Chapter 202 Spine Reoperations

Preventing repeat spine surgery is an important goal for surgeons and their patients. Reoperation is generally an undesirable outcome, implying persistent symptoms, progression of the underlying disease, or complications related to the initial operation. A higher risk of reoperation was observed among patients covered by workers’ compensation insurance compared with those with other types of insurance. Patients under age 60 were more likely than those age 60 years and older to have second operations. Males had a slightly lower risk of reoperation than females, and having any comorbidity resulted in a higher risk of reoperation.1

Patients undergoing surgery for degenerative spine disease may require further surgery for disease progression at the original operative level or at adjacent levels or for instability. Reoperation has proven to be much less effective than initial surgery, and it is estimated that only 30% to 50% of patients benefit from this second surgical procedure. Reoperation rate varies with the region of the spinal column, type of disease, and type of previous surgery. Reoperations are performed at the rate of 2.5% per year at the cervical spine level and range from 8.9% to 10.2% at the lumbar level. Reoperations are more expensive; a recent study found that the average hospital charge for a cervical spine reoperation is $57,205.2 Identifying modifiable factors, such as the choice of approach, might reduce the need for spine reoperations and might improve public health and curb health care expenditures.

Neural Compression

The most common reason for reoperation on the spine is recurrent or persistent neural compression. Of all the indications for reoperation for neural compression, recurrent or persistent radiculopathy (radiculitis secondary to disc or scar) is by far the most common.3–11 Persistent symptoms with neural compression are seen in patients with a recurrent disc herniation, large foraminal osteophyte, thickened ligamentum flavum, facet joint hypertrophy causing root compression and inadequate decompression of the spinal cord or cauda equina in spinal stenosis, calcified nerve, ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament, recurrent disc herniation, or neoplasia.12,13

Lumbar Radiculopathy or Radiculitis

The reported incidence of symptomatic recurrent disc herniation after lumbar discectomy varies between 3% and 18% in retrospective studies.14 Subjects with larger anular defects and those in whom a smaller proportion of disc volume was removed during the first surgery were associated with an increased risk of symptomatic recurrent disc herniation. Carragee et al. demonstrated that the reherniation rate varied from 1.1% with small fissure-like anular defects to 27.3% for large open anular defects.15 Recurrent disc herniation or progressive disc space loss after discectomy often leads to increased pain and disability, which necessitates repeat surgery. Revision surgery, however, does not always improve symptoms.16 The differentiation of a recurrent disc herniation from an epidural scar presents a dilemma. Characteristics associated with recurrent disc herniation include a nonenhanced or rim-enhanced abnormality surrounding a low-signal-intensity lesion on MRI and extension of contrast into the epidural space and an enhancing abnormality on CT/discography.17 However, the discovery of a focal mass of scar that is obviously compressing a nerve root may still be an indication for surgery. Diffuse epidural scar without nerve root compression, however, is not.

Inadequate Decompression of the Cauda Equina in Spinal Stenosis

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a complex of clinical symptoms and signs most commonly secondary to a massive prolapsed intervertebral disc, accounting for 2% to 6% of all lumbar disc herniations. Less common causes of CES are epidural hematoma, infections, primary and metastatic neoplasms, trauma, and prolapse after manipulation, chemonucleolysis, or spinal anesthesia. Meta-analysis of surgically treated CES suggests benefit if decompression is undertaken within 48 hours from symptom onset18 in pooled data from retrospective studies. However, not all studies support this argument, which has raised the notion that the principal determinant of outcome may be not timing, but the extent of the neurologic deficit before surgery.19

Recurrent symptoms of CES occur not only from inadequate previous decompression but also from progression of the disease. The most common radiographic findings are disc herniation and hypertrophic facet arthritis, whereas other features, such as acquired spondylolisthesis, osteophyte formation, stenosis, and scoliosis, are observed less frequently. The pathophysiology remains unclear but may be related to damage to the nerve roots composing the cauda equina from direct mechanical compression and venous congestion or ischemia. A high index of suspicion is necessary in the postoperative spine patient with back or leg pain refractory to analgesia, especially in the setting of urine retention. Regardless of the setting, when CES is diagnosed, the treatment is urgent surgical decompression of the spinal canal.

Recurrence and Inadequate Decompression of the Spinal Cord in Neoplasia

Reoperation for intramedullary tumors needs a special mention. With advances in microsurgical technology, management of these tumors has shifted toward aggressive treatment with radical resection. This approach is associated with increased long-term survival and improved quality of life for both intramedullary and extramedullary tumors. Spine deformity, a well-documented complication after intradural spinal tumor resection, has been reported in up to 10% of cases in adults and 22% to 100% of cases in children.20,21 Laminoplasty for the resection of intradural spinal tumors is not associated with a decreased incidence of short-term progressive spinal deformity or improved neurologic function. However, laminoplasty may be associated with a reduction in incisional CSF leak.22

Instability

Extrusion of a bone graft, failure of fusion, the development of instability, or failure of instrumentation is an indication for reoperation.12,13,23–35

