35

Systemic Sclerosis and Sclerodermoid Disorders

Systemic Sclerosis (SSc)

• Etiology unknown but pathogenesis involves vasculopathy, endothelial dysfunction, tissue fibrosis, and immune system activation.

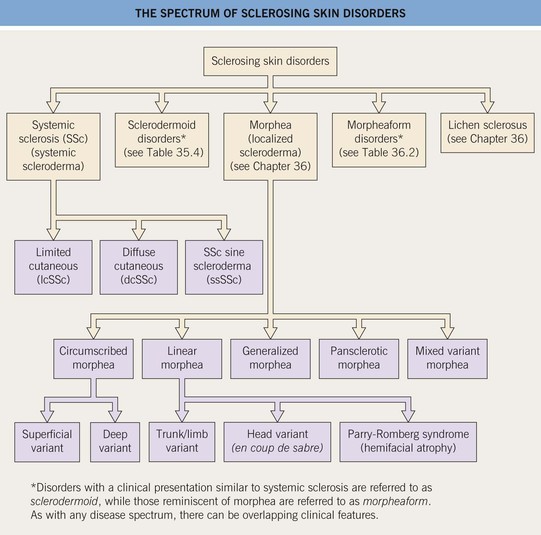

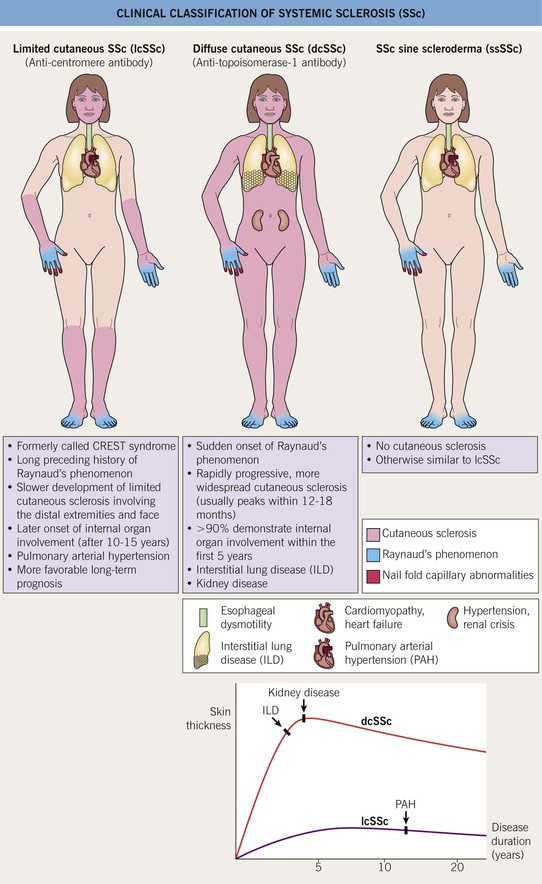

• There are three major clinical subtypes of SSc, based on the amount of skin sclerosis (Fig. 35.2):

– Limited cutaneous SSc (lcSSc).

– Diffuse cutaneous SSc (dcSSc).

– SSc sine scleroderma (ssSSc).

Fig. 35.2 Clinical classification of systemic sclerosis (SSc). In addition to the three major clinical subsets shown here, two others are recognized: pre-SSc, in which the full extent of the patient’s skin sclerosis has not been reached; and overlap syndrome, in which either lcSSc or dcSSc coexists with another AI-CTD, e.g. polymyositis or SLE. CREST, calcinosis, Raynaud’s phenomenon, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, telangiectasias.

• Raynaud’s phenomenon (RP) is present in almost all SSc patients and is often the earliest presenting feature (Table 35.1; Figs. 35.3–35.5).

Table 35.1

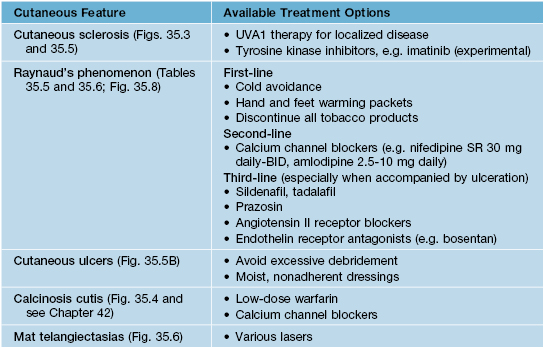

Common cutaneous features of systemic sclerosis and available treatment options.

