Chapter 28 Surgical Sterilization

HISTORY

In the 1970s tubal sterilization became widespread due to the introduction of minilaparotomy and laparoscopy as methods. Anderson1 is credited with performing the first laparoscopic electrocoagulation procedure in the United States in 1937. Steptoe2 in 1967 reported the first large series of laparoscopic sterilizations, and Wheeless3 in 1973 reported the first single-puncture laparoscopic technique. These procedures allowed for interval surgery, surgery without hospital stay, reduced recovery time, less morbidity, and better cosmetic result.4 Sterilization is now the most commonly used method of family planning in the world.

PREOPERATIVE EVALUATION

Tubal sterilization should be available to any woman who desires permanent sterilization, assuming that she has proper informed consent (Table 28-1) and adequate knowledge regarding the procedure. The procedure should be considered purely elective. There are virtually no absolute contraindications to tubal sterilization except for gynecologic malignancy or gynecologic disease that requires hysterectomy or bilateral oophorectomy.

| Review of alternative methods of permanent sterilization (e.g., vasectomy) |

| Indication that the procedure is considered permanent |

| Review of failure rate of procedure |

| Description of the planned operative technique |

| Discussion of potential surgical risks |

Informed Consent

Various materials are available to assist the physician in counseling the patient. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) distributes a pamphlet that discusses different techniques of sterilization as well as alternative methods for contraception. For couples desiring permanent sterilization, vasectomy should always be discussed because vasectomy is associated with fewer complications than tubal sterilization. When counseling the patient on the benefits of sterilization, it is important to include that all methods are extremely effective, are permanent, and have a low failure rate.5 Risks of the female sterilization procedure include risk of anesthesia, operative surgical risks, and the 1% to 3% risk of failure with an increased risk of ectopic pregnancy. It should be remembered that patients whose sterilization will be federally funded must sign a special consent document and must be at least 21 years old.

Sterilization Regret

Anywhere from 3% to 25% of women have regret about sterilization, and 1% to 2% of these patients actually seek tubal reversal. Some reasons for regret (Table 28-2) include change in marital status, death of a child, and wanting another child after other children have gotten older. Studies have shown that there is an increased risk of regret with change in marital status, age less than 30 at the time of sterilization, psychiatric history, postpartum sterilization, poor outcome with previous delivery, and ongoing marital, financial, health, or personal problems at the time of sterilization.5

Table 28-2 Factors That Have and Have Not Been Associated with Regret After Sterilization

| Factors Associated with Regret | Factors Not Associated with Regret |

|---|---|

| Marital status change | Religion |

| Family stress (e.g., death of a child) | Socioeconomic level |

| Desire for additional children as the “baby” grows up | Education level |

| Post-tubal ligation syndrome symptoms | Low parity |

| Postpartum procedure | Decision made with husband’s approval |

| Sterilization before age 30 | Interval procedure |

TIMING

Postpartum Sterilization

Sterilization after delivery, during the patient’s postpartum hospital stay, is a convenient, effective, and efficient way to prevent future pregnancy. In the immediate postpartum period the uterus is enlarged to the level of the umbilicus, making it convenient to perform sterilization with a small 1- to 2-cm infraumbilical incision. Any of several techniques could be used. The longest period that the patient may wait before undergoing sterilization is controversial. In some circumstances, a delay of 12 to 24 hours may be needed to assess the infant’s condition, or delays secondary to staffing patterns or availability of anesthesia may be encountered. Studies done show no increased risk of morbidity if the sterilization is delayed for the first postpartum day.6,7 If it is not feasible during this time period to perform the sterilization, the patient should probably wait at least 6 weeks so that the uterine architecture will be back to normal. Before this time, the uterus may be enlarged, making laparoscopy more difficult, and there may be an increased risk of infection during the postpartum period. The patient who has a postpartum endometritis or has had premature rupture of the membranes, intrapartum fever, or manual placental removal is probably at risk of a postsurgical infection. Therefore, it may be prudent for this patient to wait and undergo interval sterilization.

