Chapter 30 Surgery of Intramedullary Tumors

INTRODUCTION

Intramedullary spinal cord tumors are rare, accounting for about 4–10% of all central nervous system tumors. Astrocytomas and ependymomas are the most commonly encountered spinal intramedullary tumors, and are found in up to 70% of all spinal intramedullary tumors. Most intramedullary cord tumors are benign gliomas. The determination of the optimum treatment of these tumors is controversial. In the past, there has been the traditional approach of biopsy, dural decompression, and radiation therapy, despite the recognition that after a relatively short remission, progression ensues, and the patient quickly becomes seriously disabled. This treatment was based on the assumption that astrocytomas are infiltrative tumors and that radical resection poses a high probability of inflicting neurological injury to the patient. These assumptions are debatable because most of these neoplasms are low-grade lesions. Recent advances in microsurgical technology, such as the ultrasonic aspirator, laser, intraoperative ultrasound, and intraoperative neurophysiological monitoring, permit a safer aggressive surgical resection. A radical surgical approach for intramedullary spinal cord tumor has been proposed by some surgeons. The radical resection without adjuvant treatment has been the rule for the intramedullary lesions.1 The postoperative functional performance is determined mainly by the preoperative deficits. The rate of aggravation is less than 20%. The most influencing prognostic factor for the postoperative result is the extent of tumor removal.2 The goal of surgery is maximal removal of the tumor mass without additional functional deficits.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUES OF INTRAMEDULLARY CORD TUMOR RESECTION

DURAL INCISION

A midline dural incision is made. Great care should be taken not to injure the arachnoid membrane. Under the microscope, the arachnoid membrane is sharply incised. The arachnoid membrane is tacked up by suturing it to the dura. Most tumors are totally intramedullary and are not apparent on surface inspection. An intraoperative ultrasound may be used to localize and determine the rostrocaudal tumor extent.3

IDENTIFICATION OF MIDLINE

There are two routes to intramedullary tumors: through the posterior midline or through a posterolateral myelotomy through the root entry zone.4 The former follows the posterior median sulcus, and the spinal cord is split between the two posterior columns.

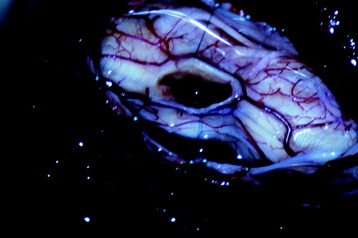

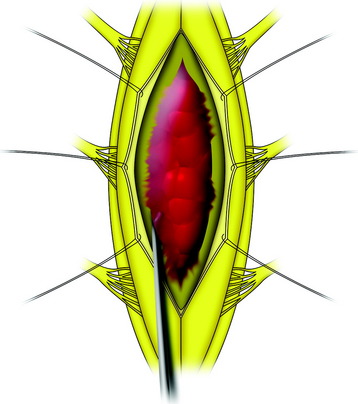

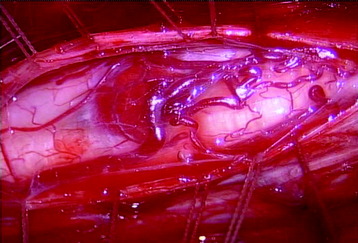

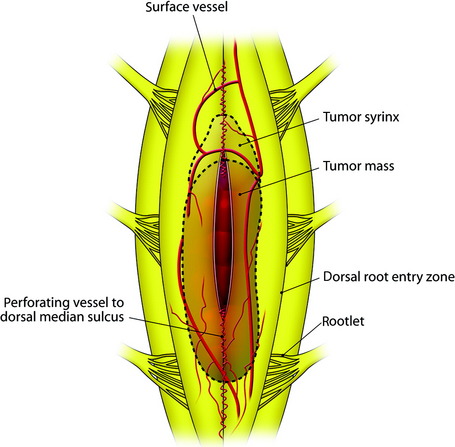

The midline of the spinal cord is anatomically identified with branches of the dorsal medullary vein penetrating the median sulcus. The thin membrane from the arachnoid attaches to the dorsal midline surface of the spinal cord (area posticum). Sometimes a spinal cord edema makes it difficult to identify the midline on the posterior surface of the spinal cord. The vessels usually are located off midline and do not constitute reliable markers. If the anatomical midline is not definite, the imaginary line is assumed from the bilateral dorsal root entry zone. The tumor-infiltrated spinal cord possesses a swollen appearance.5 In cases of a hypervascular mass or tumor hemorrhage, the bluish discoloration is seen through the surface of the spinal cord6 (Fig. 30-1).

