CHAPTER 89 Surgical Treatment of Major Depression

Depression is a prevalent and often debilitating psychiatric disorder with a 6-month prevalence of approximately 5%.1 In the United States alone, approximately 20 million people have been diagnosed with depression at some point in their lives. Depression accounts for the greatest number of missed workdays due to illness, with an estimated economic burden of approximately $40 billion per year.2

The initial therapeutic approach for patients with depression consists of medication or psychotherapy, or both. For patients who do not respond, suitable alternatives include other medications from the same or different drug classes, augmentative pharmacologic regimens, a combination of antidepressant agents from different classes, and eventually electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). The main objectives of treatment are the remission of symptoms, restoration of daily function, and prevention of relapse and recurrence. It is estimated that only 60% to 70% of patients respond favorably to initial treatment. More important, failure to respond to any initial treatment predicts a poor response to future treatments (including ECT) and a higher likelihood of relapse.3,4 Consequently, up to 40% of patients (1.5% of the general population) have chronic and refractory forms of depression. Up to 15% of patients with severe depression require hospitalization and eventually commit suicide.5,6 Therefore, for this refractory population, surgery may be considered part of the therapeutic armamentarium.

History of Psychosurgery

The history of neurosurgical intervention for psychiatric illness may be as old as the history of neurosurgery itself. The record of trephination to remove parts of the skull dates from as early as 10,000 BC.7 This procedure was apparently common and widespread, with more than 1500 specimens discovered from Europe, Asia, Africa, North America, Central America, South America, and Oceania.8,9 Although the exact purposes of such trephinations are disputed, some were clearly motivated by magicotherapeutic goals, with psychiatric illnesses mistakenly thought to arise from demonic possession.10 Written records of trephining for the “relief of unexplained and unbearable pain … melancholia … or to release demons” have been dated as early as 1500 BC.11

The literature of the late 19th and early 20th centuries is peppered with a few reports of neurosurgical interventions for psychiatric illness. In 1891, Gottlieb Burckhardt performed bilateral cortical resections (topectomies) in six patients institutionalized for pathologic behavior. Five survived the surgery, and although they remained psychotic, they were considered to be more placid.12,13 Burckhardt received significant criticism after the report and abandoned the procedure. In 1910, Ludwig Puusepp reported on the severing of fibers running from the frontal to the parietal lobes in three “bipolar” patients, but he ultimately considered these to be surgical failures. Fourteen other patients who underwent frontal leucotomy were relieved of their aggressive symptoms.14 Studies by Dandy,15 Penfield,16 and Bailey17 documented how the treatment of neurosurgical diseases such as tumors and abscesses relieved mental symptoms of anxiety and depression and provided insight into the potential cerebral localization of such problems. In 1933, John Fulton and Carlyle Jacobsen operated on chimpanzees that had been trained to perform various tasks. Before the surgeries, the animals were noted to have severe “frustrational behavior” when they were not rewarded after performing their tasks poorly. After unilateral frontal lobectomies, no significant changes in behavior or temperament were noticed.18 When the procedures were done bilaterally, however, the animals displayed little agitation or concern about making poor choices on the learned tasks or the lack of reward for completion of the tasks (although general behavior was not thought to have changed). Fulton presented the data in 1935 at the International Neurologic Conference in London,19 which was attended by Egaz Moniz, a neurologist from Portugal. Inspired by Fulton’s experiments, Moniz introduced the prefrontal leucotomy (later renamed lobotomy) later that year.20 The initial operations, performed with his colleague Almeida Lima, involved alcohol injections into the centrum semiovale, with the goal of disrupting frontal projections to and from the thalamus; however, because of the need to increase the number of injections and a lack of control owing to leakage of alcohol along the needle track, the authors switched to the leucotome by their ninth procedure.21

Also in the audience at Fulton’s presentation was American neurologist Walter Freeman. At the time, psychiatric illness was exacting a staggering toll in the United States. The estimated financial burden of psychiatric illness was $1.5 billion a year, with 450,000 patients living in asylums.22,23 The results of Freeman’s early experimentation with lobotomy, performed in collaboration with neurosurgeon James Watts, were mixed. Freeman thought the Moniz procedure was inadequate, but initial attempts at a deeper lesion resulted in complications and fatalities.24 Freeman continued to modify the procedure, employing x-ray and skull landmarks in an attempt to better define the appropriate target. He yearned to make the procedure safer and easier and to eliminate the need for anesthesia, the operating room, and the surgeon.25 Consequently, in 1946 Freeman introduced the transorbital lobotomy, first described by Amarro Fiamberti, to the United States. He believed this procedure would realize his dream and make lobotomy more accessible to the mentally ill. During this procedure, which Freeman performed in the outpatient setting, the patient was anesthetized via electroconvulsion. An ice pick was then driven with a mallet through the orbital roof and swept in a specific fashion and direction to sever the desired tracts. Freeman performed or supervised 4000 transorbital lobotomies before the procedure fell out of favor.26,27 It is estimated that between 1945 and 1955, 50,000 lobotomies were performed in the United States.19,23

More-Selective Lesioning Techniques

Orbitofrontal Cortex

As early as the 1930s, it was realized that lesions closer to the orbital and inferior aspects of the frontal lobes produced changes in emotional tone, whereas lesions involving the superolateral aspects of the frontal lobe were associated with intellectual disturbance.28 In addition, stimulation of the orbitofrontal and medial prefrontal cortices was soon recognized to produce autonomic responses. These responses were thought to be predictors of the response to ablation because the ablation of corresponding regions in animals induced tranquility and loss of fear. Based on these findings, Scoville proposed the undercutting of the orbitofrontal cortex as a surgical therapy for psychiatric disorders.29–33 The procedure involved sectioning the brain parenchyma in a plane parallel to and approximately 1 cm dorsal to the orbital surface. The anteroposterior extent of the undercutting was dictated by the distance between the rostral portion of the frontal lobe and the point of emergence of the optic nerve from the optic foramen.34 The cut was extended medially until the midline was nearly reached and laterally until increased resistance indicated that the lateral cranial wall was being approached.34 Patients with depression and obsessive features responded best to this procedure.29–34 Of considerable importance, adverse effects were not significant when compared with those associated with leucotomy. No intellectual deterioration was noted, and there was only minor, transient blunting of personality; however, some loss of spontaneity (which did not usually culminate in apathy) and transient postoperative confusion were often reported.29–34

Subsequently, Knight modified the surgery by omitting the lateral portion of the cut, confining the incision to an arc about 2.5 cm wide, passing back to the inner aspect of the frontal lobe beneath the anterior horn of the lateral ventricle.35 As with other orbitofrontal undercutting procedures, patients with depression and anxiety experienced good outcomes.35 Approximately 80% to 90% of patients with depression treated with selective orbitofrontal undercutting were said to respond to some extent.35

Superior Convexity of the Frontal Cortex

In contrast to orbitofrontal undercutting, selective lesions of the superior convexity of the frontal cortex were performed mainly in patients with paraphrenia and severe psychotic disorders, including schizophrenia.36,37 This technique was eventually abandoned owing to poor clinical results.