Interval Sterilization

Interval sterilization after the immediate postpartum period should be delayed for 6 or 8 weeks. Most of these procedures are performed by laparoscopy and can be done using local, conduction, or general anesthesia. Performance of the procedure during the menstrual or proliferative phase of the cycle reduces the chance of pregnancy at the time of the procedure. However, if this is not practical, a sensitive urine or serum pregnancy test can be done on the day the procedure is performed. This too has been shown to decrease the risk of luteal phase pregnancy.8 Finally, sterilization can be performed in conjunction with other surgical procedures, such as cholecystectomy or plastic surgical procedures.

STERILIZATION METHODS

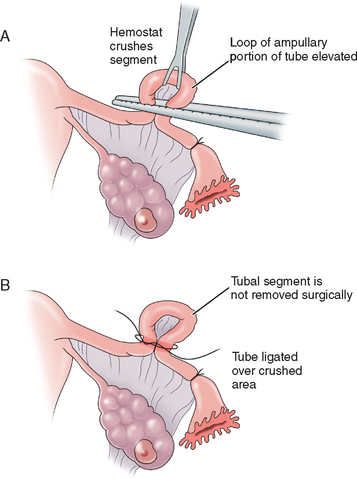

Madlener Technique

The Madlener technique involves forming a loop of tube, of which a portion is crushed at the base of the loop and ligated with a nonabsorbable suture. Occlusion but not division of the lumen is achieved (Fig. 28-1). The end result is similar to the laparoscopic placement of a Silastic band for occlusion, as described in the section on the Falope ring in this chapter. Failures are often attributed to fistula formation at the ligature site. This technique is generally of historic interest only.

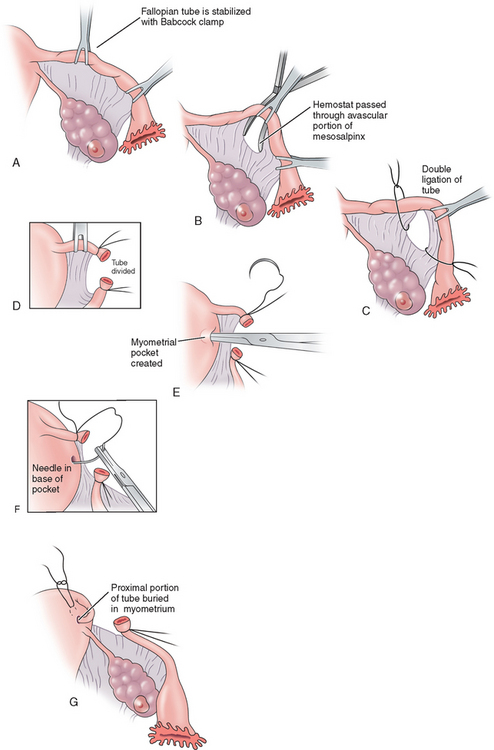

Irving Procedure

The Irving procedure was introduced as a technique for ligation and division of the oviduct at the time of cesarean section. At the ampullary–isthmic junction, the proximal stump is buried within the myometrium and the distal stump is buried between the leaves of the broad ligament (Fig. 28-2). As the uterus undergoes involution postpartum, the buried proximal and distal ends of the tubes become compressed and eventually obliterated. This procedure takes longer and there is often more blood loss; however, the chances of tubal recanalization or pregnancy in the proximal stump are remote.

