Chapter 41 Surgical Management of Lesions of the Clivus

Different pathologic lesions can develop in this region.1 Histologically, clival lesions can be benign (e.g., meningiomas, epidermoid cyst, cholesterol granuloma, or glomus jugulare tumors with major petroclival involvement), of low-grade malignancy (e.g., chordomas and chondrosarcomas), or of high-grade malignancy (e.g., squamous cell cancer, adenocarcinoma, basal cell carcinoma, osteogenic sarcoma, or metastases). Some of these tumors have an intradural location, whereas others are extradural.

The lesions that most often involve this region are meningiomas (commonly intradural), followed (much less commonly) by chordomas, which are often extradural. The former grow from the dura that covers the clivus or the passage from the clivus and the petrous bone (petroclivus fold),2 whereas the latter originate directly from embryonic residues enclosed in the bone of the clivus.3–6

Tumors in the region of the clivus are difficult to treat using conventional neurosurgical approaches. Until a few decades ago, because of the relative inaccessibility of the clivus and its proximity to the brain stem and surrounding neurovascular structures, the results of surgical treatment were so dismal that these tumors were often considered incurable.1

Advances in microsurgery of the skull base have resulted in the development and refinement of approaches to petroclival and clival lesions,7–57 better methods for tumor removal, and innovative techniques44,45,58–62 to minimize injury to neural and vascular structures during tumor removal. These factors enable the surgeon to treat these tumors more effectively, aiming at a radical excision with an acceptable morbidity and mortality.

In some cases, the combined effort of the neurosurgeon with those in other disciplines interested in skull base surgery (e.g., otolaryngology or maxillofacial surgery) constitutes real progress in the realization of special approaches that aim at improving the exposure of the tumor and reducing trauma to the brain during surgery. Endoscopic skull base surgery is the most recent result of this multidisciplinary concept.63

In recent years, the introduction of the endoscope in trans-sphenoidal surgery and the use of extended endoscopic approaches have allowed resection of chordomas involving the lower clivus, and even the odontoid, with good short-term results and low surgical morbidity.64–72

Surgical Anatomy

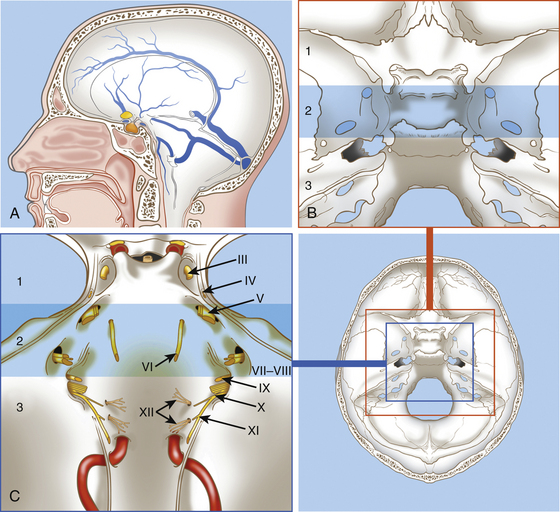

The clivus is located at the midline, in the deepest part of the skull base. It constitutes the inclined anteroinferior surface of the posterior cranial fossa and extends from the dorsum sellae to the foramen magnum (Fig. 41-1). It is formed by a sphenoidal part (corresponding to the superior third) that extends from the dorsum sellae to the spheno-occipital synchondrosis and by an occipital part (corresponding to the inferior two thirds) that reaches the anterior intraoccipital synchondroses.3,73

The clivus is usually divided into the upper, middle, and lower clivus25 (see Fig. 41-1) or into superior and inferior halves of the clivus.74

The topographic anatomy of the clivus makes several surgical approaches feasible.1,11,34,35,37,41,75,76 The choice of an approach to remove a tumor from this region must take into account the nature and location of the lesion (i.e., whether the lesion is intradural or extradural, its position in respect to the clivus, and its lateral extension).

The surgical approaches to the clivus are divided into three general groups: (1) anterior, (2) anterolateral, and (3) posterolateral. Anterior approaches are mainly used for extradural lesions that primarily involve the clivus and extend extracranially (e.g., chordoma and chondrosarcoma). For these tumors, the anterior approaches are usually extradural and include the trans-sphenoidal, transethmoidal, transoral–transpalatal, transmaxillary, and transcervical. A subfrontal transbasal extraintradural anterior approach can also be indicated for huge tumors with maximal involvement of the clival area and surrounding structures (e.g., chordoma, pituitary tumors, and craniopharyngiomas).

Extradural Lesions: Chordomas

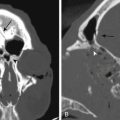

Chordomas are the most common extradural tumors of the clivus; they arise from remnants of the embryonic notochord and are located in all areas where the notochord existed (i.e., the entire clivus, sella turcica, foramen magnum, C1, and nasopharynx).3,5 From there, they may spread to the upper cervical region, petrous bone, posterior fossa, cavernous sinus, middle fossa, nasopharynx, and sphenoid sinus.3,5 Chordomas grow slowly but may present the characteristics of a malignant tumor in that they are locally aggressive with a tendency for regrowth.77 About 20% of chordomas recur as early as 1 year after surgery despite extensive surgical resection.48,78 Ten percent of chordomas show histologic signs of malignancy.5 Although it is considered difficult to identify histologic features indicative of aggressiveness,79,80 recent studies indicate that some molecular features of these tumors are associated with an aggressive biologic behavior.47,48,78,81,82 Metastases are relatively rare.78,80

Chordomas infiltrate the bone and spread into the epidural space, seeding the dura with microscopic deposits well beyond the limits of the tumor bulk.5,83 For this reason, they may invade the dura and become adherent to the arachnoid and pia mater. The tumor is often gelatinous and soft, with a jelly-like consistency, but it may also appear as a firm cartilaginous mass.

Chordomas are usually classified according to the portion of clivus involved by the tumor and by the extension to surrounding structures (e.g., upper clivus, middle clivus, lower clivus, and craniocervical junction tumors, with or without invasion of sphenoid, cavernous sinus, and petrous bone).1,3

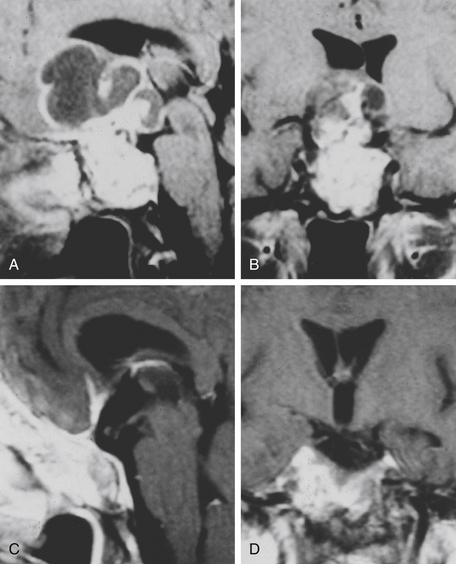

Computed tomography (CT) scan and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are the most important radiologic tools for diagnosis. The CT scan reveals the destruction of bone, whereas MRI shows the extension of the tumor, which appears nonhomogenously hyperintense on T2-weighted images and with a variable contrast enhancement after gadolinium.4

The most commonly involved cranial nerve is the sixth, and diplopia is the most common presenting symptom, particularly in the midclivus chordomas. Other symptoms include headache, pituitary dysfunction, visual field defects, cerebellar syndrome, torticollis, and brain stem syndrome.84

Surgical Treatment

Its deep position (at the central base of the skull) and its tendency to infiltrate the bone make total removal of the clivus chordoma difficult. Total resection leads to a significant improvement in survival at 5 years, with 90% and 52% with complete and partial resection, respectively;85 at 10 years, the recurrence-free survival rate in a large series for primarily operated patients (with a complete resection of 83%) was 42%; for reoperation cases (complete resection achieved in 30% of patients), it was 26%.86

In recent years, because of the development of innovative and complex approaches to the clival area29,30,34,35,37,41,42,67,68,86–91 and the extensive application of standard procedures to this area,12,13,16,36,38,84,92–100 many possibilities are at the disposal of the surgeon attempting radical removal of these tumors.

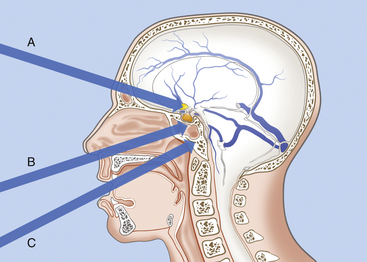

Because chordomas are basically extradural and midline tumors, they displace the neuraxis dorsally or dorsolaterally. Anterior midline extradural approaches are generally preferred (Fig. 41-2).20,46,52,83,92,101–105 These approaches allow a midline exposure of the clivus and a short working distance, avoiding any retraction of the brain.

