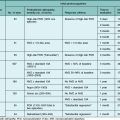

Chapter 100 Techniques of Scleral Buckling

![]() For additional online content visit http://www.expertconsult.com

For additional online content visit http://www.expertconsult.com

Introduction

While almost any rhegmatogenous detachment can be managed with scleral buckling, there has been a trend towards increased use of pneumatic retinopexy and primary vitrectomy.1 This chapter describes the techniques used in scleral buckling. The choice between buckling and other techniques is covered in Chapter 105, Optimal procedures for retinal detachment repair.

The term “buckle” refers to deformation of a structure under stress. Sometimes the term “buckle” is used synonymously with some form of encircling explant, while others use the term to describe local explants.2 In this chapter, the term is used in the more generic sense to imply any type of explant.

Different schools of buckling technique have arisen with divergent views in particular on the role of encirclement and subretinal fluid drainage.3 This chapter has been written to reflect this diversity of practice.

Buckling of the sclera to close retinal breaks was initially achieved using combinations of lamellar scleral dissection with compression sutures until it was shown that it could be achieved more efficiently using scleral implants4 and subsequently explants.5,6 Scleral implants are now of purely historical interest. Likewise diathermy, which was used extensively in the past to achieve retinopexy,4 has been supplanted by photocoagulation and cryotherapy. There have also been subsequent refinements of the basic technique of scleral buckling, including intraocular gas injection and subretinal fluid drainage. However, in contrast with other areas of vitreoretinal surgery, there have been no major innovations in the basic technique of scleral buckling in the past 20 years.

Surgical anatomy

Coats of the eye

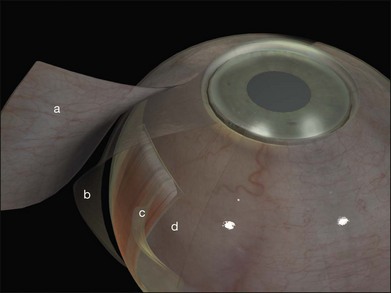

Tenon’s capsule is a layer of fascia that envelops the globe from the limbus to the optic nerve (Fig. 100.1). It is pierced by the extraocular muscles. A glove-like sleeve of fascia extends anteriorly (to the rectus insertions) and posteriorly (for several mm) along the muscles from the points at which they pierce Tenon’s capsule. Between the rectus muscles anteriorly these sleeves are joined by a layer of fascia: the intermuscular septum. The intermuscular septum and fascial sleeves of the recti are sometimes collectively referred to as the posterior Tenon’s capsule. The result of this complex arrangement is that several layers of tissue have to be incised to get access to the surface of the sclera (or sub-Tenon’s space). The anterior Tenon’s capsule may be dissected away from the sclera along with the conjunctiva (to which it is adherent by small fascial filaments). The intermuscular septum is then divided separately. Care must be taken when stripping fascia off the rectus muscles because ligaments from the recti to the wall of the orbit are functionally important in the actions of the muscle.7

Extraocular muscles

The recti are adherent to the sclera at the spiral of Tillaux. The location of this ring corresponds approximately to that of the ora serrata (Fig. 100.2).8 Circumferential scleral tires are therefore often placed as anteriorly as the rectus muscle insertions will allow. In this position they support the retina as far anteriorly as the ora serrata (“break ora occlusive buckling”).

Choroidal vasculature

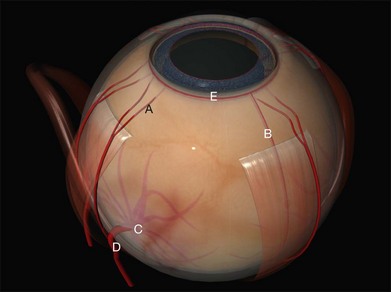

The long posterior arteries (as well as their corresponding nerves) run anteriorly from the equator at 3 and 9 o’clock and may be damaged by heavy photocoagulation or subretinal fluid drainage in these meridia (Fig. 100.3, available online).

The anterior ciliary arteries are useful indicators of the meridia of the rectus muscle insertions (Fig. 100.4). As they supply the arterial circles of the iris surgical trauma (including diathermy) should be minimized.

Preoperative assessment

• Features suggesting that the retinal detachment is nonrhegmatogenous (see also Chapter 96, Nonrhegmatatogenous retinal detachment)

• The presence of vitreous detachment

• Significant ocular co-pathology, which may affect management (e.g., glaucomatous optic neuropathy, aphakia with vitreous in the anterior chamber, a history of strabismus surgery)

Finding the retinal break

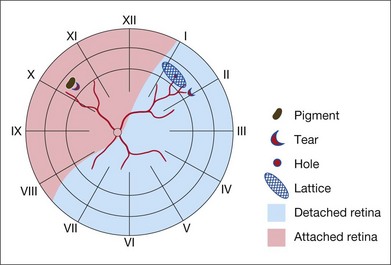

Missed retinal breaks are an important cause of surgical failure so the preoperative examination should be very thorough.9 Even when a break has been found, it is essential to complete examination of the retina, as most retinal detachments have more than one break.10 Their location is carefully documented on a chart that can be referred to subsequently during surgery (Fig. 100.5). These drawings should show the location of retinal breaks in relation to easily visible retinal landmarks such as small hemorrhages, vascular bifurcations, and areas of pigmentation.

Lincoff’s rules

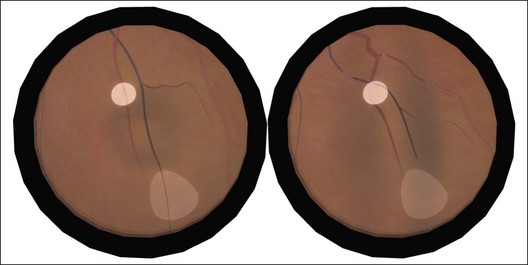

Lincoff has shown how the location of retinal breaks determines the distribution of subretinal fluid (Fig. 100.6).11 Review of the retinal drawings will therefore determine whether the break location is consistent with the subretinal fluid distribution. When the distribution of fluid does not seem to obey Lincoff’s rules reexamine the retina to ensure that no breaks have been missed.

Scheduling surgery

Reducing eye and head movements seems to reduce the rate at which subretinal fluid accumulates. Bed rest, eye patching and rectus sutures have all been used to reduce the amount of subretinal fluid. This may prevent extension of subretinal fluid to the macula and make it easier to identify retinal breaks. It may also avoid the need for subretinal fluid drainage.12 Such measures are rarely practical now, as most retinal detachment care takes place in an ambulatory or semi-ambulatory setting.13

Preparation for surgery

Anesthesia

In theory, sub-Tenon’s anesthesia alone should be insufficient (see above). In practice, sub-Tenon’s anesthesia gives anesthesia equivalent to other techniques,14 presumably due to overspill of anesthetic agents to the peribulbar space. A particular advantage of sub-Tenon’s anesthesia is the ease with which it can be “topped up” intraoperatively.15 Sub-Tenon’s anesthesia may also be a useful adjunct to general anesthesia16 both to block the vagus (preventing bradycardia or asystole from rectus muscle traction) and for analgesia in the immediate postoperative period. The presence of buckles and scarring may make this technique more difficult and less effective in reoperations.

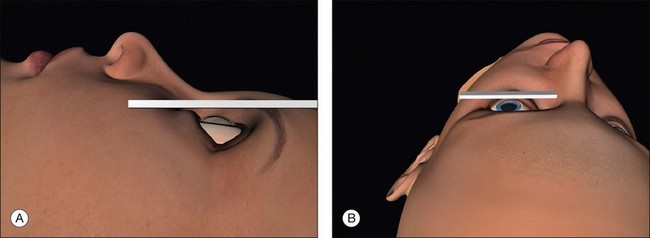

Positioning the head for surgery

Surgical access is best when the orbital rim is horizontal. This is achieved by extending the neck slightly and tilting the nose away from the operated eye (Fig. 100.7, available online). Once in the correct position the head may be fixed with a loop of clinical adhesive tape.

Surgical steps

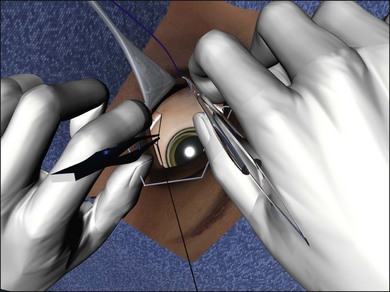

Conjunctival peritomy

A circumferential limbal peritomy with radial relieving incisions is made.17 The conjunctiva 3–4 mm behind the limbus is grasped with forceps and gently lifted creating a radial pleat of conjunctiva (Fig. 100.8). A blunt-tipped spring scissors is used to make a vertical radial cut. A second cut is often needed to extend the incision through Tenon’s capsule down to the sclera. Great care is taken not to tear the conjunctiva. The spring scissors can easily be used in either hand and the orientation varied as the incision progresses. A gentle spreading action of the scissors under the conjunctiva breaks the weak trabecular adhesions to the episcleral tissue.

A slight modification of this technique with the circumferential incision 2 mm behind the limbus leaves a frill that may be useful during closure (Fig. 100.9).

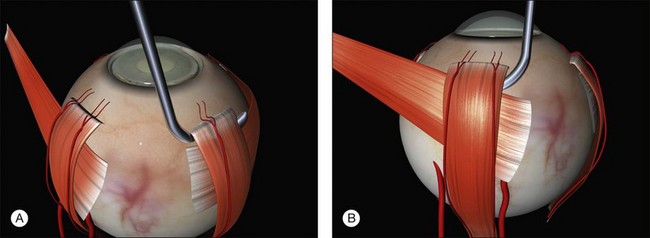

Slinging rectus muscles

Between two and four rectus muscles are slung depending on the planned size of the buckle.

A closed pair of blunt scissors is pushed though the intermuscular septum between two recti. The opening created is enlarged by spreading the blades (Fig. 100.10). In this way, the sub-Tenon’s space is opened and bare posterior sclera is exposed.

The muscle is engaged with a sweeping posterior and circumferential movement around the globe employing a specialized muscle hook (Fig. 100.11, available online). Very posterior “sweeps” risk damage to the vortex veins. Once a rectus has been successfully hooked the globe moves with the hook. If the muscle is inadvertently split a second hook can be passed from the opposite side of the muscle. The remaining anterior fibers of the intermuscular septum are now cut off or swept off. This dissection should be limited to the fascia required to visualize the sclera.