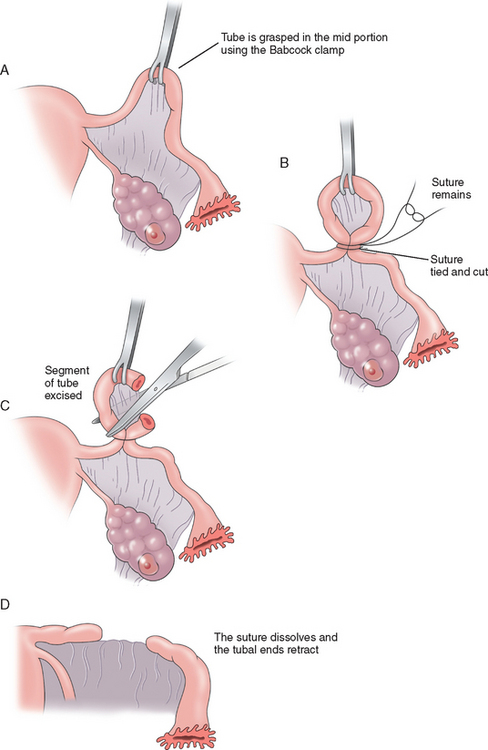

Pomeroy Method

The Pomeroy method (Fig. 28-3) or its modifications are probably the most commonly used sterilization procedures today. A knuckle of tube is grasped at the midportion using a Babcock clamp. This segment of tube, approximately 2cm in length, is then ligated at the base with an absorbable suture, preferably plain gut. This segment of tube is then excised and sent to the pathology laboratory for confirmation. The use of absorbable sutures allows the proximal and distal segments of the tube to separate, thus decreasing the risk of recanalization of the tube. The advantages to the Pomeroy method are that it is easy and quick to perform and highly effective. Its acceptance for both postpartum and interval sterilization is quite high.

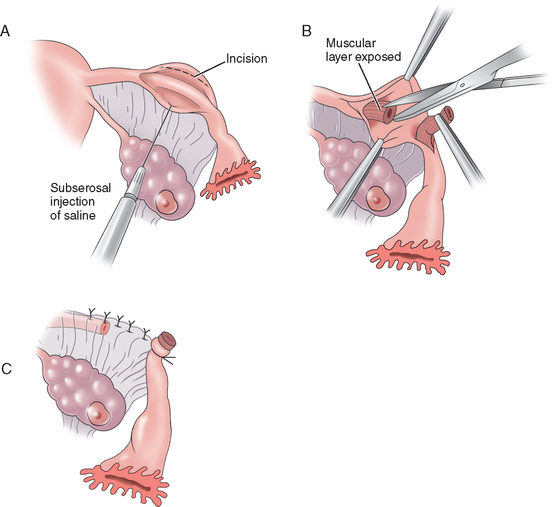

Uchida Technique

The Uchida technique is one of the more complex methods of tubal sterilization. It involves injection of a saline–epinephrine solution to the subserosal aspect of the tube, separating the muscular portion of the tube from the serosa. The serosa is then dissected off the muscular tube and a 5-cm segment of tube is excised while the proximal end is ligated and allowed to retract into the mesosalpinx. The mesosalpinx is then closed and a pursestring stitch is placed around the distal end to secure its position open to the abdomen (Fig. 28-4). A fimbriectomy may be added to this procedure to enhance effectiveness and prevent reanastomosis. The Uchida technique is more complicated than the other procedures but has been associated with very few failures.

Fimbriectomy

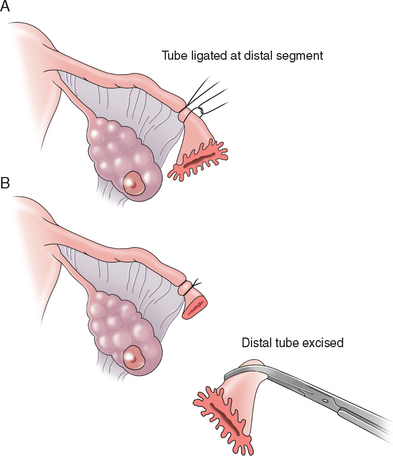

The technique of fimbriectomy described by Kroener employs the ligation of the distal ampulla with two permanent sutures and division and removal of the tubal infundibulum (Fig. 28-5). The simplicity of this procedure accounted for its popularity, but fimbriectomy does not seem to have many advocates due to the availability of easier and much more effective procedures.