Extrusion of a Bone Graft

The extruded bone fragment is removed, the graft site is freshened, usually by use of a high-speed drill to accomplish good preparation of the end plates, and a new graft is inserted. A ventral plate-and-screw construct provides further assurance of retention of the bone graft. High reoperation rates for extruded grafts and symptomatic pseudarthrosis have been associated with nonplated two-level anterior discectomy and fusion (ADF) and single-level anterior corpectomy with fusion (ACF) procedures. However, comparison of single-level ACF performed with and without plates showed that plating did not appear to reduce pseudarthrosis or graft extrusion rates.36 If the vertebral body is fractured as well, partial corpectomy of the fractured segment must be performed and the graft refitted. This necessitates a longer graft. Ventral plating with screw fixation may add to the stability of the new construct. A supplement to fixation via a dorsal approach should often be considered.

Failure of Fusion

The ultimate goal of spinal hardware is to provide temporary stability allowing for bony fusion, usually requiring 6 to 9 months. Failure of fusion and the development of pseudarthrosis or fibrous union are the sequelae of ongoing low-grade mobility. Pseudarthrosis is defined as an absence of bridging bone between grafted bone and vertebral bodies and the presence of a radiolucent defect, a halo sign, or a loss of grafted bone. Despite advances in the technologies and instrumentation of spine surgery, pseudarthrosis still occurs in 10% to 15% of all patients.37 Pseudarthrosis itself can be a source of pain, or it may provide a lead point for ongoing mobility leading to increased stress on hardware and inevitable failure, one of the indications for reoperation. Revision spinal arthrodesis for pseudarthrosis and loose instrumentation with widely dilated screw tracts is a difficult clinical problem.

The optimal revision strategy in cases of lumbar pseudarthrosis depends on the specific clinical scenario, and multiple techniques have been described. If stable fixation cannot be achieved in these cases, revision fusion may fail, or adjacent normal levels may need to be fused to gain stable fixation. According to the latest Cochrane review,38 pedicle screw instrumentation produces a higher fusion rate, but any improvement in clinical outcome is probably marginal as compared to fusion without instrumentation.

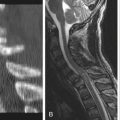

Single-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) is a highly successful procedure yielding high reported fusion rates, ranging from 83% to 97% for autograft and 82% to 94% for allograft, respectively. However, in multilevel ACDF, as the number of grafts increases, the cervical spine is predisposed to decreased fusion rates as contact stress increases between the graft–body interface, further contributing to unacceptable micromotion. Pseudarthrosis after ACDF has been recognized as a cause of continued cervical pain and unsatisfactory outcomes. Debate continues as to whether a revision ventral approach or a dorsal fusion procedure is the best treatment for symptomatic cervical pseudarthrosis. Patients with symptomatic cervical pseudarthrosis that develops after ACDF may be managed successfully with dorsal lateral mass screw fixation and fusion. The rationale for the dorsal approach includes the advantages of avoiding the scar tissue and potentially difficult tissue planes encountered in a revision ventral approach, as well as encountering a fresh fusion bed when a dorsal approach is used. Contraindications to the dorsal approach include those problems that can only be addressed through a ventral approach, such as graft migration or kyphosis. Advocates for a revision ventral approach suggest that patients experience more stiffness and pain after a dorsal approach secondary to disruption of the dorsal musculature.39

Development of Instability

Kyphosis may develop in up to 21% of patients who have undergone laminectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Progression of the deformity appears to be more than twice as likely if preoperative radiologic studies demonstrate a straight spine. The incidence of progressive deformity and instability after cervical laminectomy was highest in the pediatric population and in those with a malignant intramedullary lesion, adjuvant radiotherapy, or preoperative findings of kyphosis or instability. Other intraoperative factors, including resection of the C2 lamina, multilevel laminectomies (>3 levels removed), and removal of greater than 25% of the facet joint, have also been correlated with an increased risk for subsequent development of deformity, instability, and neurologic sequelae. Although cervical laminoplasty has been proposed to reduce the risk of postsurgical deformity, recent reports suggest no significant reduction in the incidence of spine deformity, especially in the setting of intradural spinal tumor resection.22,40

Late failures in lumbar spinal stenosis may be due to persistent or acquired instability, recurrence of stenosis at operated levels, new stenosis at adjacent levels, epidural fibrosis, or arachnoiditis. Degenerative discogenic pain and reports of narrowing of the intervertebral disc space, reactive changes in adjacent vertebral bodies, vacuum disc phenomenon, spondylolisthesis (ventral or dorsal), and abnormal motion of 3 mm or more on flexion-extension radiographs are all indicative of lumbar instability.41 The development of postoperative intraspinal facet cysts has been related to the presence of postoperative segmental spinal instability, including a progression of spondylolisthesis and disc degeneration. Pedicle screw fixation fusion with interbody fusion gives better results in postoperative spinal instability. Dorsal closing wedge