Chapter 53 Surgery for Male Infertility

INTRODUCTION

Infertility affects at least 15% of all couples, and male factor is involved in approximately half of these cases. Approximately half the men with male factor infertility will have problems that are surgically correctable: 40% of men will have a varicocele and 15% will have an obstruction, including those with a previous vasectomy.1 Treatment of surgically correctable male factors is cost-effective and can spare the female partner invasive procedures and potential complications associated with the use of assisted reproductive technologies.2–4

Detection of surgically correctable problems requires an appropriate male factor evaluation, including a history, physical examination, and at least two semen analyses. Further testing, such as endocrine or genetic testing, may be required, depending on the results of the preliminary evaluation. In addition to diagnosing correctable problems, some men may have significant underlying medical problems diagnosed during their evaluation.5,6

DIAGNOSTIC PROCEDURES

Transrectal Ultrasound

Ejaculatory duct obstruction is a rare cause of infertility, accounting for less than 1% of cases. Causes include congenital atresia or stenosis; utricular, müllerian, or Wolffian duct cysts; trauma; and infection. A seminal vesicle diameter of greater than 1.5cm is suggestive of ejaculatory duct obstruction, although there is no definite threshold for making the diagnosis.7–10

A partial form of ejaculatory duct obstruction may to be present in men with low semen volume and severe oligoasthenospermia. According to some investigators, this condition can be detected by transrectal ultrasound. However, no precise criteria for diagnosing partial ejaculatory duct obstruction is available, and currently this condition is considered investigational.7

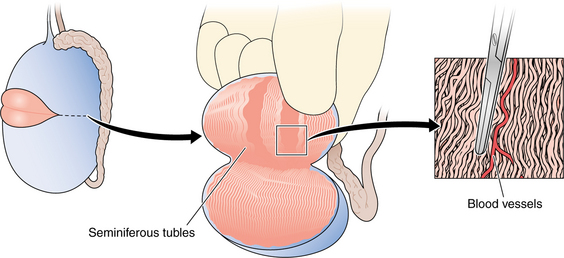

Testis Biopsy

The indications for a diagnostic testis biopsy are azoospermia with at least one palpable vas deferens.10–12 It must first be verified that the patient is indeed azoospermic by centrifuging the sample, resuspending the pellet, and repeating the microscopic examination.13 The primary purpose of a testis biopsy is to differentiate obstructive from nonobstructive azoospermia. Pathologic analysis should be performed to analyze the pattern of sperm production and to rule out intratubular germ cell neoplasia, which may occur in 0.4% to 1.1% of infertile men.10 Fixatives such as Bouin’s or zinc formalin allow for maintenance of the testicular architecture for pathologic examination.

A diagnostic classification system devised by Levin is useful in describing the pattern of sperm production.14 In the setting of azoospermia, more than 20 mature spermatids per tubule on histologic examination would be consistent with a sperm concentration of 10 million/mL, suggesting obstruction.15

The technique of diagnostic testis biopsy is straightforward. It can be performed through a small scrotal incision with local, regional, or general anesthesia on an outpatient basis. Delivery of the testis is usually not required for a standard biopsy. A biopsy can also be performed percutaneously with a biopsy gun or by fine-needle aspiration, although fewer tubules are obtained this way.16,17 To avoid injury to significant branches of the testicular artery, the biopsies should be taken from the medial or lateral aspect of the upper pole.18

If the testes are symmetric, a unilateral biopsy is sufficient to document obstruction. Bilateral biopsies are more important when attempting to maximize the chances for sperm retrieval.19

Vasography

The purpose of a vasogram is to assess the patency of the vas deferens. The indications for vasography are azoospermia, a normal FSH, a testis biopsy with normal spermatogenesis, and at least one palpable vas deferens.10,12

Virtually all vasal obstructions are iatrogenic. Vasal obstruction can be encountered after inguinal hernia repair or orchidopexy, retroperitoneal surgery such as renal transplantation and, of course, vasectomy. Vasography is not routinely necessary at the time of vasectomy reversal, however. Azoospermic men with normal semen volume, normal spermatogenesis on a testis biopsy, palpable vasa, and no history of inguinal, scrotal, or retroperitoneal surgery will most likely have epididymal obstruction.

Vasography can be performed with either a hemivasotomy or a puncture technique and should be performed only at the time of a planned reconstruction. The puncture technique is technically more difficult to perform. The advantage of the puncture technique is that it does not require separate closure of the vas deferens.20

If there is no difficulty with the injection, one can assume that the vas distal to the injection site is patent.10 A normal x-ray vasogram should demonstrate a barely perceptible but patent vasal lumen coursing from the scrotum through the inguinal canal to the pelvis, with filling of the ejaculatory ducts and bladder.

TREATMENT OF ACQUIRED OBSTRUCTION

Inguinal Vasal Obstruction

Obstruction of the vas deferens can occur after inguinal, scrotal, and retroperitoneal surgery.21 Reconstruction of the retroperitoneal vas is usually not possible secondary to retraction of the distal end, and reconstruction of the inguinal vas is challenging and in some cases not possible.

