Chapter 28 The anaesthetist and the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency

All products, except medicines, used in health care for the diagnosis, prevention, monitoring, treatment or alleviation of illness or handicap are medical devices. There are thus about half a million items falling under the jurisdiction of the MHRA. While some, such as syringes, ventilators and tracheal tubes, are in routine use by anaesthetists, many other medical devices (e.g. artificial eyes, condoms and surgical supports) have little impact on our professional life. Unregulated manufacture and use of medical devices, much like unregulated medical practitioners, have the capacity to inflict great harm, both on patients and on those operating the device (Fig. 28.1).

A glossary of terms used in regulation of medical devices is given in Appendix 1.

Standards

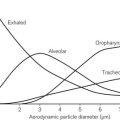

Health-care professionals are by no means the first group to recognize and demand the need for consistent, universal standards in the equipment and materials they work with; in other industries this process dates back many years. An essential requirement for mass distribution of goods is certifiable manufacturing specifications. Industrial standards grew less from a need for safety and more for reasons of commerce, but the potential to advance safe manufacture and use of equipment was soon exploited. During the early industrial revolution, widely used items were custom-built by many manufacturers. The chaos this caused, when trying to put different components together, led to the birth of the standard setting body. The first of these, the British Standards Institute (BSI), began work in 1901 specifying dimensions of rails and steel plate, and now encompasses a wide range of standards from heavy engineering to good employment practice. Attempts at international standardization commenced soon after in the electrotechnical field and culminated ultimately in the establishment of a new body: the International Organization for Standardization based in Geneva, which started work in 1947 (in the spirit of standardization, the abbreviation ISO is retained across all languages). The ISO will be familiar to many anaesthetists as the body that resolved the seemingly random sizes of breathing system connectors (Fig. 28.2) into the universal system we have today (Fig. 28.3).

Figure 28.2 A selection of connectors from older breathing systems showing the lack of uniform dimensions. (Compare with Fig. 28.3.)

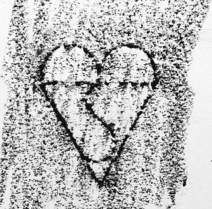

These organizations produce the standards, but do not enforce them: in the majority of cases the application of standards is voluntary. Organizations can, however, provide independent inspection of products covered by a standard: a process termed conformity assessment. In the UK, BSI also has a conformity assessment function as well as being a standards body. Where BSI carries out such an assessment and a product meets the appropriate standards, the manufacturer may be entitled to affix the familiar BSI Kitemark to its product as a sign of manufacturing conformity (Fig. 28.4).

Figure 28.4 British conformity assessment: a reproduction of the BSI Kitemark taken from a drain cover.

The ISO has also published generic standards for quality management systems. This is the ISO 9000 family of standards (ISO 9001, ISO 9002, ISO 9003). Manufacturers and many other organizations and businesses may choose, as a marker of quality, to be certified by an independent organization as meeting the requirements of the appropriate ISO 9000 standard. This should not be confused with conformity assessment of the finished product.

CE marking

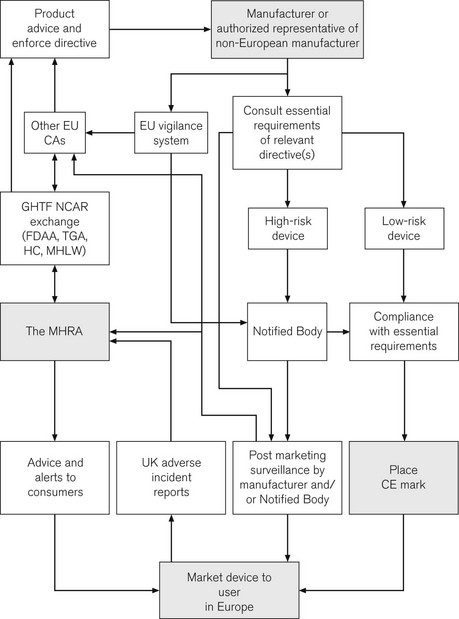

As the EU expands and integrates, there is a need for harmonized conformity assessment of the many goods passing across the borders of member states. Items deemed to require this are described in a number of directives; all medical devices are encompassed within three directives. Within each directive, essential requirements specify the standards for each item. A manufacturer confirms compliance with the essential requirements of a directive by placing the CE (Conformité Européene) mark on their product, once they have followed and complied with an appropriate conformity assessment route (Fig. 28.5). There are certain exceptions from CE marking for ‘custom made’ and investigational devices. Apart from these exceptions, any item specified within a directive cannot be sold within the EU without a CE mark. Regardless of which member state authorizes the manufacturer to place the mark, the item can be marketed in all member states, thus marking achieves both product regulation and compliance with the EC single market. It is inherent in the regulations that products imported from outside the EU are subject to the same set of rules.