A large braided (e.g., 2/0 silk) bridle suture is passed under the muscle. There are various ways of achieving this involving reverse passage of the suture under the muscle (to avoid engaging the tip in the sclera). Alternatively, a modified muscle hook with a threading eyelet at its tip can be used.18 These bridle sutures can be clipped to the surgical drape to position and stabilize the globe thereafter (e.g., while suturing). When free movement of the globe is desirable (e.g., when searching for breaks) the clips are released.

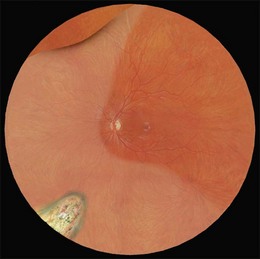

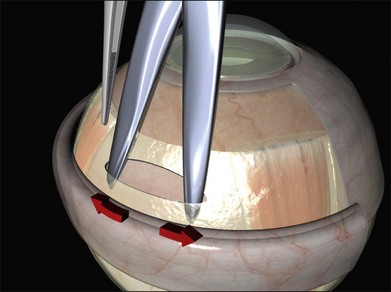

The sclera is now inspected for dark ectatic areas (Fig. 100.12). Suturing and even cryotherapy or indentation at these sites can be perilous so their early identification is essential.

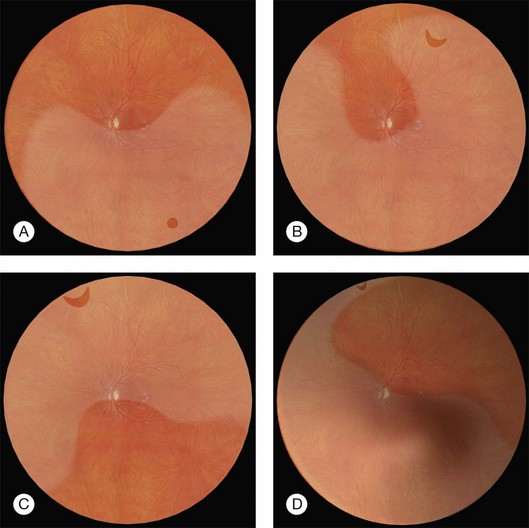

Examination under anesthesia and break localization

The location of each break is marked on the sclera. This essential step is carried out while the cornea is clear and allows planning of the rest of the operation. The sclera is indented under indirect ophthalmoscopic indentation using a fine (but not sharp) tipped instrument such as a Gass scleral indenter.19 Once the indent is seen to correspond to the position of a retinal break sustained (for several seconds) indentation is applied. The resulting transient scleral thinning produces a focal area of scleral translucency and the underlying choroid shows through. This point is then marked with very gentle diathermy or a surgical marker pen. If a marker pen is used the sclera is dried both before and after the application to prevent the dye spreading. Several marks are made for larger breaks.

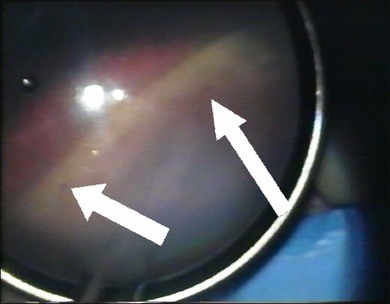

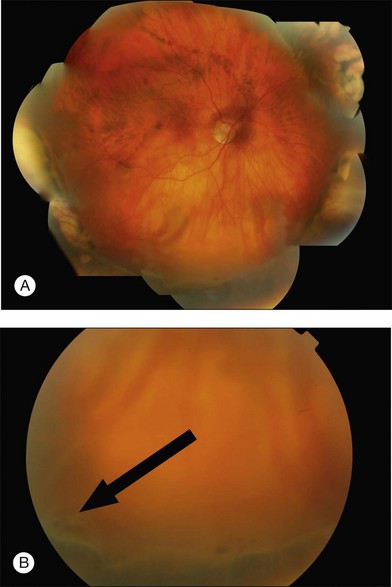

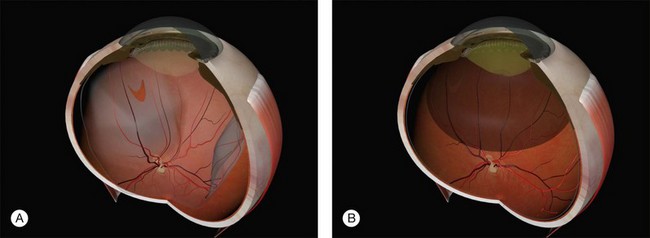

Errors in break localization may lead to buckle malposition. Localization errors tend to be radial (i.e., determining how far back a break is) rather than circumferential (determining its clock hour). For example, if a retinal break is highly elevated (as in a bullous detachment) parallax errors may make the break seem more posterior than it truly is (Fig. 100.13).

Parallax errors may be avoided by draining subretinal fluid and then reforming the globe with air (the DACE operation) (Fig. 100.14).20,21 The view of the retina through the gas bubble can be challenging for those not experienced with this technique.

Retinopexy

The indent from the explant closes retinal breaks but retinopexy is required to produce an enduring bond between the retina and the retinal pigment epithelium that will persist even if the indent disappears.22

Retinopexy was initially achieved using diathermy in association with lamellar scleral dissection and scleral implants.4 Cryotherapy has supplanted diathermy because it can be performed without scleral dissection and the treatment can be monitored ophthalmoscopically. More recently photocoagulation has also been used.

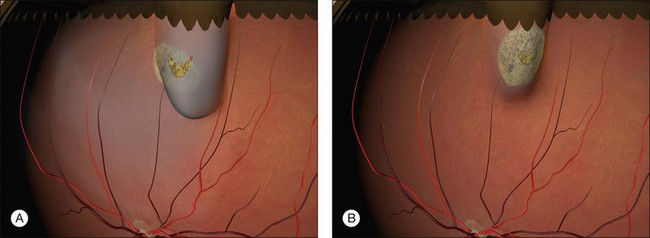

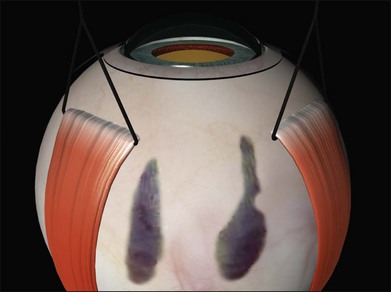

Cryotherapy

The technique of cryotherapy is described in detail in Chapter 106, Prevention of retinal detachment. The aim is to produce freezing of healthy retina surrounding all the retinal breaks. The treatment is monitored using the indirect ophthalmoscope. When the indent from the tip of the cryoprobe is seen under a retinal break the cryoprobe is activated. After a few seconds one observes whitening of the retina. Smaller breaks can be treated with a single application. The break is seen as a darker area within the freeze and this is useful in confirming that the whole break has been treated. Larger breaks may need several applications. These are applied by working methodically around the edges of the break to ensure contiguous burns with minimal overlap (Fig. 100.15). Refreezing and freezing of the bare central RPE in large breaks are avoided to reduce the risk of RPE dispersion.23

In the presence of shallow subretinal fluid, the indentation of the tip of the cryoprobe approximates the pigment epithelium to the retina and both freeze almost simultaneously. If the breaks are more elevated the pigment epithelium cannot be apposed to the retina. Freezing of the pigment epithelium can then be clearly seen to precede freezing of the retina, sometimes by several seconds (Fig. 100.16). In this situation, what is the optimal end point of treatment: freezing of the pigment epithelium or the retina? This is a particularly important question given the concern about potential adverse effects of excessive cryotherapy on other tissues.24–26 In an experimental model the adhesions produced by freezing of the retinal pigment epithelium alone lacked the microvillous interdigitations normally present between pigment epithelium and retina. The resulting chorioretinal adhesion was weaker than when the freeze was allowed to extend to the retina.27 In practice, the chorioretinal adhesions that develop from freezing of the pigment epithelium alone seem to be sufficient. A further advantage of freezing the retina however, is that the “lighting up” of the retinal breaks is a useful confirmation that all the edges of the break have been treated.

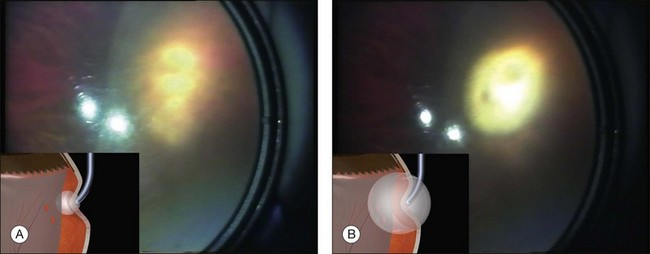

Cryotherapy to the disc or macula (Fig. 100.17) occurs when the indentation from the shaft of the probe is mistaken for its tip (“shaft indentation”) (Fig. 100.18). This cognitive problem can be avoided by encouraging trainees to intentionally indent posteriorly (without actually activating the cryoprobe!) (Fig. 100.19). They then become familiar with the distinctive appearance of shaft indentation.

Beginners find cryotherapy on anterior breaks challenging because the cryoprobe has a tendency to slip over the surface of the eye. This can be overcome with counter-traction from the bridle sutures on the opposite recti (Fig. 100.20). Alternatively, the cryoprobe is intentionally placed anterior to the break and the globe rotated using the tip of the probe. The pressure of the probe is then slightly released while the indent from the probe is viewed using indirect ophthalmoscopy. As the globe returns slowly to the primary position the tip indentation is seen to move. When the indentation of the tip is under the break a very small increase in the pressure applied stabilizes the globe and the cryoprobe is activated.

Diode laser

The delivery technique of transscleral diode laser uses a probe which indents the sclera under indirect ophthalmoscopic visualization. A diode laser aiming beam facilitates accurate placement of the tip. The end point of treatment can be difficult to titrate, particularly in blonde fundi, and over-treatment with choroidal hemorrhage and scleral thinning may occur during the learning curve.28 The theoretical advantages of diode laser (less inflammation, blood–ocular barrier breakdown and pigment dispersion) do not seem to translate into clinical practice as a large randomized trial failed to find any advantage over cryotherapy.29

Photocoagulation

Photocoagulation may be applied several days to weeks postoperatively once the retina has reattached.30,31 While visual recovery was faster in the postoperative laser retinopexy groups the final anatomical and visual results are comparable to cryopexy. Photocoagulation on the buckle is uncomfortable and requires the use of regional anesthesia. The main disadvantage of this technique is the need for an additional procedure.

