Chapter 7 Surgical Anatomy of the Abdomen and Pelvis

ANTERIOR ABDOMINAL WALL

The abdominal wall is made up of four structural layers beneath the skin: (1) subcutaneous tissue and superficial fascial layers, (2) muscles and transversalis fascia, (3) deep fascia of the rectus sheath and the extraperitoneal fascia, and (4) parietal peritoneum (Fig. 7-1). Interspersed among these layers are several important nerves and blood vessels.

Deep Fascia of the Rectus Sheath and Extraperitoneal Fascia

The inguinal canal is about 4 cm long and runs parallel to the inguinal ligament. The inguinal canal has an anterior wall formed by the aponeurosis of the external oblique, an inferior wall formed by the inguinal ligament, a superior wall formed by arching fibers of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis muscles, and a posterior wall formed by the transversalis fascia. A defect, or more precisely a tubular evagination, of the transversalis fascia forms the deep inguinal ring, through which the round ligament enters the inguinal canal. This ring lies midway between the anterior superior iliac spine and the pubic symphysis. Medial to the deep inguinal ring are the inferior epigastric vessels. The opening of the aponeurosis of the external oblique superior to the pubic tubercle is the superficial inguinal ring. Through it the round ligament, the terminal part of the ilioinguinal nerve, and the genital branch of the genitofemoral nerve exit the inguinal canal (see Fig. 7-1).

Nerves

These nerves are particularly at risk in lower abdominal incisions, which are the most common causes of abdominal wall pain as a result of nerve entrapment by suture or scar tissue.1 For this reason, knowledge of the course of the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves in the anterior abdominal wall can help avoid injury during laparotomy and laparoscopic surgery. Data from cadaveric studies suggest that injury to these nerves can be minimized during laparoscopy by making transverse skin incisions and placing laparoscopic trocars at or above the level of the anterior superior iliac spine.2 In cases of chronic abdominal pain caused by these nerves, an injection of local anesthetic at a site approximately 3 cm medial to the anterior superior iliac spine will often provide relief.

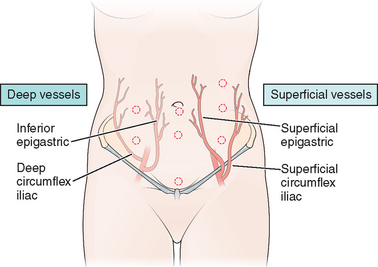

Blood Vessels

The major vessels in the anterior abdominal wall can be divided into deep and superficial vessels (Fig. 7-2).3 The superficial vessels include the superficial epigastric and the superficial circumflex iliac vessels. These vessels are branches of the femoral artery and vein. They course bilaterally through the subcutaneous tissue of the abdominal wall, branching as they proceed toward the head of the patient.

Figure 7-2 Anterior abdominal wall blood vessels.

(Modified from Hurd WW, Bude RO, DeLancey JOL, Newman JS: The location of abdominal wall blood vessels in relationship to abdominal landmarks apparent at laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol 171:642–646, 1994.)

To avoid vessel injuries, these superficial vessels can often be seen before secondary laparscopic port placement by transillumination of the abdominal wall using the intra-abdominal laparoscopic light source.3 Injury to these vessels during trocar placement can result in a palpable hematoma that will be found to be located anterior to the fascia on computed tomography (CT) scan.4 In unusual cases, the hematoma can dissect down into the labia majora.

The course of the inferior epigastric vessels can often be visualized at laparoscopy as the lateral umbilical fold because of the absence of the posterior rectus sheath below the arcuate line (Fig. 7-3).5 Injury to these vessels can result in life-threatening hemorrhage that must be quickly controlled by occluding the lacerated vessels with electrosurgery or precisely placed sutures.

If these vessels cannot be visualized (usually because of excess tissue), trocars should be place approximately 8 cm lateral to the midline and 8 cm above the pubic symphysis.3 On the right side of the abdomen, this point approximates McBurney’s point, located one-third the distance from the anterior superior iliac spine to the umbilicus. The corresponding point on left is sometimes referred to as Hurd’s point.

