Chapter 194 Surgical Management of Cerebrospinal Fluid Leakage after Spinal Surgery

Incidence and Prevalence

Dural tears with CSF leaks are well-documented common complications of spinal surgeries. However, the incidence rate is hypothesized to be underreported because of the lack of associated morbidity with most dural tears. Thus, the prevalence is largely debated, but has been reported to be 0.5% to 18%.1,2 The prevalence of CSF leaks is higher in patients undergoing revision surgery. The occurrence and management of CSF leaks are specific to the region and the surgical approach.

Specific Regions and Surgical Approaches

The lumbosacral region is noted as the most common location for dural injuries due to the region anatomy as well as its common location for spinal surgeries.1,2 Many conditions facilitate dural tears including thinned dura, prior spinal surgery, dural fibrosis, spinal stenosis, and spinal bifida.3,4 Additionally, ossifications of spinal ligament, high-speed drill, and synovial cysts have been associated with dural tears.4,5 Numerous mechanisms such as trauma, disc fragments, bone spikes, excessive dural traction and iatrogenic laceration by sharp instruments or intradural explorations have led to CSF leaks with several dramatic consequences.3,6 Potentially, leaks can lead to pseudomeningocele formation, intracranial hypotension, neural element herniation with pain and neurologic deficits, wound dehiscence, fistula formation, and infection.1,7,8 Therefore, any CSF leak warrants immediate repair.

CSF leakage in extradural operation frequently happens during a severe spinal cord stenosis decompression or reoperation with associated scar tissue. In a virgin spine without prior surgery, the bony structures should be removed initially with a Leksell rongeur and a high-speed drill superficial to the ligamentum flavum for further dural protection. Ideally the drill should be used in a medial to lateral fashion to reduce incidence of slippage and tear. Proper and adequate dural separation from the overlaying fascia and lamina must be performed to reduce the incidence of any dural tear, which is most commonly caused by dura being caught between the Kerrison rongeur footplate and the bone. Therefore, a fine dissecting instrument such as angled curette or Woodson dissectors should be utilized before placement of a cutting instrument in the epidural space. This exercise becomes even more important in a reoperation case as there is associated scar formation and it can be adherent to dura. A 3% to 5% higher rate of duratomy has been reported in a revision case.1,2,9 It is recommended that the laminectomy be extended to obtain a nonoperated segment of dura and operate from normal to abnormal (scar) anatomy. If the scar is easily dissected from the dura then a blunt dissector may be utilized, otherwise sharp dissection may be needed for safe exploration.

Use of spinal instruments as well as bony spikes are reported causes of delayed CSF leaks.10 Medial placement of pedicle screws or deep placement of anterior spinal fusion plating screws can lead to dural injures with late presentation of CSF leak symptoms. In these scenarios, CSF leaks may not be noted during the surgery or may not even exist in the case of injury with bony spikes. Special attention must be made to proper length and placement of screw and prevention of bony spicule by smoothing the bony edges. In case of a surgical repair, extension of bony decompression may be warranted in order to directly expose the dural injury for adequate visualization and repair. Also, intraoperative Valsalva maneuver and tilting of the table to increase the depended position of durotomy can help in direct evaluation of the dura.

The relative risk of developing an intraoperative inadvertent dural tear using an anterior procedure has been reported to be increased in patients undergoing corpectomy, fusion, surgical management of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL) and revision. Dural injuries during anterior spinal operations follow the same principles as previously mentioned. Proper and careful dural dissection in addition to adequate bony exposure is essential to prevent and repair leaks in these approaches. However, special attention must be given to cases involving ossification of posterior longitudinal ligaments, as dural injuries in the cervical spine are most prevalent in the presence of OPLL.4 These patients are 13.7 times more likely to have CSF leak during their spinal surgeries.5 If a laceration occurs and warrants a suture repair, dura should be carefully dissected parallel to its fiber. However, following the removal of the posterior longitudinal ligament, a dural gap is most often created which requires a patch. Occasionally, this gap may not be completely covered in which case it can be sewn onto the dura as much as possible with the remainder of the defect being sealed with fat, muscle, and fibrin glue.