Medial Prefrontal Cortex

Lesions of medial prefrontal cortical structures were also attempted for the treatment of psychiatric disorders. These focused mainly on the cingulate gyrus, with the goal of disconnecting the frontal lobes from the limbic system (a more extensive rationale for the development of cingulotomy is described later). Surgery was initially performed as an open procedure, with direct visualization of the medial prefrontal cortical structures. The main goal of cingulotractotomies and subrostral cingulotomies was to lesion the portion of the cingulate gyrus ventral to the genu and rostrum of the corpus callosum.38,39 Seventy percent to 80% of patients with depression were reported to respond favorably to this procedure. The rostral portion of the knee of the corpus callosum or the adjacent cingulate gyrus was also targeted39,40; however, this so-called mesoloviotomy was not as effective as subrostral cingulotomy for alleviating the symptoms of depression.39

Current Stereotactic Techniques

The development of a stereotactic frame for human use in 1947 ushered in the modern era of stereotactic neurosurgery, allowing surgeons to lesion the brain in a safer and more controlled fashion. Spiegel and colleagues41 were the first to apply stereotactic techniques and reported promising results when lesions of the medial thalamic region were carried out to reduce emotional reactivity in psychiatric patients. Since then a variety of deep brain structures have been targeted to treat psychiatric illness. A review of the most successful of these procedures follows.

Subcaudate Tractotomy

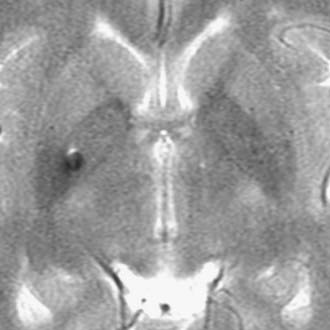

In 1955, Knight reported his preliminary experience with selective undercutting of the orbitofrontal cortex for the treatment of psychiatric disorders.35 In subsequent articles it was postulated that the outcome of the procedure, later named subcaudate tractotomy, derived from the disruption of fibers interconnecting the frontal lobe, substantia innominata, amygdala, and hypothalamus.42–44 In fact, the general belief was that lesions would more specifically compromise fibers adjacent to area 13 (and to some extent area 14) and the substantia innominata (Fig. 89-1).

A significant problem with the freehand lesioning approach is its inherent imprecision.45 Consequently, in the 1960s Knight began to perform subcaudate tractotomy using stereotactic techniques. At first, lesions were created with radioactive yttrium.44 Between three and five rods were implanted per hemisphere, creating lesions that measured roughly 20 × 20 × 5 mm. Based on Knight’s early reports, patients with depression responded particularly well to the procedure, compared with patients with schizophrenia and personality disorders.43,46–53 Overall, 34% to 50% of patients had a good outcome, with or without minimal residual symptoms. In addition, 17% to 32% of patients showed some degree of improvement but had persistent symptoms that needed treatment.46,47,51,52 Of interest, the improvement after subcaudate tractotomy seemed to occur over weeks to months.46 Medications were reduced and discontinued whenever possible. In the 1990s, thermocontrolled electrocoagulation replaced yttrium as the preferred means of creating lesions, with comparable results reported.46,53

Complications of subcaudate tractotomy include confusion in the early postoperative period (usually the first day after surgery), with disorientation seen in 10% of the patients.46,47 Seizures occur in 1% to 2%. The postoperative suicide rate is approximately 1%. In the early postoperative period, neuropsychological tests demonstrate decay in recognition memory tests and a marked tendency to confabulate during recall memory tasks.54 Fortunately, these deficits appear to be transient, with no lasting effects at long-term follow-up.

Cingulotomy

The rationale for the development of cingulotomy derives from the hypothesis that the Papez circuit is of primary importance in mediating inward emotional experience and outward emotional expression.55 Because the interruption of cingulate fibers in nonhuman primates induces a state of “tameness and placidity,” it was suggested that cingulotomy could be used to treat patients with psychiatric symptoms.56–59

Cingulotomy has been extensively explored since the 1950s. The procedure has been used mainly for the treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), so few patients with depression have been reported in the literature.60–65 In their first studies of cingulotomy at the Massachusetts General Hospital, Ballantine and colleagues62,63 reported very good outcomes in patients with MDD. In a recent study from the same center, Shields and colleagues66 reported on 33 patients with MDD who underwent one or more ablative procedures. Each of the subjects was initially treated with cingulotomy. A response to surgery was defined as a 50% reduction in the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) score and a Clinical Global Improvement (CGI) score of less than 2. Patients who did not achieve a 35% improvement in the BDI and did not have a CGI of 2 or less were considered nonresponders and were deemed candidates for additional surgical procedures. Overall, 17 patients (52%) underwent single cingulotomies, 9 (27%) repeated cingulotomies, and 7 (21%) limbic leucotomies. Of the patients treated with one cingulotomy, 41% were considered to be responders and 35% were partial responders. Of the patients treated with multiple lesions, 25% were responders and 50% were partial responders.66 The outcomes for multiple cingulotomies versus cingulotomy followed by limbic leucotomy were not compared.

The usual target for cingulotomy is the dorsal aspect of the anterior cingulate gyrus (Brodmann’s area [BA] 24), 2 to 4 cm posterior to the anterior aspect of the frontal horn (see Fig. 89-1).61,62,66–68 The correlation between clinical outcome and lesion location was recently investigated in patients with MDD by Steele and colleagues.68 They suggested that the more anterior the lesion within the usually targeted anterior cingulate cortex region, the better the outcome as assessed by the Montgomery Asberg Depression Scale (MADRS) and the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAMD). The optimal lesion volume was 1000 to 2000 mm3.