Inguinal vasal reconstruction begins with mobilization of the two ends of the vas deferens followed by a microsurgical anastomosis with either a modified one-layer or formal two-layer technique. Difficulties encountered with inguinal vasal reconstruction stem from the inability to isolate and mobilize the distal (abdominal) end and the dense scarring that occurs, particularly with mesh, after inguinal hernia repairs.22,23

In cases where there is inguinal vasal obstruction on one side and an atrophic testis with a normal ductal system on the contralateral side, strong consideration should be given to a trans-septal or “crossover” vasovasostomy because this is technically less complicated than performing an inguinal dissection and anastomosis. Sperm retrieval and in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (IVF/ICSI) should be considered as an alternative.24

Vasectomy Reversal

Vasectomy is one of the most popular forms of contraception and as many as 4% to 10% of men who undergo a vasectomy request a reversal.24 This procedure is performed as an outpatient with local, regional, or general anesthesia. Secondary epididymal obstruction can occur; in these cases vasoepididymostomy, rather than vasovasostomy, is required.25 Vasoepididymostomy is significantly technically more demanding than vasovasostomy. Vasovasostomy and vasoepididymostomy are usually performed through bilateral high scrotal incisions.

Vasovasostomy

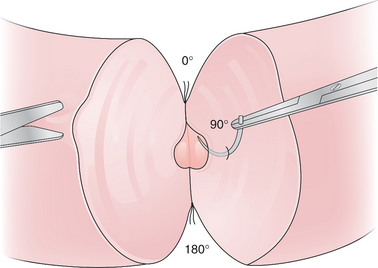

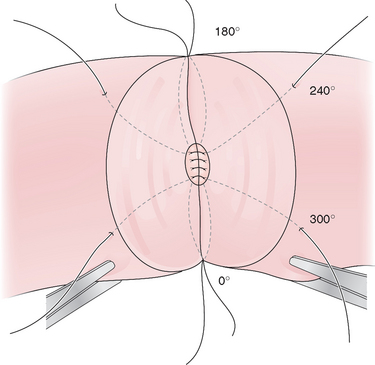

The vasal anastomoses can be performed with either a modified one-layer technique with 9-0 nylon or a formal two-layer technique with 10-0 and 9-0 nylon (Figs. 53-1 and 53-2).26 With the modified one-layer technique, four to six full-thickness 9-0 nylon sutures are placed with four to six 8-0 or 9-0 nylon sutures in the muscularis in between the full-thickness sutures. In the formal two-layer technique, the vasal mucosa is reapproximated as a separate layer with interrupted 10-0 nylon and the muscularis with 9-0 nylon.27

Vasoepididymostomy

The initial approach for vasoepididymostomy is similar to that for vasovasostomy. If thick, pasty vasal fluid without sperm is noted, vasoepididymostomy should be considered. The incisions are extended and the tunica vaginalis is opened to deliver the testis and spermatic cord. Typically, the site of epididymal obstruction can be identified by its distension and bluish brown discoloration. The vas deferens is mobilized distally to allow for sufficient length to reach the epididymis. This can require dissection up to the external ring with extension of the incision superiorly.

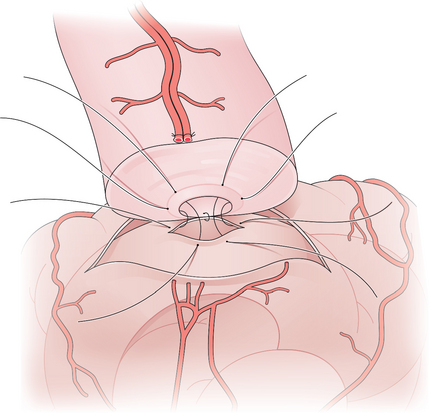

The vas deferens is then routed behind the cord to lie next to the epididymis and aligned with the epididymal tubule by placing 9-0 nylon sutures from the tunica of the epididymis to the muscularis of the vas deferens. In the traditional end-to-side technique five to eight 10-0 nylon sutures are placed into the open epididymal tubule and then to the mucosa of the vas deferens. The outer layer of the anastomosis is then completed by anastomosing the remainder of the epididymal tunic to the muscularis of the vas deferens with 9-0 nylon (Fig. 53-3).28 The scrotum is then closed in layers with absorbable suture.29

Figure 53-3 Vasoepididymostomy. A single epididymal tubule has been opened and sutured to the mucosa of the vas.

Newer techniques for vasoepididymostomy involve intusussception of the epididymal tubule into the lumen of the vas deferens. A triangulation technique with three double-arm 10-0 sutures was described by Berger and a two-suture technique was described by Marmar. With these techniques, the double-arm sutures are placed in the distended epididymal tubule before it is opened. The tubule is opened between the previously placed double-arm sutures and these are then placed in the corresponding position of the mucosa of the vas deferens. The outer layer of the anastomosis is completed with 9-0 nylon sutures from the tunica of the epididymis to the muscularis of the vas deferens.

The main advantages of these newer intusussception techniques are that the 10-0 sutures are easier to place in a distended tubule and the intusussception of the epididymis into the lumen of the vas deferens may reduce leakage. Patency may occur sooner than with traditional vasoepididymostomy, but pregnancy data for these newer techniques are generally lacking.30,31

Postoperative Course

The first semen analysis is checked between 4 and 12 weeks postoperatively and every 3 months thereafter. It can take as long as 6 months to see sperm return to the semen after vasovasostomy, and the average time to pregnancy is 1 year.32,33 It is not unusual to see lower sperm concentration and motility with the initial semen analyses, and it may take 3 to 6 months or longer to see the semen parameters reach a plateau.

