Chapter 222 Spondylotic Myelopathy with Cervical Kyphotic Deformity

Ventral Approach

The development of cervical spine deformity may be secondary to advanced degenerative disease, trauma, neoplastic disease, or surgery.1 It may also occur in patients with systemic arthritides, such as ankylosing spondylitis and rheumatoid arthritis.

The most common cause of cervical kyphosis is iatrogenic (postsurgical).2 This most commonly occurs after laminectomy. The surgical procedure involves disruption of the dorsal tension-band. The incidence of clinically significant kyphosis in this situation may be as high as 21%.3 Kyphosis may also occur following ventral cervical surgery. This may be due to pseudarthrosis or failure to restore the anatomic cervical lordosis during surgery.4,5

Whatever the cause, the development of cervical deformity should be avoided and corrected when appropriate. Axial loading tends to further the kyphosis, thus creating a vicious cycle and progression of the deformity.6 The deformity tends to cause neck pain, which is mechanical in nature.7 The pain is due to a biomechanical disadvantage placed on the cervical musculature and degeneration of the adjacent cervical discs. In advanced cases, forward gaze, swallowing, and respiration may be adversely affected.

Ventral versus Dorsal Approach

Sagittal plane deformity in the cervical spine may be corrected ventrally,8–11 dorsally,12,13 or ventrally and dorsally (in combination).12,14–16 The ventral approach is one that is familiar to most spine surgeons and may be performed with minimal morbidity.

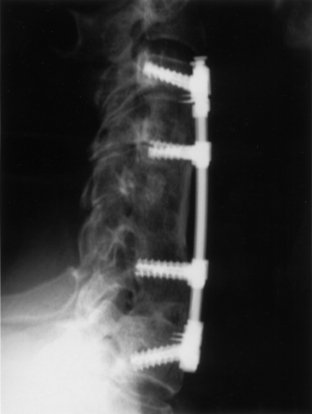

Many patients with cervical kyphosis have had a prior cervical operation, often a laminectomy (Fig. 222-1). A dorsal revision strategy is associated with increased morbidity with regard to wound complications, pain, and the risk of neurologic injury. A ventral approach is advantageous in that “virgin” surgical territory is entered. If a prior ventral approach had been performed, the same approach may be used without difficulty, or the opposite side of the neck may be entered for the revision. These factors decrease the morbidity associated with revision cervical surgery.

Using a dorsal-alone strategy, one is most often unable to correct cervical kyphosis significantly. Only if the deformity is “flexible” and is able to be corrected with cervical traction may a dorsal alone strategy be used. This finding is not at all common. More often, a ventral release procedure is required prior to the dorsal deformity correction procedure. A dorsal deformity correction procedure, with or without a ventral release, may not fully correct the deformity. Even with the use of cervical pedicle screws, Abumi et al. were able to correct cervical deformity only from 28.4 to 5.1 degrees of kyphosis, with all patients achieving a solid arthrodesis.12 A ventral strategy provides a better surgical leverage for deformity correction while providing very solid fixation points if intermediate points of fixation are used.6

As mentioned previously, using multiple points of intermediate fixation is optimal with ventral deformity correction strategies. This is accomplished by leaving intermediate vertebral bodies in place, instead of performing multiple adjacent corpectomies. These intermediate bodies provide solid fixation points for intermediate points of screw fixation. These intermediate points facilitate the “bringing of the spine” to a contoured implant to achieve further lordotic correction. They also provide three- or four-point bending forces to prevent deformity progression and construct failure.6 These intermediate fixation points may also be provided with dorsal lateral mass fixation, but entail the addition of a dorsal procedure, in addition to a ventral decompression procedure.

Axially dynamic cervical implants further add to the success of a ventral deformity correction procedure.17 These constructs are able to provide for the placement of multiple intermediate points of fixation. The dynamic aspect of the implant is able to off-load stresses at the screw/implant interface, which aids in the prevention of nonunion and construct failure, and also provides solid fixation for the prevention of cervical deformity progression.

Clinical Experience

We use a ventral-only approach for the correction of cervical kyphosis in specific clinical scenarios. This technique is optimally used when the kyphosis is fixed (i.e., rigid) and the facet joints are not ankylosed. If the facet joints or other dorsal elements are fused, a dorsal osteotomy is required. Ankylosis may easily be determined by fine-cut CT scanning. The clinical technique has been previously described,17,18 and surgical steps will be briefly outlined here.

