CHAPTER 28 Surgical Hip Dislocation for Femoroacetabular Impingement

Introduction

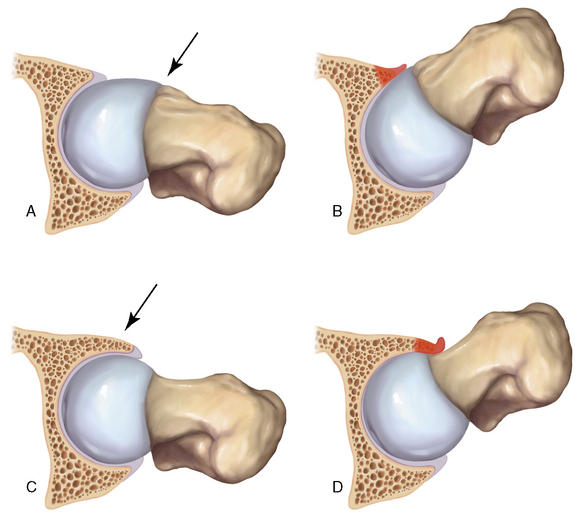

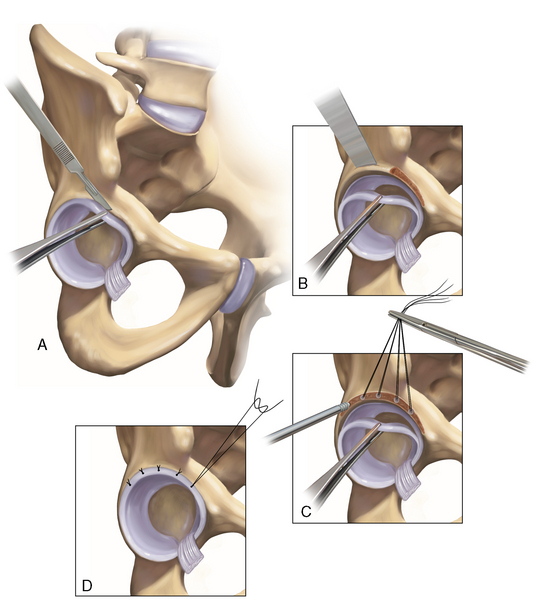

Two distinct mechanisms of FAI have been described; these are commonly referred to as cam disease and pincer disease (Figure 28-1, A through D). The descriptions of these conditions were based on the skeletal morphology and the pattern of chondrolabral damage observed during surgical hip dislocations. However, these morphologic patterns are not mutually exclusive; it is quite common for patients to have components of both cam and pincer types of impingements. With cam FAI, there is an abnormal bony prominence at the femoral head–neck junction that is often located anterosuperiorly. During hip flexion, the abnormal contoured femoral head engages the anterosuperior acetabulum and produces shear forces that lead to chondral abrasion, delamination, and, eventually, full-thickness cartilage loss. The natural history of this impingement process is initially acetabular cartilage injury, which is followed by labral injury and ultimately joint arthrosis. At first the labrum is uninvolved, but, with further impingement, labral injury results from the further loosening of the labrum at the transition zone between the peripheral cartilage and the labrum itself. With pincer FAI, there is increased acetabular coverage that leads to linear contact between the femoral head–neck junction and the acetabular rim. Acetabular overcoverage may be either generalized, as in coxa profunda and protrusio acetabuli, or localized, as in acetabular retroversion and anterior acetabular overhang. Unlike what occurs with cam FAI, the labrum is the first to get injured with intrasubstance degeneration, cyst formation, and bone apposition at the rim, which further deepens the socket and exacerbates the problem. The prominent acetabular rim abuts with the femoral neck and causes the femoral head to lever in the acetabulum. This chronic levering of the head generates shear forces and injury to the posterior cartilage. Over time, this contrecoup mechanism leads to posteroinferior chondral damage and joint space narrowing.