The most commonly reported side effects of cingulotomy are a 1% to 2% risk of seizures and a less than 5% risk of transient urinary incontinence.60,61,63,64,69

Limbic Leucotomy

Most surgeons perform two to three lesions in the anteromedial frontal lobe beneath the caudate nucleus and two to four lesions in the cingulate gyrus (BA 24).70–78 In older series, 80% of patients with depression treated with limbic leucotomy were considered to benefit from surgery, half being symptom free or much improved.70–75 The mean HAMD score was improved 51%.74 The main side effects include postoperative confusion, seizures, and incontinence.

In a more recent study, six patients with MDD were treated with limbic leucotomy, either as a first procedure or after unsuccessful cingulotomy.76 In that trial, 50% of patients were considered to be responders based on physicians’ rated assessments. In addition, 40% of patients who had both pre- and postoperative BDI scores were classified as responders. One depressed patient with a history of suicidal ideation and many serious attempts committed suicide after the procedure. Other side effects were similar to those described in earlier series, including transient somnolence and apathy (25% to 30%), postoperative seizures (19%), and bladder incontinence (mostly transient; 24%). These outcomes have been corroborated in a larger clinical series.66

Capsulotomy

The goal of capsulotomy is to disrupt the frontothalamic fiber systems running in the anterior limb of the internal capsule (see Fig. 89-1). Some of the projections believed to be important extend from the prefrontal cortex and substantia innominata to the hypothalamus.79 Capsulotomy has been used predominantly to treat anxiety and OCD.79–82

Deep Brain Stimulation

DBS has been used extensively for the treatment of movement disorders and pain.83–90 In addition, DBS has been investigated as a potential therapy for minimally conscious states,91 aggressiveness,92 cluster headaches,93,94 obesity,95 memory modulation,95 and psychiatric disorders, including OCD96–101 and major depression. DBS targets proposed for the surgical treatment of depression are the subgenual cingulum (BA 25), inferior thalamic peduncle, and nucleus accumbens–anterior limb of the internal capsule. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) is also used for the treatment of depression. Although VNS does not involve the stimulation of deep brain structures per se, VNS is discussed in this section as a surgical method of neuromodulation for depression.

Subcallosal Cingulate Gyrus

The rationale for targeting the subcallosal cingulate gyrus (SCG), including BA 25, for the treatment of depression derives mainly from functional imaging studies of depressed patients. Blood flow to BA 25 increases in healthy subjects who are asked to rehearse autobiographic scripts of sad events or when previously depressed subjects show a return of depressive symptoms following rapid tryptophan depletion (for a review, see reference 102). In patients with depression, baseline metabolic activity is increased in BA 25 and decreased in BA 46 and BA 9.103 After treatment with antidepressants, behavioral therapy, or ECT, this pattern is reversed, with a reduction of activity in BA 25 and an increase in BA 46 and BA 9.103,104 Based on these findings, Mayberg and colleagues105–107 suggested that increased activity in BA 25 and decreased activity in BA 46 and BA 9 could be important mechanisms in the pathophysiology of depression and that pathways connecting the subgenual cingulum and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex could mediate interactions between mood and attention for the maintenance of emotional homeostasis in health and disease. DBS surgery was proposed as a means to modulate BA 25 activity in patients with refractory depression.

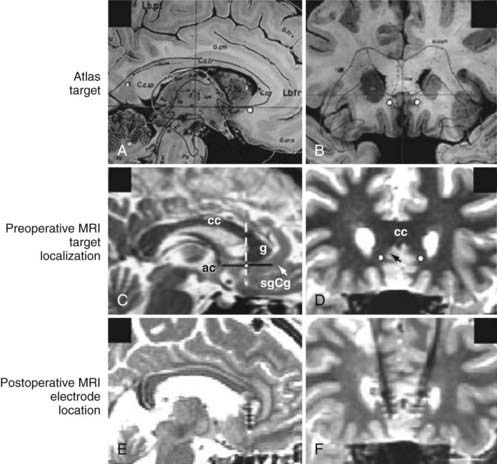

The surgical procedure for implanting SCG electrodes in our institution is similar to that used for other conditions. A Leksell frame (Elekta Instruments) is applied to the patient’s head under local anesthesia, and stereotactic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is performed. Initially, the subgenual cingulate region is identified on reconstructed sagittal images (Fig. 89-2). This often corresponds to a coronal section in which the initial aspect of the anterior horns of the lateral ventricles can be visualized (see Fig. 89-2). In the mediolateral plane, the selected target is the transition between gray and white matter of the SCG. Microelectrode recording is not essential to perform this procedure, but we use it to help localize the junction of gray and white matter at the superior and inferior banks of the SCG cortex. Once this physiologic region is determined, DBS quadripolar electrodes are implanted in the target region (see Fig. 89-2). In the initial series, some patients exhibited dramatic responses to macrostimulation in the operating room, including a sudden sense of calm and peacefulness; changes in interest, motivation, and curiosity; increased perception of colors; and improvements in psychomotor speed.104 We no longer perform such tests, however, because these effects are not predictive of a good postoperative outcome, and patients who do not experience these intraoperative effects benefit equally from the procedure. Once the leads are inserted and secured, the head frame is removed and a pulse generator is implanted in the right subclavicular region with the patient under general anesthesia. In our center, the position of the electrodes is confirmed by postoperative MRI (see Fig. 89-2).

We considered a 50% improvement in the HAMD-17 score to be a clinically significant response. Twelve months after surgery, 11 of 20 patients (55%) had responded positively to DBS, and 35% achieved or were within one point of remission, defined as an HAMD-17 score less than 8.103 We have now operated on 30 patients, and these overall results have been sustained (some patients now have 3 to 4 years of follow-up). Twelve months after DBS, all subscores of the HAMD scale, including mood, anxiety, sleep, and somatic symptoms, were significantly improved.103 The most common stimulation parameters used are as follows: amplitude of 3 to 4 V, pulse width of 60 µsec, and frequency of 130 Hz. Our results have now been replicated in a multicenter study involving 20 patients at three Canadian sites.108

Side effects of SCG-DBS in our center were related mainly to the surgical procedure or hardware implants and were similar to those observed with DBS at other targets (e.g., hardware infection, pain at the IPG site).103,104 Neuropsychological assessment 12 months after stimulation onset did not reveal any adverse effects.109

Pretreatment positron emission tomography scanning in our patient series revealed increased activity in the SCG and decreased activity in the prefrontal and premotor cortices, dorsal anterior cingulate gyrus, and anterior insula (compared with nondepressed control subjects). This pattern was reversed after 3 months of chronic stimulation in patients who improved with DBS.104

Finally, we reported on a patient with MDD who initially underwent anterior cingulotomy with a marked 77% reduction in her HAMD-17 score.110 Approximately 6 months after surgery, her depression recurred and she was offered SCG-DBS. With stimulation, she exhibited a 68% reduction in HAMD score, which has been sustained for more than 30 months. This case suggests that DBS may be a promising alternative to repeated cingulotomies or subcaudate tractotomies in patients with MDD who fail more traditional ablative surgery.