We have reported our experience with this technique with 12 patients. A dynamic implant was us in most patients.17 The majority of patients presented with mechanical neck pain as part of their symptom complex. The average magnitude of deformity correction (preoperative to postoperative) was 20 degrees of lordosis. The average postoperative sagittal angle was 6 degrees of lordosis. The average change in the sagittal angle during the follow-up period was 2.2 degrees of lordosis.

Using this ventral technique, lordosis was attained in all but one patient (Fig. 222-2). This posture was effectively maintained during the follow-up period. All patients demonstrated improvement postoperatively, and three had complete resolution of their preoperative symptoms.

Albert T.J., Vacarro A. Postlaminectomy kyphosis. Spine. 1998;23:2738-2745.

Buttler J.C., Whitecloud T.S.III. Postlaminectomy kyphosis: causes and surgical management. Clin Orthop North Am. 1992;23:505-511.

Herman J.M., Sonntag V.K. Cervical corpectomy and plate fixation for post-laminectomy kyphosis. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:963-970.

Kaptain G.J., Simmons N., Replogle R.E., Pobereskin L. Incidence and outcome of kyphotic deformity following laminectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(Suppl 2):199-204.

Steinmetz M.P., Kager C., Benzel E.C. Anterior correction of postsurgical cervical kyphosis. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(Suppl 2):1-7.

Zdeblick T.A., Bohlman H.H. Cervical kyphosis and myelopathy: treatment by anterior corpectomy and strut-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1989;71:170-182.

1. Johnston F.G., Crockard H.A. One stage internal fixation an anterior fusion in complex cervical spinal disorders. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:234-238.

2. Albert T.J., Vacarro A. Postlaminectomy kyphosis. Spine. 1998;23:2738-2745.

3. Kaptain G.J., Simmons N., Replogle R.E., Pobereskin L. Incidence and outcome of kyphotic deformity following laminectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(Suppl 2):199-204.

4. Caspar W., Pitzen T. Anterior cervical fusion and trapezoidal plate stabilization for re-do surgery. Surg Neurol. 1999;52:345-352.

5. Geisler F.H., Caspar W., Pitzen T., et al. Reoperation in patients after anterior cervical plate stabilization in degenerative disease. Spine. 1998;23:911-920.

6. Benzel E.C. Biomechanics of spine stabilization. Rolling Meadows, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 2001.

7. Katsuura A., Hukuda S., Imanaka T., et al. Anterior cervical plate used in degenerative disease can maintain cervical lordosis. J Spine Disord. 1996;9:470-476.

8. Buttler J.C., Whitecloud T.S.III. Postlaminectomy kyphosis: causes and surgical management. Clin Orthop North Am. 1992;23:505-511.

9. Cattrell H.S., Clark G.J.Jr. Cervical kyphosis and instability following multiple laminectomies in children. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1967;49:713-720.

10. Herman J.M., Sonntag V.K. Cervical corpectomy and plate fixation for post-laminectomy kyphosis. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:963-970.

11. Zdeblick T.A., Bohlman H.H. Cervical kyphosis and myelopathy: treatment by anterior corpectomy and strut-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1989;71:170-182.

12. Abumi K., Shono Y., Taneichi H. Correction of cervical kyphosis using pedicle screw fixation systems. Spine. 1999;24:2389-2396.

13. Callahan R.A., Johnson R.M., Margolis R.N. Cervical facet fusion for control of instability following laminectomy. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1977;59:991-1002.

14. Heller J.G., Silcox D.H.III, Sutterlin C.E.III. Complications of posterior cervical plating. Spine. 1995;20:2442-2448.

15. McAfee P.C., Bohlman H.H., Ducker T.B. One stage anterior cervical decompression and posterior stabilization. A study of one hundred patients with a minimum of two years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1995;77:1791-1800.

16. Savini R., Parisini P., Cervellati S. The surgical treatment of late instability of flexion-rotation injuries in the lower cervical spine. Spine. 1987;12:178-182.

17. Steinmetz M.P., Kager C., Benzel E.C. Anterior correction of postsurgical cervical kyphosis. J Neurosurg. 2003;98(Suppl 2):1-7.

18. Steinmetz M.P., Stewart T.J., Kager C., et al. Cervical deformity correction. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(Suppl 1):S90-S97.