MYELOTOMY

The myelotomy can be performed with a No. 11 blade, a No. 59 beaver-blade, a CO2 laser, or a neodymium:yttrium-aluminum garnet (Nd-YAG) contact laser.4 Some surgeons routinely use the latter during myelotomy. Compared with electrocauterization, this technique causes no artifact during electrophysiological monitoring.

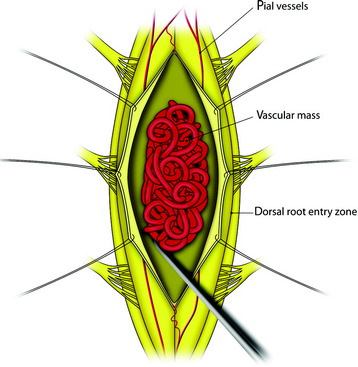

When the length of the myelotomy falls short, the resection margin cannot be identified. Discontinuous myelotomy is a viable technical option whenever the presence of large vessels on the median sulcus would make the standard midline myelotomy unsafe. After a small incision is made, the median sulcus is gently spread with the aid of microdissectors or microforceps to deepen the myelotomy until the tumor’s pole or cyst is exposed or opened both rostrally and caudally. The interface of the median sulcus usually can be identified by small vessels running over its surface, even if the midline has deviated to either side as a result of tumor compression (Fig. 30-2).

Fig. 30-2 At the interface of the median sulcus, the small vessels are penetrating into the pial surface.

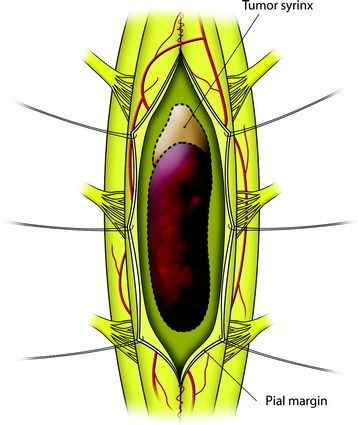

The mass is encountered about 2 cm deep from the surface. The whole length of the mass is exposed, then the incision margin of the pia is sutured with a fine 6-0 or 7-0 nylon to the reflected dura. The spinal cord tissue over the tumor mass is retracted to expose the tumor mass (Fig. 30-3).

DISSECTION OF THE TUMOR MASS

Ependymoma

The gross appearance is soft, friable, red to gray, and not encapsulated. Usually ependymomas have a smooth, glistening tumor surface. However, they are well-demarcated from the surrounding cord tissue, being dissected with blunt manipulation. The rostral end of the ependymoma accompanies the cyst, but the caudal part of the mass sometimes is connected to the central canal with a tough, fibrous band (Fig. 30-4). Large tumors may require internal decompression with an ultrasonic aspirator. The dissection for the ventral surface of the tumor mass is difficult because the feeding artery from the anterior spinal artery is usually found. The feeding arteries should be cauterized and cut on the side of the tumor mass with the tumor mass tractioned posteriorly.

Filum Ependymoma

Internal decompression is not used for small- and moderate-sized tumors because this may increase the risk of cerebrospinal fluid dissemination. In cases of large tumors, the tumor can insinuate among the roots and within the arachnoid sheaths of the cauda equina (Figs. 30-5 and 30-6). Tumor removal in these cases is necessarily piecemeal and will almost always be subtotal. Dense tumor attachments to the roots of the cauda equina present significant risks of postoperative neurological deficits.