Treatment, indications, and contraindications

The most important indications for FAI surgery are physical examination and radiographic findings that are consistent with FAI (Box 28-1). Proper imaging studies are critical to confirm and quantify the deformity and to assess the degree of arthritis. Unnecessary treatment delays also should be avoided.

History and physical examination

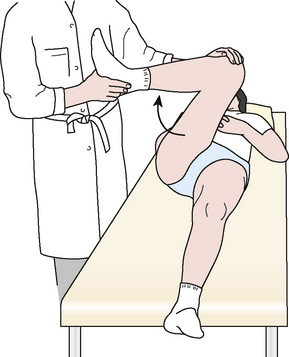

It is crucial that all FAI patients receive a thorough physical examination, because there are many extra-articular diagnoses that can present with hip pain. The examination begins with detailed motor and sensory examinations. Next, the range of motion is assessed. Limited internal rotation of the flexed and adducted hip is seen in both cam and pincer FAI, but a greater loss of internal rotation is seen with cam FAI. This is followed by FAI-specific tests. An impingement test (Figure 28-2) is performed with the patient in the supine position; the affected hip is adducted and internally rotated as it is passively flexed. In patients with FAI, the femoral head–neck junction and the acetabulum abut, thus producing shear forces on the labrum and reproducing a sharp pain in the groin. A posteroinferior FAI test is performed with the patient supine on the edge of the examination table with the legs dangling free from the end. The examiner then extends and externally rotates the affected hip. Deep-seated groin pain during this maneuver is indicative of posteroinferior FAI, and it is frequently combined with limited external rotation. Finally, other critical examination maneuvers are performed to find associated pathology of the psoas, the iliotibial band, the lower back, and other related structures.

Imaging

After the adequacy of the radiograph has been verified, it should be reviewed in a systematic fashion. First, the radiograph should be assessed for the coverage of the femoral head (i.e., center edge angle and Tönnis angle) or for gross arthritic changes (i.e., Tönnis scale). Next, the acetabulum should be inspected for pincer-type FAI. Five radiographic structures must be identified: 1) the medial acetabular wall; 2) the ilioischial line; 3) the anterior wall of the acetabulum; 4) the posterior wall of the acetabulum; and 5) the femoral head. By understanding the relationship of these radiographic structures, all of the common causes of pincer FAI can be diagnosed. In a patient with coxa profunda, the medial acetabular wall approaches and overlaps (if it does not pass medial to) the ilioischial line, which causes a deep socket. In a patient with protrusio, the femoral head is medial to the ilioischial line. In a patient with true acetabular retroversion, the anterior and posterior acetabular walls overlap; they also have a positive crossover sign and a prominent ischial spine (Figure 28-3, A). In these cases, there may or may not be a sufficient posterior wall, but there is always a relative anterior overhang. Finally, one must assess for os acetabuli, which can represent either broken pincer lesions or unfused portions of the acetabulum (i.e., true os acetabuli).

On the femoral side, cam FAI is readily diagnosed with the proper radiographs. Given its mostly anterosuperior location, the cam lesion is often underappreciated on a standard anteroposterior radiograph, and it may be obstructed by the greater trochanter on a frog-leg lateral view. The aspheric head–neck junction is best visualized with either a 45-degree Dunn view or a cross-table lateral view with the leg in 15 degrees of internal rotation. The Dunn view, which is also known as an extended neck lateral view, is taken with the patient’s hip in neutral rotation, flexed 45 degrees, and abducted 20 degrees. The internally rotated cross-table lateral view is often more practical for routine use, because positioning the patients for the Dunn view requires a leg holder or an assistant. Either image can be used to measure the head–neck offset and the alpha angle, both of which are abnormal parameters that can be used to assess cam FAI (see Figure 28-3, B). In addition, the femoral neck shaft angle should also be assessed for any significant varus deformities.

