CHAPTER 9 Postoperative care

Routine Postoperative Care

Bladder care

In women undergoing major gynaecological surgery, a urinary catheter is usually inserted just before the operation to keep the bladder empty throughout the procedure. This helps to minimize the risk of bladder injury and allows good access to the surgical field. Post operatively, the catheter is kept in place during the acute recovery phase for the patient’s comfort, to allow monitoring of urine output and to avoid urinary retention due to the general anaesthetic or pain. The catheter should be removed as soon as the patient is able to mobilize and void comfortably. Early removal of the catheter is important as prolonged catheterization may be associated with an increased risk of urinary tract infection (Schiøtz and Tanbo 2006). In patients who sustained a bladder injury during surgery, the catheter should be kept for 7–10 days to allow full healing of the bladder wall, and many gynaecologists would perform a systogram prior to removing the catheter.

Postoperative voiding difficulty is a common problem in gynaecological surgery, especially following bladder neck operations, and can be due to spasm, oedema or tenderness of parauretheral tissue. It is also common following radical hysterectomy due to extensive perivesical dissection that interferes with the nerve and blood supply to the bladder. Other contributing factors include cystitis and psychogenic factors. Failure to pass urine could also occur as a result of regional anaesthesia (which may cause bladder overdistension and atony) and abdominal pain, which may inhibit the initial voluntary phase of voiding. Following bladder neck surgery, most voiding difficulty resolves within 1 or 2 weeks of surgery, but up to 20% of women can continue with this problem for an extended period (up to 6 months) before being able to void normally (Smith and Cardozo 1997).

Drains

Intraperitoneal (pelvic) drains have been associated with an increased incidence of infection, and should only be used when the benefits outweigh the risks. Evidence from recent randomized trials and systematic reviews is against the routine use of drains. A recent large randomized trial of drains compared with no drains following radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection concluded that drains can be safely omitted in the absence of excessive bleeding during surgery or oozing at the end of surgery (Franchi et al 2007). A systematic review evaluating the value of routine suction drains after retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy in gynaecological tumours concluded that the prophylactic use of continuous suction drains is associated with a significant increase in morbidity and should be avoided (Bacha et al 2009). On the other hand, drainage of surgical wounds (especially clean-contaminated wounds) using a closed-suction system has been used prophylactically to reduce wound infection (Panici et al 2003).

Postoperative pain management

Effective relief of postoperative pain is of paramount importance as it offers significant psychological and physiological benefits to the recovering patient. Not only does it mean a smooth postoperative course with earlier discharge from hospital, but it also helps to reduce the incidence of complications (Nagaratnam et al 2007). In addition, there is evidence that good pain relief can reduce the onset of chronic pain syndromes. Inadequate pain management could lead to reduced deep breathing, causing impaired oxygenation. It can also cause inability to cough and clear lung secretions which may lead to lung atelectasis. Pain reduces a patient’s mobility, leading to slower recovery and increased risk of morbidities such as deep vein thrombosis (DVT). The benefits of good postoperative pain management are summarized in Table 9.1.

| Improved recovery | Patient satisfaction |

| Wound healing | |

| Early mobilization | |

| Early hospital discharge | |

| Reduced morbidities | Respiratory complications |

| Tachycardia and dysrhythmias | |

| Thromboembolic events | |

| Acute coronary syndromes | |

| Chronic pain syndrome |

The first step in achieving good pain control is preoperative prediction and accurate postoperative assessment of the degree of pain. Such pain is subjective and can vary greatly in severity between patients from almost no pain to very severe pain. There are two main factors determining the degree of postoperative pain: firstly, the nature, extent and site of the surgery; and secondly, factors related to the patient including fear, anxiety and pain threshold. A previous experience of postoperative pain may also infuence the patient’s expectation and perception of pain. It is therefore important to plan postoperative pain management through consultation between the surgeon and the anaesthetist based on the predicted pain severity. It is also important to explain to the patient the expected degree of pain and the steps that will be taken to ensure effective pain relief afterwards. It is usually helpful to establish the patient’s expectations of pain before surgery. This approach has been shown to minimize the patient’s fear and anxiety from pain and to reduce the requirement for postoperative analgesia (Karanikolas and Swarm 2000).