The choice of surgical approach depends on the location and extension of the tumor. Even when only anterior extracranial approaches are considered, many options exist. These include the transbasal,13 extended subfrontal,104 microscopic trans-septal trans-sphenoidal,16,84,93–94 modified microsurgical endoscope-assisted sublabial or endonasal trans-sphenoidal,98,99 endoscopic endonasal trans-sphenoidal,64,67–71 trans-sphenoethmoidal,92 transmaxillary transnasal,106 transfacial,107 facial translocation,108 transmaxillary,109–110 midfacial degloving,103 transoral,12 mandible-splitting transoral,94 transcervical transclival,111 and anterior cervical112 approaches; Le Fort I osteotomy;113 unilateral Le Fort I osteotomy;114 total rhinotomy; and pedicled rhinotomy.115

All of these approaches are devoted to removing all clival lesions localized on the midline without important lateral extent. In the case of massive lateral extension, in which a midline approach is insufficient for the removal of the entire tumor, complex lateral approaches can be utilized as a primary or secondary procedure.1,5 These include, for lesions of the upper clivus, the subtemporal, transcavernous, and transpetrous apex approaches; for lesions of the midclivus, subtemporal and infratemporal approaches; and for lesions of the lower clivus with lateral extension to the occipital condyle, jugular foramen, and cervical area, the extreme lateral transcondylar (“far lateral”) approach.26,43,86,116

• For chordomas located in the upper and middle clivus, the trans-sphenoidal approach is favored.

• For lesions of the lower clivus that involve the foramen magnum, C1, and C2, the transoral approach is preferred, with or without splitting of the palate.

• For tumors in the lower clivus, foramen magnum, and first cervical spinal bodies, with important lateral extension, the Le Fort I osteotomy can be used with a midline incision of the hard and soft palate and lateral swinging of the two flaps of the hard palate.

• For huge tumors involving the entire clival area, the sphenoid, and the sellar region and extending anteriorly to the optic nerves, the transbasal or extended subfrontal route is utilized.

• For lesions that involve the lower clivus and the upper cervical region and that extend laterally into the occipital condyle and the jugular bulb on one side, the extreme lateral approach with partial condylectomy seems particularly well suited.

Other anterior approaches can be utilized, including the following:

• The trans-sphenoethmoidal approach92 provides access to the entire sphenoid sinus, prepontine space, and superior clivus; a limited medial maxillectomy improves access to the inferior clivus.

• The transfacial approach107 is indicated for extradural tumors confined on the midline and extending from the level of the sellar floor to the foramen magnum. This approach offers direct access to the clivus along its rostrocaudal extent up to the anterior arch of C1; with depression of the palate, the odontoid can also be visualized. The main advantage is to add, by this single facial route, the possibilities of the trans-sphenoidal and transoral routes, avoiding any injury to the hard and soft palate. The disadvantages are a facial scar and osteotomy of the facial skeleton.

• The recent application of the endoscope to trans-sphenoidal surgery, in either endoscope-assisted or pure endoscopic approaches, provides wider visualization of lesions extending from the upper clivus to the odontoid process; in the future, they will probably be substituted for most transfacial routes, even for tumors extending inferiorly to the odontoid and laterally to the petrous apex.64–72117

Trans-sphenoidal Approach

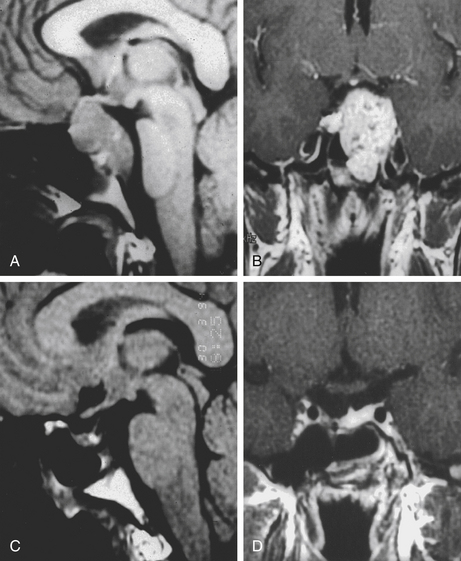

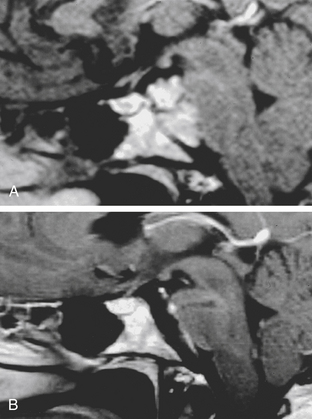

The trans-sphenoidal approach provides excellent exposure to chordomas of the sphenoid sinus, sella turcica, and upper and middle clivus (see Fig. 41-2), minimizing the morbidity of more complex surgical approaches13,16,84,96 with a route that, where necessary, can easily be repeated. The technique utilized for the sublabial trans-septal trans-sphenoidal procedure has already been described.118 Extensive experience obtained with pituitary tumors119–120 and with craniopharyngiomas121 has made this route safe and effective, even for other pathologies (Figs. 41-3 to 41-6). Several papers have reported that gross total tumor removal can be achieved in up to 70% of cases using the trans-sphenoidal approach, with excellent long-term survival and no evidence of disease at a mean of 38.6 months after surgery.84,94,95,98,99

The main disadvantages of this approach are represented by the limited lateral exposure and the deep and narrow field. Nevertheless, the correct use of long and angled curettes can allow a skillful surgeon to remove even large tumors (greater than 4 cm) that are not strictly confined to the midline.78 Application of endoscopy to the trans-sphenoidal route may increase the surgical field and allow even extensive tumors to be removed.45,64,67–71

When the tumor is found to be located intradurally, an opening of the dura mater can be realized to remove the intradural tumor. Afterward, an accurate reconstruction must be realized. We usually use a dural patch and fibrin glue. When a major intraoperative CSF leak (grade 3122) is evident, a lumbar drain is kept in place for 48 to 72 hours postoperatively.

Transoral Approach

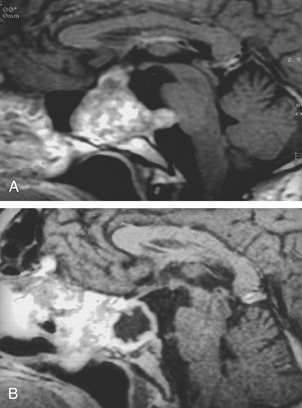

The transoral route is indicated for extradural lesions of the inferior clivus that are confined to the midline, protrude into the posterior pharyngeal region, and extend to C1 to C2 (see Fig. 41-2). The approach provides good exposure with limited surgical trauma.75,123 This route has been used for many years for epidural tumors of the cervical spine.124 Several reports have described the utilization of this surgical route to treat clivus chordomas.125–127

A modified transoral version has been described for chordomas.110,113 It combines the Le Fort I osteotomy with a midline incision of the hard and soft palate and allows lateral swinging of the two flaps of the hard palate based on their own palatine artery and nerves. The advantage is extensive exposure of the region, inferiorly and laterally (Fig. 41-7); the wound must be closed carefully to preserve occlusion and functioning of the palate. A unilateral Le Fort I osteotomy can be realized for laterally growing tumors.114 Neuronavigation in transoral approach has been found to be a useful tool for planning and checking the limits of resection and for reducing morbidity in chordoma surgery.44

The Endoscope: A Surgical Adjunct for Wider Vision and Exposure

As a result of technological progress and collaboration between neurosurgeons and otolaryngologists,63 the endoscope has been applied to trans-sphenoidal and transoral surgery to get visualization in these deep surgical corridors that is wider than the microsurgical vision. The use of the endoscopes in microsurgical approaches has allowed a view behind the corner achieved by angled (30 and 45 degrees) scopes.98,99 The main limit of endoscope-assisted microsurgery remains though the narrow surgical corridor in which the endoscope is positioned; this reduces the endoscope to a complex mirror to visualize tumor remnants, as tumor removal under an endoscopic view may be not possible because of the space limitation created by the self-retractor.

In recent years, “pure” endoscopic trans-sphenoidal approaches have been developed63 that use only the endoscope as a visualization tool. The approaches are performed through both nostrils to allow for a bimanual technique and a wide range of free motion. The major limit of pure endoscopic skull base surgery is the loss of the binocular vision provided by the microscopic technique. When the wider visualization achieved by the endoscope is coupled with wider exposure, the full advantage of the endoscopic technique is achieved, extending the realm of trans-sphenoidal surgery to the cavernous sinus,128 petrous apex,117 lower clivus, and odontoid process.65,72

Results of the endoscopic series in the treatment of clival chordomas are at least comparable to the microsurgical trans-sphenoidal series,64,67,68,71 though the small number of patients and the short follow-up preclude definitive conclusions in terms of survival and recurrence rate.

The endoscope has also been applied to the transoral approach to the anterior craniovertebral junction in limited series.129 A pure endonasal endoscopic approach to C1 and the odontoid process has also been described.72,130 The main advantage of this approach, as compared to the transoral, is the visualization of the whole clivus and the avoidance of the soft palate splitting; its major limitation is the lowest extension of the surgical field, which is usually 9 mm above the base of the C2 body. The application of the endoscope to the transoral approach may reduce the need for splitting the soft palate yet maintain a satisfactory surgical maneuverability.131

Subfrontal Transbasal or Extended Frontal Approach

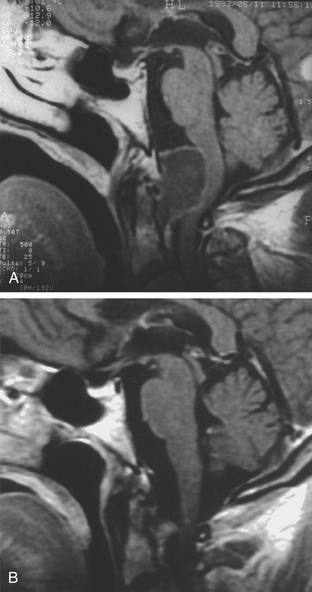

The subfrontal transbasal or extended frontal route can be utilized for chordomas with both intradural and extradural extension and with extensive involvement of the clivus and surrounding structures.5 The approach is a modification of the “transbasal approach” of Derome.13,132,133 After a bifrontal craniotomy (including the orbital roof and nasal bones), the anterior skull base is exposed extradurally on both sides (Fig. 41-8; see also Fig. 41-2). The planum sphenoidale and part of the anterior wall of the sella are removed. The clivus is reached anterior to the sella and exposed up to the rim of the foramen magnum (see Fig. 41-2). If the lesion presents an intradural extension, the frontal dura is opened. It also allows for the removal of tumors that extend near to the clivus (i.e., the frontal suprasellar region, orbits, paranasal sinuses, and temporal fossa). This approach has been used for different tumors such as craniopharyngiomas (Fig. 41-9), meningiomas, or pituitary tumors.

