69 Stiff Person Syndrome

This chapter concentrates on the most common of the very uncommon motor neuron hyperactivity disorders, namely the stiff person syndrome. Two other potentially related syndromes characterized by incomplete relaxation or inhibition of motor neurons—Isaac (Merten) syndrome and neuromyotonia—are discussed in Chapter 70.

Etiology

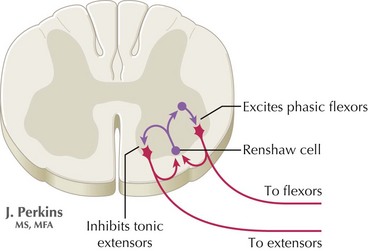

The precise pathophysiologic role for the specific antibodies is unclear, although it is speculated that the autoimmune lesions are directed at a site on the inhibitory spinal interneurons (Fig. 69-1). Although a direct relation is inferred, this is not fully substantiated. Factors supporting a direct role for antibodies are (1) the finding of elevated intrathecal GAD antibodies; (2) the antibody concentration correlates with the degree of motor excitability; (3) GAD antibodies, obtained from serum of stiff person patients, inhibit both GAD and GABA synthesis in vitro.

Clinical Presentation

Classic SPS

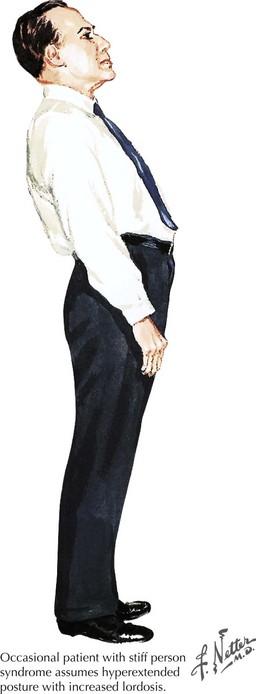

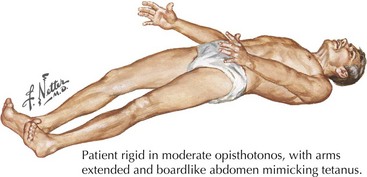

Typically this is characterized by spine and leg rigidity with lumbar hyperlordosis as a key feature (Figs. 69-2 and 69-3). Lower extremity rigidity can cause full extension of the legs, making walking difficult. Patients often also experience superimposed painful spasms that may be precipitated by sudden noise, anxiety, or touch. The spasms can be of such abrupt onset and power that these individuals may unexpectedly and precipitously fall. Patients soon recognize that emotional stress often provokes their spasms. They may develop agoraphobia secondary to the fear of falling in public. Neurologic examination sometimes reveals paraspinal and abdominal musculature contraction with lumbar hyperlordosis and lower limb rigidity. However, these findings are often not present until late in the clinical course. The muscle stretch reflexes may be normal to brisk, with occasionally extensor plantar responses.

Diagnostic Approach

Stiff person syndrome is primarily a clinical diagnosis, and diagnostic criteria include:

Treatment and Prognosis

Amato AA, Cornman EW, Kissel JT. Treatment of stiff-man syndrome with intravenous immunoglobulin. Neurology. 2004;44:1652-1654.

Barker RA, Revesz T, Thom M, et al. Review of 23 patients affected by the stiff person syndrome: clinical subdivision into stiff trunk (man) syndrome, stiff limb syndrome, and progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1998;65:633-640.

Burns TM, Jones HRJr, Phillips LHII, et al. Two generations of clinically disparate stiff man syndrome, confirmed by significant elevations of GAD65 autoantibodies. Neurology. 2003;61:1291-1294.

Dalakas MC, Li M, Fujii M, et al. Stiff person syndrome: quantification, specificity, and intrathecal synthesis of GAD 65 antibodies. Neurology. 2001;57:780-784.

Lockman J, Burns TM. Stiff-person syndrome. Current Treatment Options Neurol. 2007;9:234-240.

Moersch FP, Woltman HW. Progressive fluctuating muscular rigidity and spasm (“stiff-man” syndrome): report of a case and some observations in 13 other cases. Mayo Clin Proc. 1956;31:421-427. The initial and very classic paper with exquisitely detailed patient history