Chapter 108 Substance Abuse

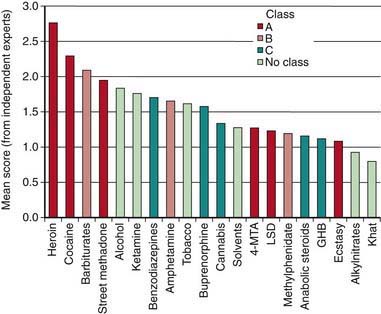

Individuals who initiate drug use at an early age are at a greater risk for becoming addicted than those who try drugs in early adulthood. Drug use in younger, less experienced adolescents can act as a substitute for developing age-appropriate coping strategies and enhance vulnerability to poor decision-making. The first use of the most commonly used drugs occurs before age 18 yr, with 88% of people reporting first alcohol use <21 yr old, the legal drinking age in the USA. Inhalants have been identified as a popular first drug for youth in grade 8. When drug use begins to negatively alter functioning in adolescents at school and at home, and risk-taking behavior is seen, intervention is warranted. Serious drug use is not an isolated phenomenon. It occurs across every segment of the population and is one of the most challenging public health problems facing society. The challenge to the clinician is to identify youths at risk for substance abuse and offer early intervention. The challenge to the community and society is to create norms that decrease the likelihood of adverse health outcomes for adolescents and promote and facilitate opportunities for adolescents to choose healthier and safer options. Recognizing those drugs with the greatest harm, and at times focusing on harm reduction with or without abstinence, is an important modern approach to adolescent substance abuse (Figs. 108-1, 108-2).

Figure 108-2 Protection and risk model for distal and proximal determinants of risky substance use and related harms.

(From Toumbourou JW, Stockwell T, Neighbors C, et al: Interventions to reduce harm associated with adolescent substance use, Lancet 369:1391–1401, 2007.)

Etiology

Substance abuse is biopsychosocially determined (see Fig. 108-2). Biologic factors, including genetic predisposition, are established contributors. Behaviors such as rebelliousness, poor school performance, delinquency, and criminal activity and personality traits such as low self-esteem, anxiety, and lack of self-control are frequently associated with or predate the onset of drug use. Psychiatric disorders are often co-morbidly associated with adolescent substance use. Conduct disorders and antisocial personality disorders are the most common diagnoses coexisting with substance abuse, particularly in males. Teens with depression (Chapter 24), attention deficit disorder (Chapter 30), and eating disorders (Chapter 26) have high rates of substance use. The determinants of adolescent substance use and abuse are explained using a number of theoretical models, with factors at the individual level, the level of significant relationships with others, and the level of the setting or environment. Models include a balance of risk and protective or coping factors that tend to account for individual differences among adolescents with similar risk factors who escape adverse outcomes.

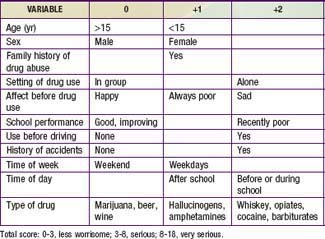

Specific historical questions can assist in determining the severity of the drug problem through a rating system (Table 108-1). The type of drug used (marijuana versus heroin), the circumstances of use (alone or in a group setting), the frequency and timing of use (daily before school versus rarely on a weekend), the premorbid mental health status (depressed versus happy), as well as the teenager’s general functional status should all be considered in evaluating any youngster found to be abusing a drug. The stage of drug use/abuse should also be considered (Table 108-2). A teen may spend months or years in the experimentation phase trying a variety of illicit substances including the most common drugs, cigarettes, alcohol, and marijuana. It is not until regular use of drugs resulting in negative consequences (problem use) that the teen typically become identified as having a problem, either by parents, teachers, or a physician. Certain protective factors play a part in buffering the risk factors as well as assisting in anticipating the long-term outcome of experimentation. Having emotionally supportive parents with open communication styles, involvement in organized school activities, having mentors or role models outside of the home, and recognition of the importance of academic achievement are examples of the important protective factors.

| STAGE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| 1 |

Epidemiology

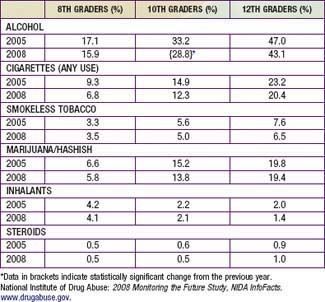

In the USA, alcohol and cigarettes and marijuana are the most commonly reported substances used among teens (Table 108-3). The prevalence of substance use and associated risky behaviors vary by age, gender, race/ethnicity, and other sociodemographic factors. Younger teenagers tend to report less use of drugs than do older teenagers, with the exception of inhalants (in 2008, 15.7% in 8th grade, 12.8% in 10th grade, 9.9% in 12th grade). Males have higher rates of both licit and illicit drug use than females, with greatest differences seen in their higher rates of frequent use of smokeless tobacco, cigars, and anabolic steroids. In school surveys, drug use patterns of Hispanics tend to fall in between whites and African-Americans, with the exception of 12th grade Hispanics reporting highest rates of crack cocaine, heroin (injected), and crystal methamphetamine use. African-Americans report less use of drugs across all drug categories with dramatically lower levels of cigarette use in comparison to whites.