UVA, ultraviolet A; BID, twice a day; SR, slow release.

Fig. 35.3 Pitted scars of the digital pulp in a patient with systemic sclerosis. Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

Fig. 35.5 Early versus late stages of systemic sclerosis (SSc) involving the hands. A Early edematous phase of SSc (note the demonstration of pitting edema on two of the digits). B Late stage of SSc with fixed flexion contractures, sclerodactyly, and digital ulceration overlying the third proximal interphalangeal joint. A, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD; B, Courtesy, M. Kari Connolly, MD.

Fig. 35.6 Mat (squared-off) telangiectasias in two patients with systemic sclerosis. The first patient (A) had limited cutaneous systemic sclerosis (lcSSc, formerly called CREST syndrome) while the second patient (B) presented with diffuse hyperpigmentation and had interstitial lung disease. A, Courtesy, M. Kari Connolly, MD; B, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD.

• Mat telangiectasias (Fig. 35.6) and proximal nailfold abnormalities (dilated capillary loops) are present in both lcSSc and dcSSc subtypes and are important clues to the Dx; additional common cutaneous findings are outlined in Table 35.1.

• Patients often have a characteristic facies with microstomia, retraction of the lips, perioral furrows, and a beaked nose; three types of dyspigmentation can also be seen, including diffuse hyperpigmentation and leukoderma of SSc (Fig. 35.7).

Fig. 35.7 The ‘salt and pepper’ sign. Leukoderma with retention of perifollicular pigmentation in a patient with systemic sclerosis.

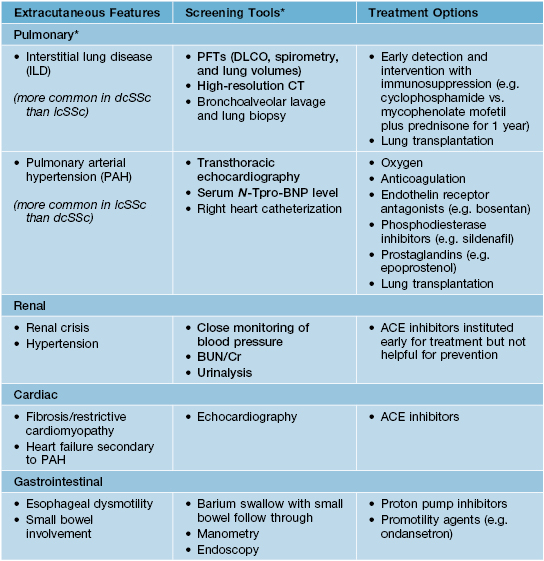

• In all three subtypes there can be internal organ involvement (Table 35.2), but patients with dcSSc are at increased risk for more clinically severe extracutaneous disease and overall worse outcomes.

Table 35.2

Extracutaneous features of systemic sclerosis and available screening and treatment options.

Items in bold signify those screening tests that are recommended at baseline in all newly diagnosed patients.

* Patients are typically asymptomatic in the early stages of ILD and PAH, which is when the diagnosis should be made and treatment instituted; cough, dyspnea on exertion, and shortness of breath are typical later-onset symptoms.

PFTs, pulmonary function tests; CT, computed tomography scan; DLCO, diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide; N-Tpro-BNP, N-terminal pro b-type natriuretic peptide; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Cr, creatinine; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme.

• Most patients (~98%) with SSc are ANA (+), usually in a speckled or nucleolar pattern; the presence of certain nucleolar antibodies is associated with characteristic clinical presentations (Table 35.3).

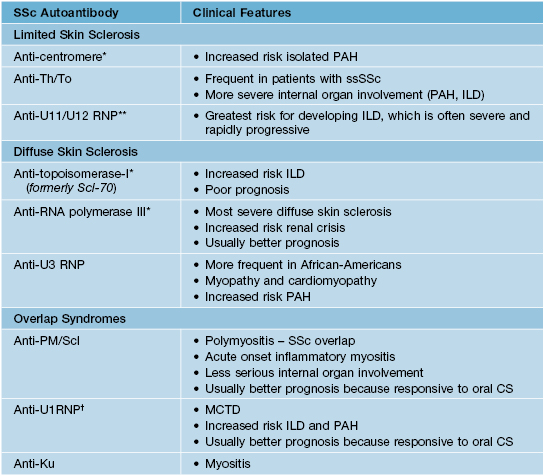

Table 35.3

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) autoantibody profile and its more frequently associated clinical presentation.

