CHAPTER 1 Surgical anatomy

Introduction

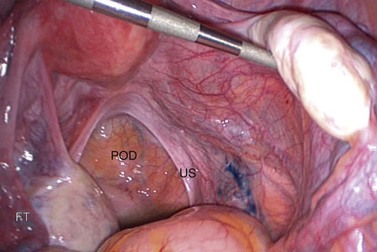

A clear understanding of the anatomy of the female pelvis is essential to successful gynaecological surgery and the avoidance of surgical morbidity. The close relationships between the reproductive, urinary and gastrointestinal tracts must be appreciated, together with the pelvic musculofascial support, vascular and lymphatic circulations, and neurological innervation. It is important to understand the effect of pneumoperitoneum on the anatomy and relationships of the pelvis, and the opportunities afforded by a retroperitoneal approach in minimal access techniques. Figure 1.1 shows a panoramic view of the pelvis from the umbilicus during a laparoscopy. The probe is lifting the right ovary, displaying the right pelvic side wall and ureter (arrows).

The Ovary

Structure

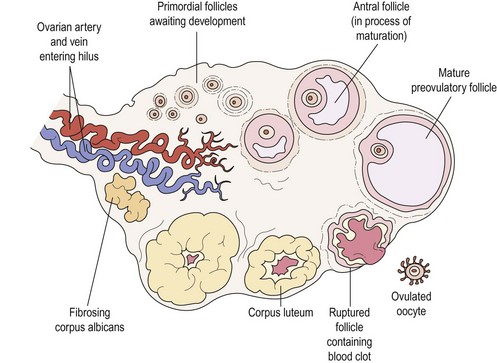

The ovary has a central vascular medulla, consisting of loose connective tissue containing many elastin fibres and non-striated muscle cells, and an outer thicker cortex, denser than the medulla and consisting of networks of reticular fibres and fusiform cells, although there is no clear-cut demarcation between the two. The surface of the ovary is covered by a single layer of cuboidal cells, the germinal epithelium. Beneath this is an ill-defined layer of condensed connective tissue, the tunica albuginea, which increases in density with age. At birth, numerous primordial follicles are found, mainly in the cortex but some in the medulla. With puberty, some form each month into Graafian follicles which, at later stages of their development, form corpora lutea and ultimately atretic follicles, the corpora albicantes (Figure 1.2).

Blood supply

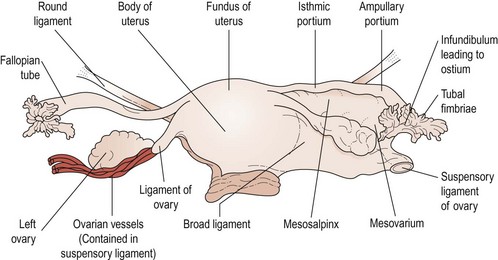

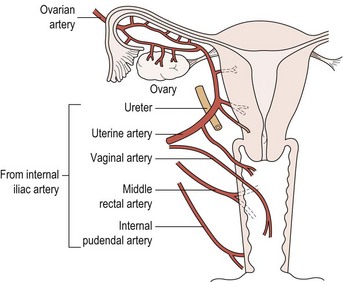

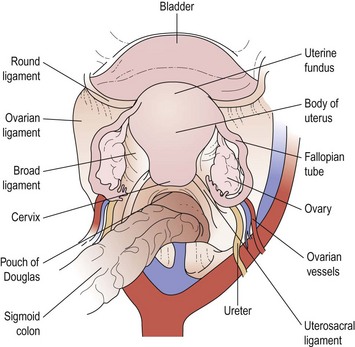

The main vascular supply to the ovaries is the ovarian artery, which arises from the anterolateral aspect of the aorta just below the origin of the renal arteries. The right artery crosses the anterior surface of the vena cava, the lower part of the abdominal ureter and then, lateral to the ureter, enters the pelvis via the infundibulopelvic ligament. The left artery crosses the ureter almost immediately after its origin and then travels lateral to it, crossing the bifurcation of the common iliac artery at the pelvic brim to enter the infundibulopelvic ligament. Both arteries then divide to send branches to the ovaries through the mesovarium. Small branches pass to the ureter and the fallopian tube, and one branch passes to the cornu of the uterus where it freely anastomoses with branches of the uterine artery to produce a continuous arterial arch (see Figure 1.3).