Table 108-3 THIRTY DAY PREVALENCE USE OF ALCOHOL, CIGARETTES, MARIJUANA, AND INHALANTS IN 8TH GRADERS, 10TH GRADERS, AND 12TH GRADERS, 2005 AND 2008

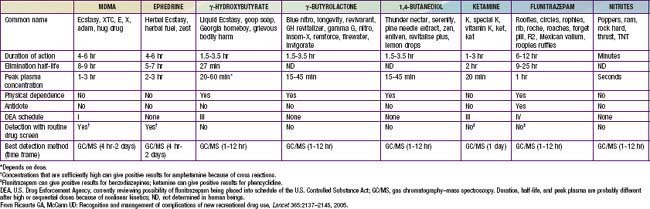

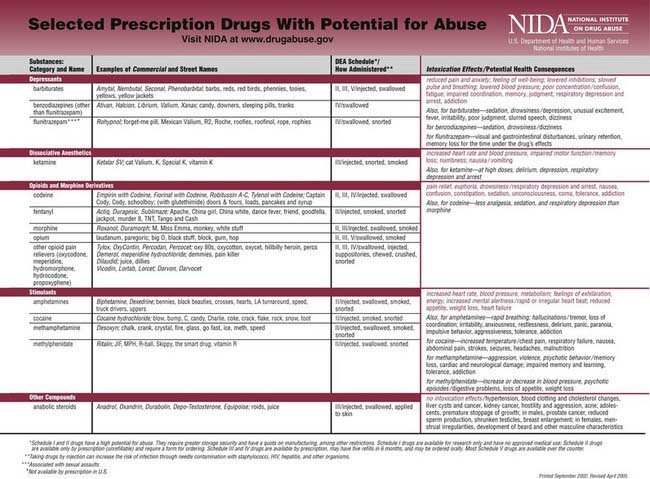

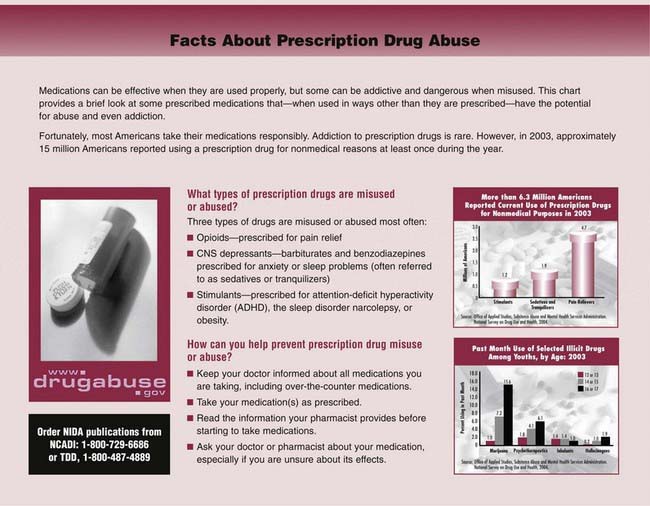

In examining trends in drug use, positive findings are that fewer students reported cigarette, alcohol, or stimulant use than in the previous 5 yr. Marijuana use has leveled off after a general decline. (Past year use of marijuana in 2008: 10.9% in 8th graders, 23.9% in 10th graders, 32.4% in 12th graders.) Prescription drug abuse is increasing in prevalence with 15.4% of high school seniors reported taking a prescription drug nonmedically in the last yr (Table 108-4). For many adolescents and young adults, prescription drug use is the most common abused category of drugs and includes opioids, drugs that treat ADHD, antianxiety agents, dextromethorphan, antihistamines, sedatives, and tranquilizers. Many of these agents can be found in the parents’ home, some are over-the-counter, while others are purchased from drug dealers at schools and colleges. Many users believe that these drugs are benign because they are obtained by prescription or purchased at a pharmacy. Club drugs, commonly used at all-night dance parties, are increasingly popular among older adolescents and young adults (Table 108-5). These drugs have significant side effects especially if taken in combination with alcohol or other drugs. Anterograde amnesia, impaired learning ability, disassociation, and breathing difficulties may occur. Repeated use may lead to tolerance, cravings for the drug, and withdrawal effects including anxiety, tremors, and sweating.

Table 108-4 SELECTED PRESCRIPTION DRUGS WITH POTENTIAL FOR ABUSE

Clinical Manifestations

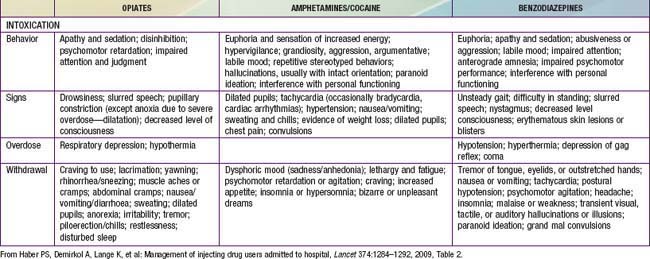

Although manifestations vary by the specific substance of use, adolescents who use drugs often present in an office setting with no obvious physical findings. Drug use is more frequently detected in adolescents who experience trauma such as motor vehicle crashes, bicycle injuries, or violence. Eliciting appropriate historical information regarding substance use, followed by blood alcohol and urine drug screens is recommended in emergency settings. An adolescent presenting to an emergency setting with an impaired sensorium should be evaluated for substance use as a part of the differential diagnosis (Table 108-6). Screening for substance use is recommended for patients with psychiatric and behavioral diagnoses. Other clinical manifestations of substance use are associated with the route of use; intravenous drug use is associated with venous “tracks” and needle marks, while nasal mucosal injuries are associated with nasal insufflation of drugs. Seizures can be a direct effect of drugs such as cocaine and amphetamines or an effect of drug withdrawal in the case of barbiturates or tranquilizers.