Inferior Thalamic Peduncle

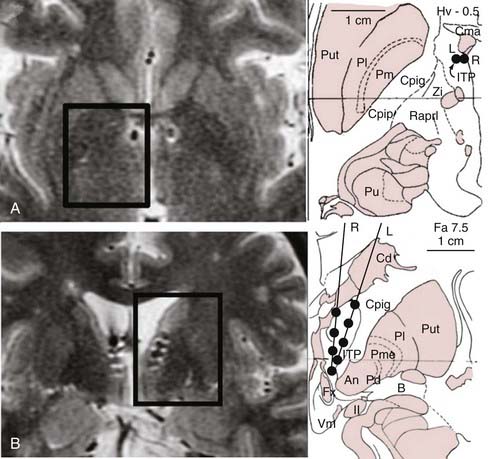

The rationale for targeting the inferior thalamic peduncle in depression is that this bundle constitutes a system of fibers conveying projections from intralaminar and midline thalamic nuclei to the orbitofrontal cortex.111–113 Only one patient with treatment-refractory depression who was treated with this technique has been reported in the literature.111 Initially, eight-contact electrodes were placed into the target area so that contacts 1 and 2 were in the ventromedial hypothalamus, contacts 3 and 4 were adjacent to the fornix, contacts 5 and 6 were in the vicinity of the inferior thalamic peduncle, and contacts 7 and 8 were within the region of the nucleus reticularis polaris (Fig. 89-3). Bipolar stimulation through the ventral contacts (1-2; 2-3) induced vertical nystagmus, anxiety, and autonomic dysfunction, including an increase in heart rate and blood pressure. Stimulation through the other electrode contacts did not result in adverse effects. The test electrodes were then replaced with quadripolar electrodes for chronic stimulation.

Nucleus Accumbens

The rationale for DBS at the ventral striatum (or, more specifically, in the nucleus accumbens) is based on three lines of evidence: (1) this region is implicated in mechanisms of reward, (2) it acts as a “motivation gateway” between limbic systems involved in emotion and systems involved in motor control, and (3) the ventral striatum is in a unique location to modulate the activity of other brain regions involved in mechanisms of depression.114

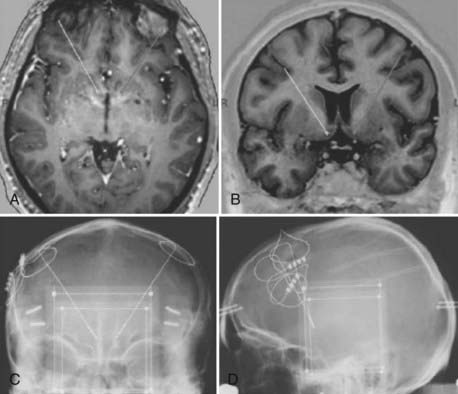

At present, only short-term follow-up of three patients with DBS at the ventral striatum has been reported in the literature. Each patient had severe MDD; had HAMD-24 scores of 38, 31, and 32, respectively; and was refractory to multiple drugs, augmentation therapy, and ECT. The electrodes were implanted so that the distal contacts were in the core and shell of the accumbens (Fig. 89-4). Patients could not tell whether the device was on or off, but some reported an increase in reward-seeking motivation during stimulation (e.g., one patient wanted to travel to another city).

In addition to clinical outcome, positron emission tomography studies were conducted at baseline and after 1 week of stimulation. The authors reported an increase in metabolic activity within the nucleus accumbens, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and amygdala and decreased activity in the medial prefrontal cortex and caudate nucleus during stimulation.114

Anterior Capsule

The rationale for anterior capsule stimulation to treat depression is based on improvements in mood observed in patients with OCD who were treated with DBS in this region.98,100,101 In addition, the anterior capsule has been used as a target for lesions (capsulotomy) for decades, primarily to treat OCD (see Fig. 89-1). In a recent clinical trial, 15 patients with refractory depression were treated with DBS in the region of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum in an open-label study at three clinical sites.115 At 6 months, 40% to 47% of patients were considered to be responders and 20% to 27% remitters (depending on whether they were assessed with the HAMD-24 or the Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale [MADRS]). A similar outcome was reported at 1 year and during the last follow-up appointment (up to 4 years). Reduction in HAMD-24 scores at 6 months was in the order of 47%. Overall, surgery was well tolerated with a profile of complications similar to that in other targets. No neuropsychological deleterious effects were reported.115

Vagus Nerve Stimulation

The rationale for stimulating the vagus nerve to treat depression stems from several previous findings.116 First, VNS alters the cerebrospinal fluid concentration of neurotransmitters implicated in the neurophysiology of depression, including norepinephrine and serotonin.117–119 Second, VNS alters the functional connectivity of central nervous system regions that are dysregulated in mood disorders, including the orbitofrontal cortex, insula, thalamus, hypothalamus, cingulate cortex, and hippocampus.120,121 Finally, patients with epilepsy receiving VNS have exhibited improvement in depressive symptoms, independent of seizure control.122,123

In most VNS trials, inclusion criteria were as follows: HAMD-24 or HAMD-28 scores greater than 20, a current MDE lasting at least 2 years or a history of at least four MDEs, and failure to respond to at least two adequate trials of different classes of medications.116,124–127

In the first open-label study, 30 patients were operated on, and the outcome after 10 weeks of stimulation was reported. Forty percent of the subjects were considered to be responders (i.e., HAMD scores reduced by 50% or more).116 Stimulation parameters used in the trial were 20 Hz, 500 µsec, and a median current of 0.75 mA, with the device turned on for 30 seconds and off for 5 minutes. One year after surgery, 28 of the patients were reassessed, and a slight increase in the number of responders (46%) was observed.128 Twenty-nine percent were considered to be in remission, with HAMD scores less than 10. The most common side effects at 3 months were voice changes (53%), cough (13%), dyspnea (17%), and neck pain (17%)116; however, these were significantly reduced after 1 year of stimulation (voice changes, 21%; cough, 0%; dyspnea, 7%; neck pain, 7%). No neurocognitive deficits were seen with VNS therapy, as assessed by a neuropsychological battery.129

In a second series of publications, the outcomes of 60 patients treated as part of an extended open-label study were reported. This study included the original 30 patients plus an additional 30.127 In contrast to the previous study, only 30.5% of the patients were classified as responders after 10 weeks of stimulation; however, at 12 and 24 months, the response rates were 42% and 44%, and the remission rates were 22% and 27%, respectively.127 In addition to the adverse effects noted in the initial trial, the authors reported that some patients experienced a worsening of depression and hypomanic-manic episodes, and some committed suicide.124 The relationship of these events to stimulation was unclear, particularly given the inclusion of patients with bipolar disorder.