Peritoneal Landmarks

Peritoneal Folds

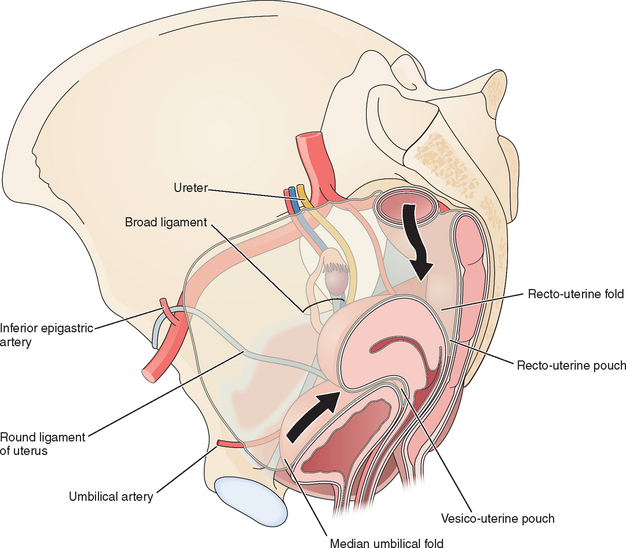

Several useful landmarks can be used to guide the laparoscopic surgeon to avoid injury to important retroperitoneal structures. Two midline and two bilateral pairs of peritoneal folds can usually be seen on the anterior abdominal wall at laparoscopy (Fig. 7-4). The falciform ligament, which is the remnant of the ventral mesentery and contains the obliterated umbilical vein in its free edge, can be seen in the midline above the umbilicus extending to the liver. The median umbilical fold, which contains the urachus, can usually be seen in the midline below the umbilicus extending to the bladder. Although the urachus normally closes before birth, it should be avoided during secondary trocar placement, both because it can be difficult to penetrate and in rare cases can remain patent to the bladder.

On each side of the urachus lie the medial umbilical folds. These landmarks contain the obliterated umbilical arteries and extend from the umbilicus to the anterior division of the internal iliac artery. Lateral to these, the lateral umbilical folds can be seen in 82% of patients.5 These are the most important structures to the laparoscopist, because they contain the inferior epigastric vessels and knowing their location can help the laparoscopist avoid injury to these large vessels during placement of secondary laparoscopic ports.

Peritoneal pouches normally exist between the pelvic organs (see Fig. 7-4). The vesico-uterine pouch is located anteriorly between the uterus and bladder. The ventral margin of the bladder can be visualized in approximately half of patients behind the anterior abdominal wall peritoneum and is important for secondary trocar placement, especially after previous abdominal surgery.5 The dorsal bladder margin can often be visualized on the anterior uterus and is used as a landmark during dissections during hysterectomy.

UPPER ABDOMEN

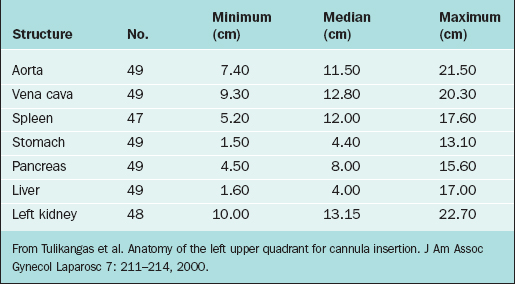

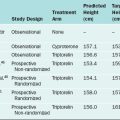

For the left upper quadrant technique, the Verres needle and primary trocar are placed into the abdomen 2 cm below the subcostal arch at the midclavicular line. It is important to know what anatomic structures lie close to this area to avoid injury during insertion of the primary cannula. The anatomic structures at risk of injury in this area include (from posterior to anterior) the spleen, splenic flexure of the colon, stomach, and left lobe of the liver. Although relatively few series using the left upper quadrant approach have been reported, it appears that the colon might be the organ at greatest risk of injury using this technique.6 Table 7-1 lists the common body structures and distances from the left upper quadrant point from CT scan data.7