Methods of assessment

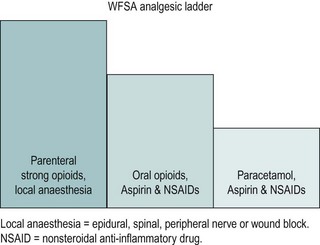

The analgesic ladder

The World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists’ analgesic ladder, which has been developed to treat acute pain, can be utilized for postoperative pain (Charlton 1997; Figure 9.1). In women undergoing major gynaecological surgery, the initial pain can be expected to be severe and may need injections of strong opioids [e.g. morphine, preferably by a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) system], which can be combined with local anaesthesia. As pain decreases with time, analgesia can be stepped down and parenteral opioids can be gradually replaced by the oral route. Strong oral opioids (e.g. oromorph) can be given, to be gradually replaced with a combination of peripherally acting agents (e.g. paracetamol and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs) and weak opioids (e.g. codeine phosphate). The final step is when the pain can be controlled by peripherally acting agents alone.

Wound care

Good wound care will promote healing and minimize complications such as infection, haematoma formation or dehiscence. Wound care begins during surgery with careful handling of tissues, avoidance of cautery for skin incision, meticulous haemostasis, good closure techniques and avoidance of excessive traction on the skin edges (Boesch and Umek 2009). At the end of surgery, a wound dressing is applied, mainly to cover the fresh wound to prevent seepage of serum or blood, but this does not have any protective effect against infection. It should be removed on the first postoperative day when the wound has become dry. Any serous or serosanguinous discharge can be squeezed out by gentle pressure on the wound edges. Patients can be allowed a shower, but should keep the wound dry and clean. Sutures and staples can be removed from transverse wounds after 4–5 days, but vertical wounds usually require 7–10 days to heal.

Wound infection

Wound infection occurs in 3–5% of clean wounds and 10–20% of clean-contaminated wounds in the absence of antibiotic prophylaxis. It usually presents by the fifth postoperative day as erythema, induration and pain in the area surrounding the incision, and may be associated with pyrexia. A wound swab should be taken for culture, and broad-spectrum antibiotics should be given. If the infection progresses to pus formation under the suture line, this should be drained. Usually, at this stage, the wound separates either partially or completely, allowing drainage. However, if the wound remains intact or if the separation is only small, the wound should be opened (in theatre if necessary) to allow drainage. If there is a significant delay in healing with development of devitalized tissue, the wound should be opened in theatre, explored, debrided and packed with gauze, followed by twice-daily dressing changes. At this stage, the tissue viability team and microbiologists should be involved in the care of this chronically infected wound to ensure that the most appropriate dressings and treatments are given. Negative pressure wound therapy may be considered in these wounds to promote the production of granulation tissue and encourage neovascularization (Walsh et al 2009).

Necrotizing fasciitis

Necrotizing fasciitis is a rare but life-threatening and rapidly progressive infection of the superficial fascia and subcutaneous tissues (Addison et al 1984). It often occurs in diabetic and immunosuppressed patients, but can also affect women with other chronic illnesses. It is characterized by dusky and friable subcutaneous tissue with serous drainage from a small wound that may be separate from the original incision wound. It can also occur on the vulva or perineum, often not related to surgery. There is extensive tissue necrosis and a moderate or severe systemic toxic reaction. Very radical excision is essential with antibiotics and supportive therapy.

Postoperative feeding

Traditionally and for many years, postoperative oral intake of fluid and food has been delayed until the recovery of bowel function (return of bowel sounds and passage of flatus) from the temporary postoperative ileus. This was believed to be necessary to avoid vomiting and severe paralytic ileus. However, this practice has not been supported by good scientific evidence. A recent systematic review of early (<24 h) compared with delayed oral intake after major abdominal gynaecological surgery has provided evidence in favour of early oral intake. The study has shown early postoperative feeding to be safe and associated with a reduced length of hospital stay, but with an increase in the incidence of nausea (Charoenkwan et al 2007). Early feeding was not associated with an increase in complications such as ileus, vomiting or abdominal distension. However, the authors concluded that the timing of postoperative feeding should be individualized according to each patient’s circumstances. In patients undergoing benign gynaecological procedures without significant insult to the gastrointestinal tract, early postoperative oral intake should be encouraged. On the other hand, feeding should be delayed in women at high risk of paralytic ileus (e.g. following extensive and prolonged procedures with excessive handling of the bowel).