Diagnosis

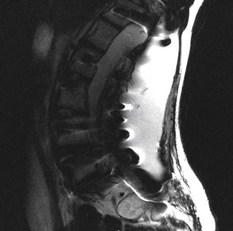

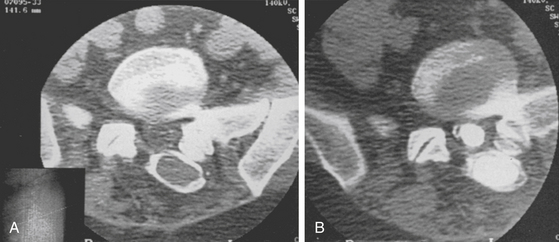

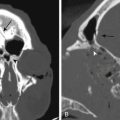

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) remains the gold standard to diagnose a CSF leak. The only difficulty may be in distinguishing between CSF and seroma fluid. Overall, MRI helps to delineate the location, extent, and characteristics of the lesion. Specifically, CSF is hypointense on T1-weighted images and hyperintense on T2-weighted images. Fluid collections in this pattern that seem to be extravasating from the spinal canal should raise suspicion of a pseudomeningocele (Fig. 194-1). In lieu of a MRI, computed tomography (CT), myelography, and radionuclide myelography may be adjunctive imaging modalities (Fig. 194-2).

Treatment

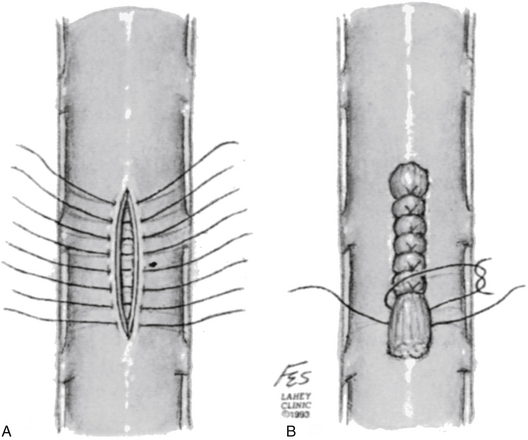

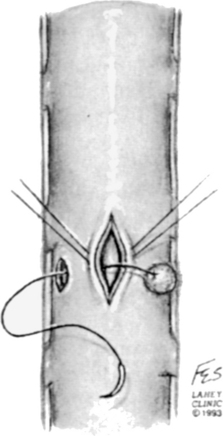

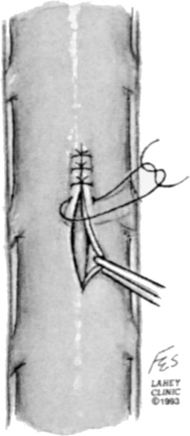

The detection of CSF secondary to a dural tear during spinal surgery may be visualized intraoperatively or postoperatively. If, intraoperatively, the egress of CSF from a dural laceration is seen, the site of the dural laceration should be located. Occasionally, the site of the dural defect may be underneath overlying bone. In this case, the overlying bone should be removed if possible to expose the entire length of the dural defect in order to allow for a watertight closure. A 5-0 or 6-0 synthetic braided or monofilament suture is recommended with a running or interrupted stitch.11 An interrupted stitch allows tension to be maintained on the suture line required for a watertight closure, whereas with a running stitch the tension on the suture line can be disrupted should the suture break or the stitch unravel (Fig. 194-3).

FIGURE 194-3 Primary closure of dural defect using interrupted sutures.

(Courtesy of the Lahey Clinic, Burlington, MA.)

If the dura is thin and friable, additional problems may arise during the repair of the dural defect. The holes created in the dura by the needle during placement of the dural stitch may also leak CSF. In addition, the dura may tear when tension is applied by the sutures across the suture line. One technique that may be helpful in these cases is to tie the sutures over a pledget of muscle.11 All the sutures are first placed across the suture line. A strip of muscle is then placed over the dural defect and the sutures are then tied over the muscle11 (Fig. 194-4).

