal cord paralysis) at or below the cords.

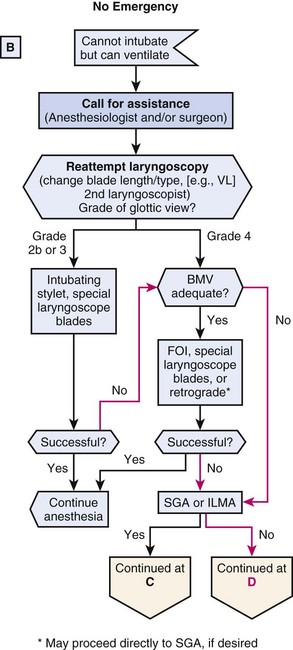

b Pathway B

Pathway B (Fig. 10-9) is derived from a situation where oxygenation and ventilation are adequate but a definitive airway has not been established. After calling for assistance and repeating laryngoscopy, using a video laryngoscope, if available, the management is divided based on the grade of glottic view. If a Cormack-Lehane grade 2B or 3 laryngoscopic view is visualized, an intubating stylet, or special laryngoscopic blade or video laryngoscope can be helpful. If this is successful, surgery may proceed. However, if the attempt is not successful, then adequacy of BMV must be reassessed, especially if BMV has not been attempted previously (i.e., rapid-sequence induction). If BMV is adequate, then further elective measures may be considered. If a grade 4 laryngoscopic view is observed, a retrograde technique may be considered or the anesthesiologist may proceed directly to SGA or ILMA, depending on the availability of equipment and the expertise of the anesthesiologist. However, if BMV is inadequate, then it is likely inappropriate to perform a fiberoptic intubation (FOI) or retrograde intubation. Instead, the anesthesiologist should recognize this as an emergent situation and immediately attempt SGA or ILMA.

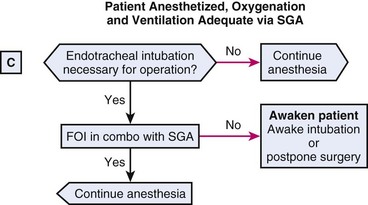

c Pathway C

Pathway C (Fig. 10-10) represents a situation in which the patient is anesthetized and oxygenation and ventilation are adequate via an SGA. The decision to intubate depends on the answer to the question, “Is endotracheal intubation necessary for the surgical procedure?” If the answer is “No,” surgery may continue with an SGA. If the answer is “Yes,” FOI through the SGA with an Aintree Intubation Catheter (Cook Critical Care, Bloomington, IN) may be performed. Alternatively, if an ILMA or CTrach (LMA International, Singapore) was inserted as the SGA, intubation via these devices is appropriate. However, if intubation attempts fail, it would be appropriate to awaken the patient and perform an awake intubation.

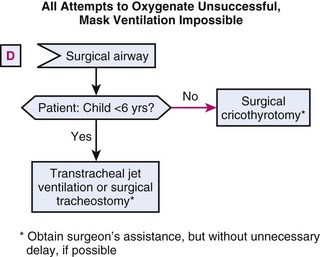

d Pathway D

In Pathway D (Fig. 10-11), all attempts to oxygenate and ventilate the patient have been unsuccessful. A surgical airway is crucial, and in patients older than 6 years of age, the cricothyroid membrane (CTM) remains the window to the airway. However, if the patient is younger than 6 years old, the CTM is not well developed, and TTJV or the performance of a surgical tracheostomy is advised.

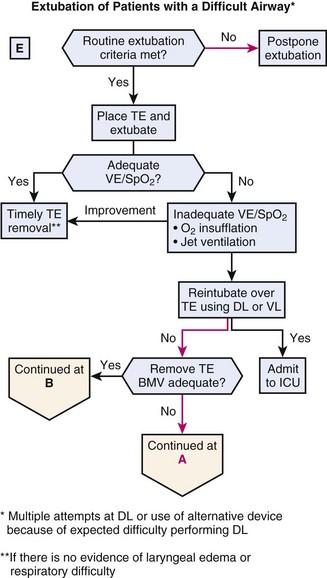

e Pathway E

After a secure airway has been established, there will come a time when extubation is necessary. Consultants of the ASA Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway,5 as well as the Canadian Airway Focus Group, recommended a preformulated strategy for extubation of the DA.61 Extubation strategies are discussed in detail in Chapter 50. Extubation strategies for the DA include, but are not limited to, bronchoscopic examination under general anesthesia through an SGA, substitution of an ETT with an SGA, and extubation over a TE.