In addition to radiographs, we routinely obtain a magnetic resonance arthrogram to accurately assess chondral delamination and full-thickness cartilage defects. In many cases of FAI, hips that produce normal radiographs (as defined by Tönnis grade) in fact have extensive chondral injury. Magnetic resonance imaging also assesses for labral pathology or subtle signs of FAI, such as fibrocystic changes at the head–neck junction; these changes are also known as synovial herniation pits. The magnetic resonance imaging should involve the use of cartilage-specific sequences, and it should be performed in radial-directed sections for the accurate measurement of angulation and the translation of the impingement lesions in the radiologic reference planes (Figure 28-4). Standard magnetic resonance imaging of the pelvis is often less sensitive, because it does not occur in the correct sequence plane with a resolution being far too low. In addition, although computed tomography scans provide a superior assessment of femoral anteversion, acetabular version, and femoral offset, they require radiation exposure during 20 radiologic pelvic overviews; thus, computed tomography should be used quite judiciously. Other advantages of obtaining a magnetic resonance image include the evaluation of stress fractures and soft-tissue abnormalities as well as the measurement of the alpha angle and acetabular version.

Surgical technique

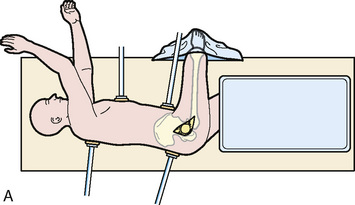

General or spinal anesthesia is used. The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position in well-padded bolsters, and care is taken to also protect the nonoperated limb. Correct orientation is important to allow for the accurate assessment of acetabular orientation during the procedure. The skin is cleansed with a standard preparation solution over the trochanteric region. The patient is prepared and draped in standard sterile fashion (Figure 28-5, A) with a free leg sterile bag drape placed on the opposite side of the operating table to receive the lower leg during hip dislocation (see Figure 28-5, B). A second-generation cephalosporin antibiotic is given for prophylaxis and continued for 24 hours. Image intensifying and laser Doppler flowmetry are not routinely used, but both can be helpful for either osteotomy fixation or to monitor the perfusion of the femoral head.

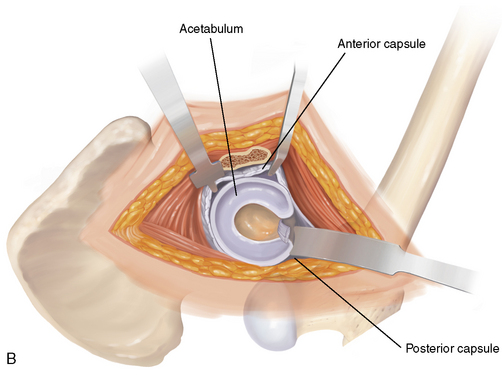

If pincer FAI is noted preoperatively and confirmed intraoperatively, then an acetabular rim trimming is performed (Figure 28-6, A through D). First, the labrum must be detached from the acetabular rim with the use of sharp dissection. Because the typical location of acetabular rim lesions is the anterosuperior margin, the excessive rim segment can be removed with a curved osteotome. The amount of rim resected depends on the location of the crossover sign and the femoral head coverage (e.g., the value of the lateral center-edge angle, femoral head extrusion) seen on the preoperative plain radiograph. Ultimately, however, intraoperative tests are performed to assess the degree of overcoverage. These tests are performed after both the acetabular and femoral resections, if needed. Rim excision is performed until no impingement exists but not at the expense of creating instability or dysplasia. If there are full-thickness chondral lesions, then a microfracture is performed with angled awls. The labrum is then reattached with the use of two to four small bone anchors placed into the bed of bleeding cancellous bone approximately 10 mm to 15 mm apart. The nonabsorbable suture of the anchor should be passed through the base of the labrum and tied with the labrum firmly seated against the acetabular bone so that the knot lies on the nonarticular surface of the labrum.