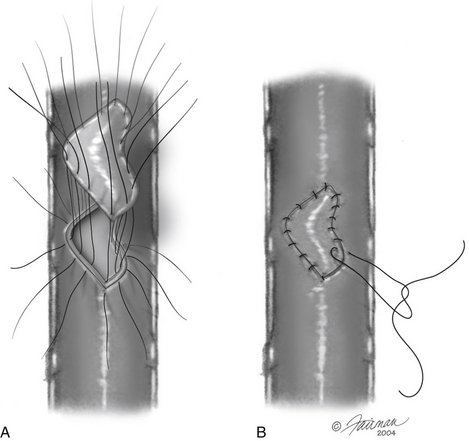

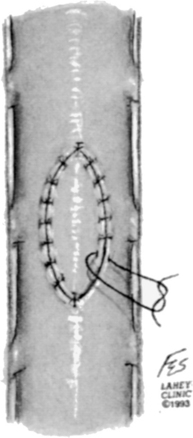

In the case of a large dural defect that cannot be easily approximated, a dural patch may be necessary. Autologous fascia from the wound or fascia lata may be used. Additionally, synthetic dural patch material such as Alloderm or Durepair may be used. The dural patch is anchored to the corners of the dural defect. The patch is then anchored to the edges of the dural defect with an interrupted or running suture (Fig. 194-5). If significant difficulty is encountered with this technique, a “parachute” technique may prove successful, in which all the sutures are first placed through the graft and the dural edge.11 The graft is then placed into position and all sutures are then tied (Fig. 194-6).

FIGURE 194-5 Closure of a large dural defect using a patch sewn in place with interrupted sutures.

(Courtesy of the Lahey Clinic, Burlington, MA.)

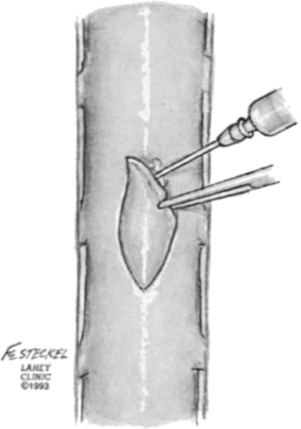

Holes in the dura that are difficult to suture primarily can be closed with a small amount of muscle covering the hole and then sutured into place. Alternatively, a technique has been described involving the creation of a small midline durotomy.17 A suture with a small piece of muscle anchored to its end can then be passed through the durotomy and out the hole, thereby closing the hole from the inside. The muscle is then tied in place and the midline durotomy is closed primarily (Fig. 194-7).

Once the defect is sutured closed (either primarily or with a dural patch), sealing the edges with an adhesive such as a fibrin glue has been shown to be advantageous in preventing a postoperative CSF leak (Fig. 194-8). Tisseel (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL) is a fibrin sealant that has been effectively used at many institutions for this purpose (Fig. 194-9). However, some studies have shown no statistical difference in the development of a CSF leak in those cases in which fibrin glue was used versus those in which fibrin glue was not used.12

FIGURE 194-8 Application of fibrin glue to the dural patch and dural edges to hold the graft in place.

(Courtesy of the Lahey Clinic, Burlington, MA.)

FIGURE 194-9 Postoperative magnetic resonance image from the patient in Fig. 194-1 after pseudomeningocele drainage, muscle flap and Tisseel repair of cerebrospinal fluid leak. Note significant reduction in pseudomeningocele size without evidence of reaccumulation. Air is noted in the pseudomeningocele cavity.

At times, direct repair of a dural tear cannot be accomplished. This may occur if the dura is extremely friable or if the defect is in a location that cannot be readily accessed. In these cases, CSF diversion, such as placement of a lumbar drain, may allow pressure to be diverted away from the dural defect, allowing it to heal.11 This should be accompanied with a multilayered soft tissue closure and a watertight skin closure to prevent a CSF cutaneous fistula. Additionally, care should be taken not to allow overdrainage of CSF through the lumbar drain, as this may result in a downward herniation of the cerebellar tonsils and brain stem.

Several institutions have placed subfascial drains at the time of surgery to expedite the closure of a dural defect. One study examined the effectiveness of the placement of a subfascial Jackson-Pratt (JP) drain in resolving CSF leaks.13 At the time of surgery, a JP drain was placed, drains were left in 10 to 17 days postoperatively, and the output was monitored. If a leak was present, the drain would provide continuous evacuation of the CSF, thereby allowing the dura and overlying soft tissues to heal. Data in this series showed improved resolution of CSF leaks using this intervention.