The Uterus

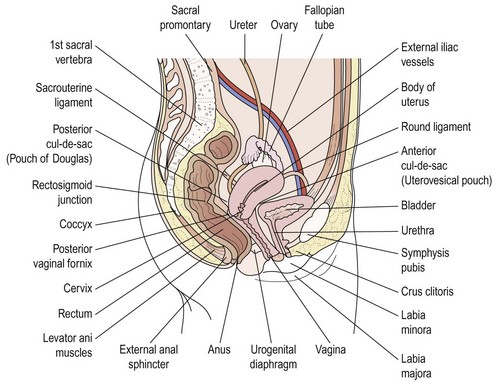

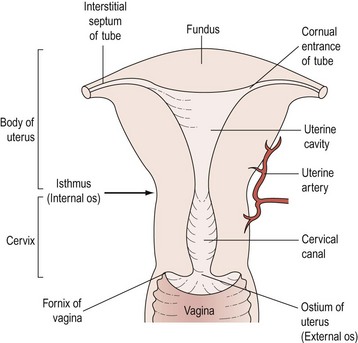

The uterus is shaped like an inverted pear, tapering inferiorly to the cervix and, in the non-pregnant state, is situated entirely within the lesser pelvis. It is hollow and has thick muscular walls. Its maximal external dimensions are approximately 9 cm long, 6 cm wide and 4 cm thick. The upper expanded part of the uterus is termed the ‘body’ or ‘corpus’. The area of insertion of each fallopian tube is termed the ‘cornu’ and that part of the body above the cornu, the ‘fundus’. The uterus tapers to a small central constricted area, the isthmus, and below this is the cervix, which projects obliquely into the vagina and can be divided into vaginal and supravaginal portions (Figure 1.4).

The cavity of the uterus has the shape of an inverted triangle when sectioned coronally; the fallopian tubes open at the upper lateral angles (Figure 1.5). The lumen is apposed anteroposteriorly. The constriction at the isthmus where the corpus joins the cervix is the anatomical internal os.

Figure 1.5 Sectional diagram showing the interior divisions of the uterus and its continuity with the vagina.

The Vagina

The Vulva

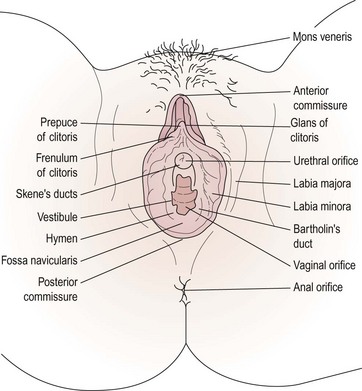

The female external genitalia, commonly referred to as the ‘vulva’, include the mons pubis, the labia majora and minora, the vestibule, the clitoris and the greater vestibular glands (Figure 1.6).

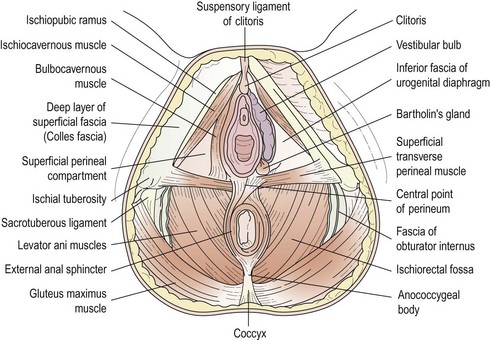

Vestibule

The vestibule is the cleft between the labia minora. The vagina, urethra, paraurethral (Skene’s) duct and ducts of the greater vestibular (Bartholin’s) glands open into the vestibule (see Figure 1.7). The vestibular bulbs are two masses of erectile tissue on either side of the vaginal opening, and contain a rich plexus of veins within bulbospongiosus muscle. Bartholin’s glands, each about the size of a small pea, lie at the base of each bulb and open via a 2 cm duct into the vestibule between the hymen and the labia minora. These glands secrete mucus, producing copious amounts during intercourse to act as a lubricant. They are compressed by contraction of the bulbospongiosus muscle.

The Bladder

Vesical interior

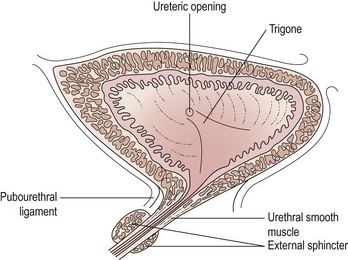

The mucous membrane of the bladder is only loosely attached to the underlying muscular coat, so that it becomes irregularly folded when the bladder is empty. A triangular area, the trigone, is immediately above and behind the urethral opening; the posterolateral angles are formed by the ureteric orifices (Figure 1.8). The mucous membrane here is redder in colour, smooth and attached firmly to the underlying muscle. The superior boundary is slightly curved, the interureteric ridge.

