Chapter 30 Pelvic Ultrasonography and Sonohysterography

INTRODUCTION

Ultrasonography is an invaluable diagnostic tool for the assessment of uterine and pelvic pathology.1 The use of both transabdominal and transvaginal ultrasonography has become widespread because it is a safe, noninvasive, and readily available tool in the office setting. For evaluation of uterine cavity abnormalities, the diagnostic accuracy of ultrasonography is improved considerably by injecting normal saline solution into the uterine cavity during a procedure referred to as sonohysterography. For many conditions and complaints, ultrasonography has become one of the standard first steps in the diagnostic evaluation.

PRINCIPLES OF ULTRASONOGRAPHY

Ultrasound Equipment Parameters

Ultrasound Modes

A recent technologic advance, termed three-dimensional (3D) ultrasonography, uses computer software to combine multiple B-mode images in successive planes into a three-dimensional image that displays volume. If multiple volume images are shown in rapid succession, a motion video is obtained, which is sometimes referred to as 4D ultrasonography, because it shows three dimensions over time.2

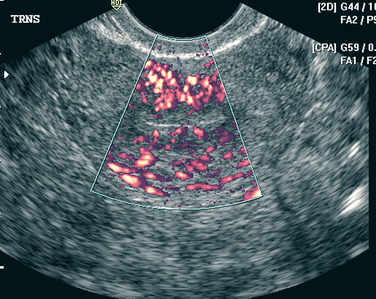

An additional ultrasound approach used clinically is termed color flow Doppler ultrasonography. For this approach, a standard B-mode image is overlaid with colors derived from Doppler sounds, which represent the speed and direction of blood flowing through vessels (Fig. 30-1).

Frequency

Ultrasound frequencies used in gynecology can range from 1.6 to 10 MHz but are more commonly between 3 and 7.5 MHz. These frequencies are much higher than audible sound frequencies, which are less than 20,000 Hz. For ultrasound, lower frequency sound waves are better able to penetrate the body’s tissues more deeply.3 Conversely, higher frequency sound waves give better resolution but penetrate tissue less deeply.

The frequency of most ultrasound probes can be automatically changed by adjusting the depth of the focal zone corresponding to the structure being studied. Ideally, the highest frequency that can penetrate the depth to be studied should be utilized.4

Dynamic Range

Dynamic range is the range between the weakest and the strongest echoes displayed and is expressed in decibels (dB). A broad dynamic range results in the most favorable image characteristics. To minimize artifacts, the dynamic range should be set lower for cystic structures and higher for solid structures.5

APPROACHES

Ultrasonography Versus Sonohysterography

Transvaginal ultrasonography is the first step in evaluating the uterus, ovaries, and tubes. When a symmetric and regular endometrial stripe can be clearly imaged, the uterine cavity can be determined to be normal and endometrial thickness can be accurately determined. In contrast, when the endometrial stripe is irregular or poorly delineated, transvaginal ultrasonography alone has limited usefulness in evaluating the nature and location of endometrial cavity pathology.6–10 In these cases, sonohysterography greatly enhances the ability to visualize lesions that project into the uterine cavity.

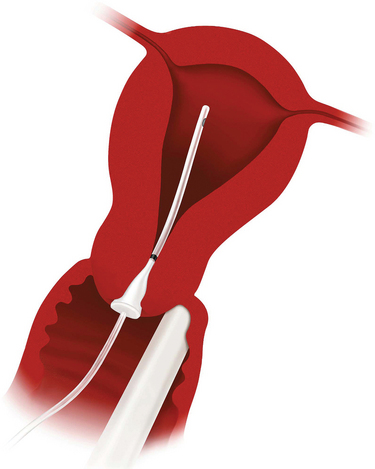

Sonohysterography enhances the diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasonography by filling the endometrial cavity with fluid (usually normal saline solution) via a transcervical catheter.11 First described by Nannini in 1981 as echohysteroscopy, this technique is also referred to as saline infusion sonography.12 Sonohysterography is a simple, accurate way to detect intrauterine masses that will ultimately be evaluated histologically to differentiate endometrial polyps, submucosal leiomyomas, and endometrial carcinoma.13 This technique has several advantages over X-ray hysterosalpingography, including less pain, less cost, and no exposure to ionizing radiation.

INDICATIONS

Transvaginal ultrasound with or without sonohysterography is often one of the first diagnostic steps in the evaluation of a wide spectrum of gynecologic and obstetric conditions that can result from or cause anatomic alterations of the reproductive organs (Table 30-1). The excellent diagnostic accuracy, minimal invasiveness, and relative cost-effectiveness of these techniques have led to their widespread acceptance.

Table 30-1 Clinical Indications for Ultrasonography and Sonohysterography

| Ultrasonography | Sonohysterography | |

|---|---|---|

| Pelvic mass | X | |

| Pelvic pain | X | |

| Pelvic inflammatory disease | X | |

| Lost intrauterine device | X | |

| Infertility | X | X |

| Recurrent pregnancy loss | X | X |

| Abnormal uterine bleeding | X | X |

| To evaluate indistinct endometrium | X | |

| To evaluate thickened endometrium | X | |

| To monitor tamoxifen therapy | X | |

| To predict depth of endometrial cancer invasion | X | |

| Uterine leiomyomata | ||

| Intramural and pedunculated | X | |

| Submucosal and intracavitary | X | |

| Intraoperative sonohysterography | X | |

| To disperse intrauterine adhesions | X | |

Pelvic Mass

Ovarian Masses: Functional, Benign, or Malignant

Certain sonographic characteristics have been found to be strongly associated with malignancy. An ovarian mass is more likely to be malignant when ultrasonography reveals:

These criteria are used in combination with measurements of serum CA 125 for the risk of malignancy index.14 For indeterminate cases, color flow Doppler ultrasonography may also be helpful. It has been demonstrated that ovarian malignancy is more likely if a solid element of the mass demonstrates central blood flow.15

Ovarian Torsion

The sonographic findings for ovarian torsion include a cystic, solid, or complex mass that is frequently found in the midline superior to the uterus.16 This mass, which represents an enlarged ovary, will often have cystic follicles visible along the periphery and a markedly thickened wall. Increased peritoneal fluid is common.

Uterine Leiomyomas

Uterine leiomyomas are the most common indication for hysterectomy in the United States. Although approximately 25% of women will have symptomatic uterine leiomyomas, the cumulative incidence of leiomyomas by age 50 is nearly 70% for white women and more than 80% for black women.17

The classic sonographic appearance of a uterine leiomyoma is a spherical hypoechoic or hyperechoic area contiguous with the uterine wall.18 In some cases, calcification of leiomyomas results in irregular high-amplitude echoes. In many cases, it is difficult with transvaginal ultrasonography alone to determine whether a leiomyoma is intramural, submucosal, or intracavitary in location.

Sonohysterography can accurately identify the size, location, and depth of uterine leiomyomata (Fig. 30-2).19 This information helps predict surgical resectability, the best access for surgery (abdominal versus hysteroscopic), and the duration of surgery.

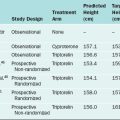

For surgical planning, uterine leiomyomas are classified into three types:

Class 3 leiomyomas are the least amenable to successful resection and are associated with significantly more complications, including uterine perforation, fluid overload, and incomplete resection.20

Pelvic Pain

Pelvic pain is a common gynecologic complaint, accounting for 10% of gynecologic office visits, 40% of laparoscopies, and 15% of hysterectomies in the Untied States.21 Ultrasonography is an important part of the initial workup for patients who present with pelvic pain to identify anatomic causes. In nonpregnant women, ultrasonography can sometimes identify causes, such as hemorrhagic ovarian cysts, ovarian torsion, tubo-ovarian abscesses, or degenerating uterine leiomyoma.

Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Pelvic ultrasonography can be extremely helpful for the evaluation of women with a clinical diagnosis of pelvic inflammatory disease.22 In most patients, ultrasonography will be normal, because normal and inflamed fallopian tubes are not sonographically distinct. Some patients will have acute or chronic abnormalities that are sonographically visible, such as a pyosalpinx, hydrosalpinx, tubo-ovarian abscess, or tubo-ovarian complex (Fig. 30-3).

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Premenopausal Women

Transvaginal ultrasonography is a useful diagnostic test in the premenopausal woman who presents with abnormal bleeding. The vast majority of premenopausal bleeding is the result of anovulatory uterine bleeding. Other common causes include submucosal leiomyoma and endometrial polyps, which can be detected by ultrasonography with sensitivity of approximately 94% and 80%, respectively.23 In women with abnormal bleeding after an abortion or delivery, ultrasonography can sometimes determine the cause of abnormal bleeding to be retained products of conception.24,25 Endometrial cancer is an uncommon cause of bleeding in women younger than age 40.