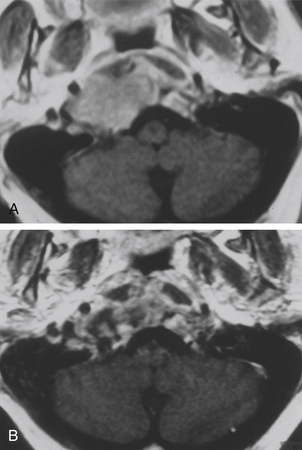

Extreme Lateral Transcondylar Approach

The extreme lateral transcondylar approach is useful for the management of both intradural and extradural lesions that involve the lower clival and foramen magnum regions (Figs. 41-10 and 41-11), with extension into the occipital condyles, jugular bulb, and upper cervical spine.15,26,134,135 The technical steps of the approach have been described by many authors.8,26,43,76,118,133 The main advantage of this route is the direct view that it offers to the ventral aspect of the foramen magnum without requiring brain stem retraction.

Postoperative Adjunctive Radiotherapy

Although the definitive modality for treating clival chordomas is surgical resection, an adjunctive treatment can be considered in selected cases. A correlation between radiation dose and length of the disease-free interval has been indicated;136 however, some authors remain somewhat skeptical as to the actual efficacy of postoperative radiotherapy in the management of chordomas.86,137–139 Conventional external beam radiotherapy, after partial or subtotal removal, does not seem to affect the regrowth of the tumor.140 Nevertheless, a better prognosis for small remnants is achieved with proton beam therapy.141 Although used in small series, stereotactic radiosurgery, carbon ion radiotherapy, and radiofrequency ablation appear promising options for adjunctive treatment of chordoma tumors.142–149

Intradural Lesions: Meningiomas

Meningiomas of the clivus and apical petrous bone are the most common intradural neoplasms of this region. Their natural history is characterized by a slow but progressive growth that eventually leads these tumors to achieve an enormous size before manifesting neurologic symptoms related to distortion of the brain stem or cranial nerves III to XII. The growth pattern of these tumors may be unpredictable, and the major factors that influence their growth remain unknown.150

According to Yasargil et al.,2 these meningiomas may be attached “at any of the lateral sites along the petroclival borderline, where the sphenoidal, petrous and clival bones meet.” These authors suggested that such basal tumors can be divided into clival, petroclival, and sphenopetroclival, according to their points of insertion and extent.

Clival meningiomas originate from the clival dura. They are rare and commonly encase the basilar artery and its branches. Petroclival meningiomas are tumors that originate in the upper two thirds of the clivus at the petroclival junction, medial to the entry of the trigeminal root in Meckel’s cave.2,151,152 These meningiomas often displace the basilar artery and the brain stem on the opposite side; however, in up to 25% of patients, there is encasement of the artery.153 Sphenopetroclival meningiomas are the most extensive of these lesions, involving the clivus and the petrous apex. These meningiomas invade the posterior cavernous sinus and the sphenoid sinus and grow into the middle and posterior fossae.152

The classification of meningiomas of this area can also be based on the anatomic location of the tumor with reference to the clivus (i.e., upper, middle, or lower) and to the size and volume of the tumor (i.e., medium, up to 2.5 cm in average diameter; large, 2.5 to 4.5 cm; and giant, more than 4.5 cm).154

Surgical Treatment

For safe excision of these deep tumors, an adequate exposure (with a low or basal approach to limit or avoid brain retraction) is necessary. The combined supratentorial and infratentorial approach, which Malis20 called the petrosal approach,9,155 was the first progress in the surgical exposure of the petroclival region. Thereafter, several surgical approaches were suggested to reach tumors in this region.12,66,156–158 In these, the petrous part of the temporal bone is often removed to reduce retraction of the temporal lobe and cerebellum and to provide better exposure of the clivus and ventral surface of the brain stem.

Surgical removal of the petrous bone was first used by King in 1970.159 A limited anterior resection (anterior transpetrosal approach), with preservation of hearing, was reported by Kawase et al. in 1985.160 Since then, the transpetrosal approach has received many modifications and has become a relevant part of the surgical approaches to the clivus and brain stem.∗ As suggested by Miller et al.,165 transpetrosal approaches can be divided basically into two types: (1) anterior petrosectomy, for lesions of the petrous apex and superior half of the clivus, and (2) posterior petrosectomy, for lesions of the petroclival area and cerebellopontine angle.

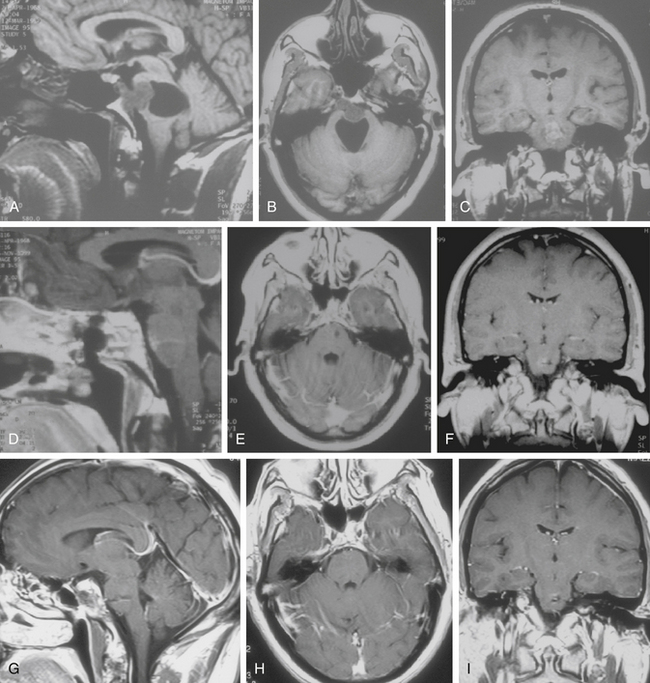

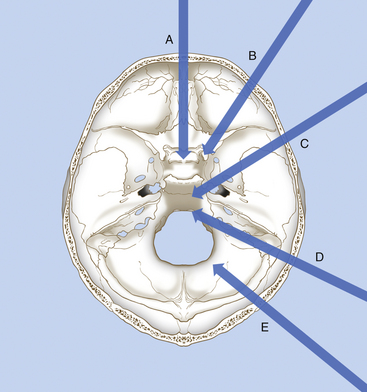

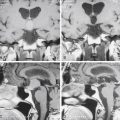

Meningiomas of the petroclival region can be reached through several routes that pass through the middle or posterior fossa (Fig. 41-12 and Table 41-1):

• Anterolateral route: frontotemporal trans-sylvian approach (usually combined with an orbitozygomatic osteotomy) for tumors of the upper clivus and tentorial notch

• Lateral route: anterior subtemporal approach with zygomatic osteotomy and anterior petrosectomy, for tumors of the petrous apex and upper half of the clivus (Fig. 41-13)

TABLE 41-1 Choice of Surgical Approach in Relation to the Location of the Tumor

| Location of Lesion (Sagittal Axis) | Surgical Approach | Location of Lesion (Coronal Axis) |

|---|---|---|

| Upper clivus | 1. Frontotemporal approach with orbitozygomatic osteotomy | Lateral to Dorello’s canal |

| 2. Subtemporal approach with a zygomatic osteotomy and an anterior petrosectomy | ||

| 3. Trans-sphenoidal approach∗ | Medial to III-VI CNs | |

| Upper and middle third of the clivus | 1. Subtemporal craniotomy with an anterior petrosectomy | Anterior to V3 |

| 2. Subtemporal–suboccipital craniotomy with a posterior petrosectomy | Posterior to V3 | |

| 3. Trans-sphenoidal approach∗ | Medial to V-VI CNs | |

| Lower third of the clivus | 1. Extreme lateral transcondylar approach | |

| 2. Trans-sphenoidal approach∗ | Medial to XII CN, no vascular involvement | |

| Middle and lower third of the clivus | 1. Combined posterior petrosectomy with an extreme lateral approach | |

| 2. Trans-sphenoidal approach∗ | Medial to XII CN, no vascular involvement | |

| Entire clivus through the level of the foramen magnum | Far lateral–combined supratentorial and infratentorial approach (including posterior petrosectomy or total petrosectomy) |

CN, cranial nerve.