Pathway E (Fig. 10-12) is an extubation algorithm in which a TE used is for patients who underwent multiple attempts at direct laryngoscopy or for whom alternative rescue devices were used. It should also be used for patients with a known or suspected DA who have undergone successful intubation. If the patient has met the extubation criteria (Box 10-7), one of the aforementioned extubation strategies can be used. A TE may be placed and the ETT removed over it, leaving the TE in the trachea. If ventilatory parameters and oxygenation are adequate, the TE can then be removed, provided there is no evidence of laryngeal edema or respiratory difficulty. The length of time for which these catheters are left in place is most commonly 30 to 60 minutes, although durations as long as 72 hours have been reported in the literature. Clinical judgment should be used according to the particular situation.

VII Clinical Pearls

• There is strong evidence demonstrating that successful airway management in the perioperative environment depends on the specific strategies used. The purpose of the American Society of Anesthesiologists Algorithm on the Management of the Difficult Airway (ASA DAA) is to facilitate management of the difficult airway (DA) and to reduce the likelihood of adverse outcomes.

• We are presenting a new comprehensive airway management algorithm that is organized like the BLS/ACLS algorithms in a binary fashion and eliminates some of the weaknesses of the ASA DAA.

• Based on most recent evidence, video laryngoscopy emerges as a superior alternative for primary management of the difficult airway and as an excellent rescue device for failed DL in such circumstance.

• Recognizing the potential for difficulty leads to proper mental and physical preparation and increases the chance of a good outcome.

• Airway evaluation should take into account any characteristics of the patient that could lead to difficulty in the performance of (1) bag-mask or supraglottic airway ventilation, (2) laryngoscopy, (3) intubation, or (4) a surgical airway.

• In the anesthetized patient whose trachea has proved to be difficult to intubate, it is necessary to try to maintain gas exchange by mask ventilation between intubation attempts and also during intubation attempts, whenever possible.

• The most common scenario in the respiratory catastrophes reported in the ASA closed claims study was the development of progressive difficulty in ventilating by mask between persistent and prolonged failed intubation attempts; the final result was inability to ventilate by mask or to provide gas exchange.

• The Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA) and the Combitube are supraglottic ventilatory devices and are not helpful if the airway obstruction is located at or below the glottic opening.

• Extubation of the patient with a DA should be carefully assessed and performed, and the anesthesiologist should develop a strategy for safe extubation of these patients (depending on the type of surgery, the condition of the patient, and the skills and preferences of the anesthesiologist).

• The presence and nature of the airway difficulty should be documented in the medical record.

• If blood appears in the airway as a result of awake or asleep intubation techniques, direct visualization through a fiberoptic bronchoscope may be technically challenging. In such situations, a blind technique may be more useful.

• Although no airway algorithm can be practiced in its entirety on a regular basis, anesthesiologists need to incorporate alternative devices and techniques into their daily practice so that they can develop the confidence and skill required for their successful use in the emergent setting.

All references can be found online at expertconsult.com.

1 American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: A report. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:597–602.

2 Hagberg CA, Ghatge S. Does the airway examination predict difficult intubation? In: Fleisher L, ed. Evidence-based practice of anesthesiology. Philadelphia: Elsevier Science; 2004:34–46.

3 Langeron O, Masoo E, Huraux C, et al. Prediction of difficult mask ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1229–1236.

5 Practice Guidelines for the Management of the Difficult Airway. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on the Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1269–1277.

10 Mark L, Foley L, Michelson J. Effective dissemination of critical airway information: The Medical Alert National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry. Hagberg CA, ed. Airway management: Principles and practice, ed 2, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2007.

17 Benumof JL. Laryngeal mask airway: Indications and contraindications. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:843–846.

18 Caplan RA, Posner KL, Ward RJ, et al. Adverse respiratory events in anesthesia: A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:828–833.

27 Ezri T, Szmuk P, Warters RD, et al. Difficult airway management practice patterns among anesthesiologists practicing in the United States: Have we made any progress? J Clin Anesth. 2003;15:418–422.

32 Heidegger T, Gerig HJ, Ulrich B, et al. Validation of a simple algorithm for tracheal intubation: Daily practice is the key to success in emergencies—An analysis of 13,248 intubations. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:517–522.

60 Cheney FW. Committee on Professional Liability: Overview. ASA Newsletter. 1994;58:7–10.

1 American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Management of the Difficult Airway. Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: A report. Anesthesiology. 1993;78:597–602.

2 Hagberg CA, Ghatge S. Does the airway examination predict difficult intubation? In: Fleisher L, ed. Evidence-based practice of anesthesiology. Philadelphia: Elsevier Science; 2004:34–46.

3 Langeron O, Masoo E, Huraux C, et al. Prediction of difficult mask ventilation. Anesthesiology. 2000;92:1229–1236.

4 Fink RB. Respiration, the human larynx: A functional study. New York: Raven Press; 1975.

5 Practice Guidelines for the Management of the Difficult Airway. An updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on the Management of the Difficult Airway. Anesthesiology. 2003;98:1269–1277.