Despite the above measures, a CSF leak may still be encountered postoperatively. In this circumstance, many argue that the patient should undergo re-exploration and repair of the dural defect, especially if there is a development of a tense pseudomeningocele or wound breakdown.11 Surgical re-exploration allows the advantage of direct visualization of the leak and drainage of the pseudomeningocele, as well as direct repair using the methods mentioned above (Fig. 194-10). However, nonoperative strategies have also been implemented. Traditional strategies include bed rest, use of acetazolamide, and avoidance of straining or activities that may increase intracranial pressure.13 Several institutions advocate bed rest in the postoperative period, since flat bed rest is thought to reduce the amount of pressure exerted by the CSF on the dural tear. In some cases, if the CSF leak is small, the skin incision at the area of the leak may be oversewn. The use of prophylactic antibiotics to prevent meningitis has been debated, since this practice may select for resistant strains of bacteria. One series showed termination of a CSF leak within 10 to 28 days by implementing a watertight skin closure with daily subcutaneous taps of the pseudomeningocele and Trendelenburg position.14 Another series demonstrated good results by employing a multilayered watertight closure of the soft tissues and the postoperative use of mannitol and flat bed rest.15

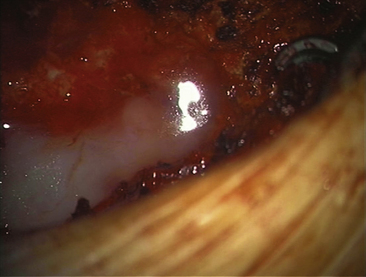

FIGURE 194-10 Intraoperative photograph of the application of Tisseel to the dural surface as an adjunct to primary repair.

Finally, a lumbar drain can be placed postoperatively if a CSF leak is detected. In a series of 17 patients with postoperative CSF leaks, 14 of those patients showed complete resolution of the leak after drainage of CSF for 4 days via a lumbar drain.16 Placement of a lumbar drain may be complicated by nausea and vomiting, as well as an intradural infection, at which point the lumbar catheter must be removed and antibiotics initiated.

Summary

Postoperative spinal surgery CSF leaks may be prevented by standard surgical techniques and postoperative imaging studies. Observed durotomies should be managed immediately by an attempt at a watertight closure under microscopic magnification. Despite the fact that most leaks are asymptomatic, they warrant aggressive monitoring and management. The potential morbidity, such as meningitis and subsequent prolonged hospitalization, can be prevented. Nonoperative management strategies exist; however, re-exploration and primary closure of the dural defect remains as the standard of care for the management of a postoperative CSF leak.

Bosacco S.J., Gardner M.J., Guille J.T. Evaluation and treatment of dural tears in lumbar spine surgery: a review. Clin Orthop. 2001;389:238-247.

Cammisa F.P.Jr., Girardi F.P., Sangani P.K., et al. Incidental durotomy in spine surgery. Spine. 2000;25:2663-2667.

Faraj A.A., Webb J.K. Early complications of spinal pedicle screw. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:324-326.

Fountas K.N., Kapsalaki E.Z., Johnston K.W. Cerebrospinal fluid fistula secondary to dural tear in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: case report. Spine. 2005;30:E277-E280.

Freidberg S. Surgical management of cerebrospinal fluid leakage after spinal surgery. In: Schmidek H.H., Sweet W.H. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005:2147-2152.

Hannallah D., Lee J., Khan M., et al. Cerebrospinal fluid leaks following cervical spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1101-1105.

Hughes S., Ozqur B.M., German M., Taylor W.R. Prolonged Jackson-Pratt drainage in the management of lumbar cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Surg Neurol. 2006;65:410-415.

Jankowitz B., Atteberry D.S., Gerszten P.C., et al. Effect of fibrin glue on the prevention of persistent cerebral spinal fluid leakage after incidental durotomy during lumbar spinal surgery. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:1169-1174.