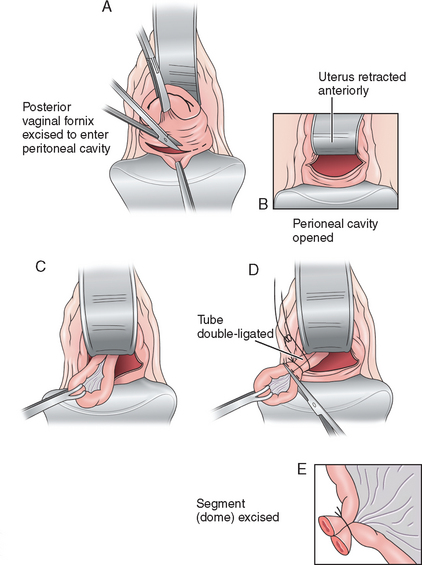

Vaginal Approach

Theoretically the vaginal approach (Fig. 28-6) seems ideal for safe and rapid tubal sterilization and has the advantage of avoiding an abdominal incision. However, the potential complications and complexity of the procedure prevent its widespread popularity. The possible complications from this procedure are cellulitis, hemorrhage, infection, cuff abscess, and bowel and bladder damage. Deep dyspareunia may also be a complication with some patients.

The patient is placed in the dorsal lithotomy or knee-chest position. A right-angle or Dever retractor is used to expose the cervix, which is grasped on its posterior lip with a single-toothed tenaculum. The posterior cul-de-sac is exposed, and a colpotomy incision is performed using Mayo scissors. The tips of the scissors are placed in the peritoneal opening and spread to enlarge the incision. The anterior retractor is placed posterior to the cervix just inside the incision and is elevated. This maneuver results in retroflexion of the uterus. The fallopian tube is grasped with a Babcock clamp and brought into the operative field. The sterilization can be accomplished using tubal bands, electrocautery, or clips.9 However, the most common method described is the use of the Pomeroy technique.10 Once completed, the colpotomy incision is closed using interrupted figure-of-eight sutures or a single running suture of an absorbable suture material.

Laparoscopic Sterilization

Unipolar Coagulation

Unipolar coagulation was the first method of laparoscopic tubal occlusion to achieve widespread use. The overall concept of the unipolar method involves the use of a grounded, high-voltage generator that produces a coagulating current. Electrical energy is concentrated at a site grasped by operating forceps, with some lateral spread, and from this site, current travels through the patient’s body and exits at the return electrode (the grounding pad) on the patient’s skin. The laparoscopic unipolar procedure involves operative forceps, which are advanced through the operative site where the isthmic–ampullary portion of the tube is grasped and a 2- to 3-cm segment of tube is burned. Some surgeons combine electrocoagulation with transection or resection of a small part of the coagulated tube; however, the failure rate is not improved and the risk of damage to the mesosalpinx and subsequent hemorrhage is increased. Although the unipolar method is still used, its popularity has declined due to the increased risk of thermal injury to the bowel from capacitance.

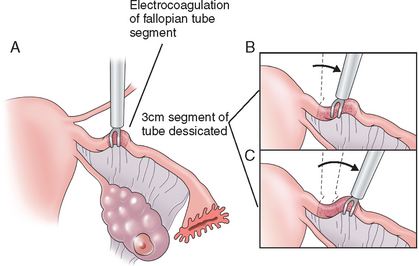

Bipolar Coagulation

The bipolar form of electrocautery was next introduced. This differs from the unipolar method in that the operating forceps carries both the active and the return electrode. With this method, a cutting current is used at 25 watts of power, because the coagulation current used with the unipolar method does not cause deep enough tissue damage to the tube and can lead to an intact lumen and increased failure rate. The isthmic portion of the tube is grasped and a 3-cm segment of tube is desiccated (Fig. 28-7). An ammeter is used to confirm proper coagulation through full-tissue thickness. This method prevents the spread of current to other organs and decreases the risk of bowel injury. This is the most common laparoscopic method for tubal ligation because it is technically the easiest, does not require mobile tubes, and is applicable with edematous tubes.