Because these two sets of series were conducted by the same centers, the authors attempted to isolate potential factors that might have been responsible for the worse outcome in the extended trial. In the latter series, they found a recruitment bias toward a single center that selected candidates who were more resistant to antidepressant treatments (more patients had failed ECT, and a significantly higher number of medication trials had been attempted).125,126,130 The authors noted that patients with fewer antidepressant treatment trials might have a higher response to VNS.125

Based on the results of these open-label trials, three multicenter, placebo-controlled, industry-sponsored trials were conducted.126 In the first trial, a blinded assessment was conducted with patients receiving VNS or sham stimulation for 10 weeks.126 No significant differences were observed between the sham and treatment groups in most of the scores assessed, including the HAMD and MADRS. Overall, 15.2% of the patients in the treatment group and 10% in the control group responded to treatment. The only score that was significantly improved in the treatment group was the inventory of depressive symptomatology self-report. After the 10th week of blinded treatment, patients received open-label stimulation for 1 year. Medication changes and ECT were also allowed during this phase.130 At the end of this 1-year period, 29.8% of patients were considered to be responders and 17.1% remitters (27.2% and 15.8%, respectively, if one considers the last observation carried forward).124–126130 As with the initial trials, the number of responders increased with time. Adverse events in these trials were similar to those in the initial reports. Unfortunately, the study design precluded a clear attribution of clinical response to VNS because it allowed medication changes and the addition of other treatments such as ECT.

The third study of the series was a comparison of the outcome of patients receiving VNS for 12 months with a cohort of patients receiving only medical treatment.131 Although the percentage of responders in the group treated with VNS plus medical therapy was significantly higher (30% versus 13% in patients receiving medical therapy only), this sort of comparison has several biases, including a potential placebo response and a lack of randomization.

George MS, Rush AJ, Marangell LB, et al. A one-year comparison of vagus nerve stimulation with treatment as usual for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:364-373.

Hodgkiss AD, Malizia AL, Bartlett JR, Bridges PK. Outcome after the psychosurgical operation of stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy, 1979-1991. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7:230-234.

Jimenez F, Velasco F, Salin-Pascual R, et al. A patient with a resistant major depression disorder treated with deep brain stimulation in the inferior thalamic peduncle. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:585-593.

Kopell BH, Rezai AR. Psychiatric neurosurgery: a historical perspective. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:181-197.

Lozano AM, Mayberg HS, Giacobbe P, et al. Subcallosal cingulate gyrus deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:461-467.

Malone DAJr, Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:267-275.

Mashour GA, Walker EE, Martuza RL. Psychosurgery: past, present, and future. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:409-419.

Mayberg HS. Limbic-cortical dysregulation: a proposed model of depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9:471-481.

Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45:651-660.

Montoya A, Weiss AP, Price BH, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided stereotactic limbic leukotomy for treatment of intractable psychiatric disease. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:1043-1049.

Nahas Z, Marangell LB, Husain MM, et al. Two-year outcome of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment of major depressive episodes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1097-1104.

Richter EO, Davis KD, Hamani C, et al. Cingulotomy for psychiatric disease: microelectrode guidance, a callosal reference system for documenting lesion location, and clinical results. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:622-628.

Rush AJ, George MS, Sackeim HA, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant depressions: a multicenter study. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:276-286.

Rush AJ, Marangell LB, Sackeim HA, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a randomized, controlled acute phase trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:347-354.

Rush AJ, Sackeim HA, Marangell LB, et al. Effects of 12 months of vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression: a naturalistic study. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:355-363.

Sackeim HA, Rush AJ, George MS, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant depression: efficacy, side effects, and predictors of outcome. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:713-728.

Schlaepfer TE, Cohen MX, Frick C, et al. Deep brain stimulation to reward circuitry alleviates anhedonia in refractory major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:368-377.

Shields DC, Asaad W, Eskandar EN, et al. Prospective assessment of stereotactic ablative surgery for intractable major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:449-454.

Steele JD, Christmas D, Eljamel MS, Matthews K. Anterior cingulotomy for major depression: clinical outcome and relationship to lesion characteristics. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:670-677.

1 Depression Guideline Panel. Depression in Primary Care: Volume 1 Detection and Diagnosis. Rockville, MD: US, Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. 1993.

2 Greenberg PE, Stiglin LE, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER. The economic burden of depression in 1990. J Clin Psychiatry. 1993;54:405-418.

3 Prudic J, Haskett RF, Mulsant B, et al. Resistance to antidepressant medications and short-term clinical response to ECT. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:985-992.

4 Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Acute and longer-term outcomes in depressed outpatients requiring one or several treatment steps: a STAR*D report. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1905-1917.

5 Depression Guideline Panel. Depression in Primary Care: Volume 2 Treatment of Major Depression. Rockville, MD: US, Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. 1993.

6 Guze SB, Robins E. Suicide and primary affective disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 1970;117:437-438.

7 Saul F, Saul J. Trepanation: Old World and New World. In: Greenblatt S, editor. History of Neurosurgery in Its Scientific and Professional Contexts. Park Ridge, Ill: AANS; 1997:29-35.

8 Lisowski F. Prehistoric and early historic trepanation. In: Brothwell D, Sandison A, editors. Diseases in Antiquity. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas; 1967:651-672.

9 Liu CY, Apuzzo ML. The genesis of neurosurgery and the evolution of the neurosurgical operative environment: part I—prehistory to 2003. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:3-19.

10 Heller AC, Amar AP, Liu CY, Apuzzo ML. Surgery of the mind and mood: a mosaic of issues in time and evolution. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:720-733.