Although ~98% of SSc patients will have a (+) ANA, the diagnosis is still based on history and physical examination. The value of a (+) ANA lies in the subsequent identification of the patient’s SSc-specific autoantibody. More than 90% will have one of nine SSc autoantibodies. The nine autoantibodies are mostly mutually exclusive and tend not to change with time.

* The most frequently identified autoantibodies in systemic sclerosis patients.

** Currently not commercially available.

† The U1RNP antibody is specific for MCTD, which is often considered a distinct clinical entity (see Chapter 37).

PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; ILD, interstitial lung disease or pulmonary fibrosis; ssSSc, systemic sclerosis sine scleroderma; MCTD, mixed connective tissue disease.

• There are three phases of cutaneous disease:

– (1) Early edematous phase, featuring puffy hands and pitting edema of the digits (see Fig. 35.5A).

– (2) Indurated phase, characterized by hardening of the skin with taut and shiny appearance (see Fig. 35.5B).

– (3) Atrophic phase, with potential/gradual softening of the skin.

• All SSc patients should be screened and periodically monitored for internal organ involvement, especially lung and renal disease (Table 35.2).

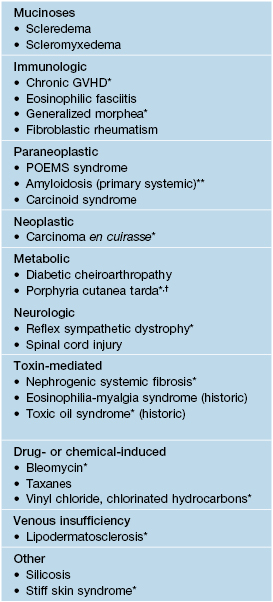

• DDx includes other sclerodermoid conditions (Table 35.4) and other AI-CTD (e.g. mixed connective tissue disease; see Chapter 37).

Table 35.4

Differential diagnosis of sclerodermoid conditions.

* Can overlap with morpheaform disorders, which are listed in Table 36.2.

** Primary cutaneous amyloidosis can also occur in patients with systemic sclerosis and generalized morphea.

† May also be observed in patients with congenital erythropoietic porphyria and hepatoerythropoietic porphyria.

GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; POEMS, polyneuropathy, organomegaly, endocrinopathy, monoclonal gammopathy, and skin changes.

• Recommendations for the initial evaluation of all patients with suspected SSc are presented in Table 35.2.

• Rx options for various cutaneous and extracutaneous features of SSc are outlined in Tables 35.1 and 35.2.

Raynaud’s Phenomenon

• Occurs in two settings: primary Raynaud’s phenomenon (Raynaud’s disease) and secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon (Table 35.5).

Table 35.5

Clinical and laboratory features of primary and secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon.

| Feature | Primary Raynaud’s | Secondary Raynaud’s |

| Sex | F : M 20 : 1 | F : M 4 : 1 |

| Age at onset | Puberty | >25 years |

| Frequency of attacks | Usually <5 per day | 5–10+ per day |

| Precipitants | Cold, emotional stress | Cold |

| Ischemic injury | Absent | Present |

| Abnormal capillaroscopy | Absent | >95% |

| Other vasomotor phenomena | Yes | Yes |

| Antinuclear antibodies | Absent/low titer | 90–95% |

| Anticentromere antibody | Absent | 50–60% |

| Anti-topoisomerase I (Scl-70) antibody | Absent | 20–30% |

| In vivo platelet activation | Absent | >75% |

Adapted from Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al. (Eds.). Rheumatology, 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2003. © Elsevier 2003.