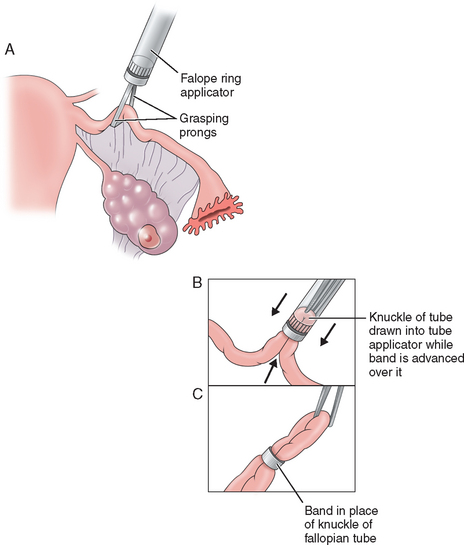

Falope Ring

The Falope ring, devised by Yoon, was the first nonthermal laparoscopic method for tubal occlusion. It involves drawing a 2-cm loop of tube 2 to 3cm distal to the uterotubal junction into one of the two concentric cylinders of the ring applicator; then a Silastic band is passed over this loop, causing occlusion of the tube (Fig. 28-8). Because the Falope ring works by necrosis of the tissue in the band, local anesthesia is often applied to the tube to prevent postoperative pain.11 Although the failure rate of this procedure is low, this procedure is limited to nonedematous, mobile tubes. Occasionally, tubal transection and damage to the mesosalpinx can occur, which is why experienced clinicians should perform this procedure.

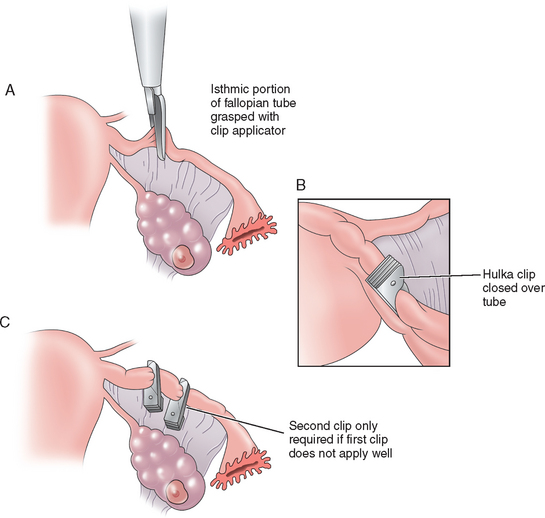

Clips

Hulka first reported the use of a spring clip for tubal sterilization in 1973. The Hulka clip, made of Lexan plastic, is maintained in its closed position by a gold-plated spring that diminishes peritoneal reaction. The interlocking plastic teeth compress the tube and obliterate the lumen of the tube. Placement is crucial with this clip. The clip is applied to the isthmic portion of the tube about 2cm from the uterus and exactly at right angles to the tube. The jaws should be pressed against the tube with the tip of the clip extending onto the mesosalpinx, forming the characteristic envelope sign (Fig. 28-9). Like the Falope ring, this method works by necrosis; therefore, local anesthetic on the tube is preferable. This clip is most successful when placed on a normal tube because thickening of the tube, distortion, and adhesions may make application difficult and increase failure rates. One advantage to this method is that only a small portion of tube is damaged, which makes reanastomosis procedures more successful.

A few years after the development of the Hulka clip, Filshie developed a clip with jaws of titanium and an inner cushion of silicone rubber. When the jaws close, the silicone rubber expands as tube necrosis occurs, causing complete occlusion of the tube and lumen. The Filshie clip is the easiest to apply due to the grasping effect from the curve on the upper jaw. This clip, like the Hulka, is placed at a right angle on the isthmic portion of the tube 2 to 2.5cm distal to the uterotubal junction, after application of local anesthetic on the portion of the tube to be obliterated. Because of its length, the Filshie clip can be placed on any type and shape of tube, including postpartum.12,13 Several randomized clinical trials compared the Hulka clip to the Filshie clip and showed that the failure rate with the Hulka is slightly higher (1.0 per 1000 for Filshie vs. 7.0 per 1000 for Hulka). This method also only destroys a small segment of tube, making tubal reversals easier.