The Rectum

Relations

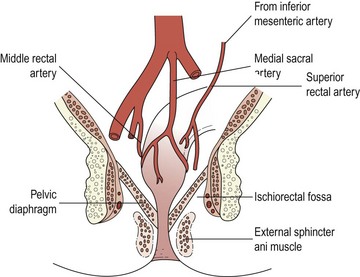

The relations of the rectum are particularly important because they can be felt on digital examination. Posteriorly are the lower three sacral vertebrae, the coccyx, median sacral and superior rectal vessels. Posterolateral relations are the piriformis, coccygeus and levator ani muscles, plus the third, fourth and fifth sacral and coccygeal nerves. Below and lateral to the levator ani muscle is the ischiorectal fossa (Figure 1.9).

Pelvic Musculofascial Support

Pelvic peritoneum

On either side of the uterus, a double fold of peritoneum passes to the lateral pelvic side walls, the broad ligament. These two layers, anteroinferior and posterosuperior, enclose loose connective tissue, the parametrium. At the upper border, between the two layers, is the fallopian tube. The mesentery between the broad ligament and the fallopian tube is called the mesosalpinx, and that between the broad ligament and the ovary, the mesovarium (see Figure 1.3). Beyond the fallopian tube, the upper edge of the broad ligament, as it passes to the pelvic side wall, forms the infundibulopelvic ligament, or suspensory ligament of the ovary, and contains the ovarian blood vessels and nerves. Between the fallopian tube and the ovary, the mesosalpinx contains the vestigial epoophoron and paroophoron. After crossing the ureter, the uterine vessels pass between the layers of the broad ligament at its inferior border. They then ascend the ligament medially and anastomose with the ovarian vessels.

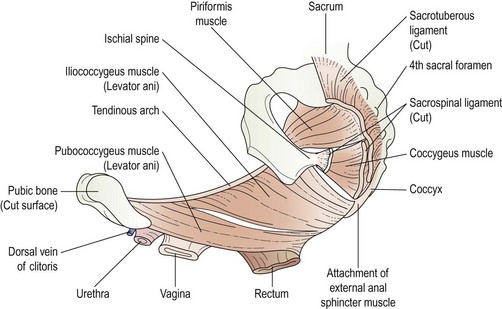

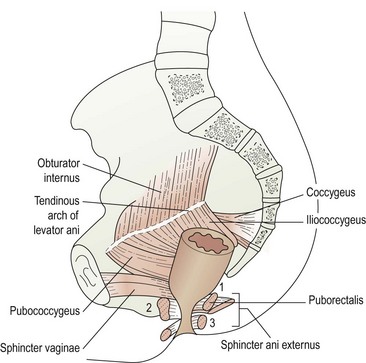

Pelvic musculature (Figures 1.10 and 1.11)

Most of the side wall of the lesser pelvis is covered by the fan-shaped obturator internus muscle which is attached to the obturator membrane and the neighbouring bone. The fibres run backwards and turn laterally at a right angle to emerge through the lesser sciatic foramen. The side wall is covered medially by the obturator fascia (Figure 1.12).

Blood Supply to the Pelvis

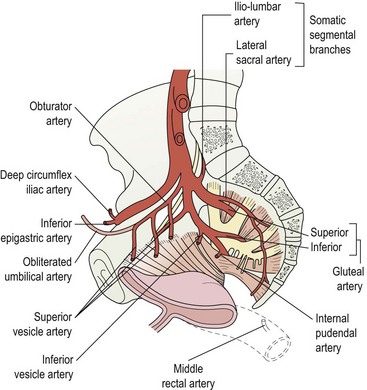

Internal iliac artery and its branches

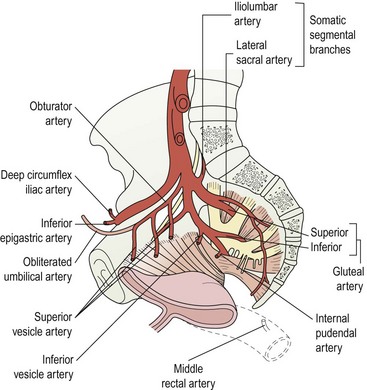

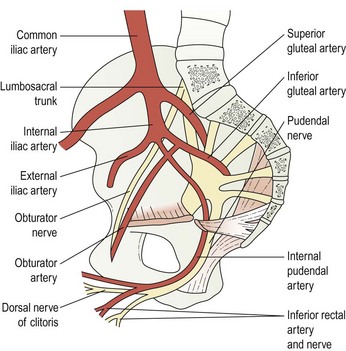

The internal iliac arteries are 4 cm long and descend to the upper margin of the greater sciatic foramen where they divide into anterior and posterior divisions (Figure 1.13). In the fetus, they are twice as large as the external iliac vessels and ascend the anterior wall to the umbilicus to form the umbilical artery. After birth, with the cessation of the placental circulation, only the pelvic portion remains patent; the remainder becomes a fibrous cord, the lateral umbilical ligament. The ureter runs anteriorly down the artery and the internal iliac vein runs behind.