Competent authorities and notified bodies

CE marking is of great importance to the health-care sector. Following the incorporation of the Medical Devices Directives, it is now a legal requirement for all medical devices purchased for use in the UK to have a CE mark. A major role for the MHRA is to oversee this process; it is, therefore, termed the Competent Authority for the UK, with other European countries having similar organizations. Exchange of information between Competent Authorities ensures a common approach throughout Europe. Hence, in essence, the MHRA is the UK arm of a large pan-European organization responsible for regulating medical devices. The directives and the standards within are produced by mutual agreement of EU member states, possibly incorporating standards from organizations such as the BSI or ISO (see above). The manufacturer is ultimately responsible for placing the mark and verifying that their product meets essential requirements. For simple low-risk items, the manufacturer can directly place the CE mark. More complex devices, such as pacemakers, require detailed independent verification and certification by an independent organization, termed a Notified Body, who then issue certification to allow the placing of the CE mark. A flow chart illustrates how the system works and where the MHRA may be involved (Fig. 28.6).

The implications of this whole process, for the anaesthetist in particular, and for those involved in producing and modifying medical devices, are discussed in greater detail elsewhere.1 Although recently passed into UK law, it may only be a short time before a CE mark is detectable on every piece of medical equipment in UK hospitals. CE marks are of course not limited to medical devices; other directives stipulate a wide range of marketed products from detonators to jet skis, though not pedalos!

Limitations of CE marking

To the end user, the CE mark implies that the product is made to a Europe-wide standard; is compliant with the regulations; its manufacturer can be traced and is liable for the product within the terms of its prescribed use, and in correct use the benefits should far outweigh any risks. Medical devices placed on the market in the UK are regulated by the MHRA. It will investigate whether essential requirements are met, that UK Notified Bodies are suitably qualified, and, rarely, it may take action against manufacturers who fail to comply with the directive. Despite offering this reassurance, the Medical Devices Directive is not perfect and modification is needed in some areas. Devices may need to be re-classified to a higher-risk group needing more intensive pre-marketing testing, or essential requirements can need to be redrafted to reflect problems discovered in use.

Essential requirements determine whether a device is fit for purpose and may focus on tissue compatibility, decontamination and similarity in design to existing devices rather than clinical efficacy of the device when in use. The implications of this for the paediatric anaesthetist have been discussed in Chapter 12. This situation is also illustrated by anaesthetic breathing system filters. Produced to the same essential requirements, and appropriately CE marked, filters from different manufacturers show wide variation in performance when subject to more intensive testing which may translate to variation in performance in clinical use. The MHRA reported an independent investigation of the performance of breathing system filters, allowing practitioners a more informed choice of which product they wish to use.2 Another example of varying clinical performance by similarly marked products is the group of supraglottic airway devices (see Chapter 6, Supraglottic airway devices). Again, they bear the appropriate CE mark, but may lack adequate clinical testing prior to market release, with some devices performing inadequately.3 According to the directive, complaints from users which reach the manufacturer should be recorded, together with action taken. Ultimately, this should ensure design refinement and improved performance. Whether this system is sufficiently robust is uncertain. An alternative is for the anaesthetic community to develop improved clinical testing of products, driven by centrally coordinated, peer reviewed publication of clinical evaluation. The debate goes on. 4,5

Global harmonization

The lack of universal consent in health care can be startling. Manufacturers cannot agree the simplest things: the best colour to paint oxygen cylinders (ISO R 32/BSS 1319, first published in 1955, specified colours for medical gas cylinders – the fact that the standards have not been internationally adopted illustrates the voluntary nature of standards), and nor can we agree how to diagnose death.6

UK consumer advisory role

The wider role of the MHRA on the European and international scene has a direct impact on the working life of the anaesthetist. Work by the National Audit Office in 1999 on equipment purchase and maintenance in the UK revealed deficiencies and inconsistent practice. The MHRA has issued comprehensive guidance documents7,8 to address this. Other bodies also provide advice for anaesthetists responsible for purchasing, maintaining and using medical devices within the UK and Ireland.9 National audit has been initiated under the auspices of the Controls Assurance Support Unit (CASU) to whom trusts are obliged to provide regular audit returns, based on details within the MHRA recommendations.

