Chapter 430 Sudden Death

Sudden death other than sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS; Chapter 367) is rare in children younger than 18 yr. Sudden death can be divided into either traumatic or nontraumatic origin. Traumatic causes of sudden death are the most common in children; these include motor vehicle crashes, violent deaths, recreational deaths, and occupational deaths. Nontraumatic sudden deaths are often due to specific cardiac causes. The incidence of sudden death varies from 0.8 to 6.2 per 100,000 per year in children and adolescents as opposed to the higher incidence of sudden cardiac death in adults of 1 per 1,000. Approximately 65% of sudden deaths are due to heart-related problems in patients with either normal or congenitally (corrected, palliated, or unoperated) abnormal hearts. Competitive high-school sports (basketball, football) are high-risk environmental factors. The most common cause of death in competitive athletes is hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, with or without obstruction to left ventricular outflow. Other potential causes are listed in Table 430-1. These can be classified as structural abnormalities, including aortic stenosis and coronary artery abnormalities; myocardial disease, such as myocarditis; conduction system disease, including long Q-T syndrome (LQTS); and miscellaneous causes, including pulmonary hypertension and commotio cordis. Symptoms may be absent before the event but, if present, include syncope, chest pain, dyspnea, and palpitations. Patients may have a family history of heart disease (dilated or hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, long Q-T interval, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, Marfan syndrome) or sudden death. Death often follows exertion or exercise.

Table 430-1 POTENTIAL CAUSES OF SUDDEN DEATH IN INFANTS, CHILDREN, AND ADOLESCENTS

SIDS AND SIDS “MIMICS”

CORRECTED OR UNOPERATED CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE

CORONARY ARTERIAL DISEASE

MYOCARDIAL DISEASE

CONDUCTION SYSTEM ABNORMALITY/ARRHYTHMIA

MISCELLANEOUS

SIDS, sudden infant death syndrome.

Mechanism of Sudden Death

There are 3 mechanisms of sudden death: arrhythmic, nonarrhythmic cardiac (circulatory and vascular causes), and noncardiac. Ventricular fibrillation (VF), while the most common final cause of sudden death in adults, is only the final cause in 10-20% of children with sudden cardiac death. More commonly, bradycardia leads either to VF or asystole (Chapter 429).

Congenital Heart Disease

Valvar aortic stenosis is the congenital defect most commonly associated with sudden death in children. Historically, approximately 5% of children with this disease die. A history of syncope, chest pain, and evidence of severe obstruction and left ventricular hypertrophy are risk factors (Chapter 421.5).

Cardiomyopathy

All 3 major types of cardiomyopathy (hypertrophic, dilated, and restrictive) are associated with sudden death in the pediatric population; sudden death may be the initial manifestation of the cardiomyopathy (Chapter 433).

Cardiac Arrhythmia

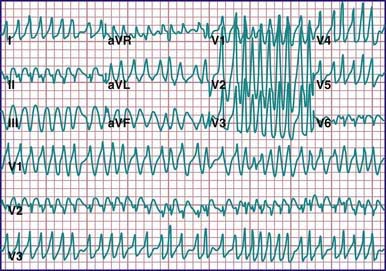

A primary conduction system abnormality may result in sudden death. Causes include Wolff-Parkinson-White (WPW) syndrome and long Q-T syndrome. Besides causing supraventricular tachycardia (SVT), WPW syndrome can result in atrial fibrillation with rapid conduction across the accessory pathway leading to ventricular fibrillation and sudden death (Fig. 430-1) (Chapter 429). This is unusual in pediatric patients but has an increasing incidence in adolescence. In adults, there is an incidence of sudden death in asymptomatic patients of 1 per 1,000 patient-years, but this rate may well be higher in children, who by definition have not survived to adulthood. As digoxin and verapamil can augment conduction down accessory pathways, these drugs are contraindicated in WPW syndrome.

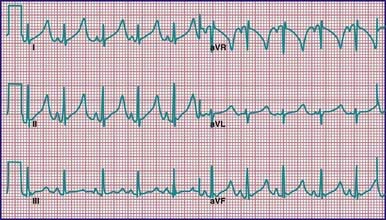

Long Q-T syndrome (Chapter 429), a group of channelopathies that affect ventricular repolarization, is also associated with sudden death (Fig. 430-2). The mechanism of sudden death is polymorphic VT (torsades de pointes) (Fig. 430-3). An initial presentation of sudden cardiac death is found in 9% of patients. Thus, treatment of asymptomatic patients with a long Q-T interval on electrocardiogram (ECG) and positive family history is advised.

Figure 430-2 Long Q-T syndrome in a neonate. QTc is markedly prolonged. T waves are also peaked and abnormal in appearance.

Acquired long Q-T intervals may be seen in patients with marked electrolyte abnormalities, CNS injury, or starvation (including bulimia and anorexia nervosa). Medications can also result in prolongation of the Q-T interval (Table 429-4). These patients are also at risk of malignant ventricular arrhythmias, and correction of the underlying problem may be necessary to reduce the risk of sudden death.