Secondary restenosis of the anastomoses can occur in about 10% of cases with subsequent azoospermia.32,34 Sperm cryopreservation can circumvent this problem, but most men will not need the frozen sperm. After vasoepididymostomy, it can take as long as 1 year to see sperm return to the semen.32

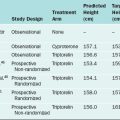

Success Rates

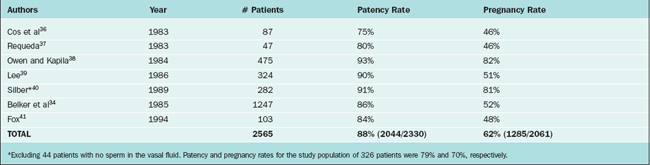

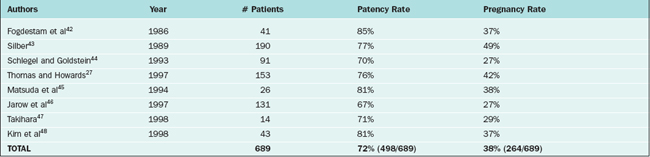

Patency rates for vasovasostomy and vasoepididymostomy range from 75% to 93% and 67% to 85%, respectively. Patency rates depend on the obstructive interval (time since the vasectomy), the quality of the vasal fluid noted at surgery, whether epididymal obstruction is present, and surgical technique. Although vasovasostomy can be performed without an operating microscope, microsurgical technique generally yields superior results.35 Accurate performance of vasoepididymostomy without microsurgery would be essentially impossible.

Pregnancy rates for vasovasostomy and vasoepididymostomy range from 46% to 82% and 27% to 49%, respectively27,33,36–48 (Tables 53-1 and 53-2). Pregnancy rates depend on the above variables as well as female factors and other factors such as antisperm antibodies.

In the study by the Vasovasostomy Study Group, a group of experienced microsurgeons examined the effect of obstructive interval and vasal fluid quality on patency and pregnancy rates. They clearly demonstrated that patency and pregnancy rates were inversely related to the obstructive interval. Patency and pregnancy rates were 97% and 76%, respectively, for obstructive intervals of 3 years or less, 88% and 53% for 3 to 8 years, 76% and 44% for 9 to 14 years, and 71% and 31% for 15 years or greater.

Vasal fluid quality, both the gross and microscopic appearance, was also an important prognostic factor. The patency and pregnancy rates for grossly clear fluid were 91% and 49%, repectively, for opalescent (cloudy, but thin and watery) fluid 93% and 59%, for thick/creamy fluid 70% and 45%, and for no fluid 88% and 54%. The patency and pregnancy rates were 94% and 63%, repectively, if motile sperm were present, 90% and 54% for nonmotile sperm, 96% and 50% for mostly sperm heads but some with tails, 75% and 40% for sperm heads only, and 60% and 31% if sperm were absent. Thus, the absence of sperm in the vasal fluid significantly lowers the success rate, but patency and pregnancy can still occur.33

If sperm are absent from the vasal fluid, epididymal obstruction may be present. Some investigators therefore recommend vasoepididymostomy if sperm are absent from the vas fluid, regardless of other factors. In a series of 44 patients with intravasal azoospermia, all patients remained azoospermic postoperatively. It was concluded that vasoepididymostomy should be performed if sperm are absent from the vas fluid.40 In the Vasovasostomy Study Group, the patency and pregnancy rates if sperm were absent in the vas fluid were 60% and 31%, respectively. Because epididymal obstruction is more likely to occur as the obstructive interval increases and thicker vasal fluid is more suggestive of epididymal obstruction, it is possible to apply vasoepididymostomy selectively and still obtain acceptable results. The Vasovasostomy Study Group recommended that vasoepididymostomy be considered if there was thick pasty fluid without sperm and the obstructive interval was 9 years or more.33 In another study, Kolettis and colleagues found that if vasovasostomy were applied in instances of intravasal azoospermia where the obstructive interval was 11 years or less, the patency and pregnancy rates were 80% and 38%, respectively, similar to those for vasoepididymostomy.49

TREATMENT OF OTHER FORMS OF OBSTRUCTION

Epididymal Obstruction

Epididymal obstruction can occur secondary to inspissated secretions in men with Young’s syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by a combination of obstructive azoospermia and chronic sinopulmonary infections in men without cystic fibrosis.10

If epididymal obstruction is suspected based on these clinical clues, the patient should be scheduled for testis biopsy, vasography, and possible bilateral vasoepididymostomy, all of which can be done at the same time. In these cases, the testis biopsy will document normal spermatogenesis. An intraoperative wet preparation of the biopsy will demonstrate the presence of significant numbers of sperm.50 Permanent pathology is required to document the pattern of sperm production. After vasography, a vasoepididymostomy can be performed. If the patient desires, simultaneous sperm retrieval can be carried out at the same time.

Ejaculatory Duct Obstruction

Men with low-volume azoospermia, a normal FSH level, and at least one palpable vas deferens should undergo transrectal ultrasound to evaluate for ejaculatory duct obstruction. A seminal vesicle diameter of 1.5cm or greater suggests ejaculatory duct obstruction, although there is no definitive threshold for making the diagnosis.7,10 A testis biopsy is then performed and can be examined intraoperatively to document normal spermatogenesis.

Vasogram

Radiographic confirmation of ejaculatory duct obstruction is traditionally documented with a vasogram. The characteristic finding of ejaculatory duct obstruction is a somewhat dilated vasal lumen with abrupt cessation of the contrast at the ejaculatory ducts without filling of the bladder. If a hemivasotomy technique is used, then the vas deferens should be closed after the ejaculatory duct resection with microsurgical technique with either a formal two-layer or modified one-layer technique.51

Seminal Vesiculography

An alternative method for documentation of ejaculatory duct obstruction is seminal vesiculography, as described by Jarow.46 This approach is familiar to most urologists because it is used for prostate biopsies, a commonly performed office procedure.