Astrocytoma

The astrocytoma is dark red. The dorsal part of the mass shows relatively good demarcation. However, as the dissection proceeds ventrally, the infiltration of mass to surrounding tissue becomes definite. Dissection on the surface of an astrocytoma usually results in the development of laminated pseudo-planes (Fig. 30-7). Decompression is achieved with an ultrasonic aspirator and proceeds systematically from the center of the tumor radially to the surface. All aspects of the removal procedure should be carried out using spinal evoked potentials and motor stimulation. Although a clean plane does not exist for the majority of astrocytomas, there is often a difference in the color and consistency of the tumor with respect to the spinal cord. The tumor mass is darker and tougher than normal cord tissue. The resection begins within the tumor and proceeds to the periphery (centrifugal resection) until normal tissue is reached.

Hemangioblastoma

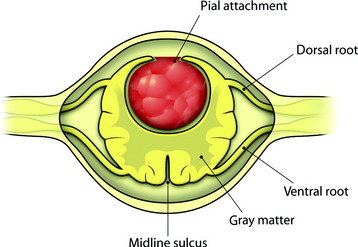

All tumors are located on the dorsal or dorsolateral surface of the spinal cord, and a conventional midline myelotomy is not required for exposure.7 After the dural opening, the tumor mass with dilated vessels is identified (Fig. 30-8). The arachnoid is sharply dissected from the surface of the hemangioblastoma and associated vessels. In general, the tumor is approached like an arteriovenous malformation, with special attention to feeding and draining vessels.8

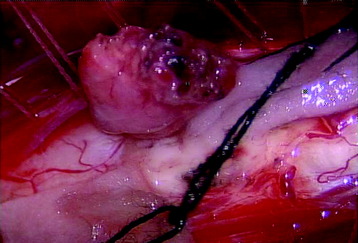

Tumor removal is facilitated by excision of the pial attachment as part of the tumor mass. The buried portion of the tumor within the spinal cord is dissected and delivered with traction on the pial base (Fig. 30-9). Occasionally the presence of stained gliotic tissue surrounding the tumor can make it difficult to identify the interface between the tumor and the spinal cord. Despite preoperative embolization, the continuous oozing after penetration is very disturbing when operating under microscope.

Internal decompression should not be performed because it results in severe tumor bleeding.9 Cautery on the tumor surface, however, usually shrinks it to a manageable size.

Cavernous Hemangioma

Cavernous hemangioma is the well-delineated lesion composed of abnormal microvessels without the inner normal neural tissue.10 The lesion shows mixed signal intensity on T1- and T2-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) with a surrounding low signal ring, which denotes hemosiderin ring deposition (Fig. 30-10). The typical appearance of a cavernous malformation is an inhomogeneous high-intensity signal on both T1- and T2-weighted images with a “dark” ring of hemosiderin surrounding and appearing hypo-intense on T1 and T2 weighting. Enhancement is not typical for cavernous malformations.4

Cavernous hemangiomas are described on gross finding as soft and spongy with a dark-blue to red-brown hue. Cavernous malformations are usually well-circumscribed, and a hemosiderin staining of the surrounding tissues caused by repeat bleeding can clearly define the plane of dissection. This discoloration is sometimes the only visual clue by which a cavernous malformation may be detected under the pial surface (Fig. 30-11). After the dural incision, the surface of the spinal cord appears swollen and of a dark red color. The myelotomy is performed on the midline or discolored portion. The myelotomy should be parallel to fiber tracts on the long axis of the spinal cord to minimize damage. In most cases, the dissection between the cavernoma and surrounding cord tissue can be accomplished without difficulty because there is a gliotic plane or hematoma (Fig. 30-12). Tongue-like extensions of the cavernous malformation can extend into the surrounding gliotic plane; this should be kept in mind during resection of the cavernous malformation to achieve complete excision. The resection of the lesion is performed using microcurettes and gentle suction aspiration. Handheld suction devices with thumb apertures offer controlled suction strength, which is critical to avoid damaging surrounding tissues. Typically, lesions will be removed in a piecemeal fashion, although some can be resected en bloc. Bleeding is seldom a problem with cavernous malformations because of their low-flow nature, and hemostasis should be accomplished using hemostatic agents and gentle compression. Venous draining anomalies are often associated with cavernous malformations and should be preserved because they may provide venous drainage for adjacent eloquent tissues. After hemostasis is obtained, careful inspection of the resection bed under high magnification is imperative to identify and further resect small “tongues” of cavernous malformation that may extend into the adjacent tissue.8 Incompletely resected lesions can recur and hemorrhage; therefore every attempt should be made to resect these lesions fully during the first surgery.