Prevention of Sudden Death

Many of the more common causes of sudden death in children and adolescents can be identified from the patient’s history (prodromal symptoms), the family history, and physical examination (Table 430-2). Of paramount importance is the careful evaluation of any child who experiences syncope in association with exercise, as this may be the last opportunity to diagnose a life-threatening condition in such a patient.

Table 430-2 CARDIAC SCREENING QUESTIONS INCLUDED IN THE PREPARTICIPATION PHYSICAL EVALUATION

Reprinted with permission from “Preparticipation Physical Evaluation.” Copyright © American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved.

Atkins DL, Everson-Stewart S, Sears GK, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in children. Circulation. 2009;119:1484-1491.

Atkins DL, Kenney MA. Automated external defibrillators: safety and efficacy in children and adolescents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:1443-1462.

Baggish AL, Hutter AMJr, Wang F, et al. Cardiovascular screening in college athletes with and without electrocardiography. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:269-275.

Berger S, Kugler JD, Thomas JA, et al. Sudden cardiac death in children and adolescents: introduction and overview. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2004;51:1201-1209.

Burkhardt BEU, Fischer PR, Brands CK, et al. Exercise performance in adolescents with autonomic dysfunction. J Pediatr. 2011;158:28-32.

Chaitman BR, Fromer M. Should ECG be required in young athletes? Lancet. 2008;371:1489-1490.

Chockalingam P, Rammeloo LA, Postema PG, et al. Fever-induced life-threatening arrhythmias in children harboring an SCN5A mutation. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):e239-e244.

Doolan A, Langlois N, Semsarian C. Causes of sudden cardiac death in young Australians. Med J Aust. 2004;180:110-112.

Gould MS, Walsh BT, Munfakh JL, et al. Sudden death and use of stimulant medications in youths. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:992-1001.

Hofman N, Tan HL, Clur SA, et al. Contribution of inherited heart disease to sudden cardiac death in childhood. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e967-e973.

Jarjour IT, Jarjour LK. Low iron storage in children and adolescents with neurally mediated syncope. J Pediatr. 2008;153:40-44.

Kelly J, Kenny D, Martin RP, et al. Diagnosis and management of elite young athletes undergoing arrhythmia intervention. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:21-24.

Kenny D, Martin R. Drowning and sudden cardiac death. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:5-8.

Kumpf M, Sieverding L, Gass M, et al. Anomalous origin of left coronary artery in young athletes with syncope. BMJ. 2006;332:1139-1141.

Lane JR, Ben-Shachar G. Myocardial infarction in healthy adolescents. Pediatrics. 2007;120:e938-e943.

Mahle WT, Campbell RM, Favaloro-Sabatier J. Myocardial infarction in adolescents. J Pediatr. 2007;151:150-154.

Maron BJ, Estes NAMIII. Commotio cordis. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:917-927.

Papadakis M, Sharma S. Electrocardiographic screening in athletes: the time is now for universal screening. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:663-668.

Papadakis M, Whyte G, Sharma S. Preparticipation screening for cardiovascular abnormalities in young competitive athletes. BMJ. 2008;337:806-811.

Pelliccia A, Di Paolo FM, Quattrini FM, et al. Outcomes in athletes with marked ECG repolarization abnormalities. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:152-161.

Plunkett A, Hulse JA, Gill MJ. Variable presentation of Brugada syndrome: lesions from three generations with syncope. Br Med J. 2003;326:1078-1079.

Rausch CM, Phillips GC. Adherence to guidelines for cardiovascular screening in current high school preparticipation evaluation forms. J Pediatr. 2009;155:584-586.

Rowland T. Sudden unexpected death in young athletes: reconsidering “hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.”. Pediatrics. 2009;123:1217-1222.

Sofi F, Capalbo A, Pucci N, et al. Cardiovascular evaluation, including resting and exercise electrocardiography, before participation in competitive sports: cross sectional study. BMJ. 2008;337:88-92.

Steinvil A, Chundadze T, Zeltser D, et al. Mandatory electrocardiographic screening of athletes to reduce their risk for sudden death. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57(11):1291-1296.

Stewart JM. Reduced iron stores and its effect on vasovagal syncope (simple faint). J Pediatr. 2008;153:9-11.

Thompson PD, Levine BD. Protecting athletes from sudden cardiac death. JAMA. 2006;296:1648-1650.

Weinstock J, Maron BJ, Song C, et al. Failure of commercially available chest wall protectors to prevent sudden cardiac death induced by chest wall blows in an experimental model of commotio cordis. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e656-e662.

Wheeler MT, Heidenreich PA, Froelicher VF, et al. Cost-effectiveness of preparticipation screening for prevention of sudden cardiac death in young athletes. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:276-286.