6 Rogers S, Benumof JL. New and easy fiberoptic endoscopy aided tracheal intubation. Anesthesiology. 1983;59:569–572.

7 Baraka A. Transtracheal jet ventilation during fiberoptic intubation under general anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1986;65:1091–1092.

8 Benumof JL, Scheller MS. The importance of transtracheal jet ventilation in the management of the difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 1989;71:769–778.

9 Dallen L, Wine R, Benumof JL. Spontaneous ventilation via transtracheal large bore intravenous catheter is possible. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:531–533.

10 Mark L, Foley L, Michelson J. Effective dissemination of critical airway information: The Medical Alert National Difficult Airway/Intubation Registry. Hagberg CA, ed. Airway management: Principles and practice, ed 2, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2007.

11 Penmant JH, Walker MB. Comparison of the endotracheal tube and laryngeal mask airway in airway management by paramedical personnel. Anesth Analg. 1992;74:531–534.

12 Aziz MF, Healy D, Kheterpal S, et al. Routine clinical practice effectiveness of the Glidescope in difficult airway management: an analysis of 2,004 Glidescope intubations, complications, and failures from two institutions. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:34–41.

13 Aziz MF, Dillman D, Fu R, Brambrink AM. Comparative effectiveness of the C-MAC video laryngoscope versus direct laryngoscopy in the setting of the predicted difficult airway. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:629–636.

14 Kaplan MB, Hagberg CA, Ward DS, et al. Comparison of direct and video-assisted views of the larynx during routine intubation. J Clin Anesth. 2006;18:357–362.

15 Benumof JL. Management of the difficult airway: With special emphasis on awake tracheal intubation. Anesthesiology. 1991;75:1087–1110.

16 Miller KA, Harkin CP, Bailey PL. Postoperative tracheal extubation. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:149–172.

17 Benumof JL. Laryngeal mask airway: Indications and contraindications. Anesthesiology. 1992;77:843–846.

18 Caplan RA, Posner KL, Ward RJ, et al. Adverse respiratory events in anesthesia: A closed claims analysis. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:828–833.

19 Benumof JL. The laryngeal mask airway and the ASA difficult airway algorithm. Anesthesiology. 1996;84:686–699.

20 Patil V, Stehling LC, Zauder HL, et al. Mechanical aids for a fiberoptic endoscopy. Anesthesiology. 1982;57:69–70.

21 Brain AI, Verghese C, Addy EV, et al. The intubating laryngeal mask. I: Development of a new device for intubation of the trachea. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79:699–703.

22 Henderson JJ, Popat MT, Pearce AC. Difficult Airway Society guidelines for management of the unanticipated difficult intubation. Anaesthesia. 2004;59:675–694.

23 Weymuller EA, Parlin EG, Paugh D, et al. Management of the difficult airway problems with percutaneous transtracheal ventilation. Ann Otol Rhinol Largyngol. 1987;96:34–37.

24 Urtubia RM, Aguila CM, Cumsille MA. Combitube: A study for proper use. Anesth Analg. 2000;90:958–962.

25 Ala-Kokko TI, Kyllonen M, Nuutinen L. Management of upper airway obstruction using a Seldinger minitracheotomy kit. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1996;40:385–388.

26 Johnson C. Fiberoptic intubation prevents a tracheostomy in a trauma victim. AANA J. 1993;61:347–348.

27 Ezri T, Szmuk P, Warters RD, et al. Difficult airway management practice patterns among anesthesiologists practicing in the United States: Have we made any progress? J Clin Anesth. 2003;15:418–422.

28 Salem R, Baraka A. Confirmation of tracheal intubation. Hagberg CA, ed. Airway management: Principles and practice, ed 2, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2007.

29 Mercer M. Respiratory failure after tracheal extubation in a patient with halo frame cervical spine immobilization rescue therapy using the Combitube airway. Br J Anaesth. 2001;86:886–891.

30 Larson CP. A safe, effective, reliable modification of the ASA difficult airway algorithm for adult patients. Curr Rev Clin Anesth. 2002;23:1–12.

31 Davies JM, Weeks S, Crone LA, et al. Difficult intubation in the parturient. Can J Anaesth. 1989;36:668–674.

32 Heidegger T, Gerig HJ, Ulrich B, et al. Validation of a simple algorithm for tracheal intubation: Daily practice is the key to success in emergencies—An analysis of 13,248 intubations. Anesth Analg. 2001;92:517–522.

33 Channing L, Cummins RO. ACLS Provider Manual. Dallas: American Heart Association; 2000.

34 Benumof JL. Difficult laryngoscopy: Obtaining the best view. Can J Anaesth. 1994;41:361–365.

35 Benumof JL, Cooper SD. Quantitative improvement in laryngoscopic view by optimal external laryngeal manipulation. J Clin Anesth. 1996;8:136–140.