| ANTICHOLINERGIC SYNDROMES | |

| Common signs | Delirium with mumbling speech, tachycardia, dry, flushed skin, dilated pupils, myoclonus, slightly elevated temperature, urinary retention, and decreased bowel sounds. Seizures and dysrhythmias may occur in severe cases. |

| Common causes | Antihistamines, antiparkinsonian medication, atropine, scopolamine, amantadine, antipsychotic agents, antidepressant agents, antispasmodic agents, mydriatic agents, skeletal muscle relaxants, and many plants (notably jimson weed and Amanita muscaria). |

| SYMPATHOMIMETIC SYNDROMES | |

| Common signs | Delusions, paranoia, tachycardia (or bradycardia if the drug is a pure α-adrenergic agonist), hypertension, hyperpyrexia, diaphoresis, piloerection, mydriasis, and hyperreflexia. Seizures, hypotension, and dysrhythmias may occur in severe cases. |

| Common causes | Cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine (and its derivatives 3,4-methylenedioxyamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine, 3,4-methylenedioxyethamphetamine, and 2,5-dimethoxy-4-bromoamphetamine), and over-the-counter decongestants (phenylpropanolamine, ephedrine, and pseudoephedrine). In caffeine and theophylline overdoses, similar findings, except for the organic psychiatric signs, result from catecholamine release. |

| OPIATE, SEDATIVE, OR ETHANOL INTOXICATION | |

| Common signs | Coma, respiratory depression, miosis, hypotension, bradycardia, hypothermia, pulmonary edema, decreased bowel sounds, hyporeflexia, and needle marks. Seizures may occur after overdoses of some narcotics, notably propoxyphene. |

| Common causes | Narcotics, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, ethchlorvynol, glutethimide, methyprylon, methaqualone, meprobamate, ethanol, clonidine, and guanabenz. |

| CHOLINERGIC SYNDROMES | |

| Common signs | Confusion, central nervous system depression, weakness, salivation, lacrimation, urinary and fecal incontinence, gastrointestinal cramping, emesis, diaphoresis, muscle fasciculations, pulmonary edema, miosis, bradycardia or tachycardia, and seizures. |

| Common causes | Organophosphate and carbamate insecticides, physostigmine, edrophonium, and some mushrooms. |

From Kulig K: Initial management of ingestions of toxic substances, N Engl J Med 326:1678, 1992.

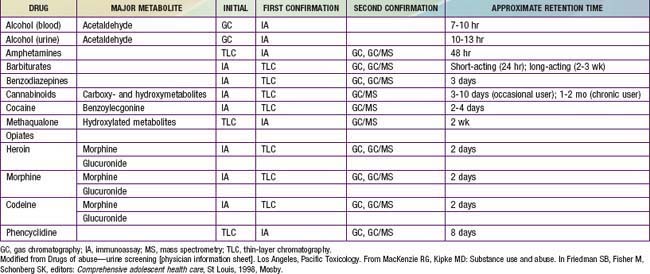

Screening for Substance Abuse Disorders

In a primary care setting the annual health maintenance examination provides an opportunity for identifying adolescents with substance use or abuse issues. The direct questions as well as the assessment of school performance, family relationships, and peer activities may necessitate a more in-depth interview if there are suggestions of difficulties in those areas. Additionally there are several self-report screening questionnaires available with varying degrees of standardization, length, and reliability. The CRAFFT mnemonic is specifically designed to screen for adolescents’ substance use in the primary setting (Table 108-7). Privacy and confidentiality need to be considered when asking the teen about specifics of their substance experimentation or use. Interviewing the parents can provide additional perspective on early warning signs that go unnoticed or disregarded by the teen. Examples of early warning signs of teen substance use are change in mood, appetite, or sleep pattern; decreased interest in school or school performance; loss of weight; secretive behavior about social plans; or valuables such as money or jewelry missing from the home. The use of urine drug screening is recommended when select circumstances are present: (1) psychiatric symptoms to rule out co-morbidity or dual diagnoses, (2) significant changes in school performance or other daily behaviors, (3) frequently occurring accidents, (4) frequently occurring episodes of respiratory problems, (5) evaluation of serious motor vehicular or other injuries, and (6) as a monitoring procedure for a recovery program. Table 108-8 demonstrates the types of tests commonly used for detection by substance, along with the approximate retention time between the use and the identification of the substance in the urine. Most initial screening uses an immunoassay method such as the enzyme-multiplied immunoassay technique followed by a confirmatory test using highly sensitive, highly specific gas chromatography–mass spectrometry. The substances that can cause false-positive results should be considered, especially when there is a discrepancy between the physical findings and the urine drug screen result. In 2007 the American of Academy of Pediatrics released guidelines that strongly discourage home-based or school-based testing.

Table 108-7 CRAFFT MNEMONIC TOOL

Adapted from Anglin TM: Evaluation by interview and questionnaire. In Schydlower M, editor: Substance abuse: a guide for health professionals, ed 2, Elk Grove Village, IL, 2002, American Academy of Pediatrics, p 69.

Diagnosis

Substance abuse is characterized by a maladaptive pattern of use indicated by continued use despite serious consequences or physical harm. Chemical dependence can be defined as a chronic and progressive disease process characterized by loss of control over use, compulsion, and the establishment of an altered state where one requires continued administration of a psychoactive substance in order to feel good or to avoid feeling bad. Diagnosing substance abuse rests on the realization that all children and adolescents are at risk but that some are at substantially more risk than others. Specific diagnostic codes are assigned to substance abuse and substance dependence (Table 108-9). These criteria are used in adults and have limitations in use with adolescents due to differing patterns of use, developmental implications, and other age-related consequences; an additional adolescent-sensitive set of criteria specifically for diagnostic use has not been developed. Adolescents who meet diagnostic criteria should be referred to a program for substance abuse treatment unless the primary care physician has additional training in addiction medicine.