Adverse incident reportage

• other competent authorities in the EU

• through the obligatory vigilance system followed by manufacturers

Medical device-related adverse incidents are also reported to other bodies, such as the National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA). Data provided to the NPSA are sourced from anonymous critical incident reporting and analyzed to detect trends and identify areas to improve practice. Unfortunately, such overlap between authorities can be counter-productive; for example, NPSA data cannot be traced to source, and thus faulty equipment reports cannot be explored further with the reporter. Ideally, all medical device-related adverse incidents should be reported to the MHRA primarily and then additionally to other authorities as and when it is thought necessary: it may be insufficient to depend on channels of communication between organizations after the report is received. Electronic reporting by all parties is encouraged; the Manufacturers’ On-line Reporting Environment (MORE) enables rapid communication of alerts from companies. Adverse incident reports are investigated according to the level of risk and incident frequency. The investigation may lead to design changes and/or improved advice to users.

Safety advice

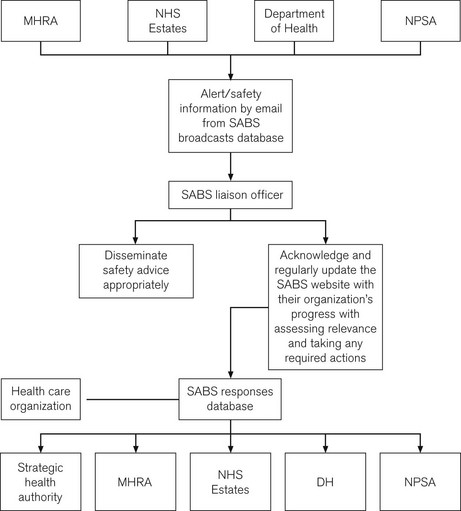

Since 2004, a new system, the Safety Alert Broadcast System (SABS), sends out alerts by e-mail and requires a liaison officer to send confirmation of receipt and subsequent action. SABS may also contain alerts from the NPSA, NHS Estates and patient safety specific guidance from the Department of Health (Fig. 28.7). The advice contained within safety alerts is not enforceable, but should be viewed as reflecting best practice. As such, a decision not to heed all or part of a warning may require a robust defence.

Trusts must have in place a system ensuring appropriate and timely dissemination of alerts and are obliged to take action by the deadlines dictated in the alert; failure to do this and to ensure that subsequent practice does not regress may result in repetition of harmful incidents and unnecessary injury.10 With increasing complexity of medical devices, particularly in the electrotechnical field, sudden failure remains a risk no matter how robust the design. In reporting such incidents, the importance of maintaining an intuitive manual back-up system is continually emphasized.11

Other MHRA publications

Annual adverse incident report

• Healthcare establishment/user responsibility: ‘after delivery’ – e.g. performance and/or maintenance failures and device degradation

• Manufacturer responsibility; ‘before delivery’ – design, manufacture, quality control and packaging

• No established device/use link – where the device was subsequently found to work as intended (possibly due to an intermittent fault, tampering or user error) or the device was not available for inspection.

For example, in 2008 (reported in DB2009(02)), there were 8902 incidents reported to the MHRA and of these 2.4% involved a fatality and 13.4% a serious injury.12 The categories of ‘healthcare establishment/user responsibility’ and ‘no established device/use link’ (which is likely to be unascribed user error) accounted for 70% of causes. It bears repetition to state here that user error, especially when commonplace, is likely to be a consequence of poor design (see Chapter 29, Error, Man and Machine) or poor instructions for use and on its own does not absolve the MHRA or manufacturers of the need for further examination of the device. If reported, these will be investigated in the same way as a defect in the device itself.

The anaesthetist’s role

The main aim of incident reporting is to identify the potential for harm before actual harm occurs. The importance of prompt reporting and prompt action on device alerts is self-evident. Health-care workers in the UK are encouraged to report any device failure to the MHRA who aim to recognize patterns of problems or particularly serious isolated issues worthy of action. There is a natural tendency to under-report adverse incidents, particularly when the practitioner perceives some element of personal responsibility. This undermines the value of a system that is not seeking to apportion blame, but to learn from such problems and to direct manufacturers or practitioners in such a way that safe use of all devices is maximized. Reports can be communicated to the MHRA on-line, by e-mail, telephone, fax or post (see Appendix 2).

The reader may wonder whether anaesthetists feature with greater frequency in reports of equipment misuse and failure than other specialists. Certainly anaesthetists work in a device rich environment, but are generally well-trained and examined in the correct function and application of a wide range of equipment and are aware of the consequences of device failure or abuse. Just occasionally items neither directly connected to administration of anaesthesia nor operated by an anaesthetist can present us with a major problem.13 Continued vigilance is required from us and from our colleagues, to provide the information necessary to alert others to potential hazard from an increasingly complex array of medical equipment. The application of safety and conformity marks to an item does not mean it is incapable of being dangerous given incorrect use or unanticipated malfunction (Fig. 28.8). The MHRA provides an invaluable resource, aiming to promote the safe and effective use of medical devices within the UK and beyond.

Appendix 1

Glossary

Adverse Incident: An event that causes, or has the potential to cause, unexpected or unwanted effects involving the safety of patients, users or other persons.