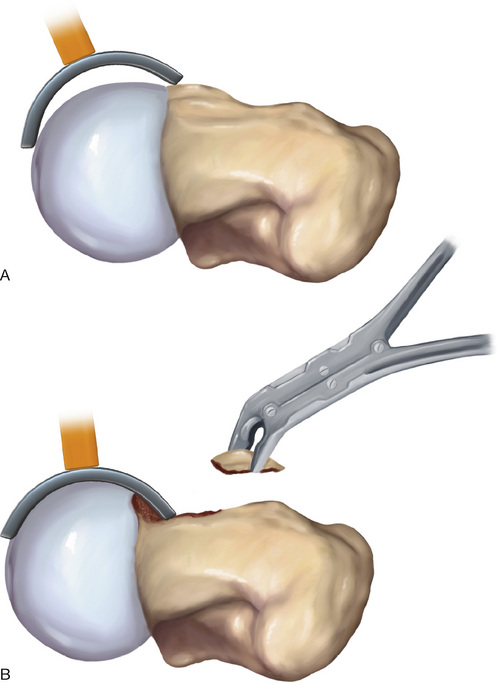

The most common location for this pathology is the anterosuperior head–neck junction, with the abnormal cartilage having a slightly hypervascular, pink appearance. The presence of a cyst near the peripheral border of the nonspheric segment is sometimes noted, which indicates the point of maximum impingement. The abnormal bone can be removed carefully with the use of curved chisels until a normal head–neck offset is recreated, with great care taken not to laterally injure the terminal branches of the MFCA in the posterosuperior retinaculum (Figure 28-7, A and B). Unfortunately, this area may also be nonspheric, in which case the debridement should start proximally on the neck and reach the point at which the vessels enter their intraosseous course. A periosteal elevator may also be used to strip a portion of the retinaculum off of the bone as well. Femoral resection should be performed cautiously with regular reassessment with the use of the spheric templates to avoid over-resection, which both increases the risk of femoral neck fracture (only with excessive resections) and endangers the loss of the labrum’s suction seal effect with the femoral head.

Capsular closure is performed without excessive tension to avoid the compression of the retinacular vessels. The trochanteric fragment is reduced anatomically according to the triplanar osteotomy step cuts, and it is reattached with the use of 3.5-mm or 4.5-mm screws. With the triplanar trochanteric osteotomy, 3.5-mm screws are sufficient for fixation, but if the patient develops any reactive bursitis, these screws are slightly more difficult to remove. Alternatively, 4.5-mm screws are much easier to remove if the patient becomes symptomatic. The fascia lata and the fat and cutaneous layers are then carefully closed in a layered fashion. Drains are rarely indicated. Box 28-2 reviews technical pearls for this procedure.

Rehabilitation and postoperative management

A postoperative radiograph is obtained in the recovery department (Figure 28-8). The patient is usually immobilized postoperatively on crutches, with toe-touch weight bearing for 6 weeks for triplanar osteotomy or 8 weeks for classic slide osteotomy. The patient is prohibited from performing hip flexion of more than 70 degrees (or of more than 90 degrees after a triplanar procedure) and from actively abducting or adducting the hip to allow for the proper healing of the osteotomy site. Continuous passive motion with flexion limited to 70 degrees is started on postoperative day 1 and continued until discharge to prevent the formation of intra-articular adhesions between the femoral osteochondroplasty and the capsule. If a microfracture was performed, then the use of continuous passive motion is extended for up to 8 weeks. The patient is usually discharged after 5 days. All patients receive low-molecular-weight heparin until full mobilization occurs.