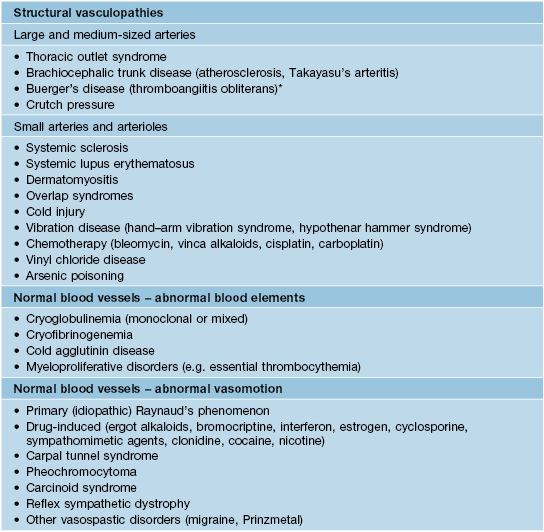

• Secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon is uncommon and is associated with an underlying medical problem (Table 35.6).

Table 35.6

Differential diagnosis of Raynaud’s phenomenon.

Paraneoplastic acral vascular syndrome, which can present with Raynaud’s phenomenon as well as acrocyanosis and gangrene, has been observed in patients with various solid tumors (e.g. lung or ovarian carcinoma).

* Can also affect small arteries.

Adapted from Hochberg MC, Silman AJ, Smolen JS, et al. (Eds.). Rheumatology, 3rd edn. Edinburgh: Mosby, 2003. © Elsevier 2003.

• SSc is one of the leading causes of secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon.

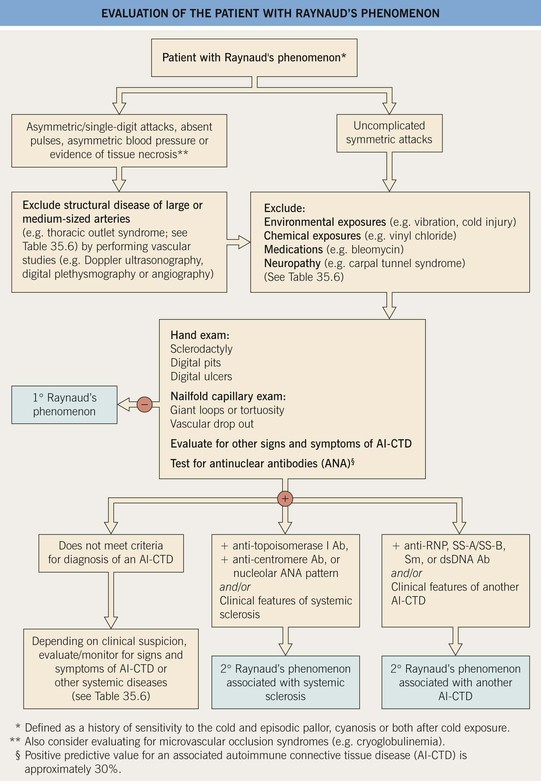

• An approach to differentiating primary from secondary Raynaud’s phenomenon is presented in Fig. 35.8.

Fig. 35.8 Evaluation of the patient with Raynaud’s phenomenon. RNP, ribonucleoprotein; Sm, Smith; ds, double-stranded.

• Rx: Table 35.1.

Sclerodermoid Disorders

• Disorders with a clinical presentation similar to SSc are referred to as ‘sclerodermoid disorders’ (Table 35.4).

Eosinophilic Fasciitis (Shulman’s Syndrome)

• May be one of the presentations of chronic GVHD; Dx by MRI or biopsy of involved fascia.

• Characterized initially by the rapid onset of edema and pain of the extremities, followed by symmetric, woody induration (spares hands, feet, face) (Fig. 35.9); associated with peripheral eosinophilia.

Fig. 35.9 Eosinophilic fasciitis. Induration of the skin with a dimpled or ‘pseudo-cellulite’ appearance, also referred to as rippling or puckering. Courtesy, Joyce Rico, MD.

Nephrogenic Systemic Fibrosis (NSF)

• Associated with exposure to gadolinium-based contrast medium.

• Presents on the extremities with symmetrically distributed, ill-defined, thick, indurated, erythematous to hyperpigmented plaques (Fig. 35.10).

Fig. 35.10 Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF). Thickening and induration of the skin can be obvious (A), or lesions may present as purple-brown plaques (B). C Scleral plaques in a patient younger than 45 years of age is a minor criterion for NSF. A, Courtesy, Jean L. Bolognia, MD; B, Courtesy, Kalman Watsky, MD.

• Confluence of lesions can result in joint contracture, pain, and loss of mobility.

• Systemic fibrosis affecting the heart, lungs, and skeletal muscles can also occur.