Dorsal Approach

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) is a chronic spinal degenerative condition characterized by progressive symptoms of neck pain, upper extremity numbness and motor weakness, spastic gait disturbance, urinary dysfunction, hyperreflexia, and impotence. The primary pathophysiologic mechanism is a progressive narrowing of the sagittal diameter of the spinal canal due to a host of mechanical factors.1 White and Panjabi have subdivided the mechanical factors into two groups: static factors (congenital spinal canal stenosis, disc herniation, osteophytosis, and ligament hypertrophy) and dynamic factors (abnormal forces placed on the spinal cord during normal range of motion of the cervical spine).2 As the degenerative spinal elements compress the spinal cord, blood vessels can simultaneously be compressed, causing chronic cord ischemia and myelomalacia.3 Several studies have demonstrated that early surgical intervention can improve prognosis and prevent continued neurologic decline, as well as decrease the risk of sudden spinal cord injury from minor events.4–7

There has been much debate as to the most optimal surgical approach for a patient with CSM, and once the recommendation has been made for surgery, often the approach is tailored to the individual patient. Assessment of the sagittal alignment of the patient’s cervical spine is of utmost importance when considering the best surgical approach, because CSM is often associated with loss of cervical lordosis (so-called “spine straightening”) or cervical kyphotic deformity. In the case of cervical kyphotic deformity, the spinal cord shifts ventrally in the canal and abuts the ventral spinal elements at the apex of the deformity. As the deformity progresses, the static and dynamic mechanical stresses applied to the spinal cord increase, leading to worsening neurologic function.8 To most effectively manage patients with this pathologic variation, surgical intervention must be targeted at adequate decompression of the neural elements and prevention of progression, if not outright correction, of the cervical kyphosis.

There are three major options for surgical management of CSM: the ventral approach, dorsal approach, or a combination of the two. Several studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of the ventral approach in treating CSM.9,10 The ventral approach is heavily favored by many surgeons who treat CSM, especially in the presence of a cervical kyphotic deformity.11 The ventral approach can be used to treat pathology limited to one or two levels (via ventral cervical discectomy and fusion) and over three or more levels (via subtotal cervical corpectomy and strut graft, usually in conjunction with dorsal instrumentation). Unfortunately, long-segment ventral procedures have been associated with a high rate of pseudarthrosis, graft dislodgement and subsidence, or construct failure.9,12 Several options are available if the surgeon chooses to use solely a dorsal approach. However, because the source of the pathology in CSM with kyphotic deformity is ventral to the spinal cord, the chosen dorsal approach must not only effectively decompress the neural elements, but also correct the kyphotic deformity to allow the spinal cord to migrate dorsally away from the ventral compressive elements. In this chapter, the focus is placed on the major dorsal approaches available to treat CSM and the pros and cons of each.

Cervical Laminectomy and Lateral Mass Fusion

Cervical laminectomy for the treatment of CSM has been shown to be safe and effective. As a stand-alone treatment for CSM, cervical laminectomy has recently fallen out of favor with many surgeons because of the risk of development of postlaminecomy kyphosis. Ryken et al.13 performed a systematic review of the National Library of Medicine and the Cochrane database to examine the efficacy of cervical laminectomy for the treatment of CSM and concluded that it remains a viable consideration for treatment of CSM. They found that the risk of developing postlaminectomy kyphosis in patients undergoing laminectomy for CSM ranges from 14% to 47%. It is unclear how this risk relates to clinical outcome; however, a straight or kyphotic cervical spine alignment is associated with an augmented risk of developing a postlaminectomy kyphosis.

In an attempt to avoid the development of late kyphosis after laminectomy, many surgeons opt to perform a lateral mass fusion at the time of laminectomy. Gok et al.14 retrospectively reviewed 54 patients who underwent cervical laminectomy and fusion for CSM. Patients were selected if they had clinical signs of myelopathy and cervical lordosis or straight spine with advanced age (>65 years) and significant medical comorbidities. In this study, 81% of patients improved in Nurick grade, and the remaining 19% remained the same. Ten percent required revision surgery, and only 4% (2 patients) had lateral mass screw pull-out. Anderson et al.15 performed a systematic review of the Cochrane database and the National Libary of Medicine to examine the efficacy of cervical laminectomy and fusion for CSM. Although the evidence is largely class III, the investigators concluded that 70% to 95% of patients show neurologic improvement with this procedure, and overall recovery is approximately 50% of the initial Japanese Orthopaedic Association (JOA) score deficit. Several other studies16–18 reported good success with cervical laminectomy and fusion. However, patients with preexisting cervical kyphosis were universally excluded from all of these studies.