Frontotemporal Trans-sylvian Approach

The frontotemporal trans-sylvian approach provides enough exposure for the removal of small tumors in the upper clivus and tentorial notch. If necessary, the floor of the middle fossa can also be exposed by performing a zygomatic or orbitozygomatic osteotomy with inferior displacement of the temporalis muscle.17,166,167

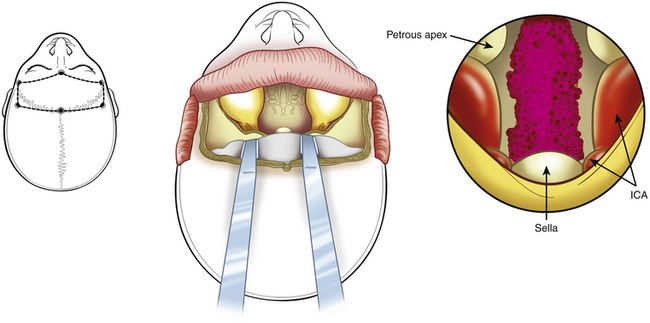

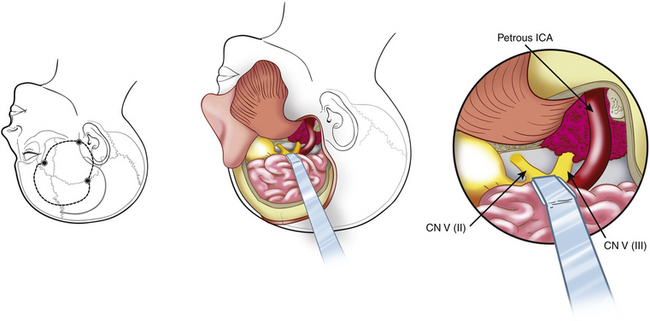

Anterior Subtemporal Approach with Anterior Petrosectomy

The anterior subtemporal approach with anterior petrosectomy is indicated for lesions of the tip of the petrous bone or for those involving the middle upper clival area that do not extend behind and below the internal auditory canal.19 This approach is also indicated when the greater part of the tumor is in the middle fossa, involving the cavernous sinus.25,41,154

An anterior temporal craniotomy is performed, followed by an orbitozygomatic osteotomy to extend the exposure of the conventional craniotomy anteriorly or inferiorly. The superior orbital fissure and the foramen ovale are exposed. To increase exposure at the petrous apex and midclivus, part of the petrous bone is removed. Kawase et al.19 described a triangle in the petrous bone (lateral to the trigeminal nerve and medial to the internal auditory meatus) that can be drilled, thus providing a route toward the lesions located in the region of the midclivus (see Fig. 41-12). Anteroinferior to this area is the horizontal segment of the petrous carotid artery. The petrous apex can be drilled at the Glasscock triangle (demarcated laterally by a line from the foramen spinosum toward the arcuate eminence ending at the facial hiatus, medially by the greater petrosal nerve, and at the base by the third trigeminal nerve division).165 The exposure can be further increased by anterior displacement of the carotid artery or by drilling the region of the cochlea and thus sacrificing hearing. During this procedure, care should be taken not to damage the abducens nerve that runs through Dorello’s canal just medial to this area.

The approach to the clivus can be obtained by simple fenestration of the petrous bone and attached tentorium19 or with an intradural transtentorial approach.74,163 In the latter case, intradural and extradural subtemporal approaches are combined with division of the tentorium and with intradural removal of the petrous bone from its apex to the cochlea.

Taniguchi and Perneczky164 suggested the application of the keyhole concept during surgery of petroclival lesions; this involves reduction of the conventional approach to its essential parts. The concept of restricting petrous bone removal to obtain the exposure necessary in individual cases has also been applied by several neurosurgeons.29,34,42,56,62

Subtemporo–Suboccipital Presigmoid Approach with Posterior Petrosectomy

In 1992, Spetzler et al.27 summarized neurosurgical approaches that required a posterior petrosectomy into three groups:

Approach That Preserves Hearing

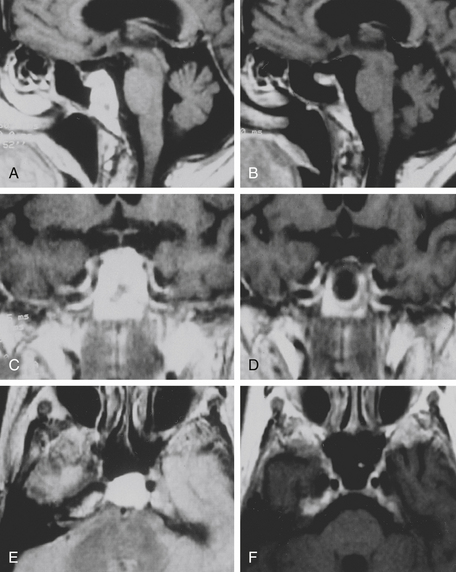

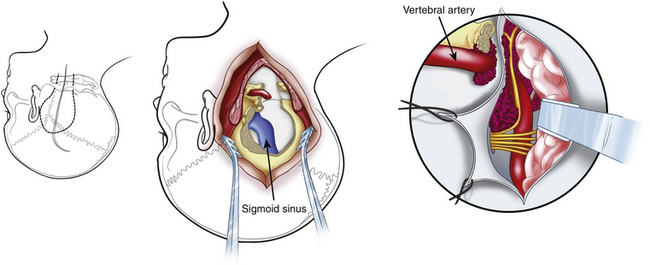

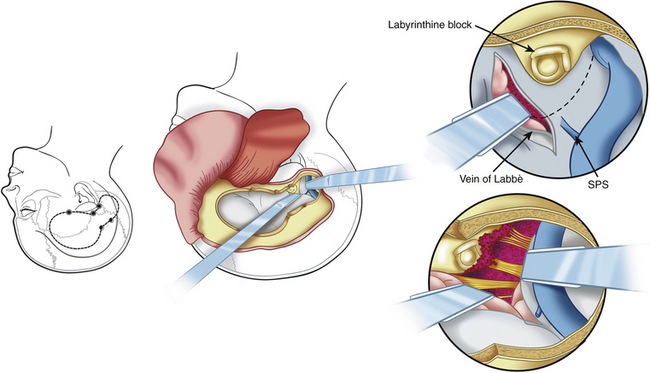

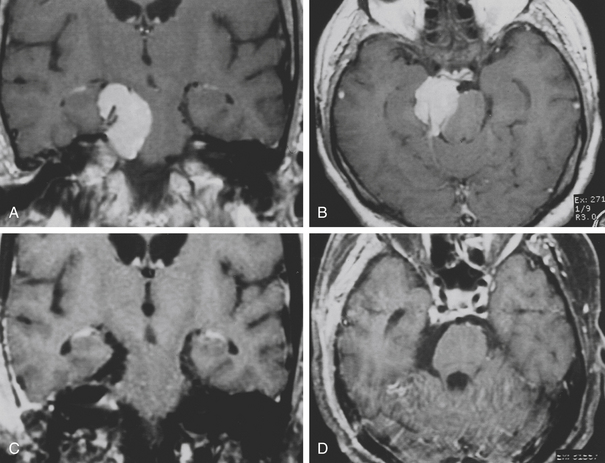

The presigmoid retrolabyrinthine transmastoid approach is most suitable for tumors of the clivus with extension in the middle and posterior fossa. This approach provides excellent exposure of the region ventral to the midbrain and pons. Described by Hakuba et al.168 in 1977 and refined by Al-Mefty and associates,7,30 this approach requires a low posterior temporal craniotomy and a lateral retrosigmoid craniotomy.161 A mastoidectomy is performed to expose the sigmoid sinus, the dura mater of the posterior cranial fossa situated anteriorly to the sinus, and the labyrinth. The sinus must be unroofed along its entire course to provide adequate length for mobilization, and the labyrinthine complex must be skeletonized completely from the mastoid cells to gain as much space as possible (Fig. 41-14). A labyrinthectomy improves access to the posterior fossa minimally: its use should be avoided unless hearing has been irreversibly lost. Some authors have suggested the use of a partial labyrinthectomy to widen exposure from the presigmoid route without affecting hearing.34,169

The dura mater of the posterior cranial fossa is incised anteriorly to the sigmoid sinus, and this incision is joined to that of the dura mater of the middle cranial fossa, thus preserving the sigmoid sinus, as described by Al-Mefty.161 The superior petrosal sinus is then resected, and the tentorium is incised (see Fig. 41-14). The fourth nerve is identified by moving the edge of the tentorium. A crucial step in the petrosal approach is the identification and preservation of the venous drainage of the posterior temporal lobe (i.e., the vein of Labbé and other basal veins). The transverse sinus may be divided to obtain improved exposure of structures below the auditory canal; this can be performed for patients who have good patency of the contralateral venous sinuses.

The advantages of this approach include minimal cerebellar and temporal lobe retraction and shortening of the operative distance to the tumor by 3 cm, when compared with the retrosigmoid approach. The surgeon has surgical access more anteriorly and closer to the clivus, which is important for the removal of lesions with a central location anterior to the brain stem (Figs. 41-15 and 41-16). Disadvantages are temporal lobe retraction and the possibility of injury to the vein of Labbé. Furthermore, paralysis of the lower cranial nerves constitutes one of the major sources of morbidity. Exposure of the lower clivus is limited by the jugular bulb, especially when it is high.