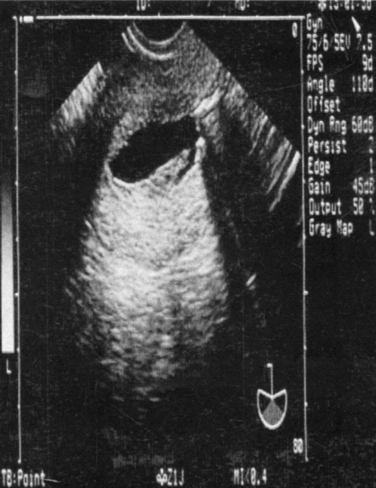

Endometrial thickness is not very discriminatory in premenopausal women. This is in contrast to postmenopausal women, in whom endometrial thickness greater than 5mm is cause for concern. During a normal menstrual cycle, endometrial thickness normally varies from 5 to 12mm.26,27 Sonohysterography can be extremely helpful in these cases.

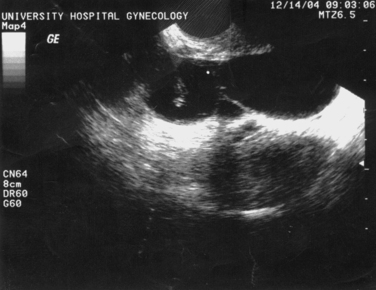

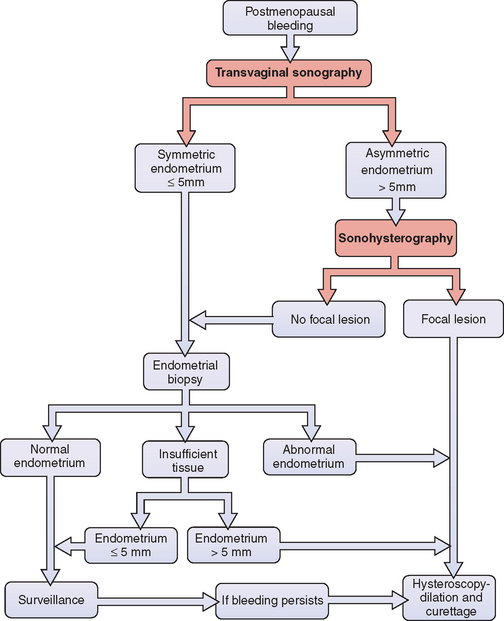

Postmenopausal Women

Evaluation of abnormal uterine bleeding in postmenopausal women is extremely important to exclude endometrial cancer, because almost 10% will ultimately be found to have a malignancy.28 Endometrial cancer occurs in 1 to 2 per 1000 postmenopausal women per year and is one of the most common cancers in the female, exceeded in frequency only by cancers of the breast, colon, and lung. Thus, all postmenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding should undergo a thorough evaluation.

Evaluation of Abnormal Uterine Bleeding

Suction sampling devices are useful for detecting global disease but frequently are inadequate for detecting disease localized to a focal area or a polyp. Studies demonstrate that 15% or less of the endometrial cavity is sampled using suction devices.29 Although sampling with a suction device will provide adequate tissue for pathologic evaluation in as many as 97% of cases, carcinoma confined to endometrial polyps and localized tumors will be missed more than 15% of the time.30 For this reason, many clinicians advocate sonographic evaluation of the endometrium before endometrial biopsy to exclude focal lesions.

Ultrasonography Versus Sonohysterography

Ultrasonography and sonohysterography are sensitive noninvasive methods for detecting focal intrauterine lesions, which usually indicate carcinoma, hyperplasia, polyps, and submucosal uterine fibroids.31–36 The incidence of polyps and submucosal uterine fibroids in symptomatic premenopausal women is 33% and 21%, respectively.37 If ultrasonography or sonohysterography reveals a focal lesion, this should be evaluated with a hysteroscopy/D&C rather than with a blind endometrial biopsy, because ultrasonography cannot accurately identify the nature of the lesion.

Several studies have suggested that in postmenopausal women, endometrial thickness up to 5 mm makes endometrial pathology (i.e., endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma) extremely unlikely, and some clinicians will therefore omit an endometrial biopsy.38 This cutoff is only useful in postmenopausal women who are not taking postmenopausal hormones such as estrogen or tamoxifen. It is also important to remember that using sonographic thickness of the endometrium to exclude endometrial carcinoma in postmenopausal women with bleeding is not 100% accurate regardless of the cutoff used.

How accurate is endometrial thickness in predicting carcinoma? Meta-analyses indicated that carcinoma will be found in approximately one third of postmenopausal women with bleeding whose endometrial thickness is greater than 5mm.39 When the endometrium is equal to or less than 5mm, only 2% to 7% will subsequently be found to have carcinoma.39,40 Reducing the cutoff to 4mm will decrease the risk of carcinoma to 1.2%.41 Because endometrial carcinoma is a curable disease when discovered early, most clinicians will perform an initial endometrial biopsy in postmenopausal women with bleeding, regardless of endometrial thickness (Fig. 30-4). If the biopsy of a patient with an endometrial thickness of 5mm or less returns as “quantity not sufficient for diagnosis,” continued surveillance is a reasonable approach.

Sonohysterography

Sonohysterography is much more effective than transvaginal ultrasound alone to detect endometrial pathology in women with abnormal uterine bleeding and thickened endometrium. In addition to clearly demonstrating the location of intracavitary lesions, sonohysterography allows for differentiation of isolated submucosal defects from more diffuse endometrial thickening.19,42–44 One study of 199 postmenopausal women with abnormal bleeding found that whereas only 7% were found to have endometrial abnormalities on transvaginal ultrasound, more than 34% had abnormalities detected by sonohysterogram.45

In the past, the initial step in the evaluation of a woman with postmenopausal bleeding was an office endometrial biopsy. However, this procedure is notoriously inaccurate in the presence of focal endometrial pathology. In one study, 148 postmenopausal women with abnormal bleeding underwent aspiration endometrial biopsy, followed by sonohysterography whenever the endometrial thickness was greater than 5mm.46 Sonohysterography discovered 45 focal lesions in 81 women, 5 of which were determined to be malignancies by hysteroscopy. The initial endometrial biopsy missed 41 of these focal lesions and 3 of the 5 malignancies. The take-home message is that a blind endometrial biopsy should be avoided in women determined to have focal lesions because they often miss the pathology.

Sonohysterography is as accurate as hysteroscopy for the detection of focally growing lesions, with sensitivities for both of approximately 96%.47 However, neither modality can reliably discriminate between benign and malignant focal lesions. For this reason, histologic tissue evaluation is required whenever intrauterine pathology is discovered.

The evaluation of postmenopausal women with abnormal bleeding should utilize a combination of transvaginal ultrasonography, sonohysterography, or office endometrial biopsy when indicated, and hysteroscopy for women found to have focal lesions or abnormal biopsies (see Fig. 30-4). Utilizing ultrasonography before endometrial biopsy will avoid this uncomfortable test in women found to have focal lesions because they require a directed biopsy instead. This combination of sonohysterography and endometrial biopsy has been found to have a sensitivity of 97%, a specificity of 70%, a positive predictive value of 82%, and a negative predictive value of 94%.46

Breast Cancer Patients Receiving Tamoxifen

Tamoxifen, a selective estrogen receptor modulator, is a commonly used adjunctive therapy for women with breast cancer. Although tamoxifen acts as an estrogen antagonist in the breast, it acts as an estrogen agonist in the genital tract and is associated with endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma. Patients taking tamoxifen have a 27% risk of developing endometrial polyps, a 9% risk of endometrial hyperplasia, and a rate of endometrial cancer two to three times higher than that of age-matched women.48,49

Neither transvaginal ultrasonography nor sonohysterography are effective screening tools in women using tamoxifen because of tamoxifen-induced subepithelial stromal hypertrophy.50–52 As a result of this abnormality, there is a poor correlation between ultrasonographic measurements of endometrial thickness and abnormal endometrial proliferation or endometrial carcinoma.53–55 Women taking tamoxifen should be monitored for symptoms of endometrial hyperplasia or cancer (e.g., abnormal uterine bleeding) and undergo a gynecologic examination at least yearly.56 However, because ultrasonographic screening has not been found to be effective, it is not recommended.