Mobilization and physiotherapy

The benefits of early postoperative mobilization have been established since the 1940s (Brieger 1983). It reduces the muscle loss associated with inactivity, hastens recovery and reduces the incidence of pulmonary complications. Other benefits include a reduction in the risk of thromboembolic disease and respiratory infection. Mobilization involving an upright position appears to be of greatest benefit in the early postoperative period, with evidence of improvements in pulmonary function (Nielsen et al 2003), prevention of functional decline and possibly a positive effect on depression and anxiety (Brooks-Brunn 1995). Early involvement of skilled physiotherapists is essential to facilitate early mobilization and to deal with the problems arising from prolonged postoperative recovery. In particular, physiotherapists play an important role in the prevention and treatment of respiratory infection.

Recognition and Management of Postoperative Complications

Haemorrhage

When internal haemorrhage is suspected, whole blood should be immediately cross-matched and transfused as soon as available. In the mean time, hypovolaemia should be corrected by a colloid or crystalloid intravenous fluid until blood becomes available. The debate over the value of colloid vs crystalloid preparations for volume replacement remains unresolved. A recent Cochrane systematic review by Perel and Roberts (2007) concluded that the continued use of colloids in favour of crystalloids is not supported by evidence from randomized controlled trials and does not improve the outcome of treatment. An urgent full blood count and coagulation screen should be arranged. The coagulation status should be monitored repeatedly during the resuscitation of the patient due to the risk of consumptive coagulopathy. A haematologist should be consulted if there is any abnormality with the clotting system. The next step is for the surgeon to decide whether or not the patient should be taken back to theatre for exploration and achievement of haemostasis. Timing in these cases is critical as any delay in decision could have fatal consequences if the patient enters a state of irreversible shock or disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. On the other hand, rushing the patient back to theatre when conservative management may have been enough will unnecessarily subject the patient to the risks of repeated anaesthetic and surgery. More often, the bleeding is due to generalized ooze, and adequate haemostasis will be difficult to achieve surgically. In some cases, therefore, it may be better to continue the transfusion and correct any coagulation defect rather than to re-explore.

If a decision is made for surgical exploration, the patient should be taken to theatre after initial resuscitation. Patients bleeding vaginally after a hysterectomy could be examined vaginally under anaesthesia. The vault can be reopened and, if a bleeder is identified (usually vaginal branch of uterine artery in one of the angles), it can be secured with a suture. Once haemostasis has been achieved, the vaginal vault can be reclosed and a pack inserted if necessary. In all other cases, a relaparotomy should be performed and all the pedicles should be examined carefully. More recently, laparoscopy has been used successfully for exploration and establishment of haemostasis in patients with postoperative haemorrhage (Sobolev et al 2005). Intra-abdominal bleeding frequently originates from ovarian vessels. These must be identified clearly and separated from the ureter before the application of diathermy or a ligature. Sometimes, it can be difficult to localize the bleeding point and it may be venous rather than arterial. In these situations, compression with large packs for a few minutes can be effective, or will at least reduce the general ooze, allowing the main bleeding sites to be visualized clearly and dealt with. It is always important to ensure safety of the ureter by palpation or dissection before suturing. If effective haemostasis cannot be achieved, bilateral internal iliac artery ligation or angiographic embolization of bleeding vessels should be considered provided that expertise is available. Failure of haemostasis could be due to coagulopathy, which should be corrected promptly with input from the haematologist. Fresh frozen plasma, which contains all the protein constituents of plasma including the coagulation factors, is used to replace these factors in consumptive coagulopathy. Cryoprecipitate contains a high concentration of fibrinogen that may be required in massive blood transfusion. If haemostasis is impossible, the bleeding site could be compressed with several large packs, followed by closure of the abdomen. The packs should be removed under general anaesthetic after 24–48 h.