Although cervical laminectomy with or without lateral mass fusion may be successful in the treatment of CSM in patients with lordotic or slightly straight cervical alignment, these procedures are contraindicated in patients with a kyphotic spine. Because the spinal cord is draped over a kyphotic deformity, it does not shift dorsally after laminectomy. This often results in suboptimal surgical results and progression of neurologic decline. Furthermore, a laminectomy in the presence of kyphosis may worsen the deformity.13,14,17 Therefore, kyphosis in the setting of CSM is considered to be a contraindication to laminectomy with or without lateral mass fusion.

Cervical Laminoplasty

Cervical laminoplasty is effective for the treatment of CSM. “Open-door” or “canal expansive” cervical laminoplasty was originally developed in Japan for the treatment of multilevel CSM, especially for treatment of ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL).19 Laminoplasty was initially used as a strategy to avoid the common complication of postlaminectomy kyphosis, the rationale being that the laminae that are left behind will form points of attachment for the cervical musculature during healing, thus retaining the dorsal tension-band and preventing the development of postsurgical kyphotic deformity. The technique relies on two mechanisms for success. The first is a direct dorsal decompressive effect from removal of the laminae and expansion of the cervical spinal canal. The second is an indirect decompressive effect from migration of the cervical spinal cord dorsally away from the ventral compressive structures.20 There are several variations of the laminoplasty (French door, Z-plasty, to name a few).

This technique proves most effective in patients with CSM and intact cervical lordosis or mild spinal straightening, because the cervical cord is able to shift dorsally after laminoplasty in these patients. Several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of this procedure in preventing postsurgical kyphosis and improving neurologic status in properly selected patients.21–24 However, the presence of cervical kyphosis in conjunction with CSM is widely considered an absolute contraindication to laminoplasty. Nearly all of the major prospective studies examining the efficacy of laminoplasty in the management of CSM excluded patients with presurgical kyphotic deformity. The vast majority of patients with CSM and a kyphotic deformity who undergo laminoplasty develop worsening of their kyphosis and further neurologic deterioration, necessitating a second corrective surgery. Kimura et al.25 examined 29 patients treated with laminoplasty for CSM and found that patients with preexisting kyphotic or S-shaped swan-neck deformity did significantly worse than those with preexisting lordotic alignment. Suda et al.20 determined that the maximum preoperative local kyphosis angle for successful expansive laminoplasty is less than 13 degrees (approximately).

Cervical Pedicle-Screw Fixation

The major shortcoming of most dorsal cervical spine procedures in the setting of CSM with kyphosis is the failure to allow the spinal cord to shift dorsally after the procedure, which occurs because most dorsal procedures do not restore lordosis to the spine, and most actually worsen preexisting kyphosis or reduce lordosis. For a dorsal procedure to adequately treat CSM with kyphosis, the procedure must not only decompress the spinal cord but also correct the kyphotic deformity and restore lordosis. Furthermore, such a procedure must provide enough structural integrity to withstand the considerable biomechanical forces in play as the surgeon attempts to reduce cervical kyphosis. Dorsal cervical decompression and pedicle-screw instrumentation is a technique that has been used with success in this situation. It provides a biomechanical advantage over lateral mass screw fixation, in that several biomechanical and clinical studies demonstrate the increased stability of pedicle-screw fixation over lateral mass fixation.26,27 Although it provides superior biomechanical strength and greater potential for kyphosis reduction, when compared with lateral mass instrumentation, cervical pedicle-screw fixation is also associated with a higher complication rate and is a much more technically difficult procedure.

Cervical pedicle screws provide greater stability and increased pull-out strength when compared with lateral mass screws.28,29 Hasegawa et al.30 reviewed their series of 58 patients with and without destructive lesions of the cervical spine treated with dorsal decompression and pedicle-screw fixation. They found that postoperative kyphosis was reduced and maintained when compared with laminoplasty alone for management of CSM with kyphotic deformity. However, there was no difference in JOA score improvement between the two groups, and 17.2% of patients experienced serious complications from pedicle-screw placement (including two vertebral artery injuries). Hasegawa concluded that pedicle-screw fixation has a definite application to cervical diseases with kyphosis and loss of stability but no role in the management of “typical” CSM and OPLL (i.e., without kyphosis) or in postlaminectomy kyphosis (for which they recommend ventral decompression and/or a safer dorsal instrumentation).