When a women taking tamoxifen experiences abnormal uterine bleeding, sonohysterography appears to be the most appropriate next step.57 Surgery can be avoided in approximately 14% of women who will be found to have normal endometrium with or without subendothelial cysts. The remainder of women will have focal lesions and should undergo hysteroscopically directed biopsies, because a blind endometrial biopsy in the office will often miss lesions.57

Screening of Asymptomatic Women

Premenopausal Women

Some clinicians recommend screening asymptomatic women with transvaginal ultrasonography, sonohysterography, or endometrial biopsy.58 One study found that approximately 10% of asymptomatic premenopausal women have uterine polyps and 1% have intracavitary fibroids, compared to 33% and 21% of symptomatic women, respectively.59 However, it is uncertain how much of this pathology is actually associated with health risks and how much will regress spontaneously.60 The concern is that such screening is likely to lead to some unnecessary surgical intervention. Until more information is available, universal screening is not recommended.61

Postmenopausal Women

Transvaginal ultrasound has not been shown to be a useful screening test in asymptomatic postmenopausal women regardless of their use of hormone treatment. One study reported that more than 35% of asymptomatic postmenopausal women have focal endometrial pathology by sonohysterography.45 Although the incidence of endometrial pathology in postmenopausal women with bleeding is relatively high, the incidence of life-threatening focal endometrial lesions in asymptomatic women is likely to be low.61 More importantly, the discriminatory value of endometrial thickness is lost in these asymptomatic women. One study of 448 postmenopausal women, half of whom were receiving estrogen replacement therapy, found that although endometrial thickness less than 5 mm was highly predictive of normal endometrium (negative predictive value, 99%), endometrial thickness greater than 5 mm was unlikely to indicate pathology (positive predictive value, 9%).60 A study of 1926 asymptomatic postmenopausal women showed similar results using a 6 mm threshold for endometrial thickness.63 Screening asymptomatic postmenopausal women is not currently recommended.

Endometrial Carcinoma

Detecting Endometrial Carcinoma

Sonography and sonohysterography can detect abnormalities of the endometrium but cannot accurately distinguish between malignant and benign lesions. With transvaginal ultrasonography, endometrial carcinoma usually appears to be either diffusely or partially echogenic. With sonohysterography, endometrial carcinoma appears as irregularly thickened endometrium or a discrete mass, but is indistinguishable from endometrial hyperplasia.11,42 A poorly distensible endometrial cavity noted during sonohysterography can be a sign of endometrial cancer.64 In the case of polyps, Doppler flow ultrasonography is of little help in distinguishing between the majority of benign polyps and those that are malignant.65

Predicting Depth of Invasion

Histology, tumor grade, depth of myometrial invasion, and tumor size are well known prognostic factors for lymph node metastasis by endometrial cancer but are difficult to predict preoperatively.66,67 Magnetic resonance imaging is effective in predicting the depth of myometrial invasion and endometrial cancer tumor size but is expensive and is not universally available. An alternative approach is sonohysterography to determine the depth of endometrial invasion; patients with deeply invasive disease can be referred to a gynecologic oncologist.

After endometrial carcinoma has been diagnosed histologically on biopsy, sonohysterography has been suggested as a way to accurately determine the degree of myometrial invasion.68 In a small study of 19 endometrial adenocarcinoma patients, sonohysterography performed before hysterectomy was able to predict the exact depth of myometrial invasion in 15 (94%) cases, suggesting a potential role for this technique in preoperative staging of endometrial carcinoma. More studies are necessary before widespread application of this approach.

Risk of Disbursing Malignant Cells

There is a concern that procedures that distend the uterus with fluid media (i.e., hysteroscopy, hysterosalpingography, and sonohysterography) could flush malignant endometrial cells into uterine vessels or through the tubes into the peritoneal cavity, thus adversely affecting the prognosis for patients with endometrial carcinoma. One study of hysterograms in patients with endometrial cancer found no correlation between intravasation of contrast medium into lymphatics and veins and subsequent 5-year survival rates.69 A sonohysterogram study of women with stage I endometrial carcinoma showed that infusion of 10 to 20mL of saline solution resulted in saline spillage from the fallopian tubes in 5 of 14 patients; in 1 patient this fluid contained malignant cells.70 These findings suggest that sonohysterography might have a small risk of cancer dissemination, although the prognostic significance of flushing endometrial cancer cells in the peritoneal cavity remains uncertain. Additional studies are warranted.

Infertility and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss

Initial Evaluation

Transvaginal ultrasonography, with sonohysterography when indicated, is a useful diagnostic procedure for the initial evaluation of infertile patients.71 Congenital and acquired uterine pathology is present in up to 10% of infertile couples and 15% to 55% of those with recurrent pregnancy loss. Pathologic conditions of the uterus that can be detected with ultrasonography and sonohysterography include müllerian and diethylstilbestrol-related anomalies, uterine fibroids, endometrial polyps, and Asherman’s syndrome. Other fertility-related conditions that can be detected include hydrosalpinges (see Fig. 30-3) and polycystic ovaries (Fig. 30-5).

Sonohysterography can be used to thoroughly evaluate the endometrial cavity and has been shown to be as accurate as diagnostic hysteroscopy in detecting pathology. In a study of 72 infertile women, 11% were found to have cavitary lesions with both HSG and hysteroscopy; there was no statistical difference in pregnancy outcome between these two techniques for uterine evaluation.72

Recurrent Pregnancy Loss

The diagnosis and surgical correction of uterine defects associated with recurrent pregnancy loss increases the rate of full-term delivery. Anatomic disorders, including congenital müllerian anomalies and acquired defects such as uterine leiomyomata and uterine synechiae, account for 15% to 55% of recurrent pregnancy loss.73

Prior to the development of ultrasonography, HSG was the diagnostic test of choice for uterine anomalies. However, HSG is not effective in assessing the outer uterine contour, and thus cannot accurately discriminate between a septate and a bicornuate uterus.73,74 In the case of uterus didelphys with a complete vaginal septum covering one of the two cervical openings, cannulation of only one cervical canal during HSG can lead to the misdiagnosis of a unicornuate uterus.75

Transvaginal ultrasonography is more accurate than HSG in diagnosing müllerian anomalies, because it can detect structures not visible externally, such as noncommunicating uterine horns, and can determine both the internal and external contours of the uterus.76 An important function of ultrasonography is to differentiate between a uterine septum and a bicornuate uterus (Fig. 30-6). The diagnosis of bicornuate uterus is made in the presence of fundal notch deeper than 1 cm, diverging endometrial cavities, and fundal broadening of the intracavitary tissue, which is typically thick and isoechoic relative to the rest of the myometrium.77 A uterine septum is usually thinner and hypoechoic because it tends to be more fibrous. However, hypoechogenicity is not diagnostic, because the septum can contain both fibrous and muscular elements.78

Sonohysterography appears to be an even better screening tool in patients with a history of recurrent pregnancy loss, and in one study was twice as accurate as either HSG or ultrasonography alone.74 Sonohysterography has been reported to demonstrate a variety of other uterine cavity defects, including müllerian anomalies, in up to 50% of these patients.79

Three-dimensional (3D) ultrasonography has been shown to be useful in the diagnosis of müllerian anomalies.80 The presence of leiomyomas can obscure the view and decrease the sensitivity of 3D ultrasound. The best image is obtained when the scan is performed during the luteal phase. A normal external fundal contour or one with less than 10 mm indentation is consistent with a septate uterus.

Fallopian Tube Evaluation

Sonosalpingography has been used to determine tubal patency by sonographically observing saline or sonographic contrast media as it traverses the tubes. Some studies have shown this technique to be as accurate as HSG in determining tubal patency, especially when used in conjunction with Doppler ultrasound.81

If there is any doubt about tubal spill, a solution that enhances sonographic contrast can be used. Human albumin (Albunex, Mallinckodt, St. Louis) or lactose particles suspended around microbubbles (Echovist, Schering, Berlin) provide excellent sonographic contrast to document tubal patency and spillage.82 The safety of Albunex has been established in multiple studies, but it should only be used in selected cases secondary to cost and refrigeration storage requirements.

Air bubbles can also be used as an inexpensive and reasonably accurate first-line sonographic contrast to determine tubal patency.83 After the uterine cavity is evaluated with saline solution, small amounts of air are insufflated. These bubbles are easily seen sonographically. Air-contrast sonohysterography and laparoscopy showed agreement in 79.4% of patients, with a sensitivity of 86% and specificity of 77.2%.

Before Assisted Reproductive Technologies

Many fertility centers also evaluate all patients with sonohysterography before embryo transfer subsequent to IVF. The detection of cervical pathology before starting the cycle is important, because difficult embryo transfer adversely affects outcomes in women undergoing IVF.84 Likewise, preexisting intrauterine pathology that might decrease subsequent pregnancy rates can be detected and treated. In one study, 80 women planning to undergo IVF with ovum donation were prescreened with sonohysterography; 38% were found to have pathology subsequently confirmed at hysteroscopy.85

Controlled Ovarian Hyperstimulation and In Vitro Fertilization

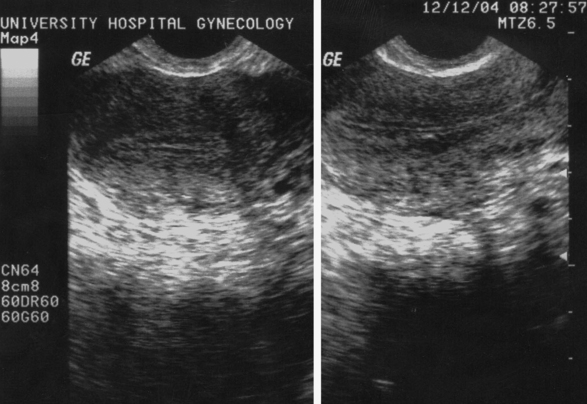

Endometrial thickness and pattern determined sonographically can also predict subsequent pregnancy outcomes. Endometrial thickness greater than 6 mm has been associated with higher implantation and pregnancy rates and lower miscarriage rates in some studies.86,87 However, this relationship remains controversial, because other studies have reported no predictive value of endometrial thickness.88–92 Sonographic endometrial patterns are also important. Proliferative endometrium appears as a triple layer (Fig. 30-7). There are three distinct regions: the central echogenic line, the outer hyperechoic line, and the hypoechoic region between the two lines. In the luteal phase, the endometrium becomes uniformly hyperechoic (Fig. 30-8). A hyperechoic endometrium immediately before ovulation is associated with a lower pregnancy rate. The multilayered pattern is clearly associated with a higher pregnancy rate.88

A final use of sonography in IVF is for embryo transfer. A large, prospective, randomized study found that the pregnancy rate was significantly higher among the ultrasound-guided group (50%) compared with the clinical touch group (34%).93 Today, most IVF programs utilize this approach.