Access to the foramen magnum and inferior clivus can be improved by adding a retrosigmoid dural opening with anterolateral retraction of the sinus. If the lesion extends forward, the surgeon has to consider combining this approach with an anterior subtemporal zygomatic approach. Variants include the partial labyrinthectomy petrous apicectomy approach,41,56 extended lateral subtemporal approach,38 and anterior subtemporal medial transpetrosal approach.42

Approaches Involving Sacrifice of Hearing

The presigmoid translabyrinthine approach is an anterior extension of the presigmoid retrolabyrinthine approach. The approach involves the removal of the semicircular canals, thus enhancing the exposure. The transcochlear approach involves the anterior extension of the translabyrinthine approach.32,170

A combination of the transcochlear approach with extensive bone removal and anterior mobilization of the petrous internal carotid artery (ICA) is called a total petrosectomy approach.76

Approaches Involving Mobilization of the Facial Nerve

Various elaborate transpetrous approaches have been described, some of which involve mobilization of the facial nerve. A total petrosectomy approach has been described by Sekhar et al.154,163 The approach requires unroofing of the entire facial nerve and its posterior mobilization and anterior displacement of the petrous carotid artery.

Retrosigmoid Approach

A retrosigmoid approach is generally indicated for lateral, small, and medium-sized tumors of the midclivus. The approach is easy, but it requires the surgeon to work between the cranial nerves and the blood vessels in the cerebellopontine angle and does not provide adequate exposure of more medial or contralateral extensions of the lesion.171 Samii et al., who advocate the simple retrosigmoid route even for large petroclival meningiomas,36 recently described an elegant variant, the retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach in which the suprameatus petrous bone is drilled, thus providing access to Meckel’s cave and the middle fossa.37 Samii’s school is going to develop surgical “corridors” along the dural structures of the sphenopetroclival area to reach the lateral sellar compartment via the posterior fossa.55

Far Lateral–Combined Approach

The far lateral–combined approach combines the far lateral approach with subtemporal and transpetrosal exposures to gain an extensive view of the entire petroclival region for tumors involving the entire clivus and extending to the craniocervical region.172,173 The approach incorporates a subtemporal craniotomy and posterior petrous bone resection into the far lateral approach to obtain an unobstructed view of the entire clivus and ventral brain stem.

Surgical Adjuvants

• Vascular embolization: Preoperative embolization of the external carotid artery feeders can be helpful in reducing intraoperative bleeding.

• Intraoperative lumbar drainage of CSF: Drainage of CSF is an important adjuvant to facilitate brain relaxation.

• Intraoperative monitoring of the brain and cranial nerve functions: This monitoring includes somatosensory and motor evoked potentials, auditory brain stem evoked potential, and cranial nerves III, IV, VI, VII, X, XI, and XII.

• Frameless stereotactic navigation: This navigation aids surgical orientation, thus optimizing exposure and reducing risks, especially in complex approaches.

• Contact neodymium:yttrium–aluminum–garnet laser: This tool increases the chances of total removal, which can be achieved faster and with less bleeding.58

• Arterial bypass: When the tumor encases the petrous or cavernous carotid artery, if the patient fails the balloon occlusion test and vascular ligation is necessary, a vascular reconstruction is mandatory using a saphenous vein graft bypass or using an extracranial–intracranial arterial bypass.174

• Adequate reconstruction of the skull base to prevent CSF leakage: Reconstruction is done by placing a pericranial flap or autologous fat and biologic glue.

• Radiosurgery: Such surgery can be helpful for treating small remnants in critical areas.

• Postoperative hydroxyurea therapy: This therapy has been shown to stabilize and even reduce the size of residual petroclival meningiomas.175,176

Abdel Aziz K.M., Sanan A., van Loveren H.R., et al. Petroclival meningiomas: Predictive parameters for transpetrosal approaches. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:139-150.

Al-Mefty O., Kadri P.A., Hasan D.M. Anterior clivectomy: surgical technique and clinical applications. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(5):783-793.

Crockard H.A., Steel T., Plowman N., et al. A multidisciplinary team approach to skull base chordomas. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:175-183.

Dassoulas K., Schlesinger D., Yen C.P., Sheehan J. The role of Gamma Knife surgery in the treatment of skull base chordomas. J Neurooncol. 2009;94(2):243-248.

Dehdashti A.R., Karabatsou K., Ganna A. Expanded endoscopic endonasal approach for treatment of clival chordomas: early results in 12 patients. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(2):299-307.

Fatemi N., Dusick J.R., Gorgulho A.A., et al. Endonasal microscopic removal of clival chordomas. Surg Neurol. 2008;69(4):331-338.

Frank G., Sciarretta V., Calbucci F., et al. The endoscopic transnasal transsphenoidal approach for the treatment of cranial base chordomas and chondrosarcomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(1 suppl 1):ONS50-ONS57.

Fraser J.F., Nyquist G.G., Moore N. Endoscopic endonasal transclival resection of chordomas: operative technique, clinical outcome, and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Aug 21[Epub ahead of print]. 2009.

Hasegawa T., Ishii D., Kida Y., et al. Gamma Knife surgery for skull base chordomas and chondrosarcomas. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(4):752-757.

Kassam A.B., Snyderman C., Gardner P. The expanded endonasal approach: a fully endoscopic transnasal approach and resection of the odontoid process: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(suppl 1):E213.

Lang J. Skull Base Related Structures: Atlas of Clinical Anatomy. New York: Schattauer; 1995. 85-86

Maira G., Pallini R., Anile C., et al. Surgical treatment of clival chordomas: the transsphenoidal approach revisited. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:784-792.

Martin J.J., Niranjan A., Kondziolka D., et al. Radiosurgery for chordomas and chondrosarcomas of the skull base. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(4):758-764.

Pallini R., Maira G., Pierconti F., et al. Chordoma of the skull base: predictors of tumor recurrence. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:812-822.

Pallini R., Patel S., Salvinelli F., et al. Petroclival tumors. Anterolateral Approaches. In: Salvinelli F., De La Cruz A. Otoneurosurgery and Lateral Skull Base Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996:457-472.

Pillai P., Baig M.N., Karas C.S., Ammirati M. Endoscopic image-guided transoral approach to the craniovertebral junction: an anatomic study comparing surgical exposure and surgical freedom obtained with the endoscope and the operating microscope. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(5 suppl 2):437-442.

Samii A., Gerganov V.M., Herold C., et al. Chordomas of the skull base: surgical management and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(2):319-324.

Samii M., Tatagiba M., Carvalho G.A. Resection of large petroclival meningiomas by the simple retrosigmoid route. J Clin Neurosci. 1999;6:27-30.

Sekhar L.N., Schessel D.A., Bucur S.D., et al. Partial labyrinthectomy petrous apicectomy approach to neoplastic and vascular lesions of the petroclival area. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:537-550.

Sen C., Triana A.I., Berglind N. Clival chordomas: clinical management, results, and complications in 71 patients. J Neurosurg, Nov 20 [Epub ahead of print]. 2009.

Stippler M., Gardner P.A., Snyderman C.H., et al. Endoscopic endonasal approach for clival chordomas. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(2):268-277.

Tzortzidis F., Elahi F., Wright D. Patient outcome at long-term follow-up after aggressive microsurgical resection of cranial base chordomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(2):230-237.

Van Havenbergh T., Carvalho G., Tatagiba M., et al. Natural history of petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:55-62.

Vougioukas V.I., Hubbe U., Schipper J., et al. Navigated transoral approach to the cranial base and the craniocervical junction: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:247-250.

Yoneoka Y., Tsumanuma I., Fukuda M., et al. Cranial base chordoma—long term outcome and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir. 2008;150(8):773-778.

1. Sekhar L.N., Goel A., Sen C.N. Extradural clival tumors. In: Apuzzo M.L.J., editor. Brain Surgery: Complication Avoidance and Management. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1993:2221-2244.

2. Yasargil M.G., Mortara R.W., Curcic M.. Meningiomas of the posterior cranial fossa, Krayenbuhl H., editor, Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery, New York, Springer-Verlag, 1980;Vol 7:4-115.

3. Lang J. Anatomy of clivus. In: Samii M., Draf W. Surgery of the Skull Base. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1989:90-101.

4. Meyers S.P., Hirsch W.L., Curtin H.D., et al. Chondrosarcomas of the skull base: MR imaging features. Radiology. 1992;184:103-108.

5. Gay E., Sekhar L.N., Wright D.C. Chordomas and chondrosarcomas of the cranial base. In: Kaye A.H., Laws E.R.Jr. Brain Tumors. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1995:777-794.

6. Goel A. Chordomas and chondrosarcomas: relationship to the internal carotid artery. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;133:30-35.

7. Al-Mefty O., Fox J.L., Smith R.R. Petrosal approach for petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:510-517.

8. Bertalanffy H., Seeger W. The dorsolateral, suboccipital, transcondylar approach to the lower clivus and anterior portion of the craniocervical junction. Neurosurgery. 1991;129:815-821.

9. Bonnal J., Louis R., Combalbert A. L’abord temporal transtentoriel de l’angle ponto-cerebelleux et du clivus. Neurochirurgie. 1964;10:3-12.

10. Bricolo A., Turazzi S., Cristofori L., et al. Microsurgical removal of petroclival meningiomas: a report of 33 patients. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:813-828.

11. Cantore G.P., Ciappetta P., Delfini R. Choice of neurosurgical approach in the treatment of cranial base lesions. Neurosurg Rev. 1994;17:109-125.

12. Crockard H.A., Sen C.N. The transoral approach for the management of intradural lesions at the craniovertebral junction: review of 7 cases. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:88-98.