Abumi et al.31 reported their results in 30 patients with cervical kyphosis with a variety of etiologies (trauma, degenerative, rheumatoid, infectious, and postlaminectomy) treated with cervical pedicle-screw fixation. Of the 30 patients, 17 were managed with a dorsal procedure alone, and 13 were managed with a combined ventral and dorsal approach. In the case of rigid kyphosis, a ventral procedure was necessary to provide release for dorsal kyphosis reduction. In both groups, kyphosis improved from an average of 28.4 degrees to 4.4 degrees postoperatively and 5.1 degrees at an average of 42 months follow-up. The combined approach resulted in outright reversal of kyphosis to 0.3 degrees of lordosis postoperatively and 0.5 degrees of kyphosis at an average of 42 months follow-up. Of the 24 patients who had CSM preoperatively, 14 saw an improvement in Frankel grade and 10 remained at the same grade. No patients deteriorated neurologically, although 6.3% of the screws placed were in malposition and two patients required screw revision. Abumi has demonstrated that in patients with kyphosis associated with some degree of segmental motion, pedicle-screw fixation is a reliable and stable construct for kyphosis reduction and stabilization in conjunction with a dorsal decompressive procedure. Abumi also has concluded that cervical kyphosis in the setting of CSM with bony union mandates a combined dorsal-ventral approach.

A major drawback of the cervical pedicle-screw fixation technique is its technical difficulty and associated potentially disastrous complication rate. It is recommended that this procedure should be attempted by surgeons who have a great deal of experience with this technique and only in patients with proper indications. In another study, Abumi et al.32 reported a series of 180 patients who underwent cervical pedicle-screw fixation. A total of 712 screws were placed in these patients, and 669 of these were radiographically evaluated postoperatively. One patient suffered a vertebral artery injury but no neurologic complication from this. Forty-five (6.7%) of the screws placed were found to violate the pedicle; two of these screws caused radiculopathy, and nine of these perforated laterally into the foramen transversarium.

Abumi K., Shono Y., Ito M., et al. Complications of pedicle screw fixation in reconstructive surgery of the cervical spine. Spine. 2000;25:962-969.

Abumi K., Shono Y., Taneichi H., et al. Correction of cervical kyphosis using pedicle screw fixation systems. Spine. 1999;24:2389-2396.

Suda K., Abumi K., Ito M., et al. Local kyphosis reduces surgical outcomes of expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. 2003;28:1258-1262.

Uchida K., Nakajima H., Sato R., et al. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy associated with kyphosis or sagittal sigmoid alignment: outcome after anterior or posterior decompression. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11:521-528.

White A.A.III, Panjabi M.M. Biomechanical considerations in the surgical management of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. 1988;13:856-860.

1. Jankowitz B.T., Gerszten P.C. Decompression for cervical myelopathy. Spine J. 2006;6:S317-S322.

2. White A.A.III, Panjabi M.M. Biomechanical considerations in the surgical management of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. 1988;13:856-860.

3. McCormick W.E., Steinmetz M.P., Benzel E.C. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: make the difficult diagnosis, then refer for surgery. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70:899-904.

4. Clarke E., Robinson P.K. Cervical myelopathy: a complication of cervical spondylosis. Brain. 1956;79:483-510.

5. Montgomery D.M., Brower R.S. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Clinical syndrome and natural history. Orthop Clin North Am. 1992;23:487-493.

6. Ebersold M.J., Pare M.C., Quast L.M. Surgical treatment for cervical spondylitic myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:745-751.

7. Phillips D.G. Surgical treatment of myelopathy with cervical spondylosis. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1973;36:879-884.

8. Uchida K., Nakajima H., Sato R., et al. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy associated with kyphosis or sagittal sigmoid alignment: outcome after anterior or posterior decompression. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11:521-528.

9. Koller H., Hempfing A., Ferraris L., et al. 4- and 5-level anterior fusions of the cervical spine: review of literature and clinical results. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:2055-2071.

10. Chagas H., Domingues F., Aversa A., et al. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: 10 years of prospective outcome analysis of anterior decompression and fusion. Surg Neurol. 2005;64(Suppl 1):30-35. discussion 35–36

11. Medow J.E., Trost G., Sandin J. Surgical management of cervical myelopathy: indications and techniques for surgical corpectomy. Spine J. 2006;6:S233-S241.

12. Zdeblick T.A., Hughes S.S., Riew K.D., Bohlman H.H. Failed anterior cervical discectomy and arthrodesis. Analysis and treatment of thirty-five patients. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1997;79:523-532.

13. Ryken T.C., Heary R.F., Matz P.G., et al. Cervical laminectomy for the treatment of cervical degenerative myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11:142-149.

14. Gok B., McLoughlin G.S., Sciubba D.M., et al. Surgical management of cervical spondylotic myelopathy with laminectomy and instrumented fusion. Neurol Res. 2009;31:1097-1101.