The seminal vesicle is accessed with transrectal ultrasound. The seminal vesicles can be aspirated, and presence of sperm in the seminal vesicles in an azoospermic man confirms ejaculatory duct obstruction. Once the seminal vesicle is entered, contrast medium is injected and a plain film is obtained. If ejaculatory duct obstruction is present, the contrast will stop abruptly at the level of the ejaculatory ducts and the bladder will not be visualized.52

Transurethral Resection of the Ejaculatory Ducts

If ejaculatory duct obstruction is suspected preoperatively, then the biopsy, vasography (or seminal vesiculography), and ejaculatory duct resection can all be performed at the same time. Preoperative preparation for transurethral resection of the ejaculatory ducts should include broad-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis to cover urinary and fecal flora and a cleansing enema.24

Once the diagnosis of ejaculatory duct obstruction is confirmed with vasography or seminal vesiculography, the patient should be positioned in the lithotomy position. The resectoscope is then inserted into the urethra and a limited resection just lateral to the verumontanum is performed with cutting current to unroof the ejaculatory ducts.24 Once the ejaculatory duct is entered, there should be a significant efflux or “gush” of fluid. Confirmation of successful unroofing of the ducts can be facilitated by injection of either methylene blue or indigo carmine through the vasogram site. In this way, when the ejaculatory duct is entered, blue efflux confirms adequacy of the resection. A Foley catheter is placed and removed the next day if the urine is clear.51

Secondary epididymal obstruction can also occur with ejaculatory duct obstruction. The vasal fluid can be examined at the time of vasography. If no sperm are present then secondary epididymal obstruction may also exist. With this scenario, then, correction of the underlying problem would require two procedures: transurethral resection of the ejaculatory ducts with subsequent vasoepididymostomy, further decreasing the chance for success.24

Potential complications include bladder neck, sphincter, or rectal injury. Retrograde ejaculation and epididymitis can also occur. Finally, men can experience significant urinary and ejaculatory symptoms secondary to urinary reflux into the vasa.10,51

Success Rates

The patency rate (sperm returning to the semen) for transurethral resection of the ejaculatory ducts is approximately 50% and the pregnancy rate is approximately 25%.51 Complications are unusual but can be significant.

Alternative Procedures

An alternative to transurethral resection of the ejaculatory ducts is balloon dilation of the ejaculatory ducts, carried out via a transrectal approach at the time of seminal vesiculography.51,52 Another alternative to surgical correction of ejaculatory duct obstruction is to circumvent the problem with sperm retrieval and ICSI. With improvement in success rates with ICSI, the chance for pregnancy may be better with this approach.

VARICOCELE

A varicocele is the most common identified abnormality noted in a male infertility evaluation, detected in approximately 40% of infertile men.7,53,54 Up to 80% of men with secondary infertility are diagnosed with a varicocele.55 Not all varicoceles cause infertility, however, because 15% of fertile men are found to have a varicocele.53

Pathophysiology

Varicoceles are graded I through III: Grade I: palpable with Valsalva manuever; grade II: palpable; and grade III: visible through the scrotal skin.56 Men with a varicocele that does not drain in the supine position, one that appears suddenly, or an isolated right-sided varicocele should have abdominal imaging to evaluate for a retroperitoneal mass causing obstruction of the renal vein or vena cava.

In the past, it was felt that varicocele size was not important; that is, small varicoceles were considered just as detrimental as large varicoceles. This led to the concept of a subclinical varicocele; that is, one that can be detected by ultrasound but not by physical examination. More recent data suggest that larger varicoceles are more detrimental than small varicoceles.57 Currently, most investigators do not believe that subclinical varicoceles are significant lesions.7

Indication for Repair

A man with a varicocele who is not attempting a pregnancy but desires to do so in the future represents somewhat of a dilemma. Without having attempted a pregnancy a judgment about his fertility status cannot be made. Even if a semen analysis shows some abnormal parameters, he still may be fertile. Even though there is some evidence that a varicocele can cause deterioration in semen parameters over time, most men with a varicocele are not infertile.58 Despite this, varicocele correction in this setting is reasonable because it can eliminate this as a potential source of infertility in the future. For these reasons, many men with a varicocele who desire fertility in the future elect to have their varicocele corrected.

An azoospermic man with a varicocele is problematic. Previous studies demonstrated that about half of the men who underwent repair had motile sperm return to the semen, but natural pregnancies were exceedingly rare.59–61 Thus, the rationale for varicocele correction was to avoid testicular sperm extraction (TESE) and the potential associated complications. Furthermore, some of these men did not have a testis biopsy to rule out excurrent duct obstruction.

More recently, a study by Schlegel and coworkers questioned the benefit of varicocele correction in men with nonobstructive azoospermia. At some point postoperatively, 22% of men had sperm on one semen analysis. Only 10% of the men had sufficient motile sperm in the semen for ICSI, and those men who underwent varicocele ligation did not have any greater success rate for sperm retrieval. Thus, this most recent study suggests the value of varicocele ligation for men with nonobstructive azoospermia is limited.62

Surgical and Nonsurgical Correction

The microsurgical subinguinal approach has continued to gain popularity.63 This approach can be performed with local anesthesia and allows for isolation of the spermatic cord without opening the external oblique fascia. By not opening the fascia, recovery is quicker and pain is reduced.64 A small transverse incision is made in the groin at or just below the external ring. Scarpa’s fascia is opened and the cord is mobilized free. All visible internal spermatic veins are ligated. The testicular arterial branches, lymphatics, and vasal veins are spared.65 Microsurgical technique facilitates the identification of all veins and sparing of the testicular arterial branches and lymphatics.