Choice of retinopexy technique

Intraoperative cryopexy remains a quick and simple technique. The search for an alternative means of producing retinopexy is driven by the belief that cryotherapy is inherently dangerous. This view has been challenged.32

Manipulation of the globe after cryotherapy causes release of pigment into the vitreous cavity23 and some surgeons prefer to carry out cryotherapy at a later operative stage.

Choice of scleral explant

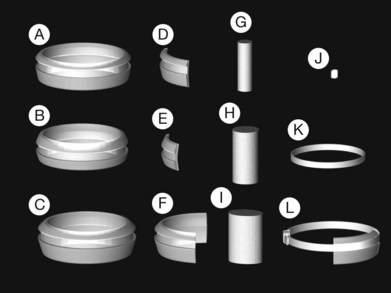

Historically, a number of materials have been used in the manufacture of explants.33 None of these seem to be as well tolerated as silicone rubber which is biologically inert and can be left in situ indefinitely.6,34

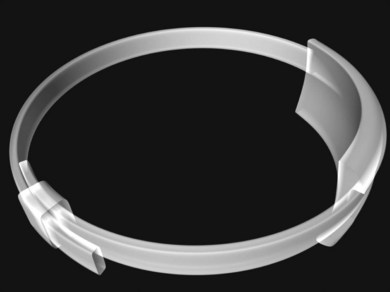

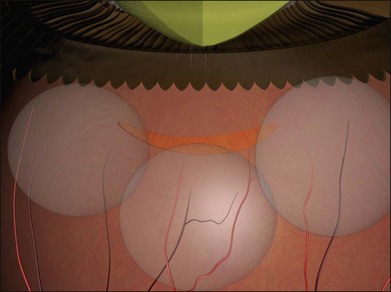

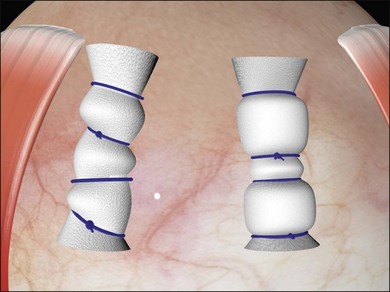

Two types of cylindrical silicone explant are currently in regular use, solid silicone tires and silicone sponges consisting of air-filled cells (Fig. 100.21). Early silicone sponges had communicating air cells and an increased risk of infection35 but this problem has been much reduced by the use of sponges with closed air cells.

Solid silicone is, for practical purposes, non-compressible. Silicone sponges, because of their cellular composition are easily deformable and compressible. When a sponge is initially sutured the sponge is compressed and the intraocular pressure rises. As the intraocular pressure subsequently falls to physiological levels the sponge expands facilitating closure of elevated retinal breaks. (Details of the mechanism of action of scleral buckles are described in Chapter 99, The effects and action of scleral buckles in the treatment of retinal detachment.)

The design of solid silicone tires reflects their original use as circumferential scleral implants. There is a groove on the upper surface with a rectangular profile to accommodate an overlying band. It was subsequently found that they can be used as explants.36 Some surgeons dispense with the band and use them as purely local explants.

Silicone tires are usually oriented circumferentially. Sponges may be oriented either circumferentially or radially. The geometry of the indent favors radial orientation of sponges when treating retinal tears.2 While the choice between tires and sponges is to some extent a matter of surgeon preference their different physical properties favor their use in different situations depending on the number, size and location of retinal breaks. This can be illustrated by some examples:

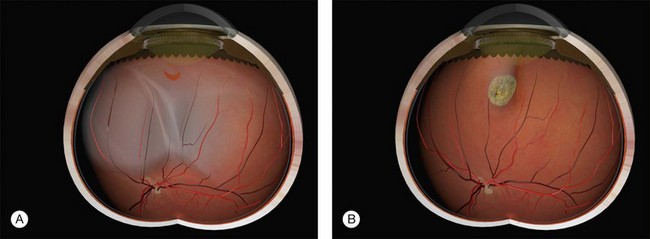

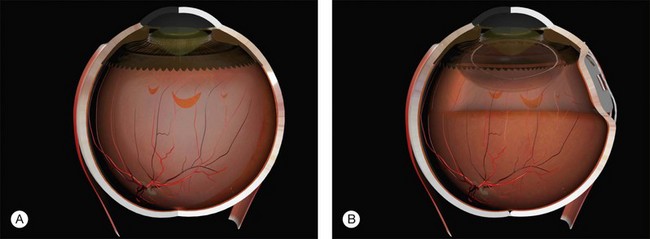

Example 1: A detachment with a single elevated equatorial tractional tear (Fig. 100.22). This may be closed successfully using a single radial sponge without drainage of subretinal fluid. If a silicone tire is used in the same situation the indent may not be high enough to close retinal breaks without subretinal fluid drainage and/or gas injection.

Example 2: A detachment due to a series of round retinal holes (Fig. 100.23). The holes are anterior to the equator at various distances from the ora. They may be treated with a circumferential explant. A very high indent is not required because there is no traction on the breaks and the fluid is very shallow. As the distance from the ora varies the broader indentation from a tire can close all the breaks.

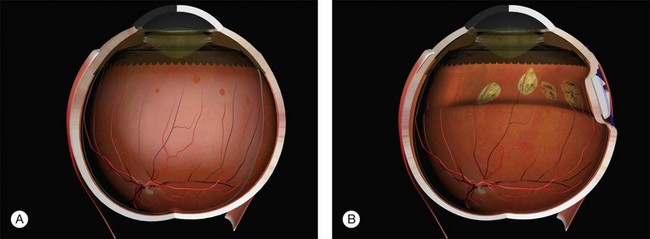

Example 3: A pseudophakic eye with a total retinal detachment. Good visualization of the peripheral retina is impeded by peripheral capsule opacification and limited pupil dilatation (Fig. 100.24). No tears are seen. An internal approach using pars plana vitrectomy has many advantages here.37 If this is not possible, an encircling tire may be used. The buckle may be secured just behind the rectus muscle insertions to support the anterior retina where the breaks are likely to be located. The tire supports the whole area of subretinal fluid (“dry-to-dry” buckling). The placement of an encircling silicone band in the groove of the tire maintains the height of the indent so that undetected retinal breaks remain closed.

Example 4: Three tractional tears are present (Fig. 100.25). They can be treated with separate radial sponges or with a single circumferential buckle.

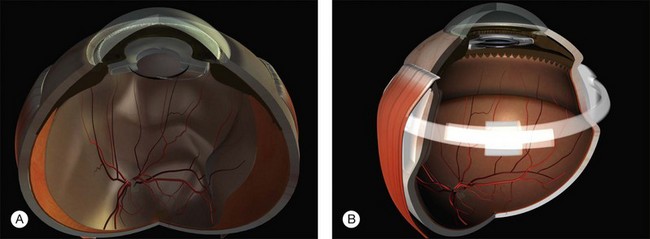

Example 5: Three tractional tears are again present but they are too close together to be easily closed with individual radial sponges (Fig. 100.26). A “raft” of radial sponges sewn side-to-side is possible but a circumferential buckle is an easier option. A high circumferential sponge may be used but it can be difficult to close all the breaks because of the variable distances from the limbus. Furthermore, high circumferential sponges are particularly likely to result in fishmouthing (Fig. 100.27). A circumferential tire combined with subretinal fluid drainage and/or gas injection may be used.

Example 6: A retinal dialysis. Provided the indent is high enough (a 3-mm circumferential sponge usually works well), it does not need to be very wide and subretinal fluid drainage is usually unnecessary (Fig. 100.28).38

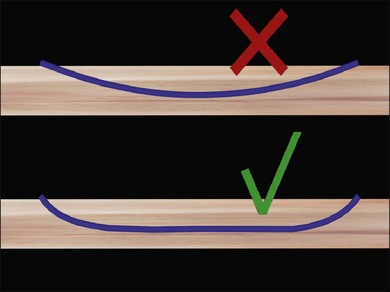

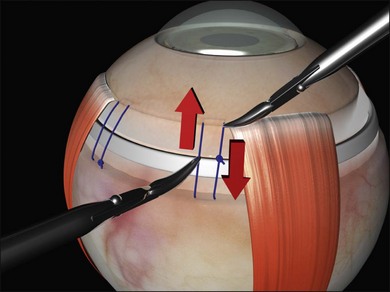

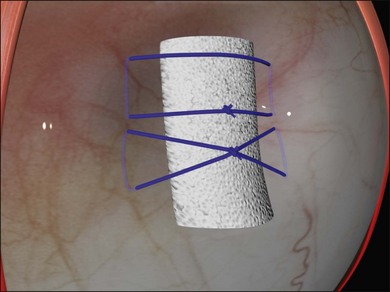

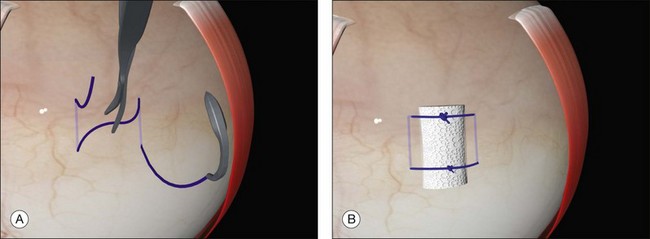

Scleral sutures

The distance between the bites is significantly greater than the width of the explant. This allows the sclera to partially envelop the explant, creating the indent. For example, when suturing a 5-mm sponge, the bites are placed 8 mm apart. Silicone tires generally need a bite separation 2 mm greater than their width. Failure to space the bites sufficiently reduces the height of the indent. Calipers are used to ensure accurate bite separation (Fig. 100.29). The bites pass in opposite directions, so that the mattress suture has a box configuration and the sutures do not cross over on the buckle. Crossing over of the sutures reduces the length of the indent (Fig. 100.30). A box suture may be difficult to achieve with posterior radial bites, as it is easier and safer to pass a bite anteroposteriorly than it is to pass it posteroanteriorly. Use of a double-armed suture allows two anteroposterior passes of the needle. Alternatively, a figure-of-8 suture may be converted to a box suture by dividing the suture between the bites (Fig. 100.31).