Table 108-9 DSM-IV-TR DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE AND SUBSTANCE DEPENDENCE

SUBSTANCE ABUSE: A maladaptive pattern of substance use leading to clinical significant impairment of distress as manifested by one or more of the following criteria:

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

Prevention

Preventing drug use among children and teens requires prevention efforts aimed at the individual, family, school, and community levels. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) has identified essential principles of successful prevention programs. Programs should enhance protective factors (parent support) and reduce risk factors (poor self-control); should address all forms of drug abuse (legal and illegal); should address the specific type(s) of drug abuse within an identified community; and should be culturally competent to improve effectiveness. See Table 108-10 for examples of risk factors and protective factors within those domains. The highest risk periods for substance use in children and adolescents are during life transitions such as the move from elementary school to middle school, or from middle school to high school. Prevention programs need to target these emotionally and socially intense times for teens in order to adequately anticipate potential substance use or abuse. Examples of effective research-based drug abuse prevention programs featuring a variety of strategies are listed on the NIDA website (www.drugabuse.gov), and on the Center for Substance Abuse Prevention website (www.prevention.samhsa.gov).

Table 108-10 DOMAINS OF RISK AND PROTECTIVE FACTORS FOR SUBSTANCE ABUSE PREVENTION

| RISK FACTORS | DOMAIN | PROTECTIVE FACTORS |

|---|---|---|

| Early aggressive behavior | Individual | Self-control |

| Lack of parental supervision | Family | Parental monitoring |

| Substance abuse | Peer | Academic competence |

| Drug availability | School | Anti–drug use policies |

| Poverty | Community | Strong neighborhood attachment |

From National Institute on Drug Abuse: Preventing drug use among children and adolescents. A research based guide for parents, educators, and community leaders. NIH publication No. 04-4212(B), ed 2, Bethesda, MD, 2003, National Institute on Drug Abuse.

108.1 Alcohol

Alcohol is the most popular drug among teens. By 12th grade, close to 75% of adolescents in U.S. high schools report ever having an alcoholic drink, with 24% having their first drink before age 13 yr; rates are even higher among European youth. Multiple factors can affect a young teen’s risk of developing a drinking problem at an early age (Table 108-11). Moreover, 30% of high school seniors admit to combining drinking behaviors with other risky behaviors such as driving or taking additional substances. Binge drinking remains especially problematic among the older teens and young adults. Thirty-six percent of high school seniors report having 5 or more drinks in a row in the last 30 days. Teens with binge drinking patterns are more likely to be assaulted, engage in high risk sexual behaviors, have academic problems, and acquire injuries than those teens without binge drinking patterns.

Table 108-11 RISK FACTORS FOR A TEEN DEVELOPING A DRINKING PROBLEM

FAMILY RISK FACTORS

INDIVIDUAL RISK FACTORS

Diagnosis

Primary care settings provide opportunity to screen teens for alcohol use or problem behaviors. Brief alcohol screening instruments (CRAFFT [see Table 108-7] or AUDIT [Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test, Table 108-12]) perform well in a clinical setting as techniques to identify Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV)–defined adolescents with alcohol use disorders (Table 108-13). A score of ≥8 on the AUDIT questionnaire identifies people who drink excessively and who would benefit from reducing or ceasing drinking (see Table 108-12). Teenagers in the early phases of alcohol use exhibit few physical findings. Recent use of alcohol may be reflected in elevated gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and amino transferase (AST).

Table 108-12 ALCOHOL USE DISORDERS IDENTIFICATION TEST (AUDIT)

| SCORE (0-4)* | |

|---|---|

| 1. How often do you have a drink containing alcohol? | Never (0) to more than four per week (4) |

| 2. How many drinks containing alcohol do you have on a typical day? | One or two (0) to more than ten (4) |

| 3. How often do you have six or more drinks on one occasion? | Never (0) to daily or almost daily (4) |

| 4. How often during the last year have you found that you were not able to stop drinking once you had started? | Never (0) to daily or almost daily (4) |

| 5. How often during the last year have you failed to do what was normally expected from you because of drinking? | Never (0) to daily or almost daily (4) |

| 6. How often during the last year have you needed a first drink in the morning to get yourself going after a heavy drinking session? | Never (0) to daily or almost daily (4) |

| 7. How often during the last year have you had a feeling of guilt or remorse after drinking? | Never (0) to daily or almost daily (4) |

| 8. How often during the last year have you been unable to remember what happened the night before because you had been drinking? | Never (0) to daily or almost daily (4) |

| 9. Have you or someone else been injured as a result of your drinking? | No (0) to yes, during the last year (4) |

| 10. Has a relative, friend, doctor or other health worker been concerned about your drinking or suggested that you should cut down? | No (0) to yes, during the last year (4) |

* Score ≥8 = problem drinking.

From Schuckit MA: Alcohol-use disorders, Lancet 373:492–500, 2009, Table 1.

Table 108-13 CRITERIA FOR DIAGNOSIS OF ALCOHOL DEPENDENCE, ACCORDING TO DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL (DSM-IV) AND INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF DISEASES (ICD-10)

DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL (DSM-IV)

INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF DISEASES (ICD-10)

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Substance Abuse. Policy statement—alcohol use by youth and adolescents: a pediatric concern. Pediatrics. 2010;125:1078-1087.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Alcohol use among high school students—Georgia, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:885-889.

Howland J, Rohsenow DJ, Arnedt JT, et al. The acute effects of caffeinated versus non-caffeinated alcoholic beverage on driving performance and attention/reaction time. Addiction. 2010;106:335-341.

Kriston L, Hölzel L, Weiser AK, et al. Meta-analysis: are 3 questions enough to detect unhealthy alcohol use? Ann Intern Med. 2008;149:879-888.

McArdle P. Alcohol abuse in adolescents. Arch Dis Child. 2008;93:524-527.

McArdle P. Use and misuse of drugs and alcohol in adolescence. BMJ. 2008;337:46-50.

McCambridge J, McAlaney J, Rowe R. Adult consequences of late adolescent alcohol consumption: a systematic review of cohort studies. PLos Med. 2011;8(2):e100413.