15. Anderson P.A., Matz P.G., Groff M.W., et al. Laminectomy and fusion for the treatment of cervical degenerative myelopathy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11:150-156.

16. Sekhon L.H. Posterior cervical decompression and fusion for circumferential spondylotic cervical stenosis: review of 50 consecutive cases. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:23-30.

17. Komotar R.J., Mocco J., Kaiser M.G. Surgical management of cervical myelopathy: indications and techniques for laminectomy and fusion. Spine J. 2006;6:S252-S267.

18. Houten J.K., Cooper P.R. Laminectomy and posterior cervical plating for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: effects on cervical alignment, spinal cord compression, and neurological outcome. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1081-1087. discussion 1087–1088

19. Wang M.Y., Green B.A. Open-door cervical expansile laminoplasty. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:119-123. discussion 123–124

20. Suda K., Abumi K., Ito M., et al. Local kyphosis reduces surgical outcomes of expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. 2003;28:1258-1262.

21. Petraglia A.L., Srinivasan V., Coriddi M., et al. Cervical laminoplasty as a management option for patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a series of 40 patients. Neurosurgery. 2010;67:272-277.

22. Kaner T., Sasani M., Oktenoglu T., Ozer A.F. Clinical outcomes following cervical laminoplasty for 19 patients with cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Turk Neurosurg. 2009;19:121-126.

23. Yukawa Y., Kato F., Ito K., et al. Laminoplasty and skip laminectomy for cervical compressive myelopathy: range of motion, postoperative neck pain, and surgical outcomes in a randomized prospective study. Spine. 2007;32:1980-1985.

24. Kaplan L., Bronstein Y., Barzilay Y., et al. Canal expansive laminoplasty in the management of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Isr Med Assoc J. 2006;8:548-552.

25. Kimura I., Shingu H., Nasu Y. Long-term follow-up of cervical spondylotic myelopathy treated by canal-expansive laminoplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1995;77:956-961.

26. Kotani Y., Cunningham B.W., et al. Biomechanical analysis of cervical stabilization systems. An assessment of transpedicular screw fixation in the cervical spine. Spine. 1994;19:2529-2539.

27. Jones E.L., Heller J.G., Silcox D.H., Hutton W.C. Cervical pedicle screws versus lateral mass screws. Anatomic feasibility and biomechanical comparison. Spine. 1997;22:977-982.

28. Kothe R., Ruther W., Schneider E., Linke B. Biomechanical analysis of transpedicular screw fixation in the subaxial cervical spine. Spine. 2004;29:1869-1875.

29. Johnston T.L., Karaikovic E.E., Lautenschlager E.P., Marcu D. Cervical pedicle screws vs. lateral mass screws: uniplanar fatigue analysis and residual pullout strengths. Spine J. 2006;6:667-672.

30. Hasegawa K., Hirano T., Shimoda H., et al. Indications for cervical pedicle screw instrumentation in nontraumatic lesions. Spine. 2008;33:2284-2289.

31. Abumi K., Shono Y., Taneichi H., et al. Correction of cervical kyphosis using pedicle screw fixation systems. Spine. 1999;24:2389-2396.

32. Abumi K., Shono Y., Ito M., et al. Complications of pedicle screw fixation in reconstructive surgery of the cervical spine. Spine. 2000;25:962-969.

Combined Ventral and Dorsal Approach

Cervical kyphosis may be the result of a variety of pathologies, including trauma, postsurgical instability, advanced degenerative disease, or systemic inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis.1 The most common cause of cervical deformity, however, is iatrogenic.2 Such may be secondary to either ventral or dorsal operations but is most commonly observed after multilevel dorsal decompression with rates of clinically significant kyphosis as high as 21%.3–5

If a kyphotic deformity is present, a flexion moment is created with the head pitched forward relative to the normal alignment of the cervical spine.2,6,7 The abnormal posture shifts the normally neutral axial force of the head ventrally to the instantaneous axis of rotation, thus creating a flexion bending moment.7 The ventral portions of the already compromised cervical vertebral bodies are therefore preferentially loaded and are prone to further kyphosis.2,7 Thus, a vicious cycle of abnormal forces and progressive deformity is created.2,6–8 If the kyphosis becomes severe, the spinal cord may be come stretched over the apex of the deformity with a resultant myelopathy.2,9 Moreover, kyphosis places the dorsal cervical musculature at a relative mechanical disadvantage, which along with continued disc degeneration can result in mechanical neck pain.2,10 Cervical kyphotic deformities should, therefore, be avoided. However, if a kyphotic deformity does develop, surgical intervention can be used to correct the deformity, stabilize the spine, and decompress the neural elements.