36 Brain AIJ, Ferson DZ. Laryngeal mask airway. Hagberg CA, ed. Airway management: Principles and practice, ed 2, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2007.

37 Frass M, Urtubia R, Hagberg C. The Combitube. Hagberg CA, ed. Airway management: Principles and practice, ed 2, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2007.

38 Brain AI, Verghese C, Strube PJ. The LMA “ProSeal”: A laryngeal mask with an oesophageal vent. Br J Anaesth. 2000;84:650–654.

39 Brimacombe J, Keller C. The ProSeal laryngeal mask airway: A randomized, crossover study with the standard laryngeal mask airway in paralyzed, anesthetized patients. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:104–109.

40 Brimacombe J, Keller C, Brimacombe L. A comparison of the laryngeal mask airway ProSeal and the laryngeal tube airway in paralyzed anesthetized adult patients undergoing pressure-controlled ventilation. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:770–776.

41 Brimacombe J, Keller C, Fullekrug B, et al. A multicenter study comparing the ProSeal and Classic laryngeal mask airway in anesthetized, nonparalyzed patients. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:289–295.

42 Cook TM, Nolan JP, Verghese C, et al. Randomized crossover comparison of the ProSeal with the Classic laryngeal mask airway in unparalysed anaesthetized patients. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:527–533.

43 Keller C, Brimacombe J. Mucosal pressure and oropharyngeal leak pressure with the ProSeal versus laryngeal mask airway in anaesthetized paralysed patients. Br J Anaesth. 2000;85:262–266.

44 Lu PP, Brimacombe J, Yang C, et al. ProSeal versus the Classic laryngeal mask airway for positive pressure ventilation during laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:824–827.

45 Brimacombe J, Keller C. Airway protection with the ProSeal laryngeal mask airway. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2001;29:288–291.

46 Evans NR, Gardner SV, James MF. ProSeal laryngeal mask protects against aspiration of fluid in the pharynx. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:584–587.

47 Evans NR, Llewellyn RL, Gardner SV, et al. Aspiration prevented by the ProSeal laryngeal mask airway: A case report. Can J Anaesth. 2002;49:413–416.

48 Keller C, Brimacombe J, Kleinsasser A, et al. Does the ProSeal laryngeal mask airway prevent aspiration of regurgitated fluid? Anesth Analg. 2000;91:1017–1020.

49 Baraka A, Salem R. The Combitube oesophageal-tracheal double lumen airway for difficult intubation. Can J Anaesth. 1993;40:1222–1223.

50 Tighe SQM. Failed tracheal intubation. Anaesthesia. 1992;47:356.

51 Banyai M, Falger S, Roggla M, et al. Emergency intubation with the Combitube in a grossly obese patient with bull neck. Resuscitation. 1993;26:271–276.

52 Bigenzahn W, Pesau B, Frass M. Emergency ventilation using the Combitube in cases of difficult intubation. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1991;248:129–131.

53 Eichinger S, Schreiber W, Heinz T, et al. Airway management in a case of neck impalement: Use of the oesophageal tracheal Combitube airway. Br J Anaesth. 1992;68:534–535.

54 Klauser R, Roggla G, Pidlich J, et al. Massive upper airway bleeding after thrombolytic therapy: Successful airway management with the Combitube. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:431–433.

55 Sivarajan M, Fink BR. The position and the state of the larynx during general anesthesia and muscle paralysis. Anesthesiology. 1990;72:439–442.

56 McLellan I, Gordon P, Khawaja S, et al. Percutaneous transtracheal high frequency jet ventilation as an aid to difficult intubation. Can J Anaesth. 1988;35:404–405.

57 Walts P, Smith I. Clinical studies of the interaction between d-tubocurarine and succinylcholine. Anesthesiology. 1969;31:39–44.

58 Wong AKH, Teco GS. Intubation without muscle relaxant: An alternative technique for rapid tracheal intubation. Anesth Intensive Care. 1996;24:224–230.

59 Tunstall ME, Geddes C. “Failed intubation” in obstetric anaesthesia: An indication for use of the “Esophageal Gastric Tube Airway. Br J Anaesth. 1984;56:659–661.

60 Cheney FW. Committee on Professional Liability: Overview. ASA Newsletter. 1994;58:7–10.

61 Crosby ET, Cooper PM, Douglat MJ, et al. The unanticipated difficult airway with recommendations for management. Can J Anaesth. 1998;45:757–776.

* Parts of this chapter are adapted and modified from a previous publication on a similar topic: Hagberg C, Lam N, Brambrink AM: Current concepts in airway management in the operating room: A new approach to the management of both complicated and uncomplicated airways. Curr Rev Clin Anesth 28:73–88, 2007.