Fig. 100.29 Calipers used to ensure the correct suture bite separation – in this case 8 mm for a 5-mm sponge.

Fig. 100.30 A crossed mattress suture (bottom) does not support the ends of the sponge as well as a box suture (top).

Mattress sutures should have a square configuration, with the bites parallel to each other and the long axis of the buckle. Irregular nonparallel sutures cause less-effective indentation (Fig. 100.32).

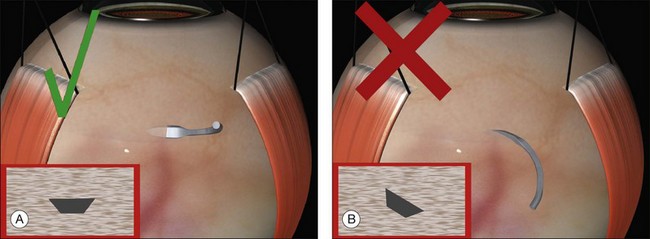

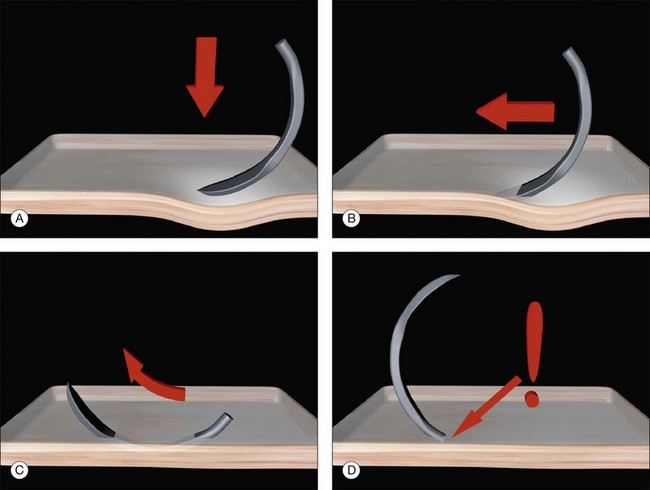

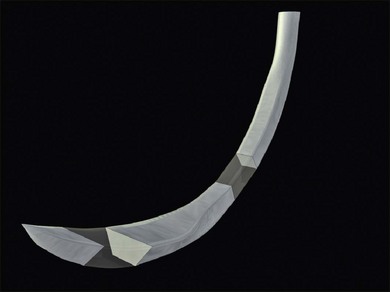

The sutures need to be placed partial thickness ( ) through the sclera. As the scleral is only 1 mm thick, care needs to be taken to avoid scleral perforation. A spatulated needle rather than a cutting needle is used. The spatulated needle profile has a flat top and bottom and cutting lateral edges (Fig. 100.33). The sclera has a pseudolamellar structure.39 When appropriately used, a spatulated needle tends to glide between the scleral lamellae.

) through the sclera. As the scleral is only 1 mm thick, care needs to be taken to avoid scleral perforation. A spatulated needle rather than a cutting needle is used. The spatulated needle profile has a flat top and bottom and cutting lateral edges (Fig. 100.33). The sclera has a pseudolamellar structure.39 When appropriately used, a spatulated needle tends to glide between the scleral lamellae.

The tip of the needle is placed on the sclera, so that the tangent of the tip is parallel with the surface of the eye. It is important to ensure the needle does not bank, as this may cause the needle to cut out laterally (Fig. 100.34). When placing posterior sutures, this is easiest to achieve while sitting on the opposite side of the eye from the surgical area (Fig. 100.35). In fact it is a good principle to always operate “over the cornea,” as this gives better access to the recesses of the sub-Tenon’s space.

Fig. 100.34 A spatulated flat should be laid flat on the sclera (A) – if it banks (B), it may cut out.

Fig. 100.35 Operate from the other side (“over the cornea”) for access to the posterior sub-Tenon’s space.

Gentle downward pressure creates a small indent (Fig. 100.36). The needle is now advanced, keeping the tangent of its tip parallel to the surface of the eye. This causes it to advance progressively deeper in to the sclera. Once it has reached the desired depth no more downward pressure is applied. The spatulated design of the needle allows it to glide (or delaminate) between the scleral lamellae at a constant depth.

Fig. 100.36 Safe passage of scleral sutures. The depth of the needle is gauged by its visibility throughout.

The depth of the needle passage is monitored continuously during its passage through the sclera. At a depth of 500 µm, the needle is only just visible. The depth of the needle can be varied during the pass. Downward pressure while advancing the needle will take it deeper into the sclera and slight rotation (or lifting) of the needle can be used to reduce its depth. While care must be taken not to perforate the sclera, the entrance and exit from the sclera should not be too shallow (Fig. 100.37). If the start or end of the bite is very superficial the sutures may partially tear out under tension. Once the bite is deemed of adequate length (usually 4–5 mm) the needle is rotated to bring the tip out of the sclera.

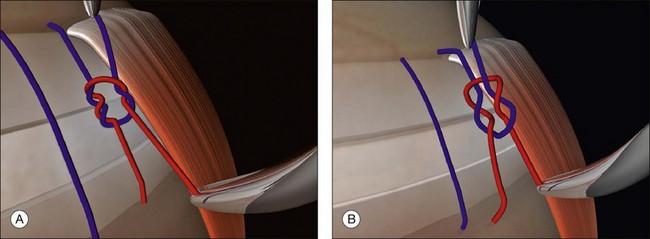

Tying the sutures

The aspiring vitreoretinal surgeon should have a good understanding of basic surgical principles. The properties of surgeons’ knots (Fig. 100.38A) and slip knots (Fig. 100.38B) are particularly important.40 Scleral mattress sutures have to be tied under tension to create an indent. There are a number of ways of doing this.

Prominent suture ends may erode through the conjunctiva and ultimately lead to extrusion of the buckle. Once the knots have been tied securely the sutures should therefore be rotated bimanually to leave the knot lying posteriorly (Fig. 100.39). If nylon is used the ends should be trimmed close to the knot.

Subretinal fluid drainage

Indications for drainage

There is no consensus on the role of subretinal fluid drainage. Approximation of retinal breaks alone is sufficient to cause retinal reattachment (see also Chapter 99, The effects and action of scleral buckles in the treatment of retinal detachment).41 Subretinal fluid drainage has been used to lower intraocular pressure but this can be achieved in other ways, for example by paracentesis.42 The anterior chamber depth is quickly restored particularly in myopic and pseudophakic eyes, allowing repeated paracentesis. A randomized control trial of medium complexity cases showed no advantage of subretinal fluid drainage.43

Technique of drainage

Timing

Subretinal fluid may be carried out at various stages in the operation. The “DACE” (Drain air cryotherapy explant) sequence was developed for bullous retinal detachments. Subretinal fluid drainage followed by air injection to reform the globe prevents parallax errors during break localization. It has also been argued that cryotherapy may cause vascular congestion of the choriocapillaris and that subretinal fluid drainage should not therefore follow cryotherapy.44 In practice, subretinal fluid drainage does not appear any more hazardous when performed after cryotherapy.45 It can even be performed at the end of the operation.46

Location of drain sites

The long ciliary neurovascular complexes run at 3 and 9 o’clock, and these sites should be avoided, as should the area around the vortex veins. Sites adjacent to (but not under) the horizontal recti are optimal from the perspective of avoiding choroidal vasculature.44

Drainage techniques

Cut down techniques

A scleral incision 3 mm in length is made in the sclera, repeatedly spreading the edges, then incising the base of the resulting groove (Fig. 100.40, available online). The choroid becomes increasingly visible in the base of the incision. Finally a small knuckle of bare choroid protrudes slightly.

Thermal choroidotomy may be used to reduce the risk of bleeding with this technique. A diathermy needle may be used to coagulate the choroidal vessels47 and a diathermy needle used to perforate the choroid.48 Alternatively, photocoagulation may be used. The tip of is laser endoprobe is positioned very close to the knuckle of choroid (Fig. 100.41). The laser is activated for 1–2 seconds at very high power (600 mW) until subretinal fluid is seen welling forward. The high beam divergence makes unintentional retinotomy unlikely and this technique has been used successfully in the presence of quite shallow subretinal fluid.49 Use of an indirect laser for this step avoids the expense of an endolaser probe.50

Single-stage techniques

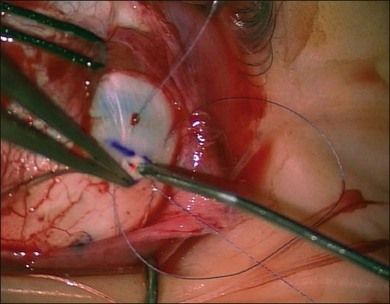

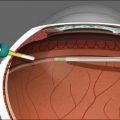

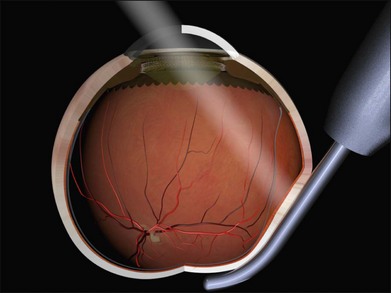

Charles has described a technique using a 25-gauge hypodermic needle attached to an open syringe under ophthalmoscopic visualization (Fig. 100.42). The needle enters the globe anteriorly and is passed under the buckle and obliquely posteriorly in the subretinal space.51 Retinal incarceration is extremely unlikely and any retinal breaks created will be in the bed of the buckle and therefore supported. An increased risk of intraocular bleeding has been reported however.52 This may be averted by increasing the intraocular pressure to close the choroidal vascular bed, for example, by tightening an encircling band prior to drainage.46

Suture needle drains use a spatulated needle held in a locking needle holder with 2.5 mm of the tip protruding (limiting the depth of penetration) (Fig. 100.43, available online).53 Very firm pressure on the globe with a forceps at a rectus insertion elevates the intraocular pressure, closing the choriocapillaris before and for 5 minutes after the drain. A single rapid and decisive stab is made into the sclera and the needle immediately withdrawn.

Fig. 100.43 Suture needle drain. Note firm pressure on the globe to close the choroidal vasculature.