Pregnancy

Viability and Location

It is important to establish the number of viable embryos in women who have been treated with oral or injectable medications to induce ovulation or who have undergone transfer of multiple embryos after IVF. These assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) are associated with multiple gestation rates ranging from 5% to 35%, depending on the specific approach used.

Other Therapeutic Application

Operative Sonohysterography

Ultrasound-directed biopsy for submucosal pathology has been reported as a cost-effective alternative to hysteroscopy. One technique involves insertion of a #3 French loop or finger-like grasper through an access catheter under sonohysteroscopic guidance.94 This approach is hampered by the instrument’s small size and limited rotational ability.

Another technique uses a loop snare to resect intrauterine abnormalities under sonohysteroscopic guidance.95 For this technique, a #12 French intrauterine access catheter with a 3-mL balloon (Cook OB/GYN, Spencer, Ind.) is placed through the cervical canal. A #5 French echogenic loop snare is then passed through the access catheter to perform the resection mechanically. The reported time required for resection of polyps ranged from 18 to 43 minutes. This technique is difficult in patients with cervical stenosis, which precludes insertion of the operative instruments, and for removal of cornual lesions. More research is required before widespread clinical application of these techniques.

Tubal Cannulation during Sonosalpingography

Some therapeutic procedures may be possible during sonosalpingography. One report details hysteroscopic proximal tubal cannulation with concomitant intraoperative ultrasound-guided visualization of the fallopian tubes using Albunex after having failed fluoroscopic cannulation.41 In select cases, this could obviate the need for laparoscopy.

Intraoperative Sonohysterography

Ultrasonography can be used as an intraoperative aid for multiple transvaginal procedures, many of which had to be done blindly in the past.96–98 During difficult dilations secondary to cervical stenosis and during hysteroscopic resection of extensive intrauterine synechiae, sonographic visualization of the uterus can decrease the risk of uterine perforation. Likewise, during uterine curettage for spontaneous and induced abortion, ultrasonography can be used to prevent or detect uterine perforation and to ensure complete removal of the products of conception. During the hysteroscopic removal of impacted foreign bodies (e.g., intrauterine devices), ultrasonography can locate the foreign body and decrease the risk of perforation. Finally, for intracavitary radiation treatment of endometrial cancer, ultrasonography can aid in the correct placement of the intrauterine tandem apparatus.

Sonohysterography can also be used as an interoperative adjunct during operative hysteroscopy and laparotomy. The most common uses may be to ensure complete removal of deep intramural myomas adjacent to the endometrial cavity, to decrease the chance of uterine perforation during intrauterine resection, and to clarify confusing visual findings during hysteroscopy.41

Pressure Lavage under Ultrasound Guidance

Pressure lavage under ultrasound guidance (PLUG) has been described in a series of seven patients as method for the treatment of secondary amenorrhea due to intrauterine adhesions.99 Continuous transcervical injection of saline solution was used to mechanically disrupt these intrauterine adhesions. This technique satisfactorily disrupted mild adhesions in five patients but was unable to disrupt moderate adhesions in two patients. Menses were restored in all seven patients, and two of the three previously infertile patients attempting pregnancy were successful. Further controlled studies are needed to determine the relative value of this approach.

RISKS

The long-term effects of ultrasound during pregnancy continue to be closely scrutinized because the developing brain is the tissue most vulnerable to biologic damage. Fortunately, no study to date has been able to detect impaired neurologic development in children exposed to prenatal ultrasound.100

Sonohysterography has the potential risks of infection, bleeding, and perforation associated with introduction of instruments (catheters) and media (usually sterile saline solution) into the uterine cavity. The risk of infection after sonohysterography has been reported to be less than 1%, and no cases of serious bleeding or perforation have been reported.101

TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Timing in the Cycle

Pelvic ultrasonography is performed throughout the menstrual cycle, depending on indication. However, when searching for endometrial defects, it is important to scan during the follicular phase when the endometrium is hypoechoic and will serve as a contrast to echogenic polyps and fibroids. During the luteal phase, the endometrium assumes the same echogenicity as polyps, and this contrast disappears.102

Sonography can be performed in the presence of uterine bleeding, where the blood sometimes provides a good endometrial–myometrial interface referred to as a spontaneous sonohysterogram.13 Unfortunately, blood or clots can also be misinterpreted as pathology such as polyps or adhesions; thus it is recommended to avoid the procedure if possible when a patient is bleeding heavily.103 If the study is performed during bleeding and small lesions (<10mm) are seen, repeating the examination during a bleeding-free interval is advisable.

Vaginal Ultrasonography

During the reproductive years, ovaries can usually be identified by their typical follicular appearance. The normal functioning ovary often has multiple preantral follicles 2 to 10mm in diameter. Multiple preantral follicles along the outer edge of the ovarian cortex (string of pearls pattern) is often seen in women with polycystic ovary syndrome but can also be seen in up to 10% of women who appear to be ovulating regularly (see Fig. 30-5).104 The number of visible preantral follicles count correlates with subsequent ovarian response to controlled ovarian hyperstimulation.105 Transitory simple or complex ovarian cysts up to 6 cm in diameter often represent functional cysts, including persistent unruptured follicles and corpora lutea cysts.

Sonohysterography

Catheter Choices

Catheter choices differ according to stiffness, presence or absence of a balloon, and cost.106 The simplest catheter is a semirigid #5 French pediatric feeding tube. A similar device equipped with a cone designed to partially occlude the external os is the Goldstein sonohysterography catheter (Cook Ob/Gyn, Spencer, Ind.), which has been associated with the least patient discomfort in one study (Fig. 30-9).106 Patients with latex allergy can be safely evaluated with the H/S Elliptosphere catheter with latex-free urethane (Akrad Laboratories, Cranford, N.J.) (Fig. 30-10).

Figure 30-10 H/S Elliptosphere catheter with latex-free urethane. (Cooper Surgical Inc., Turnbull, Ct.)

A balloon catheter is sometimes required to allow adequate distension of the endometrial cavity in patients with patulous or incompetent cervices or those with enlarged uteri.107 The least expensive balloon catheter is a #8 French pediatric Foley catheter, but it is also the most difficult to correctly place because of its lack of stiffness. A #5 French catheter with a 2-mL balloon is commercially available from several companies. Using a balloon catheter results in discomfort not unlike that experienced with an HSG, related both to the intracervical balloon and the distension of the uterus. Pretreatment with NSAIDs will minimize this discomfort.

Cervical stenosis presents a special challenge when placing the catheter. In many patients, all that is required is the use of a tenaculum to place countertraction on the cervix. In more difficult cases, the catheter can be stiffened with the use of a guidewire.108

Procedure

As the fluid is slowly injected, the uterus should be scanned in the longitudinal plane fanning from one cornu to the other and in the transverse plane from the top of the fundus to the cervix. Only 2 to 5mL is required to distend the uterine cavity in most women. However, because of cervical leakage (especially when a balloon is not used), from 5 to 20mL of fluid are actually used during the procedure. For this reason it is ideal to have a full 20- or 50-mL syringe filled with the selected fluid at the beginning of the procedure, with more in reserve. Inadequate distension may result in poor visualization, whereas overzealous distension may increase pain and obscure pathology.13,103

Common Problems

Common problems seen with this procedure include the following:

SONOGRAPHIC FINDINGS

Normal Findings in the Uterus and Ovaries

Reproductive-Age Women

The uterus and ovaries of a reproductive-age woman are dynamic organs that undergo cyclic changes each month. Ultrasonography provides an information window to normal and abnormal physiologic changes, including synchrony between ovarian findings and normal endometrium.109,110

During the proliferative phase, estrogen stimulation causes the endometrium to appear as a triple layer, where the central echogenic line represents the uterine cavity, the outer lines represent the interface of the basal layer of the endometrium and the myometrium, and the relatively hypoechoic regions between these layers represent the functional layer of the endometrium (Fig. 30-12).111,112

A dominant follicle can be seen developing in the ovary as early as day 8 to 9 of the cycle. This simple cystic structure will exponentially grow to 20 to 25 mm in diameter and spontaneously rupture at the time of ovulation at around midcycle (Fig. 30-13).102,109 Free fluid in the cul-de-sac is highly suggestive that ovulation has occurred.