11 Horrax G. Neurosurgery: An Historical Sketch. Springfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas; 1952.

12 Burckhardt G. On cortical resection as a contribution to the operative treatment of psychosis. Z Psychiatrie psychischgerichtliche Medizin. 1891;47:463-548.

13 Mueller C. Gottlieb Burckhardt, the father of topectomy. Am J Psychiatry. 1960;117:461-463.

14 Puusepp L. Alcune considerazioni sugli interventi chirurgici nelle malattie mentali. G Acad Med Torino. 1937;100:3-16.

15 Brickner R. An interpretation of function based upon a case of bilateral frontal lobectomy. Proc Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1932;13:259-351.

16 Penfield W, Evans J. The frontal lobe in man: a clinical study of maximal removals. Brain. 1935;58:115-133.

17 Bailey P. Intracranial Tumors. Sprinfield, Ill: Charles C Thomas; 1948.

18 Horowitz N. John F. Fulton (1899-1960). Neurosurgery. 1998;43:178-184.

19 Kopell BH, Rezai AR. Psychiatric neurosurgery: a historical perspective. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:181-197.

20 Moniz E. Prefrontal leucotomy in the treatment of mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1935;93:1379-1385.

21 Moniz E. Essai d’un traitement chirurgical de certaine psychoses. Bull Acad Med. 1936;115:385-392.

22 Deutsch A. The Mentally Ill in America. New York: Doubleday; 1937.

23 Mashour GA, Walker EE, Martuza RL. Psychosurgery: past, present, and future. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2005;48:409-419.

24 Freeman W. Frontal lobotomy in early schizophrenia. Long follow-up in 415 cases. Br J Psychiatry. 1971;119:621-624.

25 Freeman W. Transorbital leucotomy. Lancet. 1948;2:371-373.

26 Feldman RP, Goodrich JT. Psychosurgery: a historical overview. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:647-657.

27 Fins JJ. From psychosurgery to neuromodulation and palliation: history’s lessons for the ethical conduct and regulation of neuropsychiatric research. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:303-319.

28 Rylander G. Therapeutic results of different types of frontal lobe operation. Acta Psychiatr Neurol Scand Suppl. 1952;80:122-128.

29 Scoville WB. Selective cortical undercutting as a means of modifying and studying frontal lobe function in man: preliminary report of forty-three operative cases. J Neurosurg. 1949;6:65-73.

30 Scoville WB. Selective cortical undercutting; a new method of fractional lobotomy. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1951;56:224-226.

31 Scoville WB. Orbital undercutting in the treatment of psychoneuroses, depressions and senile emotional states; psychiatric and physiologic results of fractional lobotomy in the milder emotional illnesses. Dis Nerv Syst. 1954;15:324-334.

32 Scoville WB. Orbital undercutting in the treatment of psychoneuroses, depressions and senile emotional states; results of fractional lobotomy in the benign psychiatric disorders. Med Contemp. 1955;73:151-154.

33 Scoville WB. Late results of orbital undercutting. Report of 76 patients undergoing quantitative selective lobotomies. Am J Psychiatry. 1960;117:525-532.

34 Strom-Olsen R, Northfield DW. Undercutting of orbital cortex in chronic neurotic and psychotic tension states. Lancet. 1955;268:986-991.

35 Knight GC, Tredgold RF. Orbital leucotomy; a review of 52 cases. Lancet. 1955;268:981-986.

36 Pool JL, Ransohoff J. Autonomic effects on stimulating rostral portion of cingulate gyri in man. J Neurophysiol. 1949;12:385-392.

37 Saubidet R, Lyonnet J, Brichetti D. Undercutting of lateral aspects of frontal lobes for treatment in the chronic paranoid psychosis, paraphrenia. In: Sweet WH, Obrador S, Martín-Rodríguez JG, editors. Neurosurgical Treatment in Psychiatry, Pain, and Epilepsy. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1975:225-228.

38 Bailey HR, Dowling JL, Davies E. Cingulotractotomy and related procedures for severe depressive illness (studies in depression: IV). In: Sweet WH, Obrador S, Martín-Rodríguez JG, editors. Neurosurgical Treatment in Psychiatry, Pain, and Epilepsy. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1975:229-251.

39 Vilkii J. Late psychological and clinical effects of subrostral cingulotomy and anterior mesoloviotomy in psychiatric illness. In: Sweet WH, Obrador S, Martín-Rodríguez JG, editors. Neurosurgical Treatment in Psychiatry, Pain, and Epilepsy. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1975:253-259.

40 Hunter Brown M, Lighthill JA. Selective anterior cingulotomy: a psychosurgical evaluation. J Neurosurg. 1968;29:513-519.

41 Spiegel EA, Wycis HT, Marks M, Lee AJ. Stereotaxic apparatus for operations on the human brain. Science. 1947;106:349-350.

42 Knight G. The orbital cortex as an objective in the surgical treatment of mental illness. The results of 450 cases of open operation and the development of the stereotactic approach. Br J Surg. 1964;51:114-124.

43 Knight G. Further observations from an experience of 660 cases of stereotactic tractotomy. Postgrad Med J. 1973;49:845-854.

44 Knight GC. Bi-frontal stereotactic tractotomy: an atraumatic operation of value in the treatment of intractable psychoneurosis. Br J Psychiatry. 1969;115:257-266.

45 Malhi GS, Bartlett JR. A new lesion for the psychosurgical operation of stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy (SST). Br J Neurosurg. 1998;12:335-339.

46 Bridges PK, Bartlett JR, Hale AS, et al. Psychosurgery: stereotactic subcaudate tractomy. An indispensable treatment. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;165:599-611.

47 Hodgkiss AD, Malizia AL, Bartlett JR, Bridges PK. Outcome after the psychosurgical operation of stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy, 1979-1991. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1995;7:230-234.

48 Jenike MA. Neurosurgical treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 1998:79-90.

49 Lovett LM, Crimmins R, Shaw DM. Outcome in unipolar affective disorder after stereotactic tractotomy. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;155:547-550.

50 Lovett LM, Shaw DM. Outcome in bipolar affective disorder after stereotactic tractotomy. Br J Psychiatry. 1987;151:113-116.

51 Poynton A, Bridges PK, Bartlett JR. Resistant bipolar affective disorder treated by stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy. Br J Psychiatry. 1988;152:354-358.