It is also possible to penetrate the sclera and choroid together using a specially designed diathermy needle which cauterizes to reduce the risk of hemorrhage.54

Comparison of techniques

While performing cut down drainage, intraocular pressure elevation is avoided to prevent retinal incarceration. In needle drainage on the other hand there is no risk of incarceration (because the choroidotomy is so small) and a high intraocular pressure is desirable to reduce the risk of bleeding. When operating on bullous detachments, very rapid release of fluid can make it difficult to maintain a sufficient intraocular pressure and this may account for the increased risk of subretinal hemorrhage with this technique.55

After drainage

Whichever drainage technique is used, it is prudent to be prepared for postoperative hypotony. Prolonged hypotony is dangerous during buckling surgery. It may lead to suprachoroidal effusions and hemorrhage,56 hyphema, and pupil constriction. The scleral sutures should therefore have been pre-placed ready for tying and a syringe of air or saline with a small-bore needle at hand to reform the globe.

If subretinal fluid does not flow, or stops earlier than anticipated, the drain site is inspected to exclude a retinal incarceration and reassess the depth of subretinal fluid at the drain site. Star-shaped folds radiating from the drain site indicate a retinal incarceration (Fig. 100.44). It is not generally possible to re-posit the incarcerated retina in the eye and dangerous to try. The site of the incarceration is supported by an explant to relieve traction at this site, combined with retinopexy if there is also a retinal break.

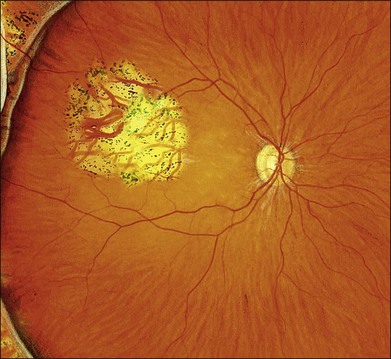

The major complication of subretinal fluid drainage is choroidal hemorrhage. Subretinal blood tends to gravitate to the most dependent area of subretinal fluid – the macula if this is detached. The rate at which this occurs is probably contingent on the viscosity of the subretinal fluid (and therefore the chronicity of the detachment). It can have serious consequences for visual recovery, so steps should be taken first to limit bleeding and second, to displace the hemorrhage. First the intraocular pressure is elevated, either by tightening sutures or intravitreal injection (cut down drains should be closed with the prepared sutures if this is done). The patient’s head may also be tilted towards the drain site. Subfoveal hemorrhage may be displaced pneumatically57 or removed subsequently by vitrectomy.58

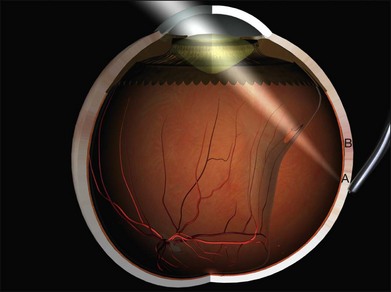

Air injection

When only small holes are present a soft globe may be reformed with saline but in the presence of large tears the fluid quickly leaves the eye and the eye will re-soften. The surface tension of a gas bubble prevents its passage through breaks. An additional advantage of air and gas injections is their ability to supplement the external buckling effect with internal tamponade of breaks. The major disadvantage of using air or gas is that they may make fundal view difficult particularly if the injection technique is poor. The gas injection technique is described in detail in Chapter 103, Pneumatic retinopexy, but there are some special considerations relating to the use of gases in buckling surgery.

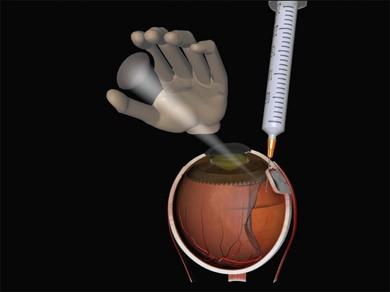

Use of air or gas to reform a collapsed globe entails injecting into a soft eye. A number of modifications to the basic pneumatic retinopexy technique can make this easier. Use of an air pump can be particularly helpful for the less-experienced surgeon (Fig. 100.45). A 23-gauge needle is attached to the air line and the pump pressure set at a physiological level (i.e., 20 mmHg) before being clamped. The needle is introduced into the eye taking the precautions described in Chapter 103, Pneumatic retinopexy. The clamp on the air line is released and air rapidly enters the vitreous cavity until the preset pressure on the pump is reached. The rate of air flow is optimal and the final pressure physiological. This technique is relatively forgiving of errors in placement of the needle (and fish eggs are virtually never encountered).

Macular folds are a rare complication of the combination of subretinal fluid, air injection, and buckling (Fig. 100.46).59,60 There is some uncertainty about the best way to avoid this devastating complication. Face-down posturing immediately after surgery to displace subretinal fluid away from the macula may be helpful.

Fig. 100.46 Compression fold following drain, air, and explant. This may be avoided by prone posturing.

If general anesthesia is used nitrous oxide should be discontinued at least 15 minutes before the injection to prevent unpredictable expansion of the bubble.61 Avoiding the use of nitrous oxide altogether removes this risk.

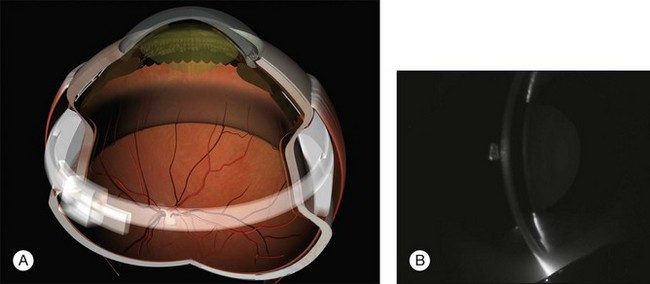

Encirclement

Segmental buckles provide local support which often fades. This may lead to reopening of breaks if insufficient retinopexy has been applied.22 Encirclement produces permanent support of the vitreous base retina. Indeed, encirclement has been used without any retinopexy62: as the breaks are permanently supported there is no need to seal them.

The indications and evidence for encirclement are reviewed more extensively in Chapter 105, Optimal procedures for retinal detachment repair. There is little evidence to support the routine use of encirclement in buckling surgery and the procedure appears to have a significantly greater risk of complications than a segmental buckle. In practice, a case-by-case judgment has to be made on whether the benefits (the increased chance of success is probably quite modest) justify the risks.

Encirclement has a particular role in certain situations:

• Very extensive scleromalacia

• Extensive detachment in which breaks are difficult to detect (for example in some pseudophakic eyes with small anterior breaks and capsular phimosis).

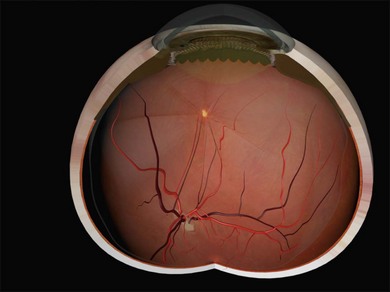

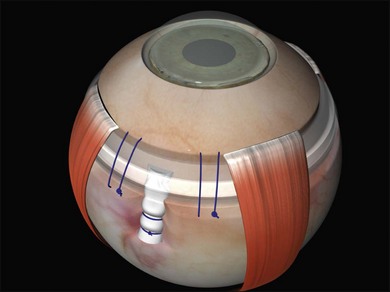

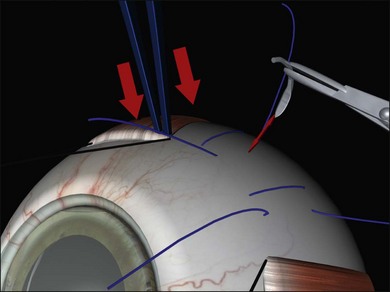

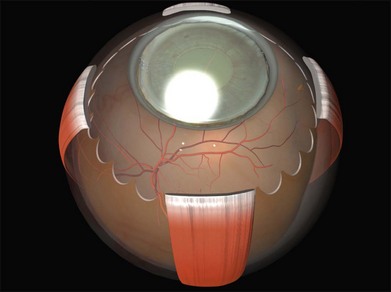

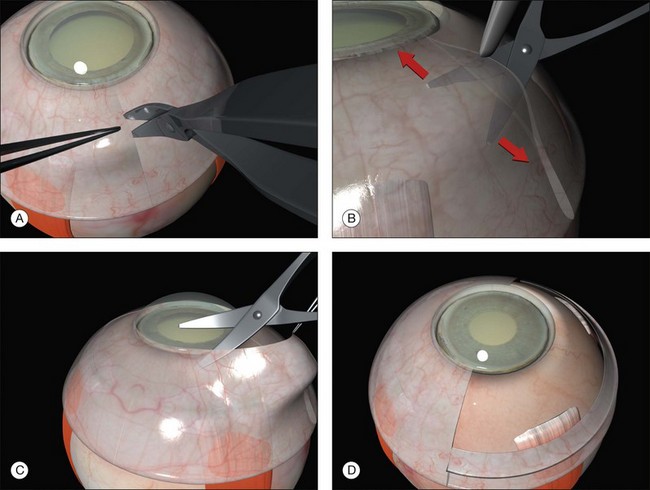

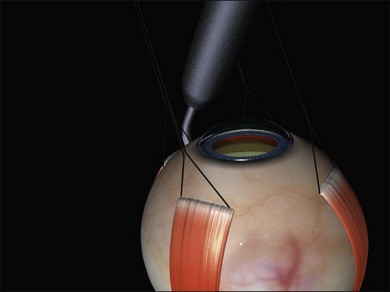

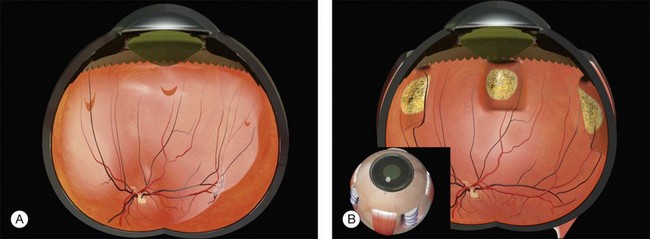

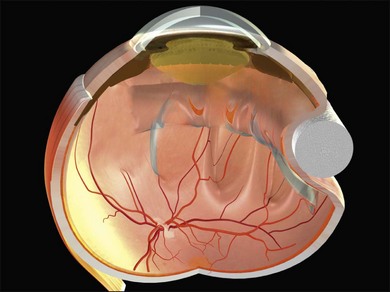

Encirclement is produced with a combination of a local silicone tire (confined to the areas of visible the breaks) with a 2-mm band, which lies in the gutter of the tire and encircles the globe before being attached to itself (Fig. 100.47). The 2-mm band is often too narrow to support breaks and its primary purpose is to maintain the height of the indent from the tire.