Authorized Representative: A body within the EU appointed by a manufacturer from outside the EU to enable them to meet the requirements of conformity assessment.

BSI: The British Standards Institute, the oldest such organization in the world responsible for a wide range of standards, they are also a recognized Notified Body.

CASU: The Controls Assurance Support Unit, soon to become the Healthcare Standards Unit, this body implements controls assurance and maintains and evaluates new health care standards.

CE mark: (Conformité Européene) confirms compliance with product directive standards for the EU; the size and form in which the mark appears are closely specified in Council Decision 93/465/EC.

CEN: (Comité Européen de Normalisation) European Committee for Standardization. One of three standards organizations for the EU with CENELEC (electro-technical) and ETSI (telecommunications), they develop European standards and consider applications for standards.

CNST: The Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts provides guidance and incentive for trusts to improve their risk management and insures them against claims for damages arising from clinical negligence.

Committee on Safety of Devices: Set up to complement the work of the MHRA by advising ministers and overseeing strategic direction in improving medical device safety and the work of the MHRA.

Competent Authority: A national organization overseeing the Medical Devices Directive; the MHRA is the Competent Authority for the UK.

Conformity Assessment: Testing of a product or process and certification that it meets a particular set of standards, usually confirmed by placing a mark somewhere on that product.

EGBAT: The Expert Group on Blocked Anaesthetic Tubing, a UK body set up to investigate the reasons for these untoward incidents and to suggest how they may be prevented.

Essential Requirements: Those agreed standards specified within a directive that a product must meet to gain a CE mark.

GHTF: The Global Harmonization Task Force, a multinational body currently chaired by the EU, which aims to harmonize features of medical devices on a worldwide scale.

ISO: International Organization for Standardization, founded in 1947, determines a wide range of international standards.

Liaison Officer: Person within a health-care organization responsible for receiving alerts from and communicating with the MHRA, it is anticipated that most liaison officers will take on the role of SABS liaison officer.

NAO: The National Audit Office is the non-governmental auditor of public spending.

Notified Body: An institution recognized by the Competent Authority of that state for the purposes of carrying out CE conformity assessment procedures.

NPSA: The National Patient Safety Agency is a special health authority created by the Department of Health as part of its drive to produce ‘an organization with memory’, to report and learn from problems affecting patient safety.

Patient Safety Research Programme: Undertake to research the safety of practice in certain areas; for example, a current programme is examining the risks of reuse of single-use products.

SABS: The Safety Alert Broadcast System, an initiative by the MHRA employing electronic communication to improve the flow of information for safety alerts.

Standards: Documented voluntary agreements which establish important criteria for products, services and processes. For a standard to be European, it must be adopted by one of the European standards organizations and made public.

Appendix 2

Adverse incident reporting

Advice on reporting adverse incidents with medical devices is updated and re-issued annually. The latest version can be found on the MHRA website: www.mhra.gov.uk

Enquiries and reporting: 020 3080 7080 (answering machine message has a number for out of hours urgent reports and enquiries)

Forms for reporting specific or general problems are available on the website above.

1 Grant LJ. Regulations and safety in medical equipment design [editorial]. Anaesthesia. 1998;53:1–3.

2 MHRA 04005. Breathing system filters: an assessment of 104 breathing system filters. London: Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency; 2004.

3 Cook TM. Novel airway devices: spoilt for choice? [editorial]. Anaesthesia. 2003;58:107–110.

4 Wilkes AR, Hodzovic I, Latto IP. Introducing new anaesthetic equipment into clinical practice [editorial]. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:571–575.

5 Freeman M, Cooke H. Introducing new anaesthetic equipement into clinical practice [letter]. Anaesthesia. 2009;64:93.

6 Park GR. Death and its diagnosis. Br J Anaesth. 2004;92:625–628.

7 Medicine and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Device bulletin. Managing medical devices, DB2006(05), London, Department of Health, 2006.

8 Medicine and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Devices in practice – a guide for health and social care professionals. London: Department of Health; 2008.

9 Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. Safe management of anaesthetic related equipment. AAGBI Safety Guideline. London: AAGBI; 2009.

10 Carter JA. Checking anaesthetic equipment and the Expert Group on Blocked Anaesthetic Tubing (EGBAT). Anaesthesia. 2004;59:105–107.

11 Medical Device Agency. Medical Device Alert: GE Healthcare Anaesthetic CareStations, (MDA/2009/026), London, Medical Device Agency, 2009.

12 Medicine and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency. Device bulletin. Adverse Incident Reports 2008, DB2009(02), London, Department of Health, 2009.

13 Chawla AV, Newton NI. Machine and monitoring failure from electrical overloading. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:1134–1135.