52 Poynton AM, Kartsounis LD, Bridges PK. A prospective clinical study of stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy. Psychol Med. 1995;25:763-770.

53 Ramamurthi B. Thermocoagulation for stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy. Br J Neurosurg. 1999;13:219.

54 Kartsounis LD, Poynton A, Bridges PK, Bartlett JR. Neuropsychological correlates of stereotactic subcaudate tractotomy. A prospective study. Brain. 1991;114(Pt 6):2657-2673.

55 Papez JW. Proposed mechanisms of emotion. Arch Neurol Psychiatry. 1937;38:725-743.

56 Le Beau J. Anterior cingulectomy in man. J Neurosurg. 1954;11:268-276.

57 Livingston KE. The frontal lobes revisited. The case for a second look. Arch Neurol. 1969;20:90-95.

58 Tow PM, Armstrong RW, Oxon MA. Anterior cingulectomy in schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders; clinical results. J Ment Sci. 1954;100:46-61.

59 Whitty CW, Duffield JE, Tov PM, Cairns H. Anterior cingulectomy in the treatment of mental disease. Lancet. 1952;1:475-481.

60 Baer L, Rauch SL, Ballantine HTJr, et al. Cingulotomy for intractable obsessive-compulsive disorder. Prospective long-term follow-up of 18 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52:384-392.

61 Ballantine HTJr, Bouckoms AJ, Thomas EK, Giriunas IE. Treatment of psychiatric illness by stereotactic cingulotomy. Biol Psychiatry. 1987;22:807-819.

62 Ballantine HTJr, Cassidy WL, Flanagan NB, Marino RJr. Stereotaxic anterior cingulotomy for neuropsychiatric illness and intractable pain. J Neurosurg. 1967;26:488-495.

63 Ballantine HTJ, Levy BS, Dagi TF, Giriunas IB. Cingulotomy for psychiatric illness: report of 13 years’ experience. In: Sweet WH, Obrador S, Martín-Rodríguez JG, editors. Neurosurgical Treatment in Psychiatry, Pain, and Epilepsy. Baltimore: University Park Press; 1975:333-353.

64 Jenike MA, Baer L, Ballantine T, et al. Cingulotomy for refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. A long-term follow-up of 33 patients. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:548-555.

65 Martuza RL, Chiocca EA, Jenike MA, et al. Stereotactic radiofrequency thermal cingulotomy for obsessive compulsive disorder. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1990;2:331-336.

66 Shields DC, Asaad W, Eskandar EN, et al. Prospective assessment of stereotactic ablative surgery for intractable major depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:449-454.

67 Richter EO, Davis KD, Hamani C, et al. Cingulotomy for psychiatric disease: microelectrode guidance, a callosal reference system for documenting lesion location, and clinical results. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:622-628.

68 Steele JD, Christmas D, Eljamel MS, Matthews K. Anterior cingulotomy for major depression: clinical outcome and relationship to lesion characteristics. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:670-677.

69 Dougherty DD, Baer L, Cosgrove GR, et al. Prospective long-term follow-up of 44 patients who received cingulotomy for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:269-275.

70 Bridges PK, Bartlett JR. Limbic leucotomy. Br J Psychiatry. 1976;129:399-400.

71 Kelly D. Psychosurgery and the limbic system. Postgrad Med J. 1973;49:825-833.

72 Kelly D. Therapeutic outcome in limbic leucotomy in psychiatric patients. Psychiatr Neurol Neurochir. 1973;76:353-363.

73 Kelly D, Mitchell-Heggs N. Stereotactic limbic leucotomy—a follow-up study of thirty patients. Postgrad Med J. 1973;49:865-882.

74 Kelly D, Richardson A, Mitchell-Heggs N, et al. Stereotactic limbic leucotomy: a preliminary report on forty patients. Br J Psychiatry. 1973;123:141-148.

75 Mitchell-Heggs N, Kelly D, Richardson A. Stereotactic limbic leucotomy—a follow-up at 16 months. Br J Psychiatry. 1976;128:226-240.

76 Montoya A, Weiss AP, Price BH, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging-guided stereotactic limbic leukotomy for treatment of intractable psychiatric disease. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:1043-1049.

77 Price BH, Baral I, Cosgrove GR, et al. Improvement in severe self-mutilation following limbic leucotomy: a series of 5 consecutive cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:925-932.

78 Richardson A. Stereotactic limbic leucotomy: surgical technique. Postgrad Med J. 1973;49:860-864.

79 Fodstad H, Strandman E, Karlsson B, West KA. Treatment of chronic obsessive compulsive states with stereotactic anterior capsulotomy or cingulotomy. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1982;62:1-23.

80 Mindus P, Edman G, Andreewitch S. A prospective, long-term study of personality traits in patients with intractable obsessional illness treated by capsulotomy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;99:40-50.

81 Mindus P, Nyman H. Normalization of personality characteristics in patients with incapacitating anxiety disorders after capsulotomy. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1991;83:283-291.

82 Ruck C, Andreewitch S, Flyckt K, et al. Capsulotomy for refractory anxiety disorders: long-term follow-up of 26 patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:513-521.

83 Deep-brain stimulation of the subthalamic nucleus or the pars interna of the globus pallidus in Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:956-963.

84 Deuschl G, Schade-Brittinger C, Krack P, et al. A randomized trial of deep-brain stimulation for Parkinson’s disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:896-908.

85 Kupsch A, Benecke R, Muller J, et al. Pallidal deep-brain stimulation in primary generalized or segmental dystonia. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1978-1990.

86 Levy RM. Deep brain stimulation for the treatment of intractable pain. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2003;14:389-399.

87 Levy RM, Lamb S, Adams JE. Treatment of chronic pain by deep brain stimulation: long term follow-up and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:885-893.

88 Schuurman PR, Bosch DA, Bossuyt PM, et al. A comparison of continuous thalamic stimulation and thalamotomy for suppression of severe tremor. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:461-468.

89 Vidailhet M, Vercueil L, Houeto JL, et al. Bilateral deep-brain stimulation of the globus pallidus in primary generalized dystonia. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:459-467.

90 Wallace BA, Ashkan K, Benabid AL. Deep brain stimulation for the treatment of chronic, intractable pain. Neurosurg Clin N Am. 2004;15:343-357.

91 Schiff ND, Giacino JT, Kalmar K, et al. Behavioural improvements with thalamic stimulation after severe traumatic brain injury. Nature. 2007;448:600-603.