13. Derome P.J., Guiot G.. Surgical approaches to the sphenoidal and clival area, Krayenbuhl H., editor, Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery, New York, Springer-Verlag, 1979;Vol 6:101-136.

14. Fisch U., Kumar A. Infratemporal surgery of the skull base. In: Rand R.W., editor. Microneurosurgery. 3rd ed. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1985:421-454.

15. George B., Dematons C., Copignon J. Lateral approach to the anterior portion of the foramen magnum: application to surgical removal of 14 benign tumors: technical note. Surg Neurol. 1988;29:484-490.

16. Hardy J. L’abord transsphenoidal des tumeurs du clivus. Neurochirurgie. 1977;23:287-297.

17. Hakuba A., Liu S., Nishimura S. The orbitozygomatic infratemporal approach: a new surgical technique. Surg Neurol. 1986;26:271-276.

18. Hakuba A., Nishimura S., Jang B.J. A combined retroauricular and preauricular transpetrosal–transtentorial approach to clivus meningiomas. Surg Neurol. 1988;30:108-116.

19. Kawase T., Shiobara R., Toya S. Anterior transpetrosal–transtentorial approach for sphenopetroclival meningiomas: Surgical method and results in 10 patients. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:869-876.

20. Malis L.I.. Surgical resection of tumors of the skull base, Wilkins R.H., Rengashary S.S., editors, Neurosurgery, New York, McGraw-Hill, 1985;Vol 1:1011-1021.

21. Malis L. The petrosal approach. Clin Neurosurg. 1990;37:528-540.

22. Samii M., Ammirati M. The combined supratentorial presigmoid sinus avenue to the petroclival region: surgical technique and clinical applications. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1988;95:6-12.

23. Samii M., Ammirati M., Maharan A., et al. Surgery of petroclival meningiomas: report of 24 cases. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:12-17.

24. Sekhar L.N., Jannetta P.J., Burkhart L.E., et al. Meningiomas involving the clivus: a six year experience with 41 patients. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:764-781.

25. Sekhar L.N., Sen C.N., Snyderman C.H., et al. Anterior, anterolateral and lateral approaches to extradural petroclival tumors. In: Sekhar L.N., Janecka I.P. Surgery of Cranial Base Tumors. New York: Raven Press; 1993:157-223.

26. Sen C.N., Sekhar L.N. An extreme lateral approach to intradural lesions of the cervical spine and foramen magnum. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:197-204.

27. Spetzler R.F., Daspit C.P., Pappas C.T.E. The combined supra and infratentorial approach for lesions of the petrous and clival regions: experience with 46 cases. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:588-599.

28. Symon L. Surgical approaches to the tentorial hiatus. Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery. 1982;9:69-112.

29. Seifert V., Raabe A., Zimmermann M. Conservative (labyrinth-preserving) transpetrosal approach to the clivus and petroclival region—indications, complications, results and lessons learned. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2003;145:631-642.

30. Cho C.W., Al-Mefty O. Combined petrosal approach to petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:708-716.

31. Kirazli T., Oner K., Ovul L., et al. Petrosal presigmoid approach to the petro-clival and anterior cerebellopontine region (extended retro-labyrinthine, transtentorial approach). Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol (Bord). 2001;122(3):187-190.

32. Angeli S.I., De la Cruz A., Hitselberger W. The transcochlear approach revisited. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:690-695.

33. Roberti F., Sekhar L.N., Kalavakonda C., et al. Posterior fossa meningiomas: Surgical experience in 161 cases. Surg Neurol. 2001;56:8-20.

34. Horgan M.A., Delashaw J.B., Schwartz M.S., et al. Transcrusal approach to the petroclival region with hearing preservation: technical note and illustrative cases. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:660-666.

35. Abdel Aziz K.M., Sanan A., van Loveren H.R., et al. Petroclival meningiomas: Predictive parameters for transpetrosal approaches. Neurosurgery. 2000;47:139-150.

36. Samii M., Tatagiba M., Carvalho G.A. Resection of large petroclival meningiomas by the simple retrosigmoid route. J Clin Neurosci. 1999;6:27-30.

37. Samii M., Tatagiba M., Carvalho G.A. Retrosigmoid intradural suprameatal approach to Meckel’s cave and the middle fossa: surgical technique and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:235-241.

38. Goel A. Extended lateral subtemporal approach for petroclival meningiomas: Report of experience with 24 cases. Br J Neurosurg. 1999;13:270-275.

39. Lang D.A., Neil-Dwyer G., Garfield J. Outcome after complex neurosurgery: the caregiver’s burden is forgotten. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:359-363.

40. Spallone A., Makhmudov U.B., Mukhamedjanov D.J., et al. Petroclival meningioma: an attempt to define the role of skull base approaches in their surgical management. Surg Neurol. 1999;51:412-419.

41. Sekhar L.N., Schessel D.A., Bucur S.D., et al. Partial labyrinthectomy petrous apicectomy approach to neoplastic and vascular lesions of the petroclival area. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:537-550.

42. MacDonald J.D., Antonelli P., Day A.L. The anterior subtemporal, medial transpetrosal approach to the upper basilar artery and ponto-mesencephalic junction. Neurosurgery. 1998;43:84-89.

43. Babu R.P., Sekhar L.N., Wright D.C. Extreme lateral transcondylar approach: Technical improvements and lessons learned. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:49-59.

44. Vougioukas V.I., Hubbe U., Schipper J., et al. Navigated transoral approach to the cranial base and the craniocervical junction: technical note. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:247-250.

45. de Divitiis E., Cappabianca P., Cavallo L.M. Endoscopic transsphenoidal approach: adaptability of the procedure to different sellar lesions. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:699-705.

46. Crockard H.A., Cheeseman A., Steel T., et al. A multidisciplinary team approach to skull base chondrosarcomas. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:184-189.

47. Crockard H.A., Steel T., Plowman N., et al. A multidisciplinary team approach to skull base chordomas. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:175-183.

48. Colli B., Al-Mefty O. Chordomas of the craniocervical junction: follow-up review and prognostic factors. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:933-943.

49. Mortini P., Mandelli C., Franzin A., et al. Surgical excision of clival tumors via the enlarged transcochlear approach: indications and results. J Neurosurg Sci. 2001;45:127-139.

50. Colreavy M.P., Baker T., Campbell M., et al. The safety and effectiveness of the Le Fort I approach to removing central skull base lesions. Ear Nose Throat J. 2001;80:315-320.

51. Bejjani G.K., Sekhar L.N., Riedel C.J. Occipitocervical fusion following the extreme lateral transcondylar approach. Surg Neurol. 2000;54:109-115.

52. Diaz-Gonzalez F.J., Padron A., Foncea A.M., et al. A new transfacial approach for lesions of the clivus and parapharyngeal space: the partial segmented Le Fort I osteotomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:955-959.

53. Nakase H., Ohnishi H., Matsuyama T., et al. Two-stage skull base surgery for tumours extending to the sub- and epidural spaces. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1998;140:891-898.

54. Carpentier A., Polivka M., Blanquet A., et al. Suboccipital and cervical chordomas: the value of aggressive treatment at first presentation of the disease. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:1070-1077.

55. Iaconetta G., Fusco M., Samii M. The sphenopetroclival venous gulf: a microanatomical study. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:366-375.

56. Chanda A., Nanda A. Partial labyrinthectomy petrous apicectomy approach to the petroclival region: An anatomic and technical study. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:147-159.

57. Ozveren M.F., Uchida K., Aiso S., et al. Meningovenous structures of the petroclival region: Clinical importance for surgery and intravascular surgery. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:829-836.

58. Maira G., Anile C., Vignati A., et al. Advances in treatment of supra-tentorial meningiomas of the skull base by microsurgical and laser techniques. In: Samii M., editor. Skull Base Surgery. Basel: Karger; 1994:190-193.

59. Hirohata M., Abe T., Morimitsu H., et al. Preoperative selective internal carotid artery dural branch embolisation for petroclival meningiomas. Neuroradiology. 2003;45:656-660.

60. Schul C., Wassmann H., Skopp G.B., et al. Surgical management of intraosseous skull base tumors with aid of Operating Arm System. Comput Aided Surg. 1998;3:312-319.

61. Villavicencio A.T., Gray L., Leveque J.C., et al. Utility of three-dimensional computed tomographic angiography for assessment of relationships between the vertebrobasilar system and the cranial base. Neurosurgery. 2001;48:318-326.

62. Kocaogullar Y., Avci E., Fossett D., et al. The extradural subtemporal keyhole approach to the sphenocavernous region: anatomic considerations. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2003;46:100-105.

63. Prevedello D.M., Doglietto F., Jane J.A.Jr., et al. History of endoscopic skull base surgery: its evolution and current reality. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(1):206-213.

64. Frank G., Sciarretta V., Calbucci F. The endoscopic transnasal transsphenoidal approach for the treatment of cranial base chordomas and chondrosarcomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(1 suppl 1):ONS50-ONS57.

65. Kassam A., Snyderman C.H., Mintz A. Expanded endonasal approach: the rostrocaudal axis. Part II. Posterior clinoids to the foramen magnum. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19(1):E4.

66. Kassam A., Snyderman C.H., Mintz A. Expanded endonasal approach: the rostrocaudal axis. Part I. Crista galli to the sella turcica. Neurosurg Focus. 2005;19(1):E3.

67. Stippler M., Gardner P.A., Snyderman C.H., et al. Endoscopic endonasal approach for clival chordomas. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(2):268-277.