POSTERIOR ABDOMINAL WALL AND PELVIC SIDEWALLS

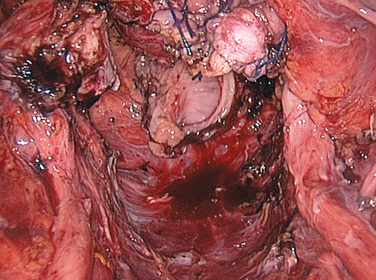

Structures of the posterior abdominal wall anterior to the vertebral column and the pelvic sidewalls are of interest to the reproductive surgeon for several diverse reasons. First, retroperitoneal dissection can be required in these areas during some gynecologic procedures, such as treatment of deep endometriosis and removal of pelvic masses adherent to the peritoneum. Secondly, an understanding of the course of retroperitoneal nerves is a useful reminder to the surgeon to be aware of the position of self-retaining retractor blades during laparotomy, because permanent nerve injury can result from prolonged pressure on these structures. Finally, with the use of closed techniques for primary laparoscopic trocar placement, injury to the retroperitoneal structures can occur, and knowledge of this anatomy is essential for effective and expedient management.

Nerves

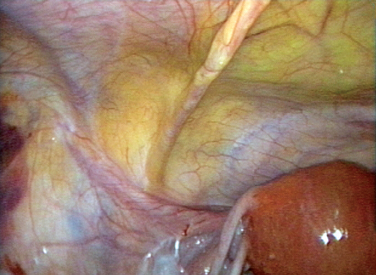

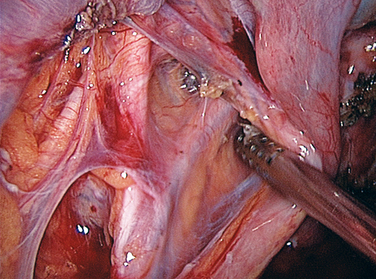

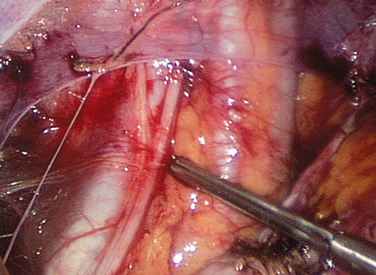

Multiple nerves enter or transverse the pelvic sidewalls. Deep nerves of the pelvis, such as the superior and inferior gluteal nerves, supply several of the pelvic muscles but are not visible during reproductive surgery. Likewise, the obturator nerve traverses the pelvis. The obturator nerve originates at spinal cord levels L2–L4 and descends in the psoas major muscle until the pelvic brim, when it emerges medially to lie on the obturator internus muscle lateral to the internal iliac artery and its branches (Figs. 7-5 and 7-6). It descends on the obturator internus muscle to enter the obturator canal and exits in the thigh. It is sensory to the medial side of the thigh and motor to the muscles in the medial compartment of the thigh (the adductor muscles). It can easily be seen during pelvic sidewall dissections for endometriosis or lymph node dissection.

The genitofemoral nerve (from spinal cord levels L1 and L2) lies on the anterior surface of the psoas muscle (Fig. 7-7). It has two branches, the femoral and genital. The femoral branch enters the thigh under the inguinal ligament, and the genital branch enters the inguinal canal. The genitofemoral nerve is sensory to the skin over the anterior surface of the thigh. Injury to this nerve is seen after appendectomy or when the fold of peritoneum from the sigmoid colon to the psoas muscle is incised.

Blood Vessels

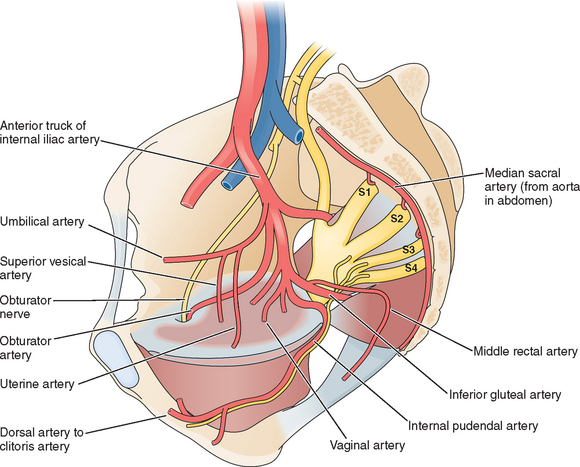

The major blood vessels are perhaps the most important structures of the pelvis (see Fig. 7-5). Successful pelvic surgery requires a thorough understanding of their anatomy. The aorta bifurcates at the level of L4 into the left and right common iliac arteries. The common iliac artery passes laterally, anterior to the common iliac vein to the pelvic brim. At the lower border of L5, the common iliac artery divides into internal and external iliac branches. The external iliac artery gives off only two branches, the inferior epigastric artery and the deep circumflex iliac artery, and then, after passing under the inguinal ligament, becomes the femoral artery, which is the primary blood supply to the lower limb.