1. A 360° peritomy with slinging of all four rectus muscles.

2. Break localization, retinopexy and pre-placement of the mattress sutures of the tire. Generally two sutures are required per quadrant.

3. Threading the tire and band together under the recti and mattress sutures. Ensure that both limbs of all the mattress sutures are above the buckle as it is not uncommon to leave one under the encirclement by mistake. Some thought needs to be given to where the ends of the band will be secured at this stage. It is also important to ensure that the band does not become twisted. An oblique trimming of the ends allows the orientation to be checked after the band has been passed around the globe (as a 180° twist will be immediately apparent).

4. Subretinal fluid drainage is required in the majority of cases. The exact stage at which it is performed is variable but it may be done now to create space for the indent.

5. Tighten the mattress sutures over the tire to create a local indent.

6. Place a small holding stitch over the band in each quadrant where there is no tire to stop it bow stringing forward when tightened. These are placed at the equator (approximately 12 mm behind the limbus).

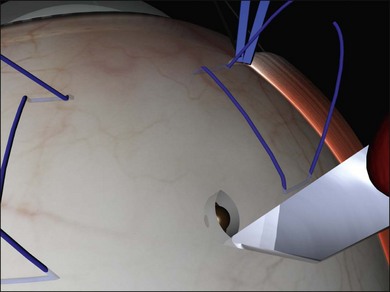

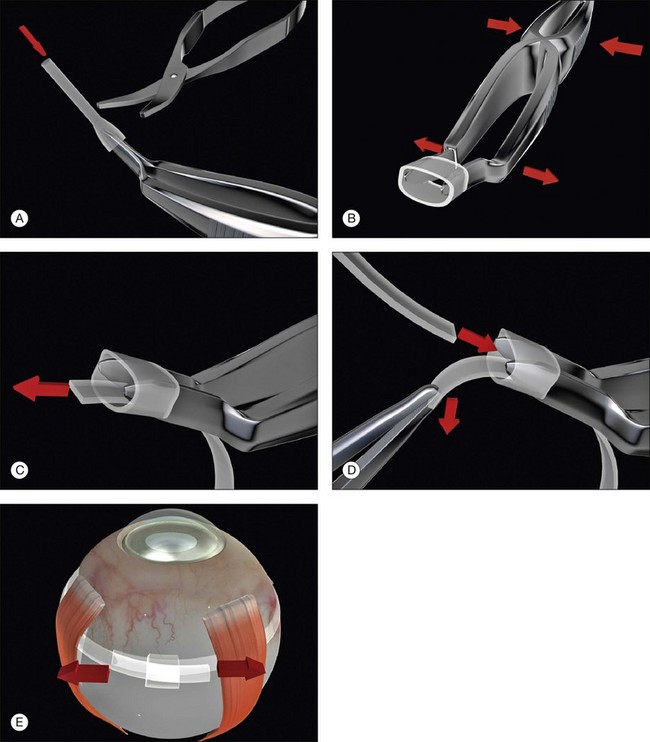

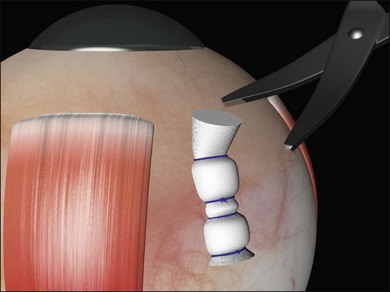

7. Fasten the ends of the band to each other. A Watzke sleeve is a small silastic tube designed to secure the ends and allow adjustment of the tension in the band. The steps for engaging the ends of the band in the sleeve with a specially designed cross acting (“Watzke”) forceps are illustrated (Fig. 100.48).

8. The ends of the band are pulled to create the encircling indent. A 6-mm shortening will produce approximately a 1-mm indent, irrespective of the size of the globe. The end point of this tightening is best judged ophthalmoscopically; a shallow indent should be just visible. The practice of tightening the band to reform the eye after drainage is dangerous as it may produce a grossly excessive indentation.

9. The optic nerve perfusion should be checked and, if necessary steps taken to normalize it such as paracentesis, subretinal fluid drainage, or adjusting the buckle.

Final examination of the retina

The buckle should be in the correct position and of sufficient height to support all the retinal breaks (Fig. 100.49). Unsupported breaks may be supported by moving existing explants or by placing additional explants as required (e.g., by the addition of more radial sponges under encircling circumferential explants).

Judging the correct height of the buckle can be difficult, as even breaks that are not fully closed at the end of surgery may close postoperatively allowing the RPE to pump out the residual subretinal fluid. If the contour of the detached retina follows that of the buckle, the break is likely to close (Fig. 100.50). The height of the buckle may be adjusted by readjusting scleral sutures (if they have been tied on bows) or replacing scleral sutures (usually with wider bites). Otherwise, the buckle may be replaced. The height of the buckle may also be adjusted by subretinal fluid drainage at this stage. A simpler alternative is adjunctive pneumatic retinopexy.63

Closure

The risk of buckle extrusion may be reduced by trimming any protruding edges of sponges (Fig. 100.51), rotating radial mattress sutures so that the knots lie posteriorly and ensuring that the buckles are covered by Tenon’s capsule. This may entail closure of Tenon’s as a separate layer before closure of conjunctiva, particularly with radial sponges where the risk of exposure and extrusion is much greater.64,65

Fig. 100.51 Trimming protruding pieces of explant does not compromise the indent and reduces the risk of extrusion.

A subconjunctival injection of broad-spectrum antibiotic and steroid may be given.

Outcomes

Reported outcomes for primary success with scleral bucking are generally high. In a series of 4325 patients, a success rate of 84% was achieved following a single operation.66 There is some variation in reported success rates and many failures are avoidable.67,68 This underlines the importance of good surgical technique in achieving a satisfactory result.

Functional success with recovery of central vision is somewhat lower than anatomical success69 and depends on the stage of presentation and the duration of macular detachment. It is important to remember that binocular visual function, ocular cosmesis and ocular comfort are the most important outcomes for the patient. Measures taken to maximize the anatomical success rate (e.g., the routine use of large encirclements in simple cases) may not therefore be justified if they carry a greater morbidity.70

Postoperative complications

Recurrent retinal detachment

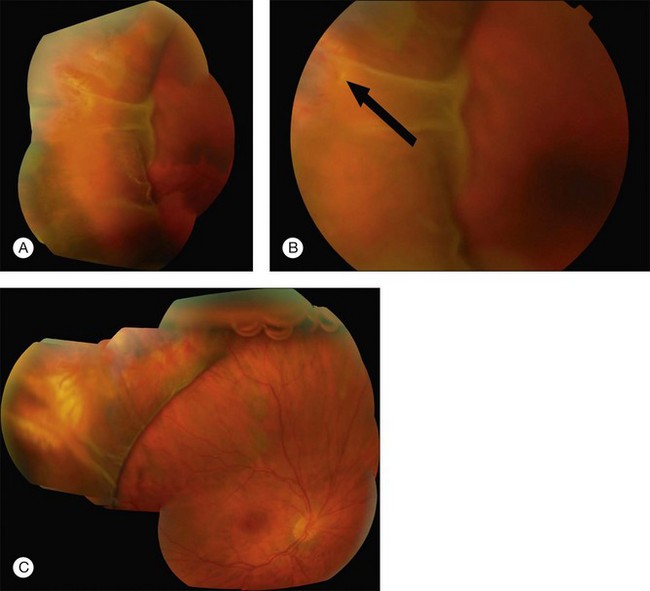

Persistent subretinal fluid is often seen in the early postoperative period, particularly if a nondrainage operation has been performed. Resorption of fluid may take much longer (Fig. 100.52), particularly in chronic detachments with subretinal precipitates and demarcation lines.71 Persistence of subretinal fluid alone is not an indication for revision surgery. Indications for early revision surgery are a visible open retinal break or increasing subretinal fluid.72

Recurrent detachment is often due to errors in the initial surgery.9 Successful revision surgery starts with an analysis of the cause of failure. Is there an open break? Are the indents in the right place? Are they high enough to close the breaks? These questions are answered by carefully observing the distribution of subretinal fluid, the presence of subretinal fluid on indents and visibly open or unsupported breaks.9

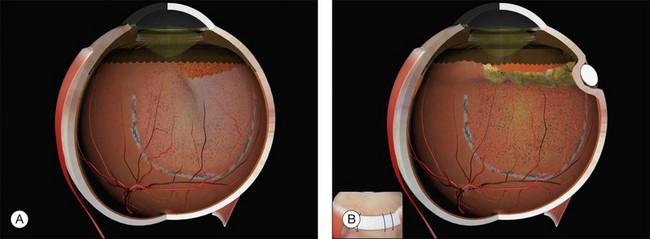

Example 1: Inadequate buckle – A patient with a shallow inferior detachment due to several atrophic holes underwent a nondrainage procedure with a local circumferential tire. Postoperatively, the distribution of subretinal fluid was unchanged from before the operation, implying that one of the original breaks remained open (Fig. 100.53). There was subretinal fluid on the indent at 6 o’clock communicating with an open break. The height of the buckle was uneven and at revision surgery no sutures were found near the site of the break. The addition of extra sutures to support this area successfully reattached the retina.