During the postovulatory secretory phase, endometrial growth typically plateaus 5 days after the LH surge, reaching an average diameter of 14 mm. Progesterone exposure causes the previously hypoechogenic endometrium to transition to a homogeneous and echogenic pattern by the midluteal phase (see Fig. 30-8).111 These changes are related to the interface among luteal phase secretions, increased vascularity, and stromal edema.20

A corpus luteum will usually be visible in one of the ovaries during the secretory phase. It appears as a thick-walled, irregular structure sometimes containing internal echoes corresponding to blood and debris (Fig. 30-14). This finding can be difficult to differentiate from an endometrioma or neoplasm and often requires repeat scanning in the following follicular phase.

Myometrial contractions that appear as waves in the endometrium can sometimes be seen with real-time ultrasonography. These contractions appear to progress from the cervix to the fundus in the late follicular phase and have been shown to increase in frequency and intensity around ovulation. In the luteal phase, these contractions are less pronounced. Some infertile women, especially those with endometriosis, appear to have hyperperistalsis and disorganized, nondirectional waves at midcycle.113–115 This has been hypothesized to result in sperm transport abnormalities and the spread of peritoneal endometriosis.

The normal, nondistended fallopian tube is difficult to visualize sonographically due to its small diameter.116 On transverse views of the uterus, the origin of the fallopian tubes can sometimes be appreciated by following the invagination of the endometrium from the cornual region, which represents the tubal ostia, laterally into the adnexal region. Intraperitoneal fluid can sometimes enhance visualization of the fallopian tubes.117

Transvaginal ultrasound is a sensitive method of detecting the presence of free pelvic fluid; therefore, it is an important diagnostic tool in the assessment of pelvic pathology associated with increased peritoneal fluid.118 Free fluid is normally found in the female pelvis. The smallest amount consistently detected by transvaginal ultrasound is 8 mL. Typically 2 to 9 mL are found under normal physiologic circumstances.

Pelvic ultrasonography depicts other pelvic structures, including loops of bowel and pelvic blood vessels. The internal iliac arteries are typically between 5 and 7mm in transverse diameter and pulsate, whereas the iliac veins are larger (approximately 1cm in diameter) but do not pulsate.

Postmenopausal Woman

In contrast to normal reproductive-age women, postmenopausal woman not taking replacement hormones do not have cyclic changes in the reproductive organs. Transvaginal ultrasound measurement of endometrial thickness is routinely used to evaluate abnormal vaginal bleeding and has been used as a biomarker for estrogen exposure.59 The endometrium of hypoestrogenic women has a fine, thin linear echogenicity with an intact hypoechoic zone surrounding it, usually less than 5mm thick. Increased estrogens, either exogenous (i.e., from hormone therapy) or endogenous (i.e., from obesity, diabetes, and hypertension), are associated with an increased endometrial thickness and risk of endometrial cancer.

Some postmenopausal women will exhibit adnexal findings, and up to 3% will have unilocular ovarian cysts. Approximately 85% of simple ovarian cysts are epithelial in origin, and few ultimately prove to be malignant. Unilocular ovarian cysts less than 10mm in diameter in asymptomatic postmenopausal women are unlikely to represent ovarian cancer, close to 50% spontaneously resolving within 60 days. In contrast, complex ovarian cysts with wall abnormalities or solid areas are associated with a significant risk for malignancy.119

Uterine Pathology

Leiomyoma

Ultrasound can localize fibroids as submucosal, intramural, or subserosal. Fibroids typically appear as well-circumscribed, hypoechoic masses that usually contain calcium or rarely fat and often undergo cystic degeneration and develop cystic or hemorrhagic areas. Small submucosal fibroids can cause focal hypoechoic indentation on the endometrial stripe. Pedunculated fibroids can be confused with solid adnexal masses, but identification of both ovaries separate from the mass can help establish a correct diagnosis. Doppler color ultrasound can usually identify a blood vessel that arises from the uterus to supply the myoma.30

Adenomyosis

Adenomyosis is the presence of ectopic endometrial glands in the myometrium surrounded by hypertrophied smooth muscle. With careful examination, this condition can be detected in 8% to 30% of hysterectomy specimens. It typically affects the uterus in a diffuse manner, but focal disease can be present in the form of an adenomyoma. Ultrasound imaging can reveal diffuse uterine enlargement without focal abnormality, diffuse posterior myometrial thickening, or myometrial sonolucencies.121

Müllerian Duct Anomalies

Müllerian duct anomalies represent a wide spectrum of abnormalities resulting from failure of development, fusion, or resorption of the paired müllerian ducts and occur in up to 5% of the general population. The most common of these anomalies are arcuate, septate, and bicornuate uteri.122

During ultrasonography, coronal imaging of the uterine fundal and endometrial contour is critical in differentiating a septum from a bicornuate uterus.123 A septum is diagnosed when a tissue band is seen separating two endometrial cavities in the absence of a fundal notch. A septum will usually appear as a hypoechoic band, because a septum is usually predominantly fibrous. A muscular septum will have the same echodensity as the myometrium.

Endometrial Abnormalities

Endometrial Masses

Small lesions that project into the cavity, distortions of the uterine anatomy, and the phase of the menstrual cycle often pose challenges in precisely diagnosing endometrial pathology.7–9 Sonohysterography is essential for defining the location of the pathology where myomas typically originate from the myometrium, whereas polyps are contained within the endometrial cavity. Abdominal and transvaginal ultrasonography alone have limited usefulness in evaluating the exact location of endometrial cavity pathology.6

Intrauterine Adhesions

Intrauterine adhesions are suggested on ultrasonography by subtle alterations in the endometrial thickness and homogeneity and changes in the sharpness of the endometrial–myometrial interface.124 The instillation of fluid contrast into the endometrial cavity during sonohysterography provides an interface to greatly enhance the detection of these adhesions.

Adnexal Pathology

Ovaries

Two of the most common benign complex masses are dermoid cysts (benign cystic teratomas) and endometriomas. Dermoid cysts can have many appearances that can range from completely cystic in appearance to a complex mass with hyperechoic solid elements (Fig. 30-15). These usually represent hair, fatty material, and occasionally teeth within the dermoid.

Endometriomas are cystic ovarian structures that sonographically have a typical “ground glass” appearance characterized as homogeneous, low-level echoes in 90% of cases.64,125 Septations are seen in 29% of cases and fluid levels are present in 5%. These classic sonographic findings are not specific and can also be seen with hemorrhagic corpus luteum, ovarian abscess, dermoids, cystadenomas, and carcinomas.126,127

Early Pregnancy Ultrasound

In early pregnancy, a blastocyst burrows into the decidualized endometrium and forms an amniotic cavity, a bilaminar embryonic disk, and the primary yolk sac.128 Proliferation of the trophoblast produces primary chorionic villi. Sonographically, the gestational sac is an echogenic ring surrounding a sonolucent center. It is the result of a trophoblastic decidual reaction that occurs as the primary villi invade maternal decidua.

The yolk sac is visible sonographically at about 3 to 3½ weeks postconception (5 to 5½ weeks’ gestation), although it has been present since the blastocyst stage and implantation.129 It is fetal in origin, but extra-amniotic and about 4mm in diameter. It appears as a thin and bright echogenic rim around a sonolucent center. It will remain for up to 10 weeks and eventually is incorporated beneath the amnion. It often precedes visualization of the embryo by 3 to 7 days and is reassuring until a fetal or embryonic pole with cardiac activity can be detected.130 Identification of fetal cardiac activity after 8 weeks’ gestation is associated with a pregnancy continuation rate of more than 95%.

Ectopic Pregnancy

The discriminatory zone is an important concept first described by Kadar and colleagues in 1981.131 The discriminatory zone represents the level of serum β-hCG at which an intrauterine gestational sac can be seen by ultrasonography. Using transvaginal ultrasonography, the discriminatory zone β-hCG level is generally accepted to be 2000mIU/mL for a singleton pregnancy, although some clinicians use a β-hCG level as low as 1000 mIU/mL.132–135 It is important to remember that the discriminatory zone for an individual patient may be increased according to the type of sonographic equipment available, the experience of the ultrasound technologist, the presence of multiple intrauterine pregnancies, and pathology such as uterine leiomyomas, which may limit visualization of the gestational sac. However, when an intrauterine pregnancy cannot be definitely visualized by transvaginal ultrasonography with a β-hCG level greater than 2000 mIU/mL, an ectopic pregnancy should be suspected.