Schuckit MA. Alcohol-use disorders. Lancet. 2009;373:492-500.

Tyler KA. Examining the changing influence of predictors on adolescent alcohol misuse. J Child Adolesc Subst Abuse. 2007;16:95-114.

Walton MA, Chermack ST, Shope JT, et al. Effects of a brief intervention for reducing violence and alcohol misuse among adolescents. JAMA. 2010;304(5):527-535.

108.2 Tobacco

Clinical Manifestations

Adverse health effects from regular smoking include an increased prevalence of chronic cough, sputum production, and wheezing. Smoking during pregnancy is associated with an average decrease in fetal weight of 200 g; this decrease, added to the already smaller size of infants born to teenagers, increases perinatal morbidity and mortality. Tobacco smoke induces hepatic smooth endoplasmic reticulum enzymes and, as a result, may also influence metabolism of drugs such as phenacetin, theophylline, and imipramine. Withdrawal symptoms can occur when adolescents try to quit. Irritability, decreased concentration, increased appetite, and strong cravings for tobacco are common withdrawal symptoms. Nicotine dependence is defined in Table 108-14.

Table 108-14 CHARACTERISTICS OF NICOTINE DEPENDENCE BASED ON THE DIAGNOSTIC AND STATISTICAL MANUAL VERSION IV (DSM-IV) AND THE INTERNATIONAL CLASSIFICATION OF DISEASES REVISION 10 (ICD-10)

DSM-IV CRITERIA

ICD-10 CRITERIA

From American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, fourth edition, text revision, Washington, DC, 2000, American Psychiatric Association.

American Academy of Pediatrics Committees on Environmental Health, Substance Abuse, Adolescence, Native American Child Care. Policy statement–tobacco use: a pediatric disease. Pediatrics. 2009;124:1474-1487.

Becklake MR, Ghezzo H, Ernst P. Childhood predictors of smoking in adolescence: a follow-up study of Montreal schoolchildren. CMAJ. 2005;173:377-379.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2006 national youth tobacco survey and key prevalence indicators. www.cdc.gov/tobacco/data_statistics/surveys/nyts/pdfs/indicators.pdf. Accessed February 20, 2011

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette use among high school students—Unites States, 1991–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:686-688.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Changes in tobacco use among youths aged 13–15 years—Panama, 2002 and 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;57:1416-1419.

Hatsukami D, Stead LF, Gupta PC. Tobacco addiction. Lancet. 2008;371:2027-2038.

Martinasek MP, McDermott RJ, Martini L. Waterpipe (hookah) tobacco smoking among youth. Curr Prob Pediatric Adolesc Med. 2011;41(2):33-58.

Muramoto M, Leischow S, Sherrill D, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 2 dosages of sustained-release bupropion for adolescent smoking cessation. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:1067-1074.

Pollock JD, Koustova E, Hoffman A, et al. Treatments for nicotine addiction should be a top priority. Lancet. 2009;374:513-514.

108.3 Marijuana

Clinical Manifestations

In addition to the “desired” effects of elation and euphoria, marijuana may cause impairment of short-term memory, poor performance of tasks requiring divided attention (e.g., those involved in driving), loss of critical judgment, decreased coordination, and distortion of time perception (Table 108-15). Visual hallucinations and perceived body distortions occur rarely, but there may be “flashbacks” or recall of frightening hallucinations experienced under marijuana’s influence that usually occur during stress or with fever.

Table 108-15 ACUTE AND CHRONIC ADVERSE EFFECTS OF CANNABIS USE

ACUTE ADVERSE EFFECTS

CHRONIC ADVERSE EFFECTS

From Hall W, Degenhardt L: Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use, Lancet 374:1383–1390, 2009.

Smoking marijuana for a minimum of 4 days/wk for 6 mo appears to result in dose-related suppression of plasma testosterone levels and spermatogenesis, prompting concern about the potential deleterious effect of smoking marijuana before completion of pubertal growth and development. There is an antiemetic effect of oral THC or smoked marijuana, often followed by appetite stimulation, which is the basis of the drug’s use in patients receiving cancer chemotherapy. Although the possibility of teratogenicity has been raised because of findings in animals, there is no evidence of such effects in humans. An amotivational syndrome has been described in long-term marijuana users who lose interest in age-appropriate behavior, yet proof of the causative relationship remains equivocal. Chronic use is associated with increased anxiety and depression, learning problems, poor job performance, and respiratory problems such as pharyngitis, sinusitis, bronchitis, and asthma (see Table 108-15).

Aldington S, Williams M, Nowitz M, et al. Effects of cannabis on pulmonary structure, function and symptoms. Thorax. 2007;62:1058-1063.

Bottorff JL, Johnson JL, Moffat BM, et al. Relief oriented use of marijuana by teens. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2009;4:7.

Brook JS, Zhang C, Brook DW. Developmental trajectories of marijuana use from adolescence to adulthood. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(11):55-60.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Inadvertent ingestion of marijuana—Los Angeles, California, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:947-950.

Di Forti M, Morgan C, Dazzan P, et al. High-potency cannabis and the risk of psychosis. Br J Psych. 2009;195:488-491.

Hall W. Is cannabis use psychogenic? Lancet. 2006;367:193-194.

Hall W, Degenhardt L. Adverse health effects of non-medical cannabis use. Lancet. 2009;374:1383-1390.

Nordentoft M, Hjorthøj C. Cannabis use and risk of psychosis in later life. Lancet. 2007;370:293-294.

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. The NSDUH report: marijuana use and perceived risk of use among adolescents 2002 to 2007. Rockville, MD. 2009.

