149 Sympathomimetics

• Sympathomimetic agents comprise a large collection of over-the-counter, prescription, and illicit drugs.

• The sympathomimetic toxicologic syndrome (toxidrome) is a constellation of signs and symptoms: elevated mood, psychomotor agitation, diaphoresis, tremor, hypertension, tachycardia, and mydriasis.

• The toxidrome can mimic hypoglycemia, withdrawal syndromes, and the anticholinergic toxidrome.

• Treatment is generally symptomatic and supportive and includes control of the patient’s psychomotor agitation. Occasionally, specific correction of the patient’s vital signs is necessary.

Epidemiology

A sympathomimetic agent is defined as any agent that may emulate the clinical effects of the endogenous sympathetic catecholamines epinephrine and norepinephrine. An exhaustive list of drugs falls into the class of sympathomimetics, ranging from over-the-counter and prescription agents to drugs of misuse and abuse (Box 149.1).

Box 149.1 Common Sympathomimetic Agents

In 2010, data released by the University of Michigan in their Monitoring the Future Survey demonstrated that cocaine use among high school students had declined since 2007.1 A difference in prevalence, which had decelerated, was noted. However, the year 2010 also saw a dramatic increase in the use of ecstasy, or 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA). Researchers believe that this shift may be the result of the adolescent population’s perception of a lower risk associated with MDMA.

Prescription agents continue to be a source of misuse. The rate of misuse of combination sympathomimetic products rose from 2009 to 2010. Overall, sympathomimetics remain a public health concern. According to the Drug Abuse Warning Network, these drugs accounted for almost 30% of all emergency department (ED) substance-related visits in 2009.2

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Methylxanthine exposure is virtually indistinguishable from β stimulation because of a shared final pathway, which increases intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate. Methylxanthines also result in increased circulating catecholamines and inhibit adenosine receptors. Potential clinical effects associated with sympathomimetics are listed in Box 149.2.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis of the patient with a sympathomimetic toxidrome is extensive (Box 149.3). It includes a spectrum of disease ranging from febrile illness to delirium.

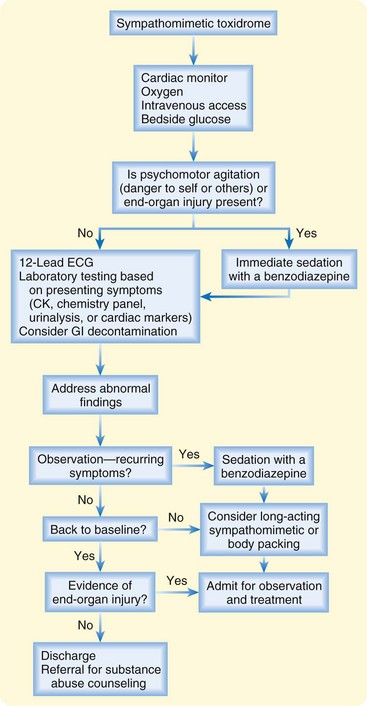

Most individuals who misuse or abuse sympathomimetics do not present to the ED; those who do are usually symptomatic. While the physician is considering the extensive differential diagnosis and clinical effects, aggressive measures should be taken to evaluate and stabilize these individuals (Fig. 149.1). Urine screening for sympathomimetics, with the exception of cocaine, is fraught with error and misinterpretation. A negative result does not exclude an exposure, whereas a positive result does not confirm causation of the patient’s clinical presentation. Therefore, this test is not recommended in the evaluation of a potentially poisoned adult patient.

Fig. 149.1 Treatment algorithm for sympathomimetic toxidrome.

CK, creatine kinase; ECG, electrocardiogram; GI, gastrointestinal.

Evaluation (Special Considerations)

Body Packers

The concealment of illicit substances within the gastrointestinal tract in large quantities requires close and careful evaluation. Individuals who take part in this trafficking, also known as body packers or “mules,” may be symptomatic or asymptomatic when they present to the ED. Those individuals with leaking or ruptured packets containing a sympathomimetic, often cocaine, need to be identified rapidly because they typically harbor enough drug to exceed multiple median lethal doses. Plain radiographs and oral contrast-enhanced CT scans of the abdomen have reasonable sensitivity in detecting packets; however, individuals already demonstrating signs and symptoms should receive an emergency surgical consultation with invasive removal of remaining packages.3 Body packers, if asymptomatic, require the same consideration, but they may necessitate a prolonged treatment course and monitoring.4

Treatment

Because of the large drug burden and the risk of packet leakage or rupture in body packers or “mules,” whole-bowel irrigation (WBI) can be used as first-line treatment in the asymptomatic patient. WBI can hasten the passage of packets through the gastrointestinal tract.5 This decontamination modality requires stringent dosing, averaging 2 L/hour of polyethylene glycol orally for an adult patient, with dose adjustments for the pediatric population. Most patients are unable to maintain this rate voluntarily and therefore require nasogastric tube placement. WBI is not without complications.6 Thus, consulting a toxicologist to discuss treatment is beneficial.

Mortality related to cocaine use has been associated with an elevation in core and ambient temperature.7 An ice bath that covers the largest surface area can quickly and effectively reduce core temperature. Other common modalities employed include mist and fan, as well as strategic anatomic application of ice packs (i.e., axilla and groin).

Special Considerations

Cocaine

Multiple agents are available to treat cocaine’s unique properties of vasoconstriction and sodium channel blockade. The first-line agent for treatment of cocaine toxicity is a benzodiazepine; however, some patients do not respond to this therapy. Ongoing vasoconstriction or vasospasm can be treated with an α-adrenergic receptor antagonist, such as phentolamine. In the setting of cocaine-associated acute coronary syndrome, β-adrenergic blockade is contraindicated despite the mortality benefit observed in patients with acute coronary syndrome unassociated with cocaine.8 The use of beta-blockers in cocaine toxicity is contraindicated because once the β-adrenergic receptor is blocked, these individuals suffer from unopposed α-adrenergic stimulation, thus worsening their clinical course. Even in the setting of suspected pure β-adrenergic agonist exposure, β-adrenergic blockade is rarely recommended because the underlying substrate usually depends on β- receptor agonism (i.e., asthmatic patients who overdose on albuterol).