Infection and pyrexia

Most major gynaecological procedures (e.g. abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy) fall into the clean-contaminated category (see Chapter 7) and are associated with an infection rate of 10–20% in the absence of antibiotic prophylaxis. In a meta-analysis of 25 randomized controlled trials, involving a total of 3604 women, antibiotic prophylaxis was found to reduce the incidence of infection after total abdominal hysterectomy from 21% to 9% (Mittendorf et al 1993). On the other hand, clean wounds which are performed under complete aseptic conditions are associated with infection rates of 1–5% without prophylaxis. Clean procedures include most adnexal surgeries, laparoscopic procedures and subtotal hysterectomy. Antibiotic prophylaxis does not decrease infection rates following these procedures and should not be given.

Postoperative fever occurring within the first 48 h is not usually caused by an infective process, but may be associated with haematoma formation or pulmonary atelectasis. Later development of pyrexia (after 72 h) is more likely to be infective in origin. The most common site of postoperative infection is the urinary tract (day 3), followed by wound infections (day 5) and collections. Non-infective causes of pyrexia such as DVT should also be considered in the differential diagnosis. Urinary tract infections are not usually associated with urinary symptoms; when suspected, this should be confirmed with urine microscopy and culture. The incidence of urinary tract infection is not changed by the use of prophylactic antibiotics (Brown et al 1988), and is mainly increased with the use of perioperative catheterization. Wound infection usually becomes manifest on the fifth postoperative day (see above). Swinging pyrexia, which persists despite intensive antibiotic therapy, may indicate an infected collection (e.g. pelvic abscess). An ultrasound or computed tomography (CT) scan of the pelvis and abdomen should be performed in these cases to detect any collection. If identified, infected collections not responding to antibiotics may need surgical evacuation. This could be carried out either via a vaginal route (especially after vaginal hysterectomy) or through a laparotomy.

Sepsis is a systemic response to infection which, in severe cases, can lead to septic shock manifested by hypotension and multiple organ failure (Wheeler and Bernard 1999). This requires prompt resuscitation (in an intensive care unit) and aggressive eradication of the source of infection with broad-spectrum antibiotics and surgery if appropriate (Tamussino 2002).

Venous thromboembolism

In the absence of thromboprophylaxis, patients undergoing major (>30 min) general and gynaecological surgery have a significant risk of both asymptomatic (approximately 30%) and symptomatic (approximately 8%) venous thromboembolism (Table 9.2). The risk increases with the number of risk factors (Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2002). Women in the high-risk category should be counselled carefully before surgery, and referred to a haematology clinic for risk assessment and advice on perioperative management. The risk factors and thromboprophylaxis have been discussed in Chapter 7.

Table 9.2 Risks of venous thromboembolism following general and gynaecological surgery in the absence of thromboprophylaxis

| Type of venous thromboembolism | Risk (%) |

|---|---|

| Asymptomatic DVT | 25 |

| Asymptomatic proximal DVT | 7 |

| Symptomatic DVT | 6 |

| Symptomatic non-fatal PE | 1–2 |

| Fatal PE | 0.5 |

DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism.

Source: Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network 2002 Prophylaxis of Venous Thromboembolism. SIGN, Edinburgh.

Bowel complications

Paralytic ileus

Abdominal gynaecological surgery is usually followed by a physiological ileus due to manipulation of the bowel. The small bowel typically regains function within hours. The stomach regains activity in 1–2 days and the colon regains activity in 3–5 days (Cameron 2001). Postoperative adynamic ileus or paralytic ileus is defined as gut ileus persisting beyond 3 days following surgery (Livingston and Passaro 1990). Paralytic ileus is uncommon following benign gynaecological procedures as they are not usually associated with significant insult to the bowel.

The majority of patients will improve with conservative management by resting of the bowel, IV fluids and nasogastric tube drainage. Electrolyte imbalance, especially hypocalcaemia, should be corrected. Unresolved cases should be investigated for potentiating factors such as intraperitoneal abscess or retroperitoneal haematoma, which should be drained under radiological control (Gerzof et al 1981).