108.4 Inhalants

Inhalants, found in many common household products, comprise a diverse group of volatile substances whose vapors can be inhaled to produce psychoactive effects. The practice of inhalation is popular among younger adolescents and decreases with age. Young adolescents are attracted to these substances because of their rapid action, easy availability, and low cost. Products that are abused as inhalants include volatile solvents (paint thinners, glue), aerosols (spray paint, hair spray), gases (propane tanks, lighter fluid), and nitrites (“poppers” or “video head cleaner”). The most popular inhalants among young adolescents are glue, shoe polish, and spray paint. The various products contain a wide range of chemicals with serious adverse health effects (Table 108-16). Huffing, the practice of inhaling fumes can be accomplished using a paper bag containing a chemical-soaked cloth, spraying aerosols directly into the nose/mouth, or using a balloon, plastic bag, or soda can filled with fumes. The percentage of adolescents using inhalants continues to decline, with 3.9% of high school students reported having used inhalants in the preceding 30-day period (2008); 9% of European youth reported ever using inhalants. Inhalant use has been high among Native American youth perhaps resulting from isolation and lower educational levels; Eskimo youth living in 14 isolated villages in the Bering Strait reported a lifetime of inhalant use of 48%.

Table 108-16 HAZARDS OF CHEMICALS FOUND IN COMMONLY ABUSED INHALANTS

Amyl nitrite, butyl nitrite (“poppers,” “video head cleaner”): sudden sniffing death syndrome, suppressed immunologic function, injury to red blood cells (interfering with oxygen supply to vital tissues)

Benzene (found in gasoline): bone marrow injury, impaired immunologic function, increased risk of leukemia, reproductive system toxicity

Butane, propane (found in lighter fluid, hair and paint sprays): sudden sniffing death syndrome via cardiac effects, serious burn injuries (because of flammability)

Freon (used as a refrigerant and aerosol propellant): sudden sniffing death syndrome, respiratory obstruction and death (from sudden cooling/cold injury to airways), liver damage

Methylene chloride (found in paint thinners and removers, degreasers): reduction of oxygen-carrying of blood, changes to the heart muscle and heartbeat

Nitrous oxide (“laughing gas”), hexane: death from lack of oxygen to the brain, altered perception and motor coordination, loss of sensation, limb spasms, blackouts caused by blood pressure changes, depression of heart muscle functioning

Toluene (found in gasoline, paint thinners and removers, correction fluid): brain damage (loss of brain tissue mass, impaired cognition, gait disturbance, loss of coordination, loss of equilibrium, limb spasms, hearing and vision loss), liver and kidney damage

Trichlorethylene (found in spot removers, degreasers): sudden sniffing death syndrome, cirrhosis of the liver, reproductive complications, hearing and vision damage

Clinical Manifestations

The major effects of inhalants are psychoactive (Table 108-17). The intoxication lasts only a few minutes, so a typical user will huff repeatedly over an extended period of time (hours) in order to maintain the high. The immediate effects of inhalants are similar to alcohol: euphoria, slurred speech, decreased coordination, and dizziness. Toluene, the main ingredient in model airplane glue and some rubber cements, causes relaxation and pleasant hallucinations for up to 2 hr. Euphoria is followed by violent excitement or coma may result from prolonged or rapid inhalation. Volatile nitrites, such as amyl nitrite, butyl nitrite, and related compounds marketed as room deodorizers, are used as euphoriants, enhancers of musical appreciation, and sexual enhancements among older adolescents and young adults. They may result in headaches, syncope, and lightheadedness; profound hypotension and cutaneous flushing followed by vasoconstriction and tachycardia; transiently inverted T waves and depressed ST segments on electrocardiography; methemoglobinemia; increased bronchial irritation; and increased intraocular pressure.

| STAGE | SYMPTOMS |

|---|---|

| 1: Excitatory | Euphoria, excitation, exhilaration, dizziness, hallucinations, sneezing, coughing, excess salivation, intolerance to light, nausea and vomiting, flushed skin and bizarre behavior |

| 2: Early CNS depression | Confusion, disorientation, dullness, loss of self-control, ringing or buzzing in the head, blurred or double vision, cramps, headache, insensitivity to pain, and pallor or paleness |

| 3: Medium CNS depression | Drowsiness, muscular uncoordination, slurred speech, depressed reflexes, and nystagmus or rapid involuntary oscillation of the eyeballs |

| 4: Late CNS depression | Unconsciousness that may be accompanied by bizarre dreams, epileptiform seizures, and EEG changes |

CNS, central nervous system; EEG, electroencephalogram.

From Harris D: Volatile substance abuse, Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 91:ep93-ep100, 2006, Table 1.

Complications

Model airplane glue is responsible for a wide range of complications, related to chemical toxicity, to the method of administration (in plastic bags, with resultant suffocation), and to the often dangerous setting in which the inhalation occurs (inner-city roof tops). Common neuromuscular changes reported in chronic inhalant abusers include difficulty coordinating movement, gait disorders, muscle tremors, and spasticity, particularly in the legs (Table 108-18). Moreover, chronic use may cause pulmonary hypertension, restrictive lung defects or reduced diffusion capacity, peripheral neuropathy, hematuria, tubular acidosis, and possibly cerebral and cerebellar atrophy. Chronic inhalant abuse has long been linked to widespread brain damage and cognitive abnormalities that can range from mild impairment (poor memory, decreased learning ability) to severe dementia. Death in the acute phase may result from cerebral or pulmonary edema or myocardial involvement (see Table 108-18).