Results

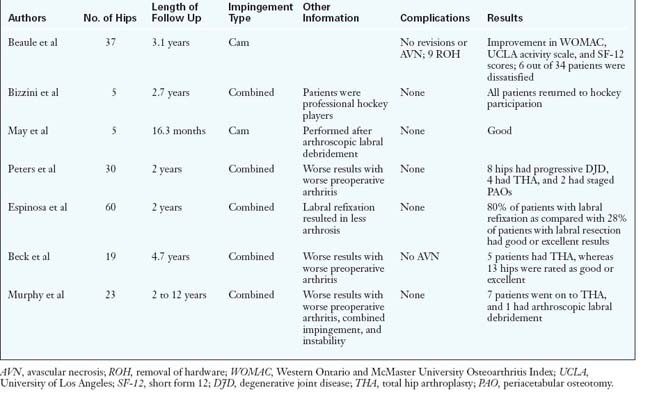

A review of the literature and of the results of open impingement surgery is given in Table 28-1. To date, there have been seven series with approximately 199 patients. The patient’s prognosis generally depends on the extent of articular damage. Stated another way, the extent of preoperative arthritis is an important predictor of outcome. In addition, it has been shown that labral refixation appears to yield better clinical and radiographic results, whereas cases that involve both impingement and instability have been shown to have worse results.

Beaule P.E., Le Duff M.J., Zaragoza E. Quality of life following femoral head-neck osteochondroplasty for femoroacetabular impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):773-779.

Beck M., Kalhor M., Leunig M., Ganz R. Hip morphology influences the pattern of damage to the acetabular cartilage: femoroacetabular impingement as a cause of early osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(7):1012-1018.

Beck M., Leunig M., Parvizi J., Boutier V., Wyss D., Ganz R. Anterior femoroacetabular impingement: part II. Midterm results of surgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res (418); 2004:67-73.

Bizzini M., Notzli H.P., Maffiuletti N.A. Femoroacetabular impingement in professional ice hockey players: a case series of 5 athletes after open surgical decompression of the hip. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(11):1955-1959.

Espinosa N., Beck M., Rothenfluh D.A., Ganz R., Leunig M. Treatment of femoro-acetabular impingement: preliminary results of labral refixation. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(suppl 2):36-53. Pt.1

A review of the open surgical technique for femoroacetabular impingement with labral refixation..

Espinosa N., Rothenfluh D.A., Beck M., Ganz R., Leunig M. Treatment of femoro-acetabular impingement: preliminary results of labral refixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(5):925-935.

Ganz R., Gill T.J., Gautier E., Ganz K., Krugel N., Berlemann U. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip: a technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2001;83B(8):1119-1124.

Ganz R., Leunig M., Leunig-Ganz K., Harris W.H. The etiology of osteoarthritis of the hip: an integrated mechanical concept. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(2):264-272.

Ganz R., Parvizi J., Beck M., Leunig M., Notzli H., Siebenrock K.A. Femoroacetabular impingement: a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res (417); 2003:112-120.

Gautier E., Ganz K., Krugel N., Gill T., Ganz R. Anatomy of the medial femoral circumflex artery and its surgical implications. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(5):679-683.

Gibson A. Posterior exposure of the hip joint. J Bone Joint Surg. 1950;32B:183-186.

Guevara C.J., Pietrobon R., Carothers J.T., Olson S.A., Vail T.P. Comprehensive morphologic evaluation of the hip in patients with symptomatic labral tear. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;453:277-285.

Jamali A.A., Mladenov K., Meyer D.C., Martinez A., Beck M., Ganz R., Leunig M. Anteroposterior pelvic radiographs to assess acetabular retroversion: high validity of the “cross-over sign.”. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(6):758-765.

Kalberer F., Sierra R., Madan S., Ganz R., Leunig M. Ischial spine projection into the pelvis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:677-683.

Leunig M., Podeszwa D., Beck M., Werlen S., Ganz R. Magnetic resonance arthrography of labral disorders in hips with dysplasia and impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res (418); 2004:74-80.

Locher S., Werlen S., Leunig M., Ganz R. [MR-Arthrography with radial sequences for visualization of early hip pathology not visible on plain radiographs]. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 2002;140(1):52-57.