The pathophysiology of bleeding in the cavernous hemangioma is suggested in three ways.10,11 The first is the perilesional slow oozing of red blood cells through the cavern without significant bleeding, which causes a hemosiderin ring. The second is the intralesional hemorrhage (microhemorrhage) which can grow. The third is the overt and gross hemorrhage which can compress the surrounding neural tissue.

Dural Closure

Once the tumor has been resected and hemostasis is obtained, the tumor bed is irrigated with normal saline solution. The use of bipolar coagulation should be limited. The pia can be reapproximated with 8-0 interrupted nylon sutures. However, we prefer to leave the pia open. The dura is closed with 6-0 Prolene running sutures in a watertight fashion. The adequacy of the dural closure can be determined with a Valsalva maneuver by increasing airway pressure to 40 mm H2O. If part of the dura was resected with the base of the tumor (e.g., meningioma), dural patching with bovine pericardium or Gore-Tex (Gore-Tex Industries, Flagstaff, AZ) is used to prevent postoperative scarring.4 This technique reduces a patient’s risk of spinal cord tethering and minimizes the likelihood of recurrence, especially with meningiomas. The entire dural circumference can be replaced using fascia lata. The dural closure can be sealed with fibrin glue or Tisseel (Baxter Healthcare Corporation, Deerfield, IL).

CASE ILLUSTRATION

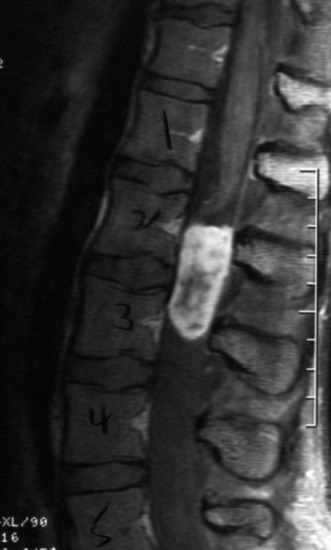

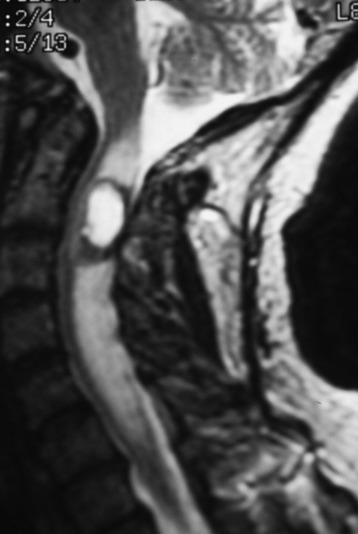

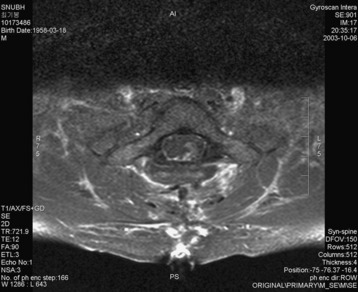

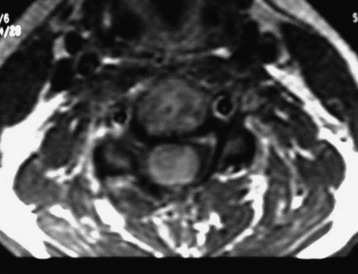

A 37-year-old male patient presented with right upper extremity paresthesia that had persisted for 5 years. On a preoperative imaging study, a well-enhancing cord mass was detected at the C7–T1 level (Fig. 30-13). On a T2-weighted image, the black signal void was seen in the tumor mass, and the dissection plane could be found between the tumor mass and the spinal cord tissue (Fig. 30-14). With this finding, the surgeons expected that the tumor location was extramedullary or near the surface if it was an intramedullary lesion. On an axial cut, the tumor mass occupied the whole cord area without identifiable cord tissue (Fig. 30-15).