The initial step in the evaluation of a patient at risk for ectopic pregnancy is to look for evidence of an intrauterine pregnancy. Although an intrauterine pregnancy does not absolutely exclude the possibility of an ectopic pregnancy, heterotopic pregnancies are rare. An exception is after application of ART, where heterotopic pregnancy is estimated to occur in 1% of subsequent pregnancies.136

An early intrauterine pregnancy is characterized sonographically as a gestational sac within the endometrial cavity, which is described as a hyperechoic trophoblastic decidual ring around the sonolucent chorionic cavity. An ectopic pregnancy can be associated with a pseudogestational sac on ultrasonography, which can be difficult to distinguish from a true intrauterine gestational sac. A pseudogestational sac is described as a fluid collection, usually irregular in shape, that is found close to the endometrial cavity line.137

A normal intrauterine gestational sac is visible on transvaginal ultrasonography approximately 32 to 36 days after an accurate last menstrual period, and the sac grows approximately 1mm/day in mean diameter during early pregnancy.131,138 A yolk sac should be visible in most pregnancies when the gestational sac measures 8mm, and definitely by 10mm or approximately 5 weeks’ gestation. The embryo appears as a thickening along the edge of the yolk sac. The growth rate of the embryo is 1mm/day, and fetal cardiac activity within the fetal pole can be detected with a gestational sac measurement of 18mm or larger.139,140

Evaluation of the adnexa by transvaginal ultrasonography is of paramount importance in the patient with suspected ectopic pregnancy, especially in the absence of a visible intrauterine gestational sac (see Fig. 30-16). The most convincing finding of an ectopic pregnancy is a gestational sac in the adnexa, with or without a yolk sac or fetal pole. Approximately 85% of the time, the ectopic pregnancy will be found on the same side as the corpus luteum.

Figure 30-16 Ectopic pregnancy. Typical hyperechoic trophoblastic “tubal” ring without myometrium around the gestation.

The early sonographic appearance of the ectopic pregnancy is the presence of a hyperechoic trophoblastic “tubal” ring, with no myometrium around the gestation. If color flow Doppler ultrasonography is available, the increased blood supply around the trophoblastic ring can be demonstrated. The finding of fluid in the cul-de-sac in the absence of an intrauterine pregnancy increases the likelihood of an ectopic pregnancy.63

Ninety-five percent of ectopic pregnancies are located in the fallopian tube. A cornual (interstitial) pregnancy is diagnosed when a gestational sac is visualized sonographically more than 1cm away from the most lateral aspect of the uterine cavity surrounded with a thin layer of myometrium.141 Rarely, a cervical pregnancy is diagnosed when a gestational sac in seen in the cervix but should not be confused with an intact gestational sac passing through the cervix. Ovarian and abdominal pregnancies are even rarer, and transvaginal ultrasonography is often essential in making these diagnoses.

CONCLUSION

1 Dubinsky TJ, Parvey R, Gormaz G, et al. Transvaginal hysterosonography: Comparison with biopsy in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. J Ultrasound Med. 1995;14:887-893.

2 Timor-Tritsch IE, Goldstein SR. Ectopic pregnancy. In: Goldstein SR, Timor-Tritsch IE, editors. Ultrasound in Gynecology. New York: Churchill Livinstone; 1995:31-47.

3 Thornton KL. Principles of ultrasound. J Reprod Med. 1992;37:27-32.

4 Laing FC, Brown DL, DiSalvo DN. Gynecologic ultrasound. Radiol Clin North Am. 2001;39:523-540.

5 Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A. Scanning techniques in obstetrics and gynecology. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1996;39:167-174.

6 Laifer-Narin SL, Ragavendra N, Lu ASK, et al. Transvaginal saline hysterosonography: Characteristics distinguishing malignant and various benign conditions. Am J Radiol. 1999;172:1513-1520.

7 Lindheim SR. Sonohysterography: Nascent applications. OBG Management. 1997:23-26.

8 Graham D, Chung SN. Office sonohysterography. Adv Obstet Gynecol. 1997;4:137-141.

9 Chung PH, Parsons AK. A practical guide to using saline infusion sonohysterography. Contemp Obstet Gynecol. 1997;42:21-24.

10 Ayida G, Chamberlain P, Barlow D, Kennedy S. Uterine cavity assessment prior to in vitro fertilization: Comparison to transvaginal scanning, saline contrast hysterosonography and hysteroscopy. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1997;10:59-62.

11 Parsons AK, Lense JJ. Sonohysterography for endometrial abnormalities: Preliminary results. J Clin Ultrasound. 1993;21:87-95.

12 Nannini R, Chelo E, Branconi F, et al. Dynamic echohysteroscopy: A new diagnostic technique in the study of female infertility. Acta Eur Fertil. 1981;12:165-171.

13 Hill A. Sonohysterography in the office: Instruments and technique. Contemp Obstet Gynecol. 1997;42:95-101.

14 Andersen ES, Knudsen A, Rix P, Johansen B. Risk of malignancy index in the preoperative evaluation of patients with adnexal masses. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;90:109-112.

15 Guerriero S, Ajossa S, Garau N, et al. Ultrasonography and color Doppler-based triage for adnexal masses to provide the most appropriate surgical approach. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:401-406.

16 Lee EJ, Kwon HC, Joo HJ, et al. Diagnosis of ovarian torsion with color Doppler sonography: Depiction of twisted vascular pedicle. J Ultrasound Med. 1998;17:83-89.

17 Day Baird D, Dunson DB, Hill MC, et al. High cumulative incidence of uterine leiomyoma in black and white women: Ultrasound evidence. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;188:100-107.

18 Hassani SN, Bard RL, Dounel SN. Ultrasonic patterns of uterine fibroids. Diagn Gynecol Obstet. 1981;3:91-94.

19 Cicinelli E, Romano F, Anastasio PS, et al. Transabdominal sonohysterography, transvaginal sonography, and hysteroscopy in the evaluation of submucous myomas. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:42-47.

20 Bradley LD, Falcone T, Magen AB. Radiographic imaging techniques for the diagnosis of abnormal uterine bleeding. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2000;27:245-276.

21 Howard FM. The role of laparoscopy in the evaluation of chronic pelvic pain: Pitfalls with a negative laparoscopy. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1996;4:85-94.

22 Horrow MM. Ultrasound of pelvic inflammatory disease. Ultrasound Q. 2004;20:171-179.

23 Dueholm M, Forman A, Jensen ML, et al. Transvaginal sonography combined with saline contrast sonohysterography in evaluating the uterine cavity in premenopausal patients with abnormal uterine bleeding. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;18:54-61.

24 Tal J, Timor-Tritsch I, Degani S. Accurate diagnosis of postabortal placental remnant by sonohysterography and color Doppler sonographic studies. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1997;43:131-134.

25 Montegudo A, Carreno C, Timor-Tritsch IE. Saline infusion sonohysterography in nonpregnant women with previous cesarean delivery: The “niche” in the scar. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:1105-1115.

26 Bakos O, Lundkust O, Bergh T. Transvaginal sonographic evaluation of endometrial growth and texture in spontaneous ovary cycles—a descriptive study. Human Reprod. 1993;8:799-806.

27 Persadie RJ. Ultrasonographic assessment of endometrial thickness: A review. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2002;24:131-139.

28 O’Connell LP, Fries MH, Zeringue E, Brehm W. Triage of abnormal postmenopausal bleeding: A comparison of endometrial biopsy and transvaginal sonohysterography versus fractional curettage with hysteroscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178:956-961.

29 Rodriquez GC, Yaqub N, King ME. A comparison of the Pipelle device and the Vabra aspirator as measured by endometrial denudation in hysterectomy specimens: The Pipelle device samples significantly less of the endometrial surface than the Vabra aspirator. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:55-59.

30 Guido RS, Kanbor A, Ruhlin M, Christopherson WA. Pipelle endometrial sampling sensitivity in the detection of endometrial cancer. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:553-555.

31 Varner RE, Sparks JM, Cameron DC, et al. Transvaginal sonography of the endometrium in postmenopausal women. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;78:195-199.

32 Lin MC, Gosink BB, Wolf SL, et al. Endometrial thickness after menopause: Effect of hormone replacement. Radiology. 1991;180:427-432.

33 Currie JL. US monitoring of endometrial thickness in estrogen replacement therapy. Radiology. 1991;180:306.

34 Sheth S, Hamper UM, Kurman R. Thickened endometrium in the postmenopausal woman: Sonographic–pathologic correlation. Radiology. 1993;187:135-139.

35 Kupfer MC, Schiller VL, Hansen GC, et al. Transvaginal sonographic evaluation of endometrial polyps. J Ultrasound Med. 1994;13:535-539.

36 Hulka CA, Hall DA, McCarthy K, et al. Endometrial polyps, hyperplasia, and carcinoma in postmenopausal women: Differentiation with endovaginal sonography. Radiology. 1994;191:755-758.

37 Clevenger-Hoeft M, Syrop CH, Stovall DW, Van Voorhis BJ. Sonohysterography in premenopausal women with and without abnormal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:516-520.

38 Goldstein RB, Bree RL, Benson CB, et al. Evaluation of the woman with postmenopausal bleeding: The Society of Radiologists in Ultrasound-sponsored consensus conference statement. J Ultrasound Med. 2001;20:1025-1036.