Dorsal versus Ventral versus Combined Approaches

Once a cervical deformity is present, and the decision is made for surgical intervention, three fundamental approaches are possible: dorsal,6,11 ventral,12–16 or a combination.1,6,17,18 A number of surgical procedures using the dorsal approach have been described in the literature, including simple laminectomy, various derivations of laminoplasty, and laminectomy augmented with dorsal fusion (with or without instrumentation).6,11 The advantages of the dorsal approach include familiarity, ease of decompression of multiple levels, and the ability to extend the fusion and/or fixation rostrally to the occiput and/or caudally to the thoracic spine. The major disadvantage of laminectomy and laminoplasty is the obligatory disruption of the dorsal tension-band, resulting in a high rate of postlaminectomy kyphosis.5,7 This complication has led some authors to caution against use of these procedures in patients with preexisting cervical kyphosis or even in the relative kyphosis of the “straightened” cervical spine.2,7,9,19 Moreover, ventral compression cannot be addressed from the dorsal approach. In some cases, the use of dorsal cervical fixation, in combination with dorsal decompression, may be used to correct a mild degenerative kyphosis.20 However, this technique requires the presence of a flexible deformity to facilitate correction of the kyphosis, without the aid of a ventral release.6 Needless to say, this situation is a rare occurrence in the degenerative spine. Furthermore, the degree of deformity correction achieved via an isolated dorsal strategy may be limited.6

A number of authors have advocated the use of a ventral approach for dealing with cervical myelopathy associated with kyphosis.12–1416 This approach affords the spine surgeon the ability to both address ventral compression, as well as perform a ventral release via corpectomy or multiple discectomies, prior to the actual correction of the cervical deformity. Moreover, because the majority of cervical kyphotic deformities are idiopathic and the result of prior dorsal procedures, use of a ventral strategy has the added benefit of avoiding much of the morbidity associated with revision surgery.3–5 Although, this strategy has been shown to be highly effective for patients with short-segment stenosis and kyphosis, historically high rates of pseudarthrosis, bone graft subsidence, and graft dislocation have been seen with long-segment or multisegment constructs.2,16 These complications are largely a manifestation of the often suboptimal bony fixation sites, the poor mechanical advantage, and the reliance on screw fixation as the only available method of bony fixation afforded by the ventral approach.7 Some of these factors may be mitigated by the use of intermediate points of fixation and by the introduction of dynamic implants, although their true effectiveness in this regard has yet to be proven.7 A purely ventral approach, much like the purely dorsal approach, neither permits access for dorsal decompression of the spinal cord nor affords the surgeon the ability to recreate the dorsal tension-band in patients who exhibit incompetent dorsal elements.

The use of a combined dorsal and ventral strategy affords all of the aforementioned advantages of each and limits the disadvantages of both approaches used alone. The surgeon is able to perform a 360-degree decompression and thereby address both dorsal and ventral neural compression. Optimal correction of sagittal plane cervical deformities can be achieved by making use of the mechanical advantage of dorsal constructs and osteotomies, in conjunction with ventral releases and reconstruction of the ventral load bearing column via interbody fusion techniques.7,17,21 This affords the spine surgeon the ability to both lengthen the ventral column and shorten the dorsal column to achieve an optimal correction. Moreover, in the ankylosed spine with a fixed deformity, it facilitates the releases of both dorsal and ventral elements necessary for deformity correction.17,21 Furthermore, the addition of dorsal fixation to a ventral construct may help further minimize the risk of pseudarthrosis by loading the construct via a compressive moment and provide further translational and torsional resistance.7,22,23 This may optimize fusion rates via Wolff’s law and may be especially useful in patients with poor bone quality, comorbidities, or prior failed surgeries. Lastly, a combined ventral and dorsal fusion strategy may obviate the need for external orthoses in many cases.17,22 The chief disadvantage of the combined approach has been the relative morbidity when compared with either purely dorsal or ventral strategies. Overall complication rates as high as 33% have been reported in the literature with circumfrential strategies for correction of cervical kyphosis.22,23 However, both Schultz et al.21 and McAfee et al.17 have reported acceptably low rates of complications and long-term morbidity (5% and 11%, respectively).

Buttler J.C., Whitecloud T.S.III. Postlaminectomy kyphosis: causes and surgical management. Clin Orthop North Am. 1992;23:505-511.