The inguinal approach is most familiar to most urologists. With this approach, an inguinal incision is made down to the external oblique fascia. The fascia is opened in the direction of its fibers and cord is mobilized free. Then all visible veins are ligated. Magnification is useful with this approach because it can facilitate sparing the artery. Some surgeons also use an operating microscope for this approach as well.53 For the subinguinal and inguinal approaches, the use of papaverine, a vasodilator, and a Doppler aid in the identification of the arterial branches.

The retroperitoneal or high ligation, or Palomo procedure, involves ligation of the entire cord minus the vas deferens. The incision is made above the internal ring and the cord is ligated proximal to the point where the vas turns medially. Thus, the testicular artery is also ligated during this procedure.65 The remaining arterial supply to the testis comes from the vasal artery and cremasterics. The laparoscopic approach is performed transperitoneally, either with or without sparing of the artery. The most popular nonsurgical approach is radiographic embolization. This is usually performed with a femoral vein puncture with passage of an angiographic catheter up the vena cava, across the left renal vein, and then down the gonadal vein. Then, either coils are placed or alcohol is injected to occlude the veins. In experienced hands, embolization has success rates comparable to surgery.66

Each approach to varicocele ligation has its advantages and disadvantages. The subinguinal approach causes less pain because the external oblique fascia is not opened, allowing for a faster recovery.64 At this level, more veins are encountered and the veins may be smaller, necessitating microsurgery. For these reasons, the operative time may be longer than the inguinal approach. The inguinal approach is faster and more familiar to most urologists and fewer veins are encountered. The retroperitoneal approach is fast but is an unfamiliar approach for most urologists. The recurrence rate may be higher because perforating branches may exit the spermatic cord closer to the testis.24,53 Although there does not appear to be an increased incidence of testicular atrophy with this approach, one could question the intentional ligation of the testicular artery during a fertility procedure.

Embolization is advantageous because it does not require general anesthesia or an incision. It also eliminates the risk of arterial injury. It requires an interventional radiologist with specialized skills and involves manipulation of some major vascular structures. Other risks include radiation exposure, intravenous contrast reactions, and coil migration.66

Success Rates

Varicocele treatment is a controversial area in the field of male infertility. Pooled results of several studies demonstrated about a 66% improvement in semen parameters (the definition of improvement can vary between different studies) and a 43% pregnancy rate.56 Controlled studies have yielded conflicting results. A study by Nieschlag and colleagues showed no improvement in pregnancy rates when couples received counseling versus varicocele correction. There are several criticisms of this study. More than half of the couples did not complete the study. The control group was not a true untreated control group in that female factors were optimized and the control group received counseling. Finally, the treatment group actually had a significant improvement in sperm concentration.67 A study by Madgar and colleagues demonstrated that there was a significant difference between varicocele ligation and observation. At 1 year, the treatment group had a pregnancy rate of 60% and the control group had a pregnancy rate of 10%. When the control group was crossed over to treatment their pregnancy rate was 44%. The main criticism of this study is the small number of patients, with only 35 couples studied.65

Complications and Recurrence Rates

Complications of varicocele ligation are rare. The most feared complication is injury to the testicular artery with subsequent atrophy. Testicular atrophy is not inevitable, however, after testicular artery injury. In one large series, the incidence of arterial injury was 0.9%, but there were no cases of testicular atrophy.68 Another complication is hydrocele, which presumably results from lymphatic injury. The incidence is about 7% and is probably less common with microsurgical technique.53 Finally, varicoceles can recur or persist in 10% or less of cases after treatment.

SPERM RETRIEVAL TECHNIQUES

When considering sperm retrieval, the most important distinction to be made is between obstructive and nonobstructive azoospermia. Patients with nonobstructive azoospermia have decreased or absent sperm production with a patent ductal system; patients with obstructive azoospermia have normal sperm production and an obstruction at some point distal to the testis. In obstructive azoospermia, sperm retrieval is essentially 100% successful. Also, with obstructive azoospermia, percutaneous office procedures can retrieve sperm with high rates of success, whereas these procedures are not as successful in patients with nonobstructive azoospermia.

Obstructive Azoospermia

If sperm retrieval is being performed for men with cystic fibrosis or congenital absence of the vas deferens, then the man and his partner should be tested for cystic fibrosis and the intron-8 poly(T) variant, and appropriate genetic counseling should be provided.69,70

Microepididymal Sperm Aspiration

With MESA, the greatest numbers of sperm are retrieved and the sperm are easiest to process and cryopreserve.71 It is usually possible to obtain multiple vials for cryopreservation.

Cryopreservation of epididymal sperm does not appear to compromise pregnancy rates with ICSI.72 Because cryopreservation is virtually always possible with MESA samples, the chance that a patient will require a repeat procedure is significantly reduced. This technique, however, is the most invasive and the most expensive and requires microsurgical skills.

Percutaneous Epididymal Sperm Aspiration

In general, fewer sperm are retrieved and cryopreservation is therefore more difficult.71 Because it is a blind procedure, there is potential for injury to the epididymis that could compromise future attempts at microsurgical reconstruction. If no sperm can be obtained from either epididymis, then percutaneous testicular sperm aspiration can be performed.