Bowel injury

Fortunately, inadvertent bowel injury is uncommon during benign gynaecological surgery with an incidence of 0.3–0.8%, with the majority (70%) being minor lacerations (Dicker et al 1982). The small bowel is the site of injury in approximately 75% of cases. Abdominal rather than vaginal or laparoscopic surgery is associated with a higher rate of damage. The incidence of bowel damage during laparoscopic surgery is 0.5% (Garry and Phillips 1995). The site, extent and timing of presentation of bowel injury will determine the presentation, management and outcome. Postoperative large bowel leak is a serious and life-threatening complication. Risk factors for bowel injury include adhesions, endometriosis, sepsis, obesity, and previous pelvic or abdominal radiotherapy.

Intraoperative detection of bowel injury

There are three main types of bowel injury: direct trauma with sharp instruments, thermal injury with electrosurgery, and devascularization with subsequent necrosis due to extensive dissection. The former injury results in intraoperative perforation or laceration. This is not always easy to recognize and requires a significant amount of experience. The damage may be detected if it occurs on a visible bowel surface or when there is an obvious leak of bowel contents (e.g. faeces). However, in a significant proportion of patients, neither of these is obvious and the damage can easily be missed. Small bowel contents are not usually easy to notice, which leads to 60% of small bowel injuries being missed (Hill 1994). To minimize the possibility of missing bowel damage, it is important to have a high level of suspicion, especially in difficult or high-risk cases. Consideration should be given to asking a colorectal surgeon to explore the bowel for suspected damage. In patients suspected to have bowel injury during extensive laparoscopic surgery in the cul-de-sac, a 30 cc Foley catheter could be inserted into the rectum. With clamping the bowel above the site of dissection, the pelvis is filled with physiological solution and air injected through the Foley catheter by a 100 cc syringe. The appearance of bubbles in the solution will indicate perforation. Alternatively, a 50% betadine solution could be injected and the bowel observed for trailers of betadine leakage.

Pulmonary complications

Postoperative pulmonary complications after abdominal surgery include chest infection, atelectasis, pulmonary oedema and pulmonary embolism. Atelectasis is the most common pulmonary complication, and has been estimated to occur in 20% of patients having upper abdominal surgery and 10% of patients having lower abdominal surgery (Bartlett 1980).

Risk factors for postoperative pulmonary complications include smoking, old age, obesity, upper respiratory tract infection, positive cough test (recurrent coughing after deep inspiration and initial cough), perioperative nasogastric tube and long duration of anaesthesia (McAlister et al 2005, Pappachen et al 2006). Arterial blood gas analysis will determine the severity of the problem. Initial treatment is a higher concentration of oxygen supplied via an oxygen mask. Consideration of assisted ventilation should be made in patients unable to maintain saturation >90% or with PO2 <8.0 kPa with referral to a critical care specialist.

Cardiovascular complications

Any patient receiving a general anaesthetic is at increased risk of developing myocardial ischaemia, especially if there is underlying heart disease. Obtaining a good medical history of cardiac disease is very important in predicting cardiac complications. Elective surgery should be delayed in patients with a history of myocardial infarction within the preceding 6 months (Doshani and Shafi 2003).

KEY POINTS

Addison WA, Livengood CH, Hill GB, Sutton GP, Fortier KJ. Necrotizing fasciitis of vulvar origin in diabetic patients. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1984;63:473-479.

Bacha OM, Plante M, Kirschnick LS, Edelweiss MI. Evaluation of morbidity of suction drains after retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy in gynecological tumors: a systematic literature review. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer. 2009;19:202-207.

Bartlett RH. Pulmonary pathophysiology in surgical patients. Surgical Clinics of North America. 1980;60:1132.

Boesch CE, Umek W. Effects of wound closure on wound healing in gynaecologic surgery: a systematic literature review. Journal of Reproductive Medicine. 2009;54:139-144.

Brieger GH. Early ambulation. A study in the history of surgery. Annals of Surgery. 1983;197:443-449.