A description of a successful technique to improve MRI visualization of the hip..

Mardones R.M., Gonzalez C., Chen Q., Zobitz M., Kaufman K.R., Trousdale R.T. Surgical treatment of femoroacetabular impingement: evaluation of the effect of the size of the resection. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(2):273-279.

May O., Matar W.Y., Beaule P.E. Treatment of failed arthroscopic acetabular labral debridement by femoral chondro-osteoplasty: a case series of five patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(5):595-598.

McCarthy J.C., Noble P.C., Schuck M.R., Wright J., Lee J. The Otto E. Aufranc Award: the role of labral lesions to development of early degenerative hip disease. Clin Orthop. 2001;393:25-37.

Mercati E., Guary A., Myquel C., Bourgeon A. [A postero-external approach to the hip joint. Value of the formation of a digastric muscle]. J Chir (Paris). 1972;103(5):499-504.

Meyer D.C., Beck M., Ellis T., Ganz R., Leunig M. Comparison of six radiographic projections to assess femoral head/neck asphericity. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;445:181-185.

Murphy S., Tannast M., Kim Y-J., Buly R., Millis M. Debridement of the adult hip for femoroacetabular impingement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;429:178-181.

Murray R.O. The aetiology of primary osteoarthritis of the hip. Br J Radiol. 1965;38(455):810-824.

Classical description of pistol grip deformity and early arthritis..

Notzli H.P., Wyss T.F., Stoecklin C.H., Schmid M.R., Treiber K., Hodler J. The contour of the femoral head-neck junction as a predictor for the risk of anterior impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84(4):556-560.

Parvizi J., Leunig M., Ganz R. Femoroacetabular impingement. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2007;15(9):561-570.

Pauwels F. Biomechanics of the Normal and Diseased Hip: Theoretical Foundation, Technique and Results of Treatment. Berlin, Germany: Springer-Verlag, 1976. An Atlas. Edited

Classic biomechanical description of hip biomechanics and osteotomies..

Peters C.L., Erickson J.A. Treatment of femoro-acetabular impingement with surgical dislocation and debridement in young adults. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1735-1741.

Clinical study of open surgical treatment of FAI at 2 years of follow up using HHS..

Reynolds D., Lucas J., Klaue K. Retroversion of the acetabulum. A cause of hip pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(2):281-288.

Robertson W.J., Kadrmas W.R., Kelly B.T. Arthroscopic management of labral tears in the hip: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2007;455:88-92.

Seldes R.M., Tan V., Hunt J., Katz M., Winiarsky R., Fitzgerald R.H.Jr Anatomy, histologic features, and vascularity of the adult acetabular labrum. Clin Orthop (382); 2001:232-240.

Siebenrock K.A., Kalbermatten D.F., Ganz R. Effect of pelvic tilt on acetabular retroversion: a study of pelves from cadavers. Clin Orthop Relat Res (407); 2003:241-248.

Siebenrock K.A., Schoeniger R., Ganz R. Anterior femoro-acetabular impingement due to acetabular retroversion. Treatment with periacetabular osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(2):278-286.

Sussmann P.S., Ranawat A.S., Lipman J., Lorich D.G., Padgett D.E., Kelly B.T. Arthroscopic versus open osteoplasty of the head-neck junction: a cadaveric investigation. Arthroscopy. 2007;23(12):1257-1264.

Tannast M., Siebenrock K.A., Anderson S.E. Femoroacetabular impingement: radiographic diagnosis—what the radiologist should know. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(6):1540-1552.

Tonnis D., Heinecke A. Acetabular and femoral anteversion: relationship with osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(12):1747-1770.

Wenger D.E., Kendell K.R., Miner M.R., Trousdale R.T. Acetabular labral tears rarely occur in the absence of bony abnormalities. Clin Orthop Relat Res (426); 2004:145-150.