Testicular Sperm Aspiration

The testis is isolated and local anesthetic is administered. Then a fine-gauge butterfly needle is passed percutaneously into the testis. Negative pressure is employed by pulling back on the syringe handle attached to the needle. Use of a Cameco syringe is also helpful in TESA.73 Because of the intratesticular arterial anatomy, it is safest to aspirate from the medial or lateral aspect of the upper pole of the testis.18

Nonobstructive Azoospermia

Although there are isolated reports of successful sperm retrieval with percutaneous techniques, most comparative studies demonstrate superior sperm retrieval rates with open techniques for men with nonobstructive azoospermia.74,75 Before attempting sperm retrieval, it is critical that the man have a thorough clinical and genetic evaluation. All men with nonobstructive azoospermia who are pursuing sperm retrieval should have a karyotype performed. If an abnormality is detected, he and his partner should receive genetic counseling before attempting sperm retrieval.69

Testing for Y chromosome microdeletion is also important, because the results can help predict successful sperm retrieval. In one study, no man with AZFa or AZFb deletions had sperm retrieved from the testes. In contrast, those azoospermic men with AZFc deletions had a 75% chance for successful sperm retrieval.76 Another study also suggested that the type of AZF deletion was important in predicting successful sperm retrieval.77 Standard clinical parameters (i.e., testis size, FSH level) cannot predict success or failure with sperm retrieval.78

Sperm production in nonobstructive azoospermia is usually heterogeneous and may be found only in isolated locations or “pockets” of spermatogenesis. As such, sperm retrieval in nonobstructive azoospermia typically requires multiple biopsies and frequently bilateral biopsies for adequate sampling. Sperm retrieval rates in nonobstructive azoospermia are as high as 77%, but most series demonstrate success rates of approximately 50%.10 Multiple biopsies carry some risk of testicular injury. Two techniques have been recently devised to improve success rates for sperm retrieval in nonobstructive azoospermia and limit the amount of testicular tissue removed.

Surgical Techniques

Testicular Sperm Extraction

In the technique of Turek, fine-needle mapping is performed. Percutaneous fine-needle aspirations are performed from different regions of the testis to create a “map.” Then at the time of TESE, those regions where sperm were detected are explored and sampled with open biopsies. In a small series of patients, the sperm retrieval rate was 95% (20/21).79

Microdissection

A second technique, microdissection, was introduced by Schlegel. In this procedure, the tunica albuginea is widely opened to expose the testicular parenchyma. Using the operating microscope, a search is carried out for visibly dilated tubules because these are more likely to contain sperm. These areas are sampled and analyzed intraoperatively (Fig. 53-4).80 Collapsed, sclerotic tubules are not sampled. With this technique, a sperm retrieval rate of 63% was obtained and less testicular tissue was removed.81

1 Sigman M, Lipshultz LI, Howards SS. Evaluation of the subfertile male. In: Lipshultz LI, Howards SS, editors. Infertility in the Male. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997:173-193.

2 Pavlovich CP, Schlegel PN. Fertility options after vasectomy: A cost-effectiveness analysis. Fertil Steril. 1997;67:133-141.

3 Kolettis PN, Thomas AJJr. Vasoepididymostomy for vasectomy reversal: A critical assessment in the era of intracytoplasmic sperm injection. J Urol. 1997;158:467-470.

4 Schlegel PN. Is assisted reproduction the optimal treatment for varicocele-associated male infertility? A cost-effectiveness analysis. Urol. 1997;49:83-90.

5 Honig SC, Lipshultz LI, Jarow J. Significant medical pathology uncovered by a comprehensive male infertility evaluation. Fertil Steril. 1994;62:1028-1034.

6 Kolettis PN, Sabanegh ES. Significant medical pathology discovered during a male infertility evaluation. J Urol. 2001;166:178-180.

7 Sigman M, Jarow JP. Male infertility. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan ED, Wein AJ, editors. Campbell’s Urology. 8th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2002:1475-1531.

8 Meacham RB, Hellerstein DK, Lipshultz LI. Evaluation and treatment of ejaculatory duct obstruction in the infertile male. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:393-397.

9 Pryor JP, Hendry WF. Ejaculatory duct obstruction in subfertile males: Analysis of 87 patients. Fertil Steril. 1991;56:725-730.

10 Kolettis PN. The evaluation and management of the azoospermic patient. J Androl. 2002;23:293-305.

11 Coburn M, Kim ED, Wheeler TM. Testicular biopsy in male infertility evaluation. In: Lipshultz LI, Howards SS, editors. Infertility in the Male. 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1997:219-248.

12 Nagler HM, Thomas AJJr. Testicular biopsy and vasography in the evaluation of male infertility. Urol Clin North Am. 1987;14:167-176.

13 Jaffe TM, Kim ED, Hoekstra TH, Lipshultz LI. Sperm pellet analysis: A technique to detect the presence of sperm in men considered to have azoospermia by routine semen analysis. J Urol. 1998;159:1548-1550.

14 Levin HS. Nonneoplastic diseases of the testis. In: Sternberg S, editor. Diagnostic Surgical Pathology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 1999:1943-1971.

15 Silber SJ, Rodriguez-Rigau LJ. Quantitative analysis of testicle biopsy: Determination of partial obstruction and prediction of sperm count after surgery for obstruction. Fertil Steril. 1981;4:480-485.

16 Harrington TG, Schauer D, Gilbert BR. Percutaneous testis biopsy: An alternative to open testicular biopsy in the evaluation of the subfertile man. J Urol. 1996;156:1647-1651.

17 Rosenlund B, Kvist U, Ploen L, et al. Comparison between open and percutaneous needle biopsies in men with azoospermia. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:1266-1271.