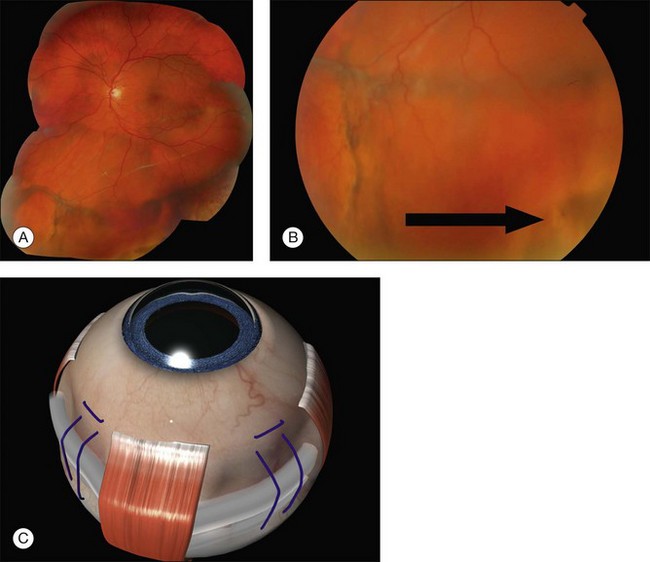

Example 2: Missed retinal break – A child presented with an extensive inferior detachment. The operation note stated that no definite breaks were found but cryotherapy and radial sponge were applied to a ‘thin area with probable hole’ inferiorly. The amount and distribution of fluid was unchanged postoperatively. The fluid distribution did not obey Lincoff’s laws. This suggested a break had been missed at the original surgery. At repeat surgery, a superonasal retinal dialysis was found (Fig. 100.54).

Example 3: Misplaced buckle – A patient presented with recurrent retinal detachment following an encircling procedure. There was no subretinal fluid on the indent. Closer examination revealed a small tear behind the indentation (Fig. 100.55). This was managed by locally augmenting the encirclement with a radial explant (Fig. 100.56).

Example 4: Fishmouthing – A patient underwent a local circumferential sponge nondrainage operation for a detachment due to several small tractional tears in one quadrant of the retina. Postoperatively, persistent subretinal fluid with folds of retina on the buckle were present (Fig. 100.57). One of these folds was in communication with a retinal tear. A diagnosis of fishmouthing was made.73 Injection of 0.3 mL 100% SF6 quickly resolved the problem.74

Example 5: Misplaced buckle: Radial sponge malposition in the radial meridian – A nondrainage operation with a radial sponge was used for a detachment due to a single tear. The amount and distribution of fluid were unchanged postoperatively (Fig. 100.58). The tear was on the edge of the indentation. Placement of a radial sponge in the correct meridian closed the break.

Proliferative vitreoretinopathy, the most important cause of ultimate failure to reattach the retina, is discussed in Chapter 107, Proliferative vitreoretinopathy.

Glaucoma

Retinal detachment is associated with glaucoma,75 so in some cases postoperative glaucoma may have been present preoperatively.

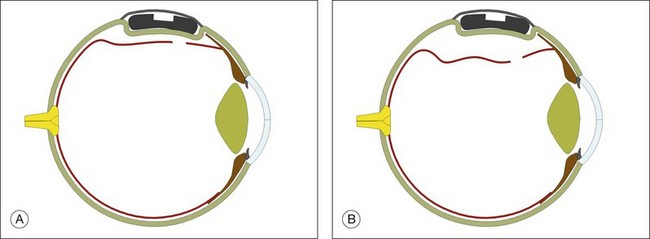

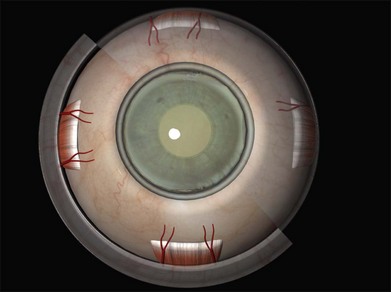

A steroid response is the commonest cause of open angle glaucoma after buckling surgery. Most cases of buckle-related angle closure glaucoma occur without pupil block.76 The central anterior chamber is shallow due to forward displacement of the ciliary body (Fig. 100.59). This may be due to the combined effects of interrupted choroidal venous drainage and the mass effect of a large explant. This condition does not respond to iridotomy or miosis (which tends to exacerbate it). Most cases resolve after 1 week with conservative measures including steroids, cycloplegia, and ocular hypotensive agents. In intractable cases, the Watzke sleeve may need to be loosened or the band divided.

Epiretinal membranes

Epiretinal membranes at the macula are the commonest cause of visual loss after successful scleral buckling.77–79 Their management is discussed in Chapter 116, Macular epiretinal membranes.

Extrusion/infection

These typically present several weeks or months postoperatively as an inflamed eye with purulent discharge. Even if exposure of the buckle is not evident, it is often possible to express some pus through associated conjunctival dehiscence. As infection and extrusion are often associated, it can be difficult to establish which comes first. The risk seems to be heavily influenced by the surgical technique used, radial sponges having a greater risk than circumferential ones.65 This fact, together with the delayed presentation, suggests that in most cases microorganisms gain access to the explants though conjunctival dehiscences over protruding segment of buckle or suture rather than being introduced at the time of surgery. This highlights the importance of trimming the ends of sutures and explants and covering them well during closure. Closure of Tenon’s capsule and conjunctiva in separate layers may be the best way of achieving this, especially if the conjunctiva is particularly thin.

Bacteria produce a biofilm coating on explants which makes it impossible to eradicate them medically.80 The only definitive treatment is removal of the explant.81 Provided adequate retinopexy has been performed recurrent retinal detachment is unusual.82,83 If there is any doubt about this supplementary retinopexy may be carried out around the breaks before removing the buckle.

Buckle exposure tends to follow a relatively chronic course but occasionally patients develop acute sight-threatening complications such as endophthalmitis or scleritis84,85 requiring urgent removal of all foreign material (explants and sutures) and local and systemic antibiotics.

Band migration

Encircling bands may intrude or migrate over the surface of the eye, usually anteriorly.

Diplopia

Diplopia is common after scleral buckling surgery.86 It tends to improve with time and intervention is only indicated for persisting diplopia which does not respond to prisms. Removal of the explant alone may cure the problem.87 Strabismus surgery can be challenging due to the presence of buckles and adhesions. In patients with very extensive buckles which cannot safely be removed repeated injections of botulinum toxin may be useful.88

Anterior segment ischemia

Anterior segment ischemia is now rare, as very high encirclements and rectus disinsertion, both of which compromise the uveal circulation, are rarely used. Patients with sickle cell disease are at particularly high risk89 and may benefit from exchange transfusion particularly if an encircling buckle has to be used. Presenting features are corneal edema, pain, anterior chamber flare, and a deep anterior chamber. The intraocular pressure may be high initially but falls as the ciliary body fails. Mild cases may be managed with topical steroids but severe cases carry a poor prognosis and loosening or division of the band should be considered.

1 Sodhi A, Leung LS, Do DV, et al. Recent trends in the management of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Surv Ophthalmol. 2008;53:50–67.

2 Lincoff H. Radial buckling in the repair of retinal detachment. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1976;16:127–134.

3 Schepens CL. Management of retinal detachment. Ophthalmic Surg. 1994;25:427–431.

4 Schepens CL, Okamura ID, Brockhurst RJ. The scleral buckling procedures. I. Surgical techniques and management. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1957;58:797–811.

5 Custodis E. Treatment of retinal detachment by circumscribed diathermal coagulation and by scleral depression in the area of tear caused by imbedding of a plastic implant. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd Augenarztl Fortbild. 1956;129:476–495.

6 Lincoff H, McLean JM. Modifications to the Custodis procedure. II. A new silicone implant for large tears. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967;64:877–879.

7 Demer JL, Miller JM, Poukens V. Surgical implications of the rectus extraocular muscle pulleys. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 1996;33:208–218.

8 White MH, Lambert HM, Kincaid MC, et al. The ora serrata and the spiral of Tillaux. Anatomic relationship and clinical correlation. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:508–511.

9 Lincoff H, Kreissig I. Extraocular repeat surgery of retinal detachment. A minimal approach. Ophthalmology. 1996;103:1586–1592.

10 Chignell AH, Markham RH. Retinal detachment surgery. Buckling procedures and drainage of subretinal fluid. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1977;97:474–477.

11 Lincoff H, Gieser R. Finding the retinal hole. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971;85:565–569.

12 Sasoh M. The frequency of subretinal fluid drainage and the reattachment rate in retinal detachment surgery. Retina. 1992;12:113–117.

13 Wilkinson CP. What ever happened to bilateral patching? Retina. 2005;25:393–394.

14 Lai MM, Lai JC, Lee WH, et al. Comparison of retrobulbar and sub-Tenon’s capsule injection of local anesthetic in vitreoretinal surgery. Ophthalmology. 2005;112:574–579.

15 Mein CE, Flynn HWJ. Augmentation of local anesthesia during retinal detachment surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1989;107:1084.

16 Bergman L, Backmark I, Ones H, et al. Preoperative sub-Tenon’s capsule injection of ropivacaine in conjunction with general anesthesia in retinal detachment surgery. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:2055–2060.

17 King LMJ, Schepens CL. Limbal peritomy in retinal detachment surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974;91:295–298.

18 Gass JD. Fenestrated muscle hook for retinal detachment surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967;77:676.

19 Gass JD. Scleral marker for retinal detachment surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1966;76:700–701.

20 Gilbert C, McLeod D. D-ACE surgical sequence for selected bullous retinal detachments. Br J Ophthalmol. 1985;69:733–736.

21 Stanford MR, Chignell AH. Surgical treatment of superior bullous rhegmatogenous retinal detachments. Br J Ophthalmol. 1985;69:729–732.

22 Chignell AH, Wong D. The role of induced choroidal retinal adhesion in retinal detachment surgery. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1986;105:580–582.

23 Singh AK, Michels RG, Glaser BM. Scleral indentation following cryotherapy and repeat cryotherapy enhance release of viable retinal pigment epithelial cells. Retina. 1986;6:176–178.

24 Johnson RN, Irvine AR, Wood IS. Endolaser, cryopexy, and retinal reattachment in the air-filled eye. A clinicopathologic correlation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1987;105:231–234.

25 Campochiaro PA, Kaden IH, Vidaurri-Leal J, et al. Cryotherapy enhances intravitreal dispersion of viable retinal pigment epithelial cells. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103:434–436.

26 Jaccoma EH, Conway BP, Campochiaro PA. Cryotherapy causes extensive breakdown of the blood-retinal barrier. A comparison with argon laser photocoagulation. Arch Ophthalmol. 1985;103:1728–1730.

27 Laqua H, Machemer R. Repair and adhesion mechanisms of the cryotherapy lesion in experimental retinal detachment. Am J Ophthalmol. 1976;81:833–846.