68. Dehdashti A.R., Karabatsou K., Ganna A. Expanded endoscopic endonasal approach for treatment of clival chordomas: early results in 12 patients. Neurosurgery. 2008;63(2):299-307.

69. Hong Jiang W., Ping Zhao S., Hai Xie Z., et al. Endoscopic resection of chordomas in different clival regions. Acta Otolaryngol. 2009;129(1):71-83.

70. Zhang Q., Kong F., Yan B. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for clival chordoma and chondrosarcoma. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 2008;70(2):124-129.

71. Fraser J.F., Nyquist G.G., Moore N. Endoscopic endonasal transclival resection of chordomas: operative technique, clinical outcome, and review of the literature. J Neurosurg Aug 21[Epub ahead of print]. 2009.

72. de Almeida J.R., Zanation A.M., Snyderman C.H., et al. Defining the nasopalatine line: the limit for endonasal surgery of the spine. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(2):239-244.

73. Lang J. Skull Base and Related Structures: Atlas of Clinical Anatomy. New York: Schattauer; 1995. 85-86

74. Harsh G.R., Sekhar L.N. The subtemporal, transcavernous, anterior transpetrosal approach to the upper brain stem and clivus. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:709-717.

75. Day J.D., Koos W.T., Matula C., et al, Color Atlas of Microneurosurgical Approaches, New York, Thieme, 1997 :Vol 1 160-171

76. Sekhar L.N., Goel A. Intradural clival lesion. In: Apuzzo M.L.J., editor. Brain Surgery: Complication Avoidance and Management. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1993:2245-2264.

77. Saeger W., Ludecke D.K., Muller S., et al. Chordome des clivus: histologie, Ultrastruktur und Klinik. Tumor Diagnostik Therapie. 1983;4:74-79.

78. Pallini R., Maira G., Pierconti F., et al. Chordoma of the skull base: predictors of tumor recurrence. J Neurosurg. 2003;98:812-822.

79. Goel A., Kobayashi S. Chordomas: A clinical review. In: Kobayashi S., Goel A., Hongo K. Neurosurgery of Complex Tumors and Vascular Lesions. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:293-306.

80. Chambers P.W., Schwinn C.P. A clinicopathologic study of metastasis. Am J Clin Pathol. 1979;72:765-776.

81. Deniz M.L., Kilic T., Almaata I., et al. Expression of growth factors and structural proteins in chordomas: basic fibroblast growth factor, transforming growth factor alpha, and fibronectin are correlated with recurrence. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:753-760.

82. Rosenberg A.E., Nielsen G.P., Keel S.B., et al. Chondrosarcoma of the base of the skull: a clinicopathologic study of 200 cases with emphasis on its distinction from chordoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1999;23:1370-1378.

83. Crumley R.L., Gutin P.H. Surgical access for clivus chordoma: the University of California, San Francisco, experience. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;115:295-300.

84. Maira G., Pallini R., Anile C., et al. Surgical treatment of clival chordomas: The transsphenoidal approach revisited. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:784-792.

85. Sen C., Triana A.I., Berglind N. Clival chordomas: clinical management, results, and complications in 71 patients. J Neurosurg, Nov 20 [Epub ahead of print]. 2009.

86. Tzortzidis F., Elahi F., Wright D. Patient outcome at long-term follow-up after aggressive microsurgical resection of cranial base chordomas. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(2):230-237.

87. Al-Mefty O., Fox J.L., Rifai A., et al. A combined infratemporal and posterior fossa approach for the removal of giant glomus tumors and chondrosarcomas. Surg Neurol. 1987;28:423-431.

88. Canalis R.F., Black K., Martin N., et al. Extended retrolabyrinthine transtentorial approach to petroclival lesions. Laryngoscope. 1991;101:6-13.

89. Gay E., Sekhar L.N., Rubinstein E., et al. Chordomas and chondro-sarcomas of the cranial base: results and follow-up of 60 patients. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:887-897.

90. Goel A. Extended middle fossa approach for petroclival lesions. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;135:78-83.

91. Sen C.N., Sekhar L.N., Schramm V.L., et al. Chordoma and chondro-sarcoma of the cranial base: an 8-year experience. Neurosurgery. 1989;25:931-941.

92. Lalwani A.K., Kaplan M.J., Gutin P.H. The transsphenoethmoid approach to the sphenoid sinus and clivus. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:1008-1014.

93. Laws Jr E.R. Transsphenoidal surgery for tumors of the clivus. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1984;92:100-101.

94. Laws E.R.Jr. Clivus chordomas. In: Sekhar L.N., Janecka I.P. Surgery of Cranial Base Tumors. New York: Raven Press; 1993:679-685.

95. Raffel C., Wright D.C., Gutin P.H., et al. Cranial chordomas: Clinical presentation and results of operative and radiation therapy in twenty-six patients. Neurosurgery. 1985;17:703-710.

96. Rougerie J., Guiot G., Bouche J., et al. Les voies d’abord du chordome du clivus. Neurochirurgie. 1967;13:559-570.

97. Jung H.W., Yoo H., Paek S.H., et al. Long-term outcome and growth rate of subtotally resected petroclival meningiomas: experience with 38 cases. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:567-574.

98. Fatemi N., Dusick J.R., Gorgulho A.A., et al. Endonasal microscopic removal of clival chordomas. Surg Neurol. 2008;69(4):331-338.

99. Al-Mefty O., Kadri P.A., Hasan D.M. Anterior clivectomy: surgical technique and clinical applications. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(5):783-793.

100. Samii A., Gerganov V.M., Herold C., et al. Chordomas of the skull base: surgical management and outcome. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(2):319-324.

101. Harris J.P., Godin M.S., Krekorian T.D., et al. The transoropalatal approach to the atlantoaxial-clival region: considerations for the head and neck surgeon. Laryngoscope. 1989;99:467-474.

102. Menezes A.H., VanGilder J.C. Transoral–transpharyngeal approach to the anterior craniocervical junction: ten-year experience with 72 patients. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:895-903.

103. Price J.C. The midfacial degloving approach to the central skull base. Ear Nose Throat J. 1986;65:174-180.

104. Sekhar L.N., Nanda A., Sen C.N., et al. The extended frontal approach to tumors of the anterior, middle, and posterior skull base. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:198-206.

105. Williams W.G., Lo L.J., Chen Y.R. The Le Fort I—palatal split approach for skull base tumors: efficacy, complications, and outcome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:2310-2319.

106. Rabadan A., Conesa H. Transmaxillary–transnasal approach to the anterior clivus: a microsurgical anatomical model. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:473-481.

107. Swearingen B., Joseph M., Cheney M., et al. A modified transfacial approach to the clivus. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:101-105.

108. Janecka I.P., Sen C.N., Sekhar L.N., et al. Facial translocation: a new approach to the cranial base. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;103:413-419.

109. James D., Crockard H.A. Surgical access to the base of the skull and upper cervical spine by exterior maxillotomy. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:411-416.

110. Anand V.K., Harkey H.L., Al-Mefty O. Open-door maxillotomy approach for lesions of the clivus. Skull Base Surg. 1991;1:217-225.

111. Stevenson G.C., Stoney R.J., Perkins R.K., et al. A transcervical transclival approach to the ventral surface of the brain stem for removal of a clivus chordoma. J Neurosurg. 1996;24:544-551.

112. George B., Lot G., Velut S., et al. Pathologie tumoral du foramen magnum. Neurochirurgie. 1993;39(suppl 1):1-89.

113. Sasaki C.T., Lowlicht R.A., Astrachan D.I., et al. Le Fort I osteotomy approach for skull base tumors. Laryngoscope. 1990;100:1073-1076.

114. Bowles A.P., Al-Mefty O. The transmaxillary approach to clival chordomas. In: Al-Mefty O., Origitano T.C., Harkey H.L. Controversies in Neurosurgery. New York: Thieme; 1996:115-121.

115. Joseph M. Pedicled rhinotomy for exposure of the clivus. In: Schmidek H.H., Sweet W.H. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1995:469-475.

116. Al-Mefty O., Borba L.A., Aoki N., et al. The transcondylar approach to extradural nonneoplastic lesions of the craniovertebral junction. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:1-6.

117. Zanation A.M., Snyderman C.H., Carrau R.L., et al. Endoscopic endonasal surgery for petrous apex lesions. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(1):19-25.

118. Hardy J. Transsphenoidal microsurgery of the normal and pathological pituitary. Clin Neurosurg. 1969;16:185-217.

119. Hardy J. Transsphenoidal microsurgery of prolactinomas: Report on 355 cases. In: Tolis G., Stefanis C., Mountokalakis T., et al. Prolactin and Prolactinomas. New York: Raven Press; 1983:431-440.

120. Maira G., Anile C., De Marinis L., et al. Prolactin-secreting adenomas: surgical results and long-term follow-up. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:736-743.

121. Maira G., Anile C., Rossi G.F., et al. Surgical treatment of craniopharyngiomas: an evaluation of the transsphenoidal and pterional approaches. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:715-724.

122. Esposito F., Dusick J.R., Fatemi N., Kelly D.F. Graded repair of cranial base defects and cerebrospinal fluid leaks in transsphenoidal surgery. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(4 suppl 2):295-303.

123. Miller E., Crockard H.A. Transoral transclival removal of anteriorly placed meningiomas at the foramen magnum. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:966-968.