The internal iliac artery supplies all of the organs within the pelvis and sends branches out through the greater sciatic foramen to supply the gluteal muscles. A branch also exists through the greater sciatic foramen and re-enters the lesser sciatic foramen to supply the perineum. After passing over the pelvic brim, the internal iliac arteries divide into anterior and posterior trunks. The posterior trunk consists of three branches: the ilolumbar artery, the lateral sacral artery, and the superior gluteal artery. These vessels are closely related to the nerve plexus on the piriformis muscle. The superior gluteal artery is the largest branch of the internal iliac artery and supplies the muscles and skin of the gluteal region. Accidental occlusion of this artery during uterine fibroid embolization can result in necrosis of the gluteal region.

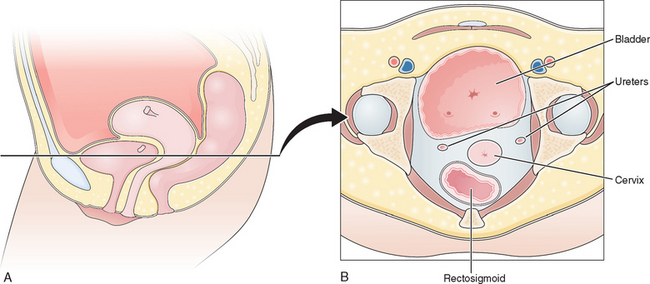

Ureters

The average distance between the ureters and cervix is greater than 2 cm.8 However, the reproductive surgeon should remember that this distance can be less than 0.5 cm in approximately 10% of women, which explains in part the relatively common occurrence of ureteral injury during hysterectomy (Fig. 7-8).

MUSCLES OF THE PELVIC FLOOR

Pelvic Diaphragm

The pelvic diaphragm forms the muscular floor of the pelvis and is made up of the levator ani and coccygeus muscles that are all attached to the inner surface of the minor pelvis (Fig. 7-9).9 The levator ani is composed of three muscles. The innermost puborectalis muscle is attached to the pubic symphysis and encircles the rectum. The thicker, more medial pubococcygeus muscle runs from the pubic symphysis to the coccyx. This muscle is attached laterally to the obturator internus muscle by a thickened band of dense connective tissue called the arcus tendineus. The fusion of these bilateral muscles in the midline is called the levator plate and forms a shelf on which the pelvic organs rest. When the body is in a standing position, the levator plate is horizontal and supports the rectum and upper two thirds of the vagina above it. The thinner, more lateral iliococcygeus muscle runs from the arcus tendineus and ischial spine to the coccyx. The posterolateral margin of the pelvic diaphragm is the coccygeus muscle, which extends from the ischial spine to the coccyx and lower sacrum.

Weakness or damage to parts of the pelvic diaphragm may loosen the sling behind the anorectum and cause the levator plate to sag. Women with prolapse have been shown to have an enlarged urogenital hiatus on clinical examination.10

PELVIC VISCERA

Vagina

The vagina is a musculomembranous sheath 7 to 9 cm in length that extends anteroinferiorly from the uterine cervix to the vestibule. Because the cervix enters the vagina along the anterior wall, the posterior wall is about 1 cm longer than the anterior wall. Anterior and posterior to the cervix are vaginal fornices. Intraperitoneally, the vagina is separated from the rectum by the rectouterine pouch and from the bladder by the vesicouterine pouch (see Fig. 7-4).