Kitchel S.H., Eismont F.J., Green B.A. Closed subarachnoid drainage for management of cerebrospinal fluid leakage after an operation on the spine. J Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71:984-987.

Mayfield F., Kurokawa K. Watertight closure of spinal dural mater: technical note. J Neurosurg. 1975;43:639-640.

Narotam P.K., Joe S., Nathoo N., et al. Collagen matrix (DuraGen) in dural repair: analysis of a new modified technique. Spine. 2004;29:2861-2869.

Rosenthal J., Hahn J.F., Martinez G.J. A technique for closure of leak of spinal fluid. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:948-950.

Shapiro S.A., Snuder W. Spinal instrumentation with a low complication rate. Surg Neurol. 1997;48:566-574.

Smith M.D., Bolesta M.J., Leventhal M., Bohlman H.H. Postoperative cerebrospinal—fluid fistula associated with erosion of the dura. Findings after anterior resection of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:270-277.

Stolke D., Sollman W.P., Siefert V. Intra and postoperative complications in lumbar disc surgery. Spine. 1989;14:56-59.

Tafazal S.I., Sell P.J. Incidental duratomy in lumbar spine surgery: incidence and management. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:287-290.

Waisman M., Schweppe Y. Postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leakage after lumbar spine operations: conservative treatment. Spine. 1991;16:52-53.

1. Cammisa F.P.Jr., Girardi F.P., Sangani P.K., et al. Incidental durotomy in spine surgery. Spine. 2000;25:2663-2667.

2. Stolke D., Sollman W.P., Siefert V. Intra and postoperative complications in lumbar disc surgery. Spine. 1989;14:56-59.

3. Bosacco S.J., Gardner M.J., Guille J.T. Evaluation and treatment of dural tears in lumbar spine surgery: a review. Clin Orthop. 2001;389:238-247.

4. Smith M.D., Bolesta M.J., Leventhal M., Bohlman H.H. Postoperative cerebrospinal- fluid fistula associated with erosion of the dura. Findings after anterior resection of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74:270-277.

5. Hannallah D., Lee J., Khan M., et al. Cerebrospinal fluid leaks following cervical spine surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90:1101-1105.

6. Shapiro S.A., Snuder W. Spinal instrumentation with a low complication rate. Surg Neurol. 1997;48:566-574.

7. Fountas K.N., Kapsalaki E.Z., Johnston K.W. Cerebrospinal fluid fistula secondary to dural tear in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: case report. Spine. 2005;30:E277-E280.

8. Narotam P.K., Joe S., Nathoo N., et al. Collagen matrix (DuraGen) in dural repair: analysis of a new modified technique. Spine. 2004;29:2861-2869.

9. Tafazal S.I., Sell P.J. Incidental duratomy in lumbar spine surgery: incidence and management. Eur Spine J. 2005;14:287-290.

10. Faraj A.A., Webb J.K. Early complications of spinal pedicle screw. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:324-326.

11. Freidberg S. Surgical management of cerebrospinal fluid leakage after spinal surgery. In: Schmidek H.H., Sweet W.H. Operative Neurosurgical Techniques. 5th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2005:2147-2152.

12. Jankowitz B., Atteberry D.S., Gerszten P.C., et al. Effect of fibrin glue on the prevention of persistent cerebral spinal fluid leakage after incidental durotomy during lumbar spinal surgery. Eur Spine J. 2009;18:1169-1174.

13. Hughes S., Ozqur B.M., German M., Taylor W.R. Prolonged Jackson-Pratt drainage in the management of lumbar cerebrospinal fluid leaks. Surg Neurol. 2006;65:410-415.

14. Waisman M., Schweppe Y. Postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leakage after lumbar spine operations: conservative treatment. Spine. 1991;16:52-53.

15. Rosenthal J., Hahn J.F., Martinez G.J. A technique for closure of leak of spinal fluid. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1975;140:948-950.

16. Kitchel S.H., Eismont F.J., Green B.A. Closed subarachnoid drainage for management of cerebrospinal fluid leakage after an operation on the spine. J Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71:984-987.

17. Mayfield F., Kurokawa K. Watertight closure of spinal dural mater: technical note. J Neurosurg. 1975;43:639-640.