124. Mullan S., Naunton R., Hekmat-Panach J., et al. The use of an anterior approach to ventrally placed tumours in the foramen magnum and vertebral column. J Neurosurg. 1966;24:536-543.

125. Delgado T.E., Garrido E., Harwick R. Labiomandibular, transoral approach to chordomas in the clivus and upper spine. Neurosurgery. 1981;8:675-679.

126. Gutkelch A.N., Williams R.G. Anterior approach to recurrent chordomas of the clivus. Neurosurgery. 1972;36:670-672.

127. Krayenbuhl H., Yasargil M.G. Chondromas. Progr Neurol Surg. 1975;6:435-463.

128. Doglietto F., Lauretti L., Frank G., et al. Microscopic and endoscopic extracranial approaches to the cavernous sinus: anatomic study. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(5 suppl 2):413-421.

129. Frempong-Boadu A.K., Faunce W.A., Fessler R.G. Endoscopically assisted transoral–transpharyngeal approach to the craniovertebral junction. Neurosurgery. 2002;51(suppl 5):S60-S66.

130. Kassam A.B., Snyderman C., Gardner P. The expanded endonasal approach: a fully endoscopic transnasal approach and resection of the odontoid process: technical case report. Neurosurgery. 2005;57(suppl 1):E213.

131. Pillai P., Baig M.N., Karas C.S., Ammirati M. Endoscopic image-guided transoral approach to the craniovertebral junction: an anatomic study comparing surgical exposure and surgical freedom obtained with the endoscope and the operating microscope. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(5 suppl 2):437-442.

132. Derome P., Visot A., Monteil J.P., et al. Management of cranial chordomas. In: Sekhar L.N., Schramm V.L. Tumors of the Cranial Base. Mount Kisco: Futura; 1987:607-622.

133. Pallini R., Patel S., Salvinelli F., et al. Petroclival tumors. Anterolateral approaches. In: Salvinelli F., De La Cruz A. Otoneurosurgery and Lateral Skull Base Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996:457-472.

134. Perneczky A. The posterolateral approach to the foramen magnum. In: Samii, editor. Surgery In and Around the Brain Stem and Third Ventricle. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1986:460-466.

135. Spetzler R.F., Graham T.W. The far lateral approach to the inferior clivus and upper cervical region: technical note. BNI Q. 1990;6:35-38.

136. Heffelfinger M.J., Dahlin D.C., MacCarty C.S., et al. Chordomas and cartilaginous tumors at the skull base. Cancer. 1973;32:410-420.

137. Kondziolka D., Lunsford L.D., Flickinger J.C. The role of radiosurgery in the management of chordoma and chondrosarcoma of the cranial base. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:38-46.

138. Samii M.. Comments, Gay E., Sekhar L.N., Rubinstein E., et al. Chordomas and chondrosarcomas of the cranial base: results and follow-up of 60 cases. Neurosurgery. 1995;36:896-897.

139. Suit H.D., Goitein M., Munzenrider J., et al. Definitive radiation therapy for chordoma and chondrosarcoma of base of skull and cervical spine. J Neurosurg. 1982;56:377-385.

140. Keisch M.E., Garcia D.M., Shibuya R.B. Retrospective long-term follow-up analysis in 21 patients with chordoma of various sites treated at a single institution. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:374-377.

141. Austin-Seymour M., Muzenrider J., Goitein M., et al. Fractionated proton radiation therapy of chordoma and low-grade chondrosarcoma of the base of the skull. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:13-17.

142. Crockard A., Macaulay E., Plowman P.N. Stereotactic radiosurgery. VI: Posterior displacement of the brainstem facilitates safer high dose radiosurgery for clival chordoma. Br J Neurosurg. 1999;13:65-70.

143. Schulz-Ertner D., Haberer T., Jakel O., et al. Radiotherapy for chordomas and low-grade chondrosarcomas of the skull base with carbon ions. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;53:36-42.

144. Neeman Z., Patti J.W., Wood B.J. Percutaneous radiofrequency ablation of chordoma. Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1330-1332.

145. Dassoulas K., Schlesinger D., Yen C.P., Sheehan J. The role of Gamma Knife surgery in the treatment of skull base chordomas. J Neurooncol. 2009;94(2):243-248.

146. Yoneoka Y., Tsumanuma I., Fukuda M., et al. Cranial base chordoma—long term outcome and review of the literature. Acta Neurochir. 2008;150(8):773-778.

147. Hasegawa T., Ishii D., Kida Y., et al. Gamma Knife surgery for skull base chordomas and chondrosarcomas. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(4):752-757.

148. Martin J.J., Niranjan A., Kondziolka D., et al. Radiosurgery for chordomas and chondrosarcomas of the skull base. J Neurosurg. 2007;107(4):758-764.

149. Krishnan S., Foote R.L., Brown P.D., et al. Radiosurgery for cranial base chordomas and chondrosarcomas. Neurosurgery. 2005;56(4):777-784.

150. Van Havenbergh T., Carvalho G., Tatagiba M., et al. Natural history of petroclival meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:55-62.

151. Goel A., Nitta J., Kobayashi S. Surgical approaches to clival lesions. In: Kobayashi S., Goel A., Hongo K. Neurosurgery of Complex Tumors and Vascular Lesions. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:181-210.

152. Al-Mefty O. Operative Atlas of Meningiomas. Philadelphia: Lippincott Raven; 1998.

153. Long D.M. Surgical approaches to tumors of skull base: An overview. In: Wilkins R.H., Rengachary S.S. Neurosurgery Update. I: Diagnosis, Operative Technique and Neuro-oncology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1990:266-276.

154. Sekhar L.N., Javed T., Jannetta P.J. Petroclival meningiomas. In: Sekhar L.N., Janecka I.P. Surgery of Cranial Base Tumors. New York: Raven Press; 1993:605-659.

155. Luyendijk W.. Operative approaches to the posterior fossa, Krayenbuhl H., editor, Advances and Technical Standards in Neurosurgery, New York, Springer-Verlag, 1976;Vol 3:81-101.

156. Mayberg M.R., Symon L. Meningiomas of the clivus and apical petrous bone: report of 35 cases. J Neurosurg. 1986;65:160-167.

157. Samii M., Draf W. Surgery of the Skull Base. Berlin: Springer-Verlag; 1989. 209-348

158. Cantore G.P., Delfini R., Ciappetta P. Surgical treatment of petroclival meningiomas: experience with 16 cases. Surg Neurol. 1994;42:105-111.

159. King T.T. Combined translabyrinthine-transtentorial approach to acoustic nerve tumors. Proc R Soc Med. 1970;63:780-782.

160. Kawase T., Toya S., Shiobara R., et al. Transpetrosal approach for aneurysms of the lower basilar artery. J Neurosurg. 1985;63:857-861.

161. Al-Mefty O. Surgery of the Cranial Base. Boston: Kluwer; 1988. 239-258

162. Sen C.N., Sekhar L.N. The subtemporal and preauricular infratemporal approach to intradural structures ventral to the brain stem. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:345-354.

163. Sekhar L.N., Pomeranz S., Janecka I.P., et al. Temporal bone neoplasms: a report on 20 surgically treated cases. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:578-587.

164. Taniguchi M., Perneczky A. Subtemporal keyhole approach to the suprasellar and petroclival region: microanatomic considerations and clinical applications. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:592-601.

165. Miller C.G., van Loveren H.R., Keller J.T., et al. Transpetrosal approach: surgical anatomy and technique. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:461-469.

166. Pellerin P., Lesoin F., Dhellemmes P., et al. Usefulness of the orbitofrontomalar approach associated with bone reconstruction for frontotemporosphenoid meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1984;15:715-718.

167. Zabramski J.M., Kiris T., Sankhla S.K., et al. Orbitozygomatic craniotomy: technical note. J Neurosurg. 1998;89:336-341.

168. Hakuba A., Nishimura A., Tanaka K., et al. Clivus meningiomas: six cases of total removal. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1977;17:63-77.

169. Hirsch B.E., Cass S.P., Sekhar L.N., et al. Translabyrinthine approach to skull base tumors with hearing preservation. Am J Otol. 1993;14:533-543.

170. House W.F., Hitselberger W.E. The transcochlear approach to the skull base. Arch Otolaryngol. 1976;102:334.

171. Lang J.Jr., Samii M. Retrosigmoidal approach to the posterior cranial fossa: an anatomical study. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1991;111:147-153.

172. Baldwin H.Z., Miller C.G., van Loveren H.R., et al. The far lateral–combined supra- and infratentorial approach: a human cadaveric prosection model for routes of access to the petroclival region and ventral brain stem. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:60-68.

173. Baldwin H.Z., Spetzler R.F., Wascher T.M., et al. The far lateral–combined supra- and infratentorial approach: clinical experience. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;134:155-158.

174. Linskey M.E., Sekhar L.N., Sen C. Cerebral revascularization in cranial base surgery. In: Sekhar L.N., Janecka I.P. Surgery of Cranial Base Tumors. New York: Raven Press; 1993:45-68.

175. Schrell U.M., Rittig M.G., Anders M., et al. Hydroxyurea for treatment of unresectable and recurrent meningiomas. II: decrease in the size of meningiomas in patients treated with hydroxyurea. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:840-844.

176. Mason W.P., Gentili F., Macdonald D.R., et al. Stabilization of disease progression by hydroxyurea in patients with recurrent or unresectable meningioma. J Neurosurg. 2002;97:341-346.