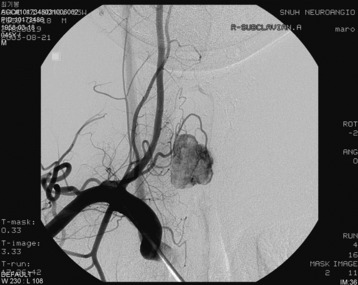

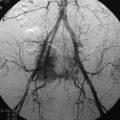

An angiogram showed that the tumor feeding vessel arose from the right costocervical trunk. After embolization, the tumor stain disappeared (Figs. 30-16 and 30-17).

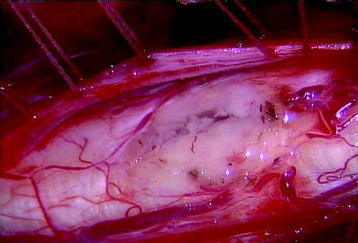

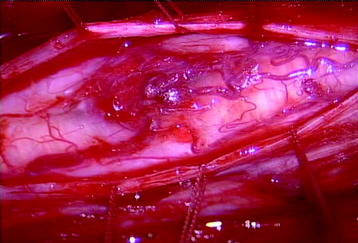

A total laminectomy was performed from C6 to T1. After the dural opening, the reddish mass was seen on the posterior surface of the spinal cord (Fig. 30-18). The mass was covered with arachnoid and pia mater. After arachnoid dissection, tortuous surface vessel was seen (Fig. 30-19). A pial dissection and retraction were performed. The interface between the tumor mass and surrounding cord tissue was relatively definite. The dissection plane could be found easily, and an en bloc removal was possible (Fig. 30-20). The gliotic plane was observed after tumor mass removal.

The postoperative MRI showed that no enhancing lesion surrounded the syrinx cavity (Fig. 30-21).

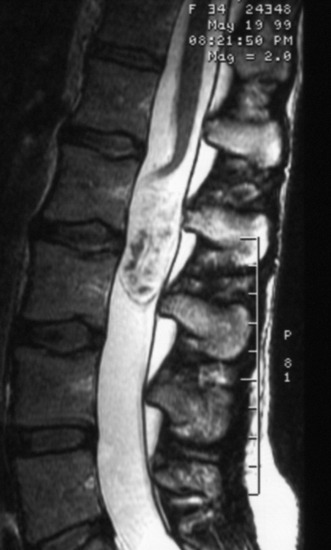

A 42-year-old female patient had suffered from posterior neck pain for 5 years and had developed clumsiness in both hands 5 months before being seen at the hospital. She complained of difficulty in walking for a long time. A neurological examination found her to be slightly quadriparetic. Sensory function was seen to be decreased in both hands. An MRI scan was recommended. It showed a well-enhancing mass lesion at the C3–7 region (Fig. 30-22). The mass accompanied a cystic lesion on the cephalad side of the solid mass. The spinal cord was swollen (Fig. 30-23). The surrounding normal spinal cord tissue was so thin that the surgeons could not identify the thickness. The operation was performed via the posterior approach. A total laminectomy was performed from C2 to C6. The laminectomy level was determined by the length of the tumor mass, including the cystic portion.

After the laminectomy and dural incision, the swollen spinal cord was exposed. A midline myelotomy was performed after the midline was determined as the imaginary line between both dorsal root entry zones. The tumor mass was found 2 mm deep into the myelotomy. The tumor dissection was performed with relative ease. Total removal was possible with the ventral cord tissue left intact. The cystic portion showed no lining tissue, which indicated that it was only a syrinx cavity. A postoperative MRI 6 months later found no enhancing dot and the cyst had collapsed (Fig. 30-24).