Symptomatic cocaine body packers require urgent surgical removal of residual packets. In some instances, body packers are not symptomatic, and WBI can be initiated. In the event that packets cause a mechanical obstruction, endoscopic removal is a successful treatment modality.9

Vasopressors

Tips and Tricks

• The clinician should avoid neuroleptics (i.e., haloperidol) or antihistamines (i.e., diphenhydramine) to control the psychomotor agitation and psychosis associated with sympathomimetic overdose. Because neuroleptics have anticholinergic properties, decrease seizure thresholds, and increase QT intervals, these agents are a poor choice to achieve sedation. Anticholinergic toxicity is within the diagnostic consideration of the undifferentiated agitated delirium, such that administration of an anticholinergic agent may be additive to potential morbidity. Benzodiazepines are the preferred choice for sedation.

• The only situation in which fluid resuscitation should not be initiated before laboratory evaluation is in the individual suspected to have syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone from 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine use.

• Because of persistent tachycardia and extrapolating data from acute coronary syndromes, emergency physicians often feel compelled to rate-control these patients with β-adrenergic receptor antagonists. Potential unopposed α-adrenergic agonism may lead to a hypertensive crisis, and these agents therefore should be avoided in the undifferentiated sympathomimetic toxidrome.

• Amiodarone is listed as a first-line agent in the treatment of wide complex tachycardia. Concern exists about the intrinsic β-adrenergic receptor antagonist properties of amiodarone, for the reasons stated. Amiodarone should not be used in the setting of cocaine toxicity because of this theoretical risk.

Disposition

The evaluation and treatment of cocaine-associated chest pain have evolved and have regional variation. A short observation period with serial ECGs and serial cardiac-specific markers performed 6 to 8 hours apart can be used to exclude cocaine-associated myocardial infarction.10 Despite excluding the diagnosis of myocardial infarction, all patients should have urgent outpatient evaluation for coronary artery disease and drug abuse counseling.

![]() Red Flags

Red Flags

• Widened pulse pressure and hypokalemia, if present, may suggest exposure to either a methylxanthine or a β-adrenergic receptor agonist.

• A unique property of cocaine is its ability to block myocardial sodium channels, manifested as a widened QRS complex on the electrocardiogram. These electrophysiologic effects are indistinguishable from those of other class I antidysrhythmics and require immediate attention and reversal.

• Sympathomimetic stimulation of the central nervous system that results in psychomotor agitation and hyperthermia is associated with increased mortality and should be aggressively treated.

• Psychomotor agitation can result in rhabdomyolysis, tremor, and muscle rigidity. If left undetected, severe rhabdomyolysis may cause renal insufficiency or failure.

• The clinician should suspect a body packer when symptoms recur or are prolonged and when an individual develops signs and symptoms of sympathomimetic exposure associated with an international flight.

• Individuals already demonstrating signs and symptoms of packet leakage or rupture should receive an urgent surgical consultation and invasive removal of remaining packages because the lethality of the drug is high.

de Prost N, Lefebvre A, Questel F, et al. Prognosis of cocaine body-packers. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:955–958.

Lange RA, Cigarroa RG, Flores ED, et al. Potentiation of cocaine-induced coronary vasoconstriction by beta-adrenergic blockade. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:897–903.

Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, Leon AC, et al. Ambient temperature and mortality from unintentional cocaine overdose. JAMA. 1998;279:1795–1800.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Monitoring the future survey. Available at http://www.nida.nih.gov/DrugPages/Stats.html, 2012. Accessed February 7

Traub SJ, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS. Body packing: the internal concealment of illicit drugs. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2519–2526.

Weber JE, Shofer FS, Larkin GL, et al. Validation of a brief observation period for patients with cocaine-associated chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:510–517.

1 National Institute on Drug Abuse. Monitoring the future survey. http://www.nida.nih.gov/DrugPages/Stats.html.

2 Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Drug abuse warning network. http://www.samhsa.gov/data/2k11/DAWN/2k9DAWNED/HTML/DAWN2k9ED.htm, 2009.

3 Traub SJ, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS. Body packing: the internal concealment of illicit drugs. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2519–2526.

4 de Prost N, Lefebvre A, Questel F, et al. Prognosis of cocaine body-packers. Intensive Care Med. 2005;31:955–958.

5 Pidoto RR, Agliata AM, Bertolini R, et al. A new method of packaging cocaine for international traffic and implications for the management of cocaine body packers. J Emerg Med. 2002;23:149–153.

6 Makosiej FJ, Hoffman RS, Howland MA, Goldfrank LR. An in vitro evaluation of cocaine hydrochloride adsorption by activated charcoal and desorption upon addition of polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1993;31:381–395.

7 Marzuk PM, Tardiff K, Leon AC, et al. Ambient temperature and mortality from unintentional cocaine overdose. JAMA. 1998;279:1795–1800.

8 Lange RA, Cigarroa RG, Flores ED, et al. Potentiation of cocaine-induced coronary vasoconstriction by beta-adrenergic blockade. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:897–903.

9 Silverberg D, Menes T, Kim U. Surgery for “body packers”: a 15-year experience. World J Surg. 2006;30:541–546.

10 Weber JE, Shofer FS, Larkin GL, et al. Validation of a brief observation period for patients with cocaine-associated chest pain. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:510–517.