92 Franzini A, Marras C, Ferroli P, et al. Stimulation of the posterior hypothalamus for medically intractable impulsive and violent behavior. Stereotact Funct Neurosurg. 2005;83:63-66.

93 Franzini A, Ferroli P, Leone M, Broggi G. Stimulation of the posterior hypothalamus for treatment of chronic intractable cluster headaches: first reported series. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1095-1099.

94 Leone M, Franzini A, Broggi G, et al. Long-term follow-up of bilateral hypothalamic stimulation for intractable cluster headache. Brain. 2004;127:2259-2264.

95 Hamani C, McAndrews MP, Cohn M, et al. Memory enhancement induced by hypothalamic/fornix deep brain stimulation. Ann Neurol. 2008;63:119-123.

96 Anderson D, Ahmed A. Treatment of patients with intractable obsessive-compulsive disorder with anterior capsular stimulation. Case report. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:1104-1108.

97 Aouizerate B, Martin-Guehl C, Cuny E, et al. Deep brain stimulation for OCD and major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:2192.

98 Greenberg BD, Malone DA, Friehs GM, et al. Three-year outcomes in deep brain stimulation for highly resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2384-2393.

99 Lipsman N, Neimat JS, Lozano AM. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-refractory obsessive-compulsive disorder: the search for a valid target. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:1-11.

100 Nuttin B, Cosyns P, Demeulemeester H, et al. Electrical stimulation in anterior limbs of internal capsules in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Lancet. 1999;354:1526.

101 Nuttin BJ, Gabriels LA, Cosyns PR, et al. Long-term electrical capsular stimulation in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1263-1272.

102 Agid Y, Buzsaki G, Diamond DM, et al. How can drug discovery for psychiatric disorders be improved? Nat Rev. 2007;6:189-201.

103 Lozano AM, Mayberg HS, Giacobbe P, et al. Subcallosal cingulate gyrus deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:461-467.

104 Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Voon V, et al. Deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression. Neuron. 2005;45:651-660.

105 Mayberg HS. Limbic-cortical dysregulation: a proposed model of depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9:471-481.

106 Mayberg HS. Positron emission tomography imaging in depression: a neural systems perspective. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2003;13:805-815.

107 Mayberg HS, Liotti M, Brannan SK, et al. Reciprocal limbic-cortical function and negative mood: converging PET findings in depression and normal sadness. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:675-682.

108 Giacobbe P, Hamani C, Kennedy SH, et al. Deep brain stimulation for major depressive disorder (resistant to 4 or more treatments): Preliminary results of a multi-centre study. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:205S.

109 McNeely HE, Mayberg HS, Lozano AM, Kennedy SH. Neuropsychological impact of Cg25 deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: preliminary results over 12 months. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:405-410.

110 Neimat JS, Hamani C, Giacobbe P, et al. Neural stimulation successfully treats depression in patients with prior ablative cingulotomy. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:687-693.

111 Jimenez F, Velasco F, Salin-Pascual R, et al. A patient with a resistant major depression disorder treated with deep brain stimulation in the inferior thalamic peduncle. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:585-593.

112 Jimenez F, Velasco F, Salin-Pascual R, et al. Neuromodulation of the inferior thalamic peduncle for major depression and obsessive compulsive disorder. Acta Neurochir Suppl. 2007;97:393-398.

113 Velasco F, Velasco M, Jimenez F, et al. Neurobiological background for performing surgical intervention in the inferior thalamic peduncle for treatment of major depression disorders. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:439-448.

114 Schlaepfer TE, Cohen MX, Frick C, et al. Deep brain stimulation to reward circuitry alleviates anhedonia in refractory major depression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:368-377.

115 Malone DAJr, Dougherty DD, Rezai AR, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the ventral capsule/ventral striatum for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:267-275.

116 Rush AJ, George MS, Sackeim HA, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant depressions: a multicenter study. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:276-286.

117 Ben-Menachem E, Hamberger A, Hedner T, et al. Effects of vagus nerve stimulation on amino acids and other metabolites in the CSF of patients with partial seizures. Epilepsy Res. 1995;20:221-227.

118 Carpenter LL, Moreno FA, Kling MA, et al. Effect of vagus nerve stimulation on cerebrospinal fluid monoamine metabolites, norepinephrine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid concentrations in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:418-426.

119 Hammond EJ, Uthman BM, Wilder BJ, et al. Neurochemical effects of vagus nerve stimulation in humans. Brain Res. 1992;583:300-303.

120 Chae JH, Nahas Z, Lomarev M, et al. A review of functional neuroimaging studies of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS). J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:443-455.

121 Henry TR, Bakay RA, Votaw JR, et al. Brain blood flow alterations induced by therapeutic vagus nerve stimulation in partial epilepsy: I. Acute effects at high and low levels of stimulation. Epilepsia. 1998;39:983-990.

122 Elger G, Hoppe C, Falkai P, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation is associated with mood improvements in epilepsy patients. Epilepsy Res. 2000;42:203-210.

123 Harden CL, Pulver MC, Ravdin LD, et al. A pilot study of mood in epilepsy patients treated with vagus nerve stimulation. Epilepsy Behav. 2000;1:93-99.

124 Nahas Z, Marangell LB, Husain MM, et al. Two-year outcome of vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment of major depressive episodes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:1097-1104.

125 Rush AJ, Marangell LB, Sackeim HA, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation for treatment-resistant depression: a randomized, controlled acute phase trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:347-354.

126 Rush AJ, Sackeim HA, Marangell LB, et al. Effects of 12 months of vagus nerve stimulation in treatment-resistant depression: a naturalistic study. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:355-363.

127 Sackeim HA, Rush AJ, George MS, et al. Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) for treatment-resistant depression: efficacy, side effects, and predictors of outcome. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:713-728.

128 Marangell LB, Martinez M, Jurdi RA, Zboyan H. Neurostimulation therapies in depression: a review of new modalities. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2007;116:174-181.

129 Sackeim HA, Keilp JG, Rush AJ, et al. The effects of vagus nerve stimulation on cognitive performance in patients with treatment-resistant depression. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol. 2001;14:53-62.

130 George MS, Rush AJ, Marangell LB, et al. A one-year comparison of vagus nerve stimulation with treatment as usual for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:364-373.

131 Corcoran CD, Thomas P, Phillips J, O’Keane V. Vagus nerve stimulation in chronic treatment-resistant depression: preliminary findings of an open-label study. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189:282-283.