Table 108-18 DOCUMENTED CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS OF VOLATILE SUBSTANCE ABUSE (VSA)

| CLINICAL PRESENTATIONS OF ACUTE AND CHRONIC VSA | |

| Ventricular fibrillation | Muscle weakness |

| Asystolic cardiac arrest | Abdominal pain |

| Myocardial infarction | Cough |

| Ataxia | Aspiration pneumonia |

| Agitation | Chemical pneumonitis |

| Limb and trunk uncoordination | Coma |

| Tremor | Visual and auditory hallucinations |

| Visual loss | Acute delusions |

| Tinnitus | Nausea and vomiting |

| Dysarthria | Pulmonary edema |

| Vertigo | Photophobia |

| Hyperreflexia | Rash |

| Acute confusional state | Jaundice |

| Conjunctivitis | Anorexia |

| Acute paranoia | Slurred speech |

| Depression | Diarrhea |

| Oral and nasal mucosal ulceration | Weight loss |

| Halitosis | Epistaxis |

| Convulsions/fits | Rhinitis |

| Headache | Cerebral edema |

| Peripheral neuropathy | Visual loss |

| Methemoglobinemia | Burns |

| Acute trauma | Renal tubular acidosis |

From Harris D: Volatile substance abuse, Arch Dis Child Edu Pract Ed 91:ep93-ep100, 2006, Table 2.

Harris D. Volatile substance abuse. Arch Dis Child Edu Pract Ed. 2006;91:ep93-ep100.

Marsolek MR, White NC, Litovitz TL. Inhalent abuse: monitoring trends by using poison control data, 1993–2008. Pediatrics. 2010;125:906-913.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA infofacts: inhalants. website www.nida.nih.gov/infofacts/inhalants.html Accessed April 21, 2010

National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Adolescent inhalant use and selected respiratory conditions. http://www.oas.samhsa.gov/2k10/175/175RespiratoryCondHTML.pdf. Accessed March 23, 2011

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Applied Studies. The NSDUH report: trends in adolescent inhalant use: 2002 to 2007. Rockville, MD. 2009.

Williams JF, Storck M, Committee on Substance Abuse and Committee on Native American Child Health Inhalant Abuse. Inhalant abuse. Pediatrics. 2007;119:1009-1017.

108.5 Hallucinogens

Methylenedioxymethamphetamine

MDMA (“X,” Ecstasy), a phenylisopropylamine hallucinogen, is a synthetic compound similar to hallucinogenic mescaline and the stimulant methamphetamine. Like other hallucinogens, this drug is proposed to interact with serotoninergic neurons in the central nervous system (CNS). It is the preferred drug at “raves,” all-night dance parties, and is also known as one of the “club drugs” along with γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) and ketamine (see Table 108-5). Between 2005 and 2008, past-year use of MDMA increased among both 10th and 12th graders. Six percent of 12th graders report having tried MDMA at least once. Similar increases were seen among European youth; the European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs reported that in 2007, 3% of European students report having tried ecstasy during their lifetime, with 5 countries reporting ever-use rates of 6-7%.

Bryner JK, Wang UK, Hui JW, et al. Dextromethorphan abuse in adolescence. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:1217-1222.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Ecstasy overdoses at a New Year’s eve rave—Los Angeles, CA, 2010. MMWR. 2010;59(22):677-680.

Halpern JH, Sherwood AR, Hudson JI, et al. Residual neurocognitive features of long-term ecstasy users with minimal exposure to other drugs. Addiction. 2010;106:777-786.

Hysek CM, Vollenweider FX, Liechti ME. Effects of a β-blocker on the cardiovascular response to MDMA (Ecstacy). Emerg Med J. 2010;27:586-589.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA infofacts: club drugs (GHB, ketamine, and rohypnol). (website) www.nida.nih.gov/infofacts/Clubdrugs.html Accessed April 21, 2010

Poikolainen K. Ecstasy and the antecedents of illicit drug use. BMJ. 2006;332:803-804.

Ricaurte GA, McCann UD. Recognition and management of complications of new recreational drug use. Lancet. 2005;365:2137-2145.

Snead OCIII, Gibson KM. γ-Hydroxybutyric acid. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2721-2732.

108.6 Cocaine

Cocaine, an alkaloid extracted from the leaves of the South American Erythroxylon coca, is supplied as the hydrochloride salt in crystalline form. With “snorting” it is rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream from the nasal mucosa, detoxified by the liver, and excreted in the urine as benzoylecgonine. Smoking the cocaine alkaloid (“freebasing”) involves inhaling the cocaine vapors in pipes, or cigarettes mixed with tobacco or marijuana. Accidental burns are potential complications of this practice. With crack cocaine, the crystallized rock form, the smoker feels “high” in <10 sec. The risk of addiction with this method is higher and more rapidly progressive than from snorting cocaine. Tolerance develops and the user must increase the dose or change the route of administration, or both, to achieve the same effect. In order to sustain the high, cocaine users repeatedly use cocaine in short periods of time known as “binges.” Drug dealers often place cocaine in plastic bags or condoms and swallow these containers during transport. Rupture of a container produces a sympathomimetic crisis (see Table 108-6). Cocaine use among high school students has remained unchanged in the last decade, with 7.2% of 12th graders having tried the drug (any route) at least once. Average use rates are somewhat lower among European students.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Syringe exchange programs—United States, 2008. MMWR. 2010;59(45):1488-1492.

Kerr T, Montaner JSG, Wood E. Sciences and politics of heroin prescription. Lancet. 2010;375:1849-1850.

Marsden J, Eastwood B, Bradbury C, et al. Effectiveness of community treatments for heroin and crack cocaine addiction in England: a prospective, in-treatment cohort study. Lancet. 2009;374:1262-1270.

Starrels JL, Becker WC, Alford DP, et al. Systematic review: treatment agreements and urine drug testing to reduce opioid misuse in patients with chronic pain. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:712-720.