Tubal Ligation Under Local Anesthesia

Advantages of this are that it avoids the risks associated with general anesthesia and decreases the cost of anesthesia. This is due to the fact that anesthesia time is decreased and recovery time is shortened with less postoperative nausea and vomiting with local anesthesia compared to general anesthesia.

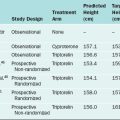

Regimens

Local anesthesia regimens usually consist of three types of drugs: systemic agents that sedate the patient and block pain (midazolam, fentanyl, sufentanil, alfentanil), local analgesics that relieve pain at the incision site (bupivicaine),4 and systemic drugs that prevent nausea or disturbance of heart function (promethazine, atropine).

Results of tubal ligation under local anesthesia are similar to those found under general anesthesia, with similar patient satisfaction, but less operating time. In a study by Mackenzie and colleagues that looked at postoperative effects of local anesthesia, they found that 21% of patients left the clinic within 4 hours of the operation and all patients had left after 7 hours. Ninety eight percent of patients were satisfied with the procedure under local anesthesia, and 94% would actually recommend the procedure to a friend.14

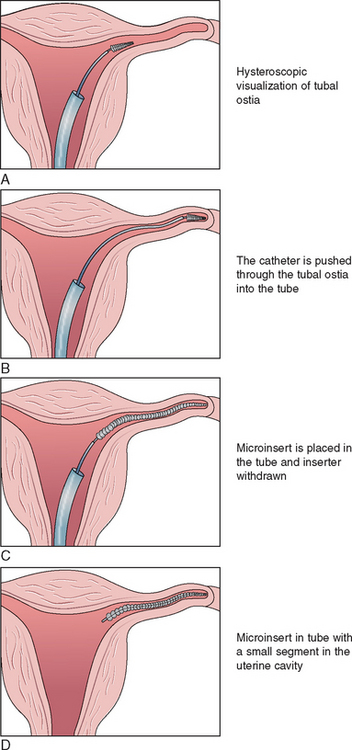

Hysteroscopic Sterilization

Plugs

Three plugtype devices have reached human clinical trials, and the Essure device has been approved by the U.S. FDA (Fig. 28-10). The Essure procedure is a nonincisional surgical procedure that involves placing a small, flexible device called a micro-insert into each of the fallopian tubes. The micro-inserts are made from polyester fibers and metals (nickel–titanium and stainless steel).15 Once the micro-inserts are in place, tissue ingrowth occurs into the micro-inserts, blocking the fallopian tubes. Nickel allergy, recent pelvic infection, and possibly hydrosalpinx are contraindications to the procedure. A hysterosalpingogram must be done 3 months after the procedure to ensure and document tubal occlusion.

Two separate studies of the safety and effectiveness of the Essure method have been conducted in women from the United States, Australia, and Europe. In the first study, 192 women relied on Essure for contraception for 1 year, 177 relied on Essure for contraception for 2 years, and 172 relied on Essure for contraception for 3 years. In the second study, 434 women relied on Essure for contraception for 1 year, 403 relied on Essure for contraception for 2 years and 21 for 3 years. None of the women who relied on Essure for contraception during the clinical trials became pregnant over the 1 to 3 years of follow-up.16

COMPLICATIONS

Surgical Complications

Tubal ligation carries the small risk associated with the surgical approach used, be it minilaparotomy or laparoscopy. In general, the major complication rate, defined as requiring a laparotomy, is less than 1%. Complications include anesthesia reactions, pelvic infections, and injury to intra-abdominal structures, including blood vessels, bowel, and bladder. Laparoscopic complications are described in more depth in Chapter 45.

Sterilization Failure

U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization (CREST) Study

This study was a multicenter, prospective study involving 10,685 women who had been sterilized who were then followed for 8 to 14 years to determine their probability of pregnancy.17–19 The techniques studied were silicone rubber rings, bipolar electrocoagulation, postpartum partial salpingectomy, spring clip application, unipolar coagulation, and interval partial salpingectomy. Among these women, 143 sterilization failures occurred, with 32.9% being ectopic pregnancies. The cumulative 10-year probability of pregnancy was lowest after unipolar coagulation and postpartum partial salpingectomy, and highest with spring clip application. Results with the Filshie clip were not reported.