28 Haller JA, Blair N, de Juan EJ, et al. Transscleral diode laser retinopexy in retinal detachment surgery: results of a multicenter trial. Retina. 1998;18:399–404.

29 Steel DH, West J, Campbell WG. A randomized controlled study of the use of transscleral diode laser and cryotherapy in the management of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Retina. 2000;20:346–357.

30 Veckeneer M, Van Overdam K, Bouwens D, et al. Randomized clinical trial of cryotherapy versus laser photocoagulation for retinopexy in conventional retinal detachment surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;132:343–347.

31 Lira RP, Takasaka I, Arieta CE, et al. Cryotherapy vs laser photocoagulation in scleral buckle surgery: A randomized clinical trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2010;128:1519–1522.

32 Lincoff H, Kreissig I. Cryopexy is not as bad as all that. Retina. 1998;18:486–488.

33 Baino F. Scleral buckling biomaterials and implants for retinal detachment surgery. Med Eng Phys. 2010;32:945–956.

34 Schepens CL, Okamura ID, Brockhurst RJ, et al. Scleral buckling procedures. V. Synthetic sutures and silicone implants. Arch Ophthalmol. 1960;64:868–881.

35 Russo CE, Ruiz RS. Silicone sponge rejection. Early and late complications in retinal detachment surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1971;85:647–650.

36 Aaberg TM, Wiznia RA. The use of solid soft silicone rubber exoplants in retinal detachment surgery. Ophthalmic Surg. 1976;7:98–105.

37 Heimann H, Bartz-Schmidt KU, Bornfeld N, et al. Scleral buckling versus primary vitrectomy in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment: a prospective randomized multicenter clinical study. Ophthalmology. 2007;114:2142–2154.

38 Stoffelns BM, Richard G. Is buckle surgery still the state of the art for retinal detachments due to retinal dialysis? J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2010;47:281–287.

39 Watson PG, Young RD. Scleral structure, organisation and disease. A review. Exp Eye Res. 2004;78:609–623.

40 Eisner G. Eye surgery: An introduction to operative technique. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1990.

41 Lincoff H, Kreissig I. The treatment of retinal detachment without drainage of subretinal fluid. (Modifications of the Custodis procedure. VI). Trans Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1972;76:1121–1133.

42 Ruiz RS, Drouilhet JH, Salmonsen PC. Paracentesis in scleral buckling procedures. Ophthalmic Surg. 1979;10:71–73.

43 Hilton GF, Grizzard WS, Avins LR, et al. The drainage of subretinal fluid: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Retina. 1981;1:271–280.

44 Johnston GP, Okun E, Boniuk I, et al. Drainage of subretinal fluid: why, when, where and how. Mod Probl Ophthalmol. 1975;15:197–206.

45 Pearce IA, Wong D, McGalliard J, et al. Does cryotherapy before drainage increase the risk of intraocular haemorrhage and affect outcome? A prospective, randomised, controlled study using a needle drainage technique and sustained ocular compression. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;81:563–567.

46 Jaffe GJ, Brownlow R, Hines J. Modified external needle drainage procedure for rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Retina. 2003;23:80–85.

47 Freeman HM, Schepens CL. Innovations in the technique for drainage of subretinal fluid, transillumination and choroidal diathermy. Mod Probl Ophthalmol. 1975;15:119–126.

48 Saran BR, Brucker AJ, Maguire AM. Drainage of subretinal fluid in retinal detachment surgery with the El-Mofty insulated diathermy electrode. Retina. 1994;14:344–347.

49 Ryan EHJ, Arribas NP, Olk RJ, et al. External argon laser drainage of subretinal fluid using the endolaser probe. Retina. 1991;11:214–218.

50 Pitts JF, Schwartz SD, Wells J, et al. Indirect argon laser drainage of subretinal fluid. Eye (Lond). 1996;10:465–468.

51 Charles ST. Controlled drainage of subretinal and choroidal fluid. Retina. 1985;5:233–234.

52 Burton RL, Cairns JD, Campbell WG, et al. Needle drainage of subretinal fluid. A randomized clinical trial. Retina. 1993;13:13–16.

53 Raymond GL, Lavin MJ, Dodd CL, et al. Suture needle drainage of subretinal fluid. Br J Ophthalmol. 1993;77:428–429.

54 Meyer-Schwickerath G, Klein M. Drainage of subretinal fluid with a cathode needle. Mod Probl Ophthalmol. 1975;15:154–157.

55 Aylward GW, Orr G, Schwartz SD, et al. Prospective, randomised, controlled trial comparing suture needle drainage and argon laser drainage of subretinal fluid. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79:724–727.

56 Aaberg TM, Maggiano JM. Choroidal edema associated with retinal detachment repair: experimental and clinical correlation. Mod Probl Ophthalmol. 1979;20:6–15.

57 Sarrafizadeh R, Williams GA. Submacular hemorrhage during scleral buckling surgery treated with an intravitreal air bubble. Retina. 2000;20:415–417.

58 Rubsamen PE, Flynn HWJ, Civantos JM, et al. Treatment of massive subretinal hemorrhage from complications of scleral buckling procedures. Am J Ophthalmol. 1994;118:299–303.

59 Twomey JM, Leaver PK. Retinal compression folds. Eye (Lond). 1988;2:283–287.

60 Elliott AJ, Scott JD. Retinal compression folds after surgery for acute bullous retinal detachment. Eye (Lond). 1989;3:100.

61 Stinson TWR, Donlon JVJ. Interaction of intraocular air and sulfur hexafluoride with nitrous oxide: a computer simulation. Anesthesiology. 1982;56:385–388.

62 Figueroa MS, Corte MD, Sbordone S, et al. Scleral buckling technique without retinopexy for treatment of rhegmatogeneous: a pilot study. Retina. 2002;22:288–293.

63 Sabates WI, Abrams GW, Swanson DE, et al. The use of intraocular gases. The results of sulfur hexafluoride gas in retinal detachment surgery. Ophthalmology. 1981;88:447–454.

64 Arribas NP, Olk RJ, Schertzer M, et al. Preoperative antibiotic soaking of silicone sponges. Does it make a difference? Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1684–1689.

65 Brown DM, Beardsley RM, Fish RH, et al. Long-term stability of circumferential silicone sponge scleral buckling exoplants. Retina. 2006;26:645–649.

66 Thelen U, Amler S, Osada N, et al. Outcome of surgery after macula-off retinal detachment – results from MUSTARD, one of the largest databases on buckling surgery in EuropeResults from a large German case series. Acta Ophthalmol. 2010.

67 Smiddy WE, Glaser BM, Michels RG, et al. Scleral buckle revision to treat recurrent rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Ophthalmic Surg. 1990;21:716–720.

68 Rachal WF, Burton TC. Changing concepts of failures after retinal detachment surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97:480–483.

69 Wilkinson CP. Mysteries regarding the surgically reattached retina. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2009;107:55–57.

70 Kreissig I. [Treatment of primary retinal detachment. Minimal extraocular or intraocular?]. Ophthalmologe. 2002;99:474–484.

71 Robertson DM. Delayed absorption of subretinal fluid after scleral buckling procedures. Am J Ophthalmol. 1979;87:57–64.

72 Chignell AH, Talbot J. Absorption of subretinal fluid after nondrainage retinal detachment surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:635–637.

73 Pruett RC. The fishmouth phenomenon. I. Clinical characteristics and surgical options. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95:1777–1781.

74 Norton EW. Use of gas in retinal surgery. Management of the fishmouth phenomenon. Trans Ophthalmol Soc U K. 1980;100:66–68.

75 Phelps CD, Burton TC. Glaucoma and retinal detachment. Arch Ophthalmol. 1977;95:418–422.

76 Perez RN, Phelps CD, Burton TC. Angel-closure glaucoma following scleral buckling operations. Trans Sect Ophthalmol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1976;81:247–252.

77 Tanenbaum HL, Schepens CL, Elzeneiny I, et al. Macular pucker following retinal detachment surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1970;83:286–293.

78 Wilkinson CP. Visual results following scleral buckling for retinal detachments sparing the macula. Retina. 1981;1:113–116.

79 Lobes LAJ, Burton TC. The incidence of macular pucker after retinal detachment surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 1978;85:72–77.

80 Holland SP, Pulido JS, Miller D, et al. Biofilm and scleral buckle-associated infections. A mechanism for persistence. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:933–938.

81 Smiddy WE, Miller D, Flynn HWJ. Scleral buckle removal following retinal reattachment surgery: clinical and microbiologic aspects. Ophthalmic Surg. 1993;24:440–445.

82 Hilton GF, Wallyn RH. The removal of scleral buckles. Arch Ophthalmol. 1978;96:2061–2063.

83 James M, O’Doherty M, Beatty S. Buckle-related complications following surgical repair of retinal dialysis. Eye (Lond). 2008;22:485–490.

84 Folk JC, Cutkomp J, Koontz FP. Bacterial scleral abscesses after retinal buckling operations. Pathogenesis, management, and laboratory investigations. Ophthalmology. 1987;94:1148–1154.

85 Rich RM, Smiddy WE, Davis JL. Infectious scleritis after retinal surgery. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;145:695–699.

86 Farr AK, Guyton DL. Strabismus after retinal detachment surgery. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2000;11:207–210.

87 Fison PN, Chignell AH. Diplopia after retinal detachment surgery. Br J Ophthalmol. 1987;71:521–525.

88 Scott AB. Botulinum treatment of strabismus following retinal detachment surgery. Arch Ophthalmol. 1990;108:509–510.

89 Ryan SJ, Goldberg MF. Anterior segment ischemia following scleral buckling in sickle cell hemoglobinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1971;72:35–50.

) portion of the insertion to facilitate suturing seems to have little effect on ocular motility. Note that a vortex vein is usually present under the temporal edge of the superior oblique insertion.

) portion of the insertion to facilitate suturing seems to have little effect on ocular motility. Note that a vortex vein is usually present under the temporal edge of the superior oblique insertion.

circle needle – a

circle needle – a  circle may be needed when access is difficult (e.g., posterior scleral sutures).

circle may be needed when access is difficult (e.g., posterior scleral sutures). of the distance from its tip in a curved (e.g., Barraquer) needle holder.

of the distance from its tip in a curved (e.g., Barraquer) needle holder.