Uterine Tubes

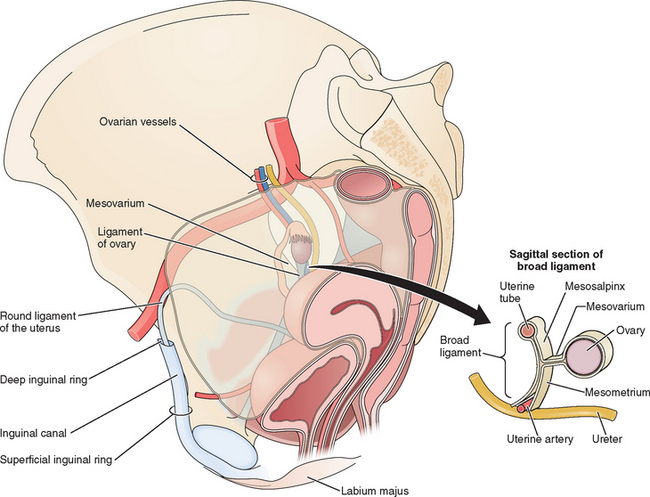

The uterine tubes are contained within the uppermost margin of the broad ligament and measure about 10 to 12 cm (see Fig. 7-1). Each tube is divided into several distinct anatomic segments: intramural (or interstitial), isthmic, ampullary, and infundibulum. The internal diameter of the tube ranges from less than 1 mm at the intramural portion to up to 10 mm at the infundibulum.

Ovaries

The ovaries are ovoid structures suspended from the posterior aspect of the broad ligament by the mesovarium (see Fig. 7-1). This fold of peritoneum contains an extensive complex of blood vessels. The infundibulopelvic ligament (suspensory ligament of the ovary) enters the ovary along its superior pole and carries the ovarian vessels, lymphatics, and nerves. These vessels are in close proximity to the ureter at the pelvic brim (see Fig. 7-1). The ovarian ligament is located on the inferior pole of the ovary. The ovary is attached to the broad ligament by the mesovarium. It has a rich vascular supply. An arcade of vessels is formed from the anastomoses of the uterine and ovarian vessels. Theses vessels, called helicine because of their highly coiled structure, course through the mesovarium into the medulla. Veins then drain the medulla from a plexus seen in the mesovarium. Dissection around this area during a lysis of tubal adhesions or cystectomy should be performed with great care to avoid bleeding.

PELVIC FASCIAS AND LIGAMENTS

Peritoneal Folds

The broad ligament is a double-layered transverse fold of peritoneum that encloses the uterus and uterine tubes and extends to the lateral walls and pelvic floor (see Figs. 7-1 and 7-4). It is made up of the mesometrium lateral to the uterus that encloses the uterine vessels and the ureters, the mesovarium that attaches the ovary to the broad ligament posteriorly, and the mesosalpinx that connects the uterine tube near the base of the mesovarium.

1 Stultz P. Peripheral nerve injuries resulting from common surgical procedures in the lower abdomen. Arch Surg. 1982;117:324-327.

2 Whiteside J, Barber M, Walters M, Falcone T. Anatomy of ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves in relation to trocar placement and low transverse incisions. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1574-1578.

3 Hurd WW, Bude RO, DeLancey JOL, Newman JS. The location of abdominal wall blood vessels in relationship to abdominal landmarks apparent at laparoscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;171:642-646.

4 Hurd WW, Pearl ML, DeLancey JO, Quint EH, et al. Laparoscopic injury of abdominal wall blood vessels: A report of three cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;82:673-676.

5 Hurd WW, Amesse LS, Gruber JS, et al. Visualization of the epigastric vessels and bladder before laparoscopic trocar placement. Fertil Steril. 2003;80:209-212.

6 Patsner B. Laparoscopy using the left upper quadrant approach. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 1999;6:323-325.

7 Tulikangas PK, Nicklas A, Falcone T, Price LL. Anatomy of the left upper quadrant for cannula insertion. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2000;7:211-214.

8 Hurd WW, Chee SS, Gallagher KL, et al. Location of the ureters in relation to the uterine cervix by computed tomography. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:336-339.

9 Herschorn S. Female pelvic floor anatomy: The pelvic floor, supporting structures, and pelvic organs. Rev Urol. 2004;6(Suppl 5):S2-S10.

10 Delancey JO, Hurd WW. Size of the urogenital hiatus in the levator ani muscles in normal women and women with pelvic organ prolapse. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;91:364-368.