18 Jarow JP. Clinical significance of intratesticular arterial anatomy. J Urol. 1991;145:777-779.

19 Plas E, Riedl CR, Engelhardt PF, et al. Unilateral or bilateral testicular biopsy in the era of intracytoplasmic sperm injection. J Urol. 1999;162:2010-2013.

20 Poore RE, Schneider A, DeFranzo AJ, et al. Comparison of puncture versus vasotomy techniques for vasography in an animal model. J Urol. 1997;158:464-466.

21 Sheynkin YR, Hendin BN, Schlegel PN, Goldstein M. Microsurgical repair of iatrogenic injury to the vas deferens. J Urol. 1998;159:139-141.

22 Handelsman DJ. Obstructive azoospermia after a second renal transplant: An avoidable cause of infertility. Aust NZ J Med. 1984;14:155-156.

23 Uzzo RG, Lemack GE, Morrissey MM, Goldstein M. The effects of Marlex mesh on the spermatic cord. J Urol. 1997;157(4Suppl):302.

24 Goldstein M. Surgical management of male infertility and other scrotal disorders. In: Walsh PC, Retik AB, Vaughan ED, et al, editors. Campbell’s Urology. 7th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 1998:1331-1377.

25 Silber SJ. Epididymal extravasation following vasectomy as a cause for failure of vasectomy reversal. Fertil Steril. 1979;31:309-315.

26 Sharlip ID. Microsurgical vasovasostomy. In: Thomas AJ, Nagler HM, editors. Atlas of Surgical Management of Male Infertility. New York: Igaku Shoin; 1995:58-59.

27 Thomas AJ, Howards SS. Microsurgical treatment of male infertility. In: Lipshultz LI, Howards SS, editors. Infertility in the Male. 3rd ed. St Louis: Mosby; 1997:371-384.

28 Thomas AJ. Vasoepididymostomy. In: Thomas AJ, Nagler HM, editors. Atlas of Surgical Management of Male Infertility. New York: Igaku Shoin; 1995:67.

29 Thomas AJJr. Vasoepididymostomy. Urol Clin N Amer. 1987;14:527-538.

30 Berger RE. Triangulation end to side vasoepididymostomy. Urol. 1998;159:1951-1953.

31 Marmar JL. Modified vasoepididymostomy with simultaneous double needle placement, tubulotomy, and tubular invagination. J Urol. 2000;163:483-486.

32 Matthews GJ, Schlegel PN, Goldstein M. Patency following microsurgical vasoepididymostomy and vasovasostomy: Temporal considerations. J Urol. 1995;154:2070-2073.

33 Belker AM, Thomas AJJr, Fuchs EF, et al. Results of 1,469 microsurgical vasectomy reversals by the Vasovasostomy Study Group. J Urol. 1991;145:505-511.

34 Belker AM, Fuchs EF, Konnak JW, et al. Transient fertility after vasovasostomy in 892 patients. J Urol. 1985;134:75-76.

35 Middleton RG, Belker AM. Macrosurgery or microsurgery for vasovasostomy? Cont Urol. 1995:55-60.

36 Cos LR, Valvo JR, Davis RS, Cockett AT. Vasovasostomy: Current state of the art. Urolology. 1983;22:567-575.

37 Requeda E. Fertilizing capacity and sperm antibodies in vasovasostomized men. Fertil Steril. 1983;39:197-203.

38 Owen E, Kapila H. Vasectomy reversal Review of 475 microsurgical vasovasostomies. Med J Aust. 1984;140:398-400.

39 Lee HY. A 2-year experience with vasovasostomy. J Urol. 1986;136:413-415.

40 Silber SJ. Pregnancy after vasovasostomy for vasectomy reversal: A study of factors affecting long-term return of fertility in 282 patients followed for 10 years. Hum Reprod. 1989;4:318-322.

41 Fox M. Vasectomy reversal–microsurgery for best results. Br J Urol. 1994;73:449-453.

42 Fogdestam I, Fall M, Nilsson S. Microsurgical epididymovasostomy in the treatment of occlusive azoospermia. Fertil Steril. 1986;46:925-929.

43 Silber SJ. Results of microsurgical vasoepididymostomy: Role of epididymis in sperm maturation. Hum Reprod. 1989;4:298-303.

44 Schlegel PN, Goldstein M. Microsurgical vasoepididymostomy: Refinements and results. J Urol. 1993;150:1165-1168.

45 Matsuda T, Horii Y, Muguruma K, et al. Microsurgical epididymovasostomy for obstructive azoospermia: Factors affecting postoperative fertility. Eur Urol. 1994;26:322-326.

46 Jarow JP, Oates RD, Buch JP, et al. Effect of level of anastomosis and quality of intraepididymal sperm on the outcome of end-to-side epididymovasostomy. Urolology. 1997;49:590-595.

47 Takihara H. The treatment of obstructive azoospermia in male infertility—past present and future. Urolology. 1998;51(Suppl 5A):150-155.

48 Kim ED, Winkel E, Orejuela F, Lipshultz LI. Pathological epididymal obstruction unrelated to vasectomy: Results with microsurgical reconstruction. J Urol. 1998;160:2078-2080.

49 Kolettis PN, D’Amico AM, Box LC, Burns JR. Outcomes for vasovasostomy with bilateral intravasal azoospermia. J Androl. 2003;24:22-24.

50 Belker AM, Sherins RJ, Dennison-Lagos L. Simple, rapid staining method for immediate intraoperative examination of testicular biopsies. J Androl. 1996;17:420-426.

51 Schlegel PN. Management of ejaculatory duct obstruction. In: Lipshultz LI, Howards SS, editors. Infertility in the Male. 3rd ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 1997:385-394.