Delayed Complications

Post-sterilization Syndrome

Although tubal sterilization is a very effective method of contraception, some delayed complications may occur. Significant abnormal bleeding can occur after sterilization, leading to menstrual changes. This condition has been called post-sterilization syndrome (pain, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, and premenstrual tension). In the United States 30% of women receiving tubal sterilization were taking oral contraceptive pills immediately before their procedure, and their menstrual changes may be attributed solely to oral contraception cessation. Multiple studies have been performed to look at the connection between sterilization and menstrual changes and have concluded that menstrual changes in the first 2 years after sterilization are not attributed to sterilization, thus negating the post-sterilization syndrome theory.20 Whether menstrual changes that occur long after sterilization are attributable to the procedure is less clear.

SUMMARY

1 Anderson ET. Peritoneoscopy. Am J Surg. 1937;35:136-138.

2 Steptoe PC. Laparoscopy in Gynaecology. Edinburgh: E. and S. Livingston Ltd., 1967.

3 Wheeless CRJr. Elimination of second incision in laparoscopic sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 1972;39:134-136.

4 Soderstrom: Food and Drug Administration advisory panel on sterilization: Randomized, controlled trials of Filshie clip (1996).

5 Penney GC, Souter V, Glasier A, Templeton AA. Laparoscopic sterilization: Opinion and practice among gynacologists in Scotland. BJOG. 1997;104:71-77.

6 Black WP, Sclare AB. Sterilization by tubal ligation—a follow-up study. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1968;75:219-224.

7 Green LR, Laros RK. Postpartum sterilization. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1980;23:647-659.

8 Lipscomb GH, Spellman JR, Ling FW. The effect of same-day pregnancy testing on the incidence of luteal phase pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:411-413.

9 Hartfield VJ. Female sterilization by the vaginal route: A positive reassessment and comparison of four tubal occlusion methods. Austral NZ J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;33:408-412.

10 Hartfield VJ. Day care Pomeroy sterilization by the vaginal route. NZ Med J. 1977;85:223-225.

11 Ezeh UO, Shoulder V, Martin JL, et al. Local anesthetic on Filshie clips for pain relief after tubal sterilization: A randomized double-blinded control trial. Lancet. 1995;34:82-85.

12 Filshie GM, Casey D, Pogmore JR, et al. The titanium/silicone rubber clip for female sterilization. BJOG. 1981;88:655-662.

13 Graf AH, Staudach A, Steiner H, et al. An evaluation of the Filshie clip for postpartum sterilization in Austria. Contraception. 1996;54:309-311.

14 MacKenzie IZ, Turner E, O’Sullivan GM, Guillebaud J. Two hundred out-patient laparoscopic clip sterilizations using local anesthesia. BJOG. 1987;94:449-453.

15 Valle RF, Carignan CS, Wright TC, the STOP Preshysterectomy Investigation Group. Tissue response to the STOP microcoil transcervical permanent contraceptive device: Results from a prehysterectomy study. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:974-980.

16 Cooper JM, Canignan CS, Chen D, et al. Microinsert nonincisional hysteroscopic sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:59-61.

17 Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Tylor LR, Peterson HB, for the U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization Working Group. Higher hysterectomy risk for sterilized than nonsterilized women: Findings from the U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:241-246.

18 Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Tylor LR, Peterson HB, for the U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization Working Group. Poststerilization regret: Findings from the U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;93:889-895.

19 Hillis SD, Marchbanks PA, Tylor LR, Peterson HB, for the U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization Working Group. Tubal sterilization and long-term risk of hysterectomy: Findings from the U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:609-614.

20 Peterson HB, Jeng G, Folger SG, Hillis SA, et alfor the U.S. Collaborative Review of Sterilization Working Group. The risk of menstrual abnormalities after tubal sterilization. NEJM. 2000;343:1681-1687.