McAfee P.C., Bohlman H.H., Ducker T.B. One stage anterior cervical decompression and posterior stabilization. A study of one hundred patients with a minimum of two years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1995;77:1791-1800.

Mummaneni P.V., Dhall S.S., Rodts G.E., et al. Circumfrential fusion for cervical kyphotic deformity. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:515-521.

Nottmeier E.W., Deen H.G., Patel N., et al. Cervical kyphotic deformity correction using 360-degree reconstruction. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22(6):385-391.

Schultz K.D., McLaughlin M.R., Haid R.W., et al. Single-stage anterior-posterior decompression and stabilization for complex cervical spine disorders. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(Suppl 2):214-221.

1. Heller J.G., Silcox D.H.3rd, Sutterlin C.E.3rd. Complications of posterior cervical plating. Spine. 1995;20:2442-2448.

2. Albert T.J., Vacarro A. Postlaminectomy kyphosis. Spine. 1998;23:2738-2745.

3. Caspar W., Pitzen T. Anterior cervical fusion and trapezoidal plate stabilization for re-do surgery. Surg Neurol. 1999;52:345-352.

4. Geisler F.H., Caspar W., Pitzen T., et al. Reoperation in patients after anterior cervical plate stabilization in degenerative disease. Spine. 1998;23:911-920.

5. Kaptain G.J., Simmons N., Replogle R.E., Pobereskin L. Incidence and outcome of kyphotic deformity following laminectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(Suppl 2):199-204.

6. Abumi K., Shono Y., Taneichi H. Correction of cervical kyphosis using pedicle screw fixation systems. Spine. 1999;24:2389-2396.

7. Benzel E.C. Biomechanics of spine stabilization. Rolling Meadows, IL: American Association of Neurological Surgeons; 2001.

8. Masini M., Maranho V. Experimental determination of the effect of progressive sharp-angle spinal deformity on spinal cord. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:89-92.

9. Kimura I., Shingu H., Nasu Y. Long-term follow-up of cervical spondylotic myelopathy treated by canal expansive laminoplasty. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1995;77:956-961.

10. Katsuura A., Hukuda S., Imanaka T., et al. Anterior cervical plate used in degenerative disease can maintain cervical lordosis. J Spinal Disord. 1996;9:470-476.

11. Callahan R.A., Johnson R.M., Margolis R.N. Cervical facet fusion for control of instability following laminectomy. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1977;59:991-1002.

12. Buttler J.C., Whitecloud T.S.III. Postlaminectomy kyphosis: causes and surgical management. Clin Orthop North Am. 1992;23:505-511.

13. Cattrell H.S., Clark G.J.Jr. Cervical kyphosis and instability following multiple laminectomies in children. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1967;49:713-720.

14. Herman J.M., Sonntag V.K. Cervical corpectomy and plate fixation for post-laminectomy kyphosis. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:963-970.

15. Zdeblick T.A., Bohlman H.H. Cervical kyphosis and myelopathy: treatment by anterior corpectomy and strut-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1989;71:170-182.

16. Zdeblick T.A., Hughes S.S., Riew K.D., et al. Failed anterior cervical discectomy and arthrodesis: analysis and treatment of thirty-five patients. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1997;79:523-532.

17. McAfee P.C., Bohlman H.H., Ducker T.B. One stage anterior cervical decompression and posterior stabilization. A study of one hundred patients with a minimum of two years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1995;77:1791-1800.

18. Savini R., Parisini P., Cervellati S. The surgical treatment of late instability of flexion-rotation injuries in the lower cervical spine. Spine. 1987;12:178-182.

19. Suda K., Abumi K., Ito M., et al. Local kyphosis reduces surgical outcomes of expansive open door laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. 2003;28:1258-1262.

20. Abumi K., Kaneda K., Shono Y., et al. One-stage posterior decompression and reconstruction of the cervical spine by using pedicle screw fixation systems. J Neurosurg. 1999;90:19-26.

21. Schultz K.D., McLaughlin M.R., Haid R.W., et al. Single-stage anterior-posterior decompression and stabilization for complex cervical spine disorders. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(Suppl 2):214-221.

22. Mummaneni P.V., Dhall S.S., Rodts G.E., Haid R.W. Circumfrential fusion for cervical kyphotic deformity. J Neurosurg Spine. 2008;9:515-521.

23. Nottmeier E.W., Deen H.G., Patel N., Birch B. Cervical kyphotic deformity correction using 360-degree reconstruction. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22:385-391.