Figure 1.13 The blood supply to the pelvic viscera is derived in the main from the internal iliac artery.

The anterior division has seven main branches. The superior vesical artery runs anteroinferiorly between the side of the bladder and the pelvic side wall to supply the upper part of the bladder. The obturator artery passes to the obturator canal and thence to the adductor compartment of the thigh. Inside the pelvis, it sends off iliac, vesical and pubic branches (Table 1.1).

| Organ | Artery | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| Ovary |

The uterine artery passes along the root of the broad ligament and crosses above and in front of the ureter approximately 2 cm from the cervix. It then runs tortuously along the lateral margin of the uterus between the layers of the broad ligament. It supplies the cervix and the body of the uterus and part of the bladder, and one branch anastomoses with the vaginal artery to produce the azygos arteries. It ends by anastomosing with the ovarian artery (Figure 1.14). The branches of the uterine artery pass circumferentially around the myometrium, giving off coiled radial branches which end as basal arteries supplying the endometrium.

The internal pudendal artery, the smaller of the two terminal trunks of the internal iliac artery, descends anterior to the piriformis and, piercing the pelvic fascia, leaves the pelvis through the inferior part of the greater sciatic foramen, crosses the gluteal aspect of the ischial spine and enters the perineum through the lesser sciatic foramen (Figure 1.15). It then traverses the pudendal canal with the pudendal nerve, approximately 4 cm above the ischial tuberosity. It then proceeds forwards above the inferior fascia of the urogenital diaphragm and divides into a number of branches. The inferior rectal branch supplies the skin and musculature of the anus, and anastomoses with the superior and middle rectal arteries; the perineal artery supplies much of the perineum, and small branches supply the labia, vestibular bulbs and vagina. The artery terminates as the dorsal artery of the clitoris.

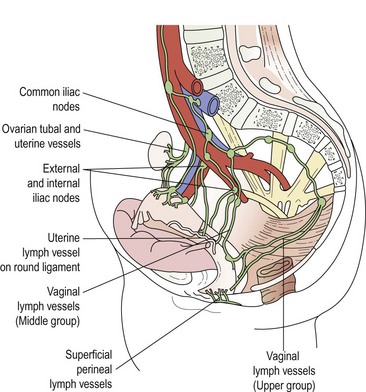

Lymphatic Drainage of the Pelvis

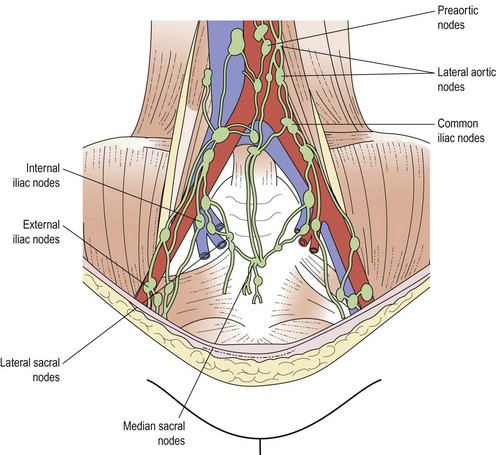

The lymph drainage of most other structures within the pelvis is via more outlying groups of lymph nodes associated with the iliac vessels. The common iliac lymph nodes are grouped around the common iliac artery and are usually arranged in medial, lateral and intermediate chains. They receive efferents from the external and internal iliac nodes, and send efferents to the lateral aortics (Figure 1.16).

The external iliac nodes lie on the external iliac vessels and are in three groups: lateral, medial and anterior. They collect from the cervix, upper vagina, bladder, deeper lower abdominal wall and inguinal lymph nodes. Inferior epigastric and circumflex iliac nodes are associated with these vessels and can be considered to be outlying members of the external iliac group (Table 1.2).

| Organ | Lymph nodes |

|---|---|

The internal iliac nodes, which surround the internal iliac artery, receive afferents from all the pelvic viscera, deeper perineum, and muscles of the thigh and buttock. The obturator lymph node, sometimes present in the obturator canal, and the sacral lymph nodes on the median and lateral sacral vessels can be considered to be outlying members of this group (Figure 1.17).

Figure 1.17 The lymphatic drainage of the female reproductive organs.

Semi-diagrammatic after Cunéo and Marcille 1901, Bull. Soc. Anat. Paris 3,653.

The deep inguinal (femoral) lymph nodes, varying from one to three, are on the medial side of the femoral vein. They receive efferents from the deep femoral vessels and some from the superficial inguinal nodes; one, the node of Cloquet, is thought to drain the clitoris. Efferents from the deep nodes pass through the femoral canal to the external iliac group (Figure 1.18).

KEY POINTS