39 Gupta JK, Chien PFW, Voit D, et al. Ultrasonographic endometrial thickness for diagnosing endometrial pathology in women with postmenopausal bleeding: A meta-analysis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2002;81:799-816.

40 Tabor A, Watt HC, Wald NJ. Endometrial thickness as a test for endometrial cancer in women with postmenopausal bleeding. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;99:663-670.

41 Lindheim SR, Kavic S, Sauer MV. Intraoperative applications of saline infusion ultrasonography. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1999;16:390-394.

42 Cohen JR, Luxman D, Sagi J, et al. Sonohysterography for distinguishing endometrial thickening from endometrial polyps in postmenopausal women. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1994;4:227-230.

43 Goldstein SR. Use of ultrasonohysterography for triage of perimenopausal patients with unexplained uterine bleeding. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:565-570.

44 Dubinsky TJ, Parvey HR, Gormaz G, et al. Transvaginal hysterosonography in the evaluation of small endoluminal masses. J Ultrasound Med. 1995;14:1.

45 Neele SJ, Marchien van Baal W, van der Mooren MJ, et al. Ultrasound assessment of the endometrium in healthy asymptomatic early post-menopausal women: Saline infusion sonohysterography versus transvaginal ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2000;16:254-259.

46 Dubinsky TJ, Parvey R, Gormaz G, et al. Transvaginal hysterosonography: Comparison with biopsy in the evaluation of postmenopausal bleeding. J Ultrasound Med. 1995;14:887-893.

47 Epstein E, Ramirez A, Skoog L, Valentin L. Transvaginal sonography, saline contrast and hysteroscopy for the investigation of women with postmenopausal bleeding and endometrium > 5mm. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2001;18:157-162.

48 Schwartz LB, Snyder J, Horan C, et al. The use of transvaginal ultrasound and saline infusion sonohysterography for the evaluation of asymptomatic postmenopausal breast cancer patients on tamoxifen. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1998;11:48-53.

49 Bissett D, Davis JA, George WD. Gynaecological monitoring during tamoxifen therapy. Lancet. 1994;344:1244.

50 Seoud M, Shamseddine A, Khalil A, et al. Tamoxifen and endometrial pathologies: A prospective study. Gynecol Oncol. 1999;75:15-19.

51 Achiron R, Lipitz S, Sivan E, et al. Changes mimicking endometrial neoplasia in postmenopausal, tamoxifen-treated women with breast cancer: A transvaginal Doppler study. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1995;6:116-120.

52 Bertelli G, Valenzano M, Costantini S, et al. Limited value of sonohysterography for endometrial screening in asymptomatic, postmenopausal patients treated with tamoxifen. Gynecol Oncol. 2000;78:275-277.

53 Bertelli G, Venturini M, Del Mastro L, et al. Tamoxifen and the endometrium: Findings of pelvic ultrasound examination and endometrial biopsy in asymptomatic breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1998;47:41-46.

54 Cecchini S, Ciatto S, Bonardi R, et al. Screening by ultrasonography for endometrial carcinoma in postmenopausal breast cancer patients under adjuvant tamoxifen. Gynecol Oncol. 1996;60:409-411.

55 Love CD, Muir BB, Scrimgeour JB, et al. Investigation of endometrial abnormalities in asymptomatic women treated with tamoxifen and an evaluation of the role of endometrial screening. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2050-2054.

56 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Tamoxifen and endometrial cancer. ACOG Committee Opinion 232. Washington, D.C.: ACOG, 2000.

57 Hann LE, Gretz EM, Bach AM, Francis SM. Sonohysterography for evaluation of the endometrium in women treated with tamoxifen. Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177:337-342.

58 Cohen MA, Sauer MV, Keltz M, Lindheim SR. Utilizing routine sonohysterography to detect intrauterine pathology before initiating hormone replacement therapy. Menopause. 1999;6:68-70.

59 Sit AS, Modugno F, Hill LM, et al. Transvaginal ultrasound measurement of endometrial thickness as a biomarker for estrogen exposure. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;12:1459-1465.

60 DeWaay DJ, Syrop CH, Nygaard IE, et al. Natural history of uterine polyps and leiomyomata. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:3-7.

61 Cohen MA, Seitzinger MR, Sauer MV, Lindheim SR. The value of sonohysterography in postmenopausal women prior to initiating hormone replacement therapy. NAMS (abstract). 1999.

62 Langer RD, Pierce JJ, O’Hanlan KA, et al. Transvaginal ultrasonography compared with endometrial biopsy for the detection of endometrial disease. NEJM. 1997;337:1792-1798.

63 Fleisher AC, Wheeler JE, Lindsay I, et al. An assessment of the value of ultrasonographic screening for endometrial disease in postmenopausal women without symptoms. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:70-75.

64 Mais V, Guerriero S, Ajossa S, et al. The efficiency of transvaginal ultrasonography in the diagnosis of endometrioma. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:776-780.

65 Goldstein SR, Monteagudo A, Popiolek D, et al. Evaluation of endometrial polyps. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:669-674.

66 Cowles TA, Magrina JF, Masterson BJ, et al. Comparison of clinical and surgical staging in patients with endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 1985;66:413-416.

67 Schink JC, Lurain JR, Wallemark CB, Chmiel JS. Tumor size in endometrial cancer: A prognostic factor for lymph node metastasis. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:216-219.

68 Valenzano M, Podesta M, Giannesi A, et al. The role of transvaginal ultrasound and sonohysterography in the diagnosis and staging of endometrial adenocarcinoma. Radiol Med. 2001;101:365-370.

69 Devore GR, Schwartz PE, Morris J. Hysterography: A 5-year follow-up in patients with endometrial carcinoma. Obstet Gynecol. 1982;60:369-372.

70 Alcazar JL, Errasti T, Zornoza A. Saline infusion sonohysterography in endometrial cancer: Assessment of malignant cells dissemination risk. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2000;79:321-322.

71 Shalev J, Meizner I, Bar-Hava I, et al. Predictive value of transvaginal sonography performed before routine diagnostic hysteroscopy for evaluation of infertility. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:412-417.

72 Kim AH, McKay H, Keltz MD, et al. Sonohysterographic screening before in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1998;69:841-844.

73 Pellerito JS, McCarthy SM, Doyle MB, et al. Diagnosis of uterine anomalies: Relative accuracy of MR imaging, endovaginal sonography, and hysterosalpingography. Radiology. 1992;183:795-800.

74 Soares SR, Barbosa dos Reis MM, Carnargos AF. Diagnostic accuracy of sonohysterography, transvaginal sonography, and hysterosalpingography in patients with uterine cavity diseases. Fertil Steril. 2000;73:406-411.

75 Sardanelli F, Renzetti P, Oddone M. Toma P: Uterus didelphys with blind hemivagina and ipsilateral renal agensis: MR findings before and after vaginal septum resection. Eur J Radiol. 1995;19:164-170.

76 Letterie GS, Haggerty M, Lindee G. A comparison of pelvic ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging as diagnostic studies for müllerian tract abnormalities. Int J Fertil Menopausal Stud. 1995;40:34-38.

77 Reuter KL, Daly DC, Cohen SM. Septate versus bicornuate uteri: Errors in imaging diagnosis. Radiology. 1989;172:749-752.

78 Yoder IC. Diagnosis of uterine anomalies: Relative accuracy of MR imaging, endovaginal sonography, and hysterosalpingography. Radiology. 1992;185:343.

79 Keltz MD, Olive DL, Kim AH, Arici A. Sonohysterography for screening in recurrent pregnancy loss. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:670-674.

80 Raga F, Bonilla-Musoles F, Blanes J, Osborne NG. Congenital müllerian anomalies: Diagnostic accuracy of three-dimensional ultrasound. Fertil Steril. 1996;65:523-528.

81 Campbell S, Bourne TH, Tan SL, Collins WP. Hysterosalpingo-contrast sonography (HyCoSy) and its future role within the investigation of infertility in Europe. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 1994;4:245-249.

82 Session DR, Lerner JP, Tchen CK, Kelly AC. Ultrasound-guided fallopian tube cannulation using Albunex. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:972-974.

83 Jeanty P, Besnard S, Arnold A, et al. Air-contrast sonohysterography as a first step assessment of tubal patency. J Ultrasound Med. 2000;19:519-527.

84 Spandorfer SD, Goldstein J, Navarro J, et al. Difficult embryo transfer has a negative impact on the outcome of in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:654-655.

85 Lindheim SR, Sauer MV. Upper genital-tract screening with hysterosonography in patients receiving donated oocytes. Intl J Gynecol Obstet. 1998;60:47-50.

86 Gonen Y, Casper FR, Jacobson W, Blankier J. Endometrial thickness and growth during ovarian stimulation: A possible predictor of implantation in in vitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1989;52:446-450.

87 Glissant A, de Mouzon J, Frydman R. Ultrasound study of the endometrium during in vitro fertilization cycles. Fertil Steril. 1985;44:786-790.