108.7 Amphetamines

Clinical Manifestations

Methamphetamine rapidly increases the release and blocks the reuptake of dopamine, a powerful “feel good” neurotransmitter (Table 108-19). The effects of amphetamines can be dose related. In small amounts amphetamine effects resemble other stimulants: increased physical activity, rapid and/or irregular heart rate, increased blood pressure and decreased appetite. High doses produce slowing of cardiac conduction in the face of ventricular irritability. Hypertensive and hyperpyrexic episodes can occur as seizures (see Table 108-6). Binge effects result in the development of psychotic ideation with the potential for sudden violence. Cerebrovascular damage, psychosis, severe receding of the gums with tooth decay, and infection with HIV and hepatitis B and C can result from long-term use. There is a withdrawal syndrome associated with amphetamine use, with early, intermediate, and late phases. The early phase is characterized as a “crash” phase with depression, agitation, fatigue, and desire for more of the drug. Loss of physical and mental energy, limited interest in the environment, and anhedonia mark the intermediate phase. In the final phase, drug craving returns, often triggered by particular situations or objects.

Setlik J, Bond R, Ho M. Adolescent prescription ADHA medication abuse is rising along with prescriptions for these medications. Pediatrics. 2009;124:875-880.

Spoth RL, Clair S, Shin C, et al. Long-term effects of universal preventive interventions on methamphetamine use among adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:876-882.

108.8 Opiates

Clinical Manifestations

The clinical manifestations are determined by the purity of the heroin or its adulterants, combined with the route of administration. The immediate effects include euphoria, diminution in pain, flushing of the skin, and pinpoint pupils (Table 108-19). An effect on the hypothalamus is suggested by the lowering of body temperature. The most common dermatologic lesions are the “tracks,” the hypertrophic linear scars that follow the course of large veins. Smaller, discrete peripheral scars, resembling healed insect bites, may be easily overlooked. The adolescent who injects heroin subcutaneously may have fat necrosis, lipodystrophy, and atrophy over portions of the extremities. Attempts to conceal these stigmata may include amateur tattoos in unusual sites. Skin abscesses secondary to unsterile techniques of drug administration are commonly found. There is a loss of libido; the mechanism is unknown. The chronic heroin user may resort to prostitution to support the habit, thus increasing the risk of sexually transmitted diseases (including HIV), pregnancy, and other infectious diseases. Constipation results from decreased smooth muscle propulsive contractions and increased anal sphincter tone. The absence of sterile technique in injection may lead to cerebral microabscesses or endocarditis, usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Abnormal serologic reactions are also common, including false-positive Venereal Disease Research Laboratory and latex fixation tests.

Withdrawal

After a period of ≥8 hr without heroin, the addicted individual undergoes, during a 24-36 hr period, a series of physiologic disturbances referred to collectively as “withdrawal” or the abstinence syndrome (see Table 108-19). The earliest sign is yawning, followed by lacrimation, mydriasis, restlessness, insomnia, “goose flesh,” cramping of the voluntary musculature, bone pain, hyperactive bowel sounds and diarrhea, tachycardia, and systolic hypertension. While the administration of methadone has been the most common method of detoxification, the addition of buprenorphine, an opiate agonist-antagonist, is available for detoxification and maintenance treatment of heroin and other opiates. This medication has the advantage in that it offers less risk of addiction and overdose, and withdrawal effects and can be dispensed in the privacy of a physician’s office. Combined with behavioral interventions, it has a greater success rate of detoxification. A combination drug, buprenorphine/naloxone has been formulated to minimize abuse during detoxification.

Baca CT, Grant KJ. Take-home naloxone to reduce heroin death. Addiction. 2005;100:1823-1831.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Overdose deaths involving prescription opioids among Medicaid enrollees—Washington, 2004–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:1171-1174.

Doe-Simkins M, Walley AY, Epstein A, et al. Saved by the nose: bystander-administered intranasal naloxone hydrochloride for opioid overdose. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:788-791.

Fiellin DA. Treatment of adolescent opioid dependence. JAMA. 2008;300:2057-2058.

McCabe SE, Boyd CJ, Cranford JA, et al. Motives for nonmedical use of prescription opioids among high school seniors in the United States. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2009;163:739-744.

Oviedo-Joekes E, Brissette S, Marsh DC, et al. Diacetylmorphine versus methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction. N Engl J Med. 361, 2009. 777–768

Woody GE, Poole SA, Subramaniam G, et al. Extended vs short-term buprenorphine-naloxone for treatment of opioid-addicted youth. JAMA. 2009;300:2003-2011.

2002 Acute reactions to drugs of abuse. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2002;44:21-24.

Bonomo Y, Proimos J. Substance misuse: alcohol, tobacco, inhalants, and other drugs. Br Med J. 2005;330:777-780.

Chandler RK, Fletcher BW, Volkow ND. Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system. JAMA. 2009;301:183-190.

Eaton D, Kann L, Shanklin S, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance–United States, 2007. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2008;57(4):1-131.

Friedman RA. The changing face of teenage drug abuse—the trend toward prescription drugs. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1448-1450.

Haber PS, Demirkol A, Lange K, et al. Management of injecting drug users admitted to hospital. Lancet. 2009;374:1284-1292.

Hibell B, Guttormsson U, Ahlström S, et al. The 2007 ESPAD Report. Substance use among students in 35 European countries. The Swedish Council for Information on Alcohol and Other Drugs (CAN). Stockholm. 2009.

Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009;16:12-20.

Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, et al. Monitoring the future: national results on adolescent drug use: overview of key findings, 2008 (NIH Publication No. 09–7401). Bethesda, MD: National Institute on Drug Abuse; 2008.

Levy S, Sherritt L, Vaughn BL, et al. Results of random drug testing in an adolescent substance abuse program. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e843-e848.

Nutt D, King LA, Saulsbury W, et al. Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse. Lancet. 2007;369:1047-1053.

Toumbourou JW, Stockwell T, Neighbors C, et al. Interventions to reduce harm associated with adolescent substance use. Lancet. 2007;369:1391-1401.