52 Jones TR, Zagoria RJ, Jarow JP. Transrectal US-guided seminal vesiculography. Radiology. 1997;205:276-278.

53 Goldstein M, Gilbert BR, Dicker AP, et al. Microsurgical inguinal varicocelectomy with delivery of the testis: An artery and lymphatic sparing technique. J Urol. 1992;148:1808-1811.

54 World Health Organization. The influence of varicocele on parameters of fertility in a large group of men presenting to infertility clinics. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:1289-1293.

55 Gorelick JI, Goldstein M. Loss of fertility in men with varicocele. Fertil Steril. 1993;59:613-616.

56 Pryor JL, Howard SS. Varicocele. Urol Clin North Am. 1987;14:499-513.

57 Steckel J, Dicker AP, Goldstein M. Relationship between varicocele size and response to varicocelectomy. J Urol. 1993;149:769-771.

58 Chehval MJ, Purcell MH. Deterioration of semen parameters over time in men with untreated varicocele: Evidence of progressive testicular damage. Fertil Steril. 1992;57:174-177.

59 Matthews GJ, Matthews ED, Goldstein M. Induction of spermatogenesis and achievement of pregnancy after microsurgical varicocelectomy in men with azoospermia and severe oligoasthenospermia. Fertil Steril. 1998;70:71-75.

60 Kim ED, Leibman BB, Grinblat DM, Lipshultz LI. Varicocele repair improves semen parameters in azoospermic men with spermatogenic failure. J Urol. 1999;162:737-740.

61 Pasqualotto FF, Lucon AM, Hallak J, et al. Induction of spermatogenesis in azoospermic men after varicocele repair. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:108-112.

62 Schlegel PN, Kaufmann J. Role of varicocelectomy in men with nonobstructive azoospermia. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:1585-1588.

63 Marmar JL, DeBenedictis TJ, Praiss D. The management of varicoceles by microdissection of the spermatic cord at the external inguinal ring. Fertil Steril. 1985;43:583-588.

64 Enquist E, Stein BS, Sigman M. Laparoscopic versus subinguinal varicocelectomy: A comparative study. Fertil Steril. 1994;61:1092-1096.

65 Madgar I, Karasik A, Weissenberg R, et al. Controlled trial of high spermatic vein ligation for varicocele in infertile men. Fertil Steril. 1995;63:120-124.

66 Dewire DM, Thomas AJJr, Falk RM, et al. Clinical outcome and cost comparison of percutaneous embolization and surgical ligation of varicocele. J Androl. 1994;15(Suppl):38S-42S.

67 Nieschlag E, Hertle L, Fischedick A, et al. Update on treatment of varicocele: Counseling as effective as occlusion of the vena spermatica. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:2147-2150.

68 Chan PT, Wright EJ, Goldstein M. Incidence and post-operative outcomes of accidental ligation of the testicular artery during microsurgical varicocelectomy. Fertil Steril. 2001;76(3Suppl 1):S49.

69 Van Assche E, Bonduelle M, Tournaye H, et al. Cytogenetics of infertile men. Hum Reprod. 1996;11(Suppl 4):1-26.

70 Anguiano A, Oates RD, Amos JA, et al. Congenital bilateral absence of the vas deferens. A primarily genital form of cystic fibrosis. JAMA. 1992;267:1794-1797.

71 Sheynkin YR, Ye Z, Menendez S, et al. Controlled comparison of percutaneous and microsurgical sperm retrieval in men with obstructive azoospermia. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:3086-3089.

72 Tournaye H, Merdad T, Silber S, et al. No differences in outcome after intracytoplasmic sperm injection with fresh or with frozen–thawed epididymal spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:90-95.

73 Belker AM, Sherins RJ, Dennison-Lagos L, et al. Percutaneous testicular sperm aspiration: A convenient and effective office procedure to retrieve sperm for in vitro fertilization with intracytoplasmic sperm injection. J Urol. 1998;160:2058-2062.

74 Ezeh UI, Moore HD, Cooke ID. A prospective study of multiple needle biopsies versus a single open biopsy for testicular sperm extraction in men with non-obstructive azoospermia. Hum Reprod. 1998;13:3075-3080.

75 Friedler S, Raziel A, Strassburger D, et al. Testicular sperm retrieval by percutaneous fine needle sperm aspiration compared with testicular sperm extraction by open biopsy in men with non-obstructive azoospermia. Hum Reprod. 1997;12:1488-1493.

76 Hopps CV, Mielnik A, Goldstein M, et al. Detection of sperm in men with Y chromosome microdeletions of the AZFa, AZFb and AZFc regions. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:1660-1665.

77 Vogt PH, Edelmann A, Kirsch S, et al. Human Y chromosome azoospermia factors (AZF) mapped to different subregions in Yq11. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:933-943.

78 Tournaye H, Verheyen G, Nagy P, et al. Are there any predictive factors for successful testicular sperm recovery in azoospermic patients? Hum Reprod. 1997;12:80-86.

79 Turek PJ, Givens CR, Schriock ED, et al. Testis sperm extraction and intracytoplasmic sperm injection guided by prior fine-needle aspiration mapping in patients with nonobstructive azoospermia. Fertil Steril. 1999;71:552-557.

80 Schlegel PN, Hopps CV. Evaluation of the male in infertility. In: Sciarra JJ, editor. Gynecology & Obstetrics. Chicago: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2002:365-401.

81 Schlegel PN. Testicular sperm extraction: Microdissection improves sperm yield with minimal tissue excision. Hum Reprod. 1999;14:131-135.