88 Fleisher AC, Herbert CM, Sacks JA, et al. Sonography of the endometrium during conception and nonconception cycles of in vitro fertilization cycles and embryo transfer. Fertil Steril. 1986;46:442-447.

89 Welker BG, Gembruch U, Diedrich K, et al. Transvaginal sonography of the endometrium during ovum pickup in stimulated cycles for in vitro fertilization cycles. J Ultrasound Med. 1989;8:549-553.

90 Dickey RP, Olar TT, Curole DN, et al. Endometrial pattern and thickness associated with pregnancy outcome after assisted reproduction technologies. Hum Reprod. 1992;7:418-421.

91 Krampl E, Feichtinger W. Endometrial thickness and patterns. Hum Reprod. 1993;8:1339.

92 Freidler S, Schenker JG, Herman A, Lewin A. The role of ultrasonography in the evaluation of endometrial receptivity following assisted reproductive treatment: A critical review. Hum Reprod Update. 1996;2:323-325.

93 Coroleu B, Carreras O, Veiga A, et al. Embryo transfer under ultrasound guidance improves pregnancy rates after in vitro fertilization. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:616-620.

94 Lindheim SR, Cohen M, Sauer MV. Operative ultrasonography for upper genital tract pathology. J Assist Reprod Genet. 1998;15:542-546.

95 Lindheim SR, Morales AJ. Operative ultrasound using an echogenic loop snare for intrauterine pathology. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2003;10:107-110.

96 Shalev E, Zuckerman H. Operative hysteroscopy under real-time ultrasonography. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;153:1360-1361.

97 Letterie GS, Kramer DJ. Intraoperative ultrasound guidance for intrauterine endoscopic surgery. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:654-656.

98 Shalev E, Shimonoi Y, Peleg D. Ultrasound controlled hysteroscopy. J Am Coll Surg. 1994;179:70-71.

99 Coccia ME, Becattini C, Bracco GI, et al. Pressure lavage under ultrasound guidance: A new approach for outpatient treatment of intrauterine adhesions. Fertil Steril. 2001;75:601-606.

100 Kieler H, Ahlsten G, Haglund B, et al. Routine ultrasound screening in pregnancy and the children’s subsequent neurologic development. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:750-756.

101 Bonnamy L, Marret H, Perrotin F, et al. Sonohysterography: A prospective survey of results and complications in 81 patients. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;102:42-47.

102 Yoshimitsu K, Nakamura G, Nakano H. Dating sonographic endometrial images in the normal ovulatory cycle. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1989;28:33-39.

103 Lindheim SR, Morales AJ. Comparisons of sonohysterography to hysteroscopy: Lessons learned and avoiding pitfalls. J Am Assn Gynecol Laparosc. 2002;9:223-231.

104 Adams J, Polson DW, Franks S. Prevalence of polycystic ovaries in women with anovulation and idiopathic hirsutism. BMJ. 1986;293:355-359.

105 Hansen KR, Morris JL, Thyer AC, Soules MR. Reproductive aging and variability in the ovarian antral follicle count: Application in the clinical setting. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:577-583.

106 Dessole S, Farina M, Capobianco G, et al. Determining the best catheter for sonohysterography. Fertil Steril. 2001;76:605-609.

107 Keltz MD, Arici A, Duleba A, Olive DL. A technique for sonohysterographic evaluation of the endometrial cavity and tubal patency. J Gynecol Tech. 1995;1:213-216.

108 Lindheim SR. Echosight Jansen-Anderson Coaxial catheter guided hysteroscopy. J Am Assn Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8:307-311.

109 Hackeloer B, Fleming R, Robinson H, et al. Correlation of ultrasonic and endocrinologic assessment of human follicular development. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1979;135:122-128.

110 Hall DA, Hann LE, Ferrucci JT, et al. Sonographic morphology of the normal menstrual cycle. Radiology. 1979;133:185-188.

111 Fleicher AC, Kalemaris GC, Entman SS. Sonographic depiction of the endometrium during normal cycles. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1986;12:271-275.

112 Sakamoto C. Sonographic criteria of phasic changes in human endometrial tissue. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1985;23:7-12.

113 Abramowicz JS, Archer DF. Uterine endometrial peristalsis—a transvaginal ultrasound study. Fertil Steril. 1990;54:451-454.

114 Kunz G, Beil D, Dioniger H, et al. The uterine peristaltic pump: Normal and impeded sperm transport within the female genital tract. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;424:267-277.

115 Leyendecker G, Kunz G, Wilde L, et al. Uterine hyperperistalsis and dysperistalsis as dysfunctions of the mechanism of rapid sperm transport in patients with endometriosis and infertility. Hum Reprod. 1996;11:1542-1551.

116 Farquhar CM, Rae T, Thomas DC, et al. Doppler ultrasound in the nonpregnant pelvis. J Ultrasound Med. 1989;8:451-457.

117 Timor-Tritsch IE, Rottem S. Transvaginal ultrasonographic study of the fallopian tube. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:424-428.

118 Khalife S, Falcone T, Hemmings R, Cohen D. Diagnostic accuracy of transvaginal ultrasound in detecting free pelvic fluid. J Reprod Med. 1998;43:795-798.

119 Bailey CL, Ueland FR, Land GL, et al. The malignant potential of small cystic tumors in women over 50 years of age. Gynecol Oncol. 1998;69:3-7.

120 Sladkevicius P, Valentin L, Marsal K. Transvaginal Doppler examination of uteri with myomas. J Clin Ultrasound. 1996;24:135-140.

121 Reinhold C, McCarthy S, Brte PM, et al. Diffuse adenomyosis: Comparison of endovaginal ultrasound and MR imaging with histopathologic correlation. Radiology. 1996;199:151-158.

122 Collins JI, Woodward PJ. Radiological evaluation of infertility. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 1995;16:304-316.

123 Cullinan JA, Fleischer AC, Kepple DM, Arnold AL. Sonohysterography: A technique for endometrial evaluation. Radiographics. 1995;15:501-514.

124 Fedele L, Bianchi S, Dorta M, Vignali M. Intrauterine adhesions: Detection with transvaginal ultrasound. Radiology. 1996;199:757-759.

125 Volpi E, DeGrandis T, Zuccaro G, et al. Role of transvaginal sonography in the detection of endometriomata. J Clin Ultrasound. 1995;23:163-165.

126 Kupfer MC, Schwimmer SR, Lebovic J. Transvaginal sonographic appearance of endometriomata: Spectrum of findings. J Ultrasound Med. 1992;11:129-132.

127 Dogan MM, Ugar M, Soysal SK, et al. Transvaginal sonographic diagnosis of ovarian endometrioma. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1996;52:145-147.

128 Moore KL. Formation of the bilaminar embryo: The second week. In Moore KL, editor: The Developing Human: Clinically Oriented Embryology, 4th ed., Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1988.

129 Sauerbrei E, Cooperberg PL, Poland JB. Ultrasound demonstration of the normal fetal yolk sac. J Clin Ultrasound. 1980;8:217-219.

130 Fine C, Cortier M, Doubilet P. Fetal heart rates: Values throughout gestation. J Ultrasound Med. 1988;7:S105.

131 Kadar N, DeVore G, Romero R. Discriminatory hCG zone. Its use in sonographic evaluation for ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1981;58:156-161.

132 Barnhart KT, Katz I, Hummel A, Gracia CR. Presumed diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100:505-510.

133 Timor-Tritsch IE, Yeh MN, Peisner DB, et al. The use of transvaginal ultrasound in the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;161:157-161.

134 Goldstein SR, Snyder JR, Watson C, Danon M. Very early pregnancy detection with endovaginal ultrasound. Obstet Gynecol. 1988;72:200-204.

135 Barnhart KT, Kamelle SA, Simhan H. Diagnostic accuracy of ultrasound, above and below the β-hCG discriminatory zone. Obstet Gynecol. 1999;94:583-587.

136 Tal J, Haddad S, Gordon N, Timor-Tritsch IE. Heterotopic pregnancy after ovulation induction and assisted reproductive technologies: A literature review from 1971 to 1993. Fertil Steril. 2006;66:1-12.

137 Turetsky DB, Alexander AA, Linden SS. Pseudogestational sac of ectopic pregnancy simulating intrauterine pregnancy with transvaginal sonography. J Clin Ultrasound. 1991;141:840-842.

138 Nyberg DA, Mack LA, Laing FC, Patten RM. Distinguishing normal from abnormal gestational sac growth in early pregnancy. J Ultrasound Med. 1988;6:23-27.

139 Schatz R, Jansen CAM, Wladimiroff JW. Embryonic heart activity: Appearance and development in early human pregnancy. BJOG. 1990;97:989-994.

140 Rempen A. Diagnosis of early pregnancy with vaginal sonography. J Ultrasound Med. 1990;9:711-716.

141 Lau S, Tulandi T. Conservative medical and surgical management of interstitial ectopic pregnancy. Fertil Steril. 1999;72:207-215.