Brooks-Brunn JA. Postoperative atelectasis and pneumonia: risk factors. American Journal of Critical Care. 1995;4:340-349.

Brown EM, Depares J, Robertson AA, et al. Amoxycillin-clavulanic acid (Augmentin) versus metronidazole as prophylaxis in hysterectomy: a prospective, randomised clinical trial. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1988;95:286-293.

. Current Surgical Therapy. Cameron JL, editor, 7th edn. Mosby, Chicago, 2001.

Charlton JE. The management of postoperative pain. Update in Anesthesia. 1997;7:2-17.

Charoenkwan K, Phillipson G, Vutyavanich T 2007 Early versus delayed (traditional) oral fluids and food for reducing complications after major abdominal gynaecologic surgery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 4: CD004508.

Dicker RC, Greenspan JR, Strauss LT, et al. Complications of abdominal and vaginal hysterectomy among women of reproductive age in the United States. The Collaborative Review of Sterilisation. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1982;144:841-848.

Doshani A, Shafi M. Pre- and post-operative care in gynaecology. Current Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 2003;13:151-158.

Franchi M, Trimbos JB, Zanaboni F, et al. Randomised trial of drains versus no drains following radical hysterectomy and pelvic lymph node dissection: a European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer–Gynaecological Cancer Group (EORTC–GCG) study in 234 patients. European Journal of Cancer. 2007;43:1265-1268.

Garry R, Phillips R. How safe is the laparoscopic approach to hysterectomy. Gynaecological Endoscopy. 1995;105:77-80.

Gerzof SG, Robbins AH, Johnson WC. Percutaneous catheter drainage of abdominal abscesses. New England Journal of Medicine. 1981;305:193-197.

Hill DJ. Complications of the laparoscopic approach. Baillières Clinical Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1994;8:865-879.

Karanikolas M, Swarm RA. Current trends in perioperative pain management. Anesthesiology Clinics of North America. 2000;18:575-599.

Livingston EH, Passaro EPJr. Postoperative ileus. Digestive Diseases and Science. 1990;35:121-132.

McAlister FA, Bertsch K, Man J, Bradley J, Jacka M. Incidence and risk factors for pulmonary complications after nonthoracic surgery. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2005;171:514-517.

Mittendorf R, Aronson MP, Berry RE, et al. Avoiding serious infections associated with abdominal hysterectomy: a meta-analysis of antibiotic prophylaxis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1993;169:1119-1124.

Nagaratnam M, Sutton H, Stephens R. Prescribing analgesia for the surgical patient. British Journal of Hospital Medicine. 2007;68:M7. M10

Nielsen KG, Holte K, Kehlet H. Effects of posture on postoperative pulmonary function. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2003;47:1270-1275.

Panici PB, Zullo MA, Casalino B, Angioli R, Muzii L. Subcutaneous drainage versus no drainage after minilaparotomy in gynecologic benign conditions: a randomized study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2003;188:71-75.

Pappachen S, Smith PR, Shah S, Brito V, Bader F, Khoury B. Postoperative pulmonary complications after gynecologic surgery. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2006;93:74-76.

Perel P, Roberts I 2007 Colloids versus crystalloids for fluid resuscitation in critically ill patients. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 17: CD000567.

Schiøtz HA, Tanbo TG. Postoperative voiding, bacteriuria and urinary tract infection with Foley catheterization after gynecological surgery. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica. 2006;85:476-481.

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Prophylaxis of Venous Thromboembolism. Edinburgh: SIGN; 2002.

Smith RN, Cardozo L. Early voiding difficulty after colposuspension. British Journal of Urology. 1997;80:911-914.

Sobolev VE, Dudanov IP, Alontseva NN, Bogdanova VS. [The role of laparoscopy in the diagnosis and treatment of early postoperative complications]. Vestn Khir Im I I Grek. 2005;164:95-99.

Tamussino K. Postoperative infection. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2002;45:562-573.

Walsh C, Scaife C, Hopf H. Prevention and management of surgical site infections in morbidly obese women. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009;113:411-415.

Wheeler AP, Bernard GR. Treating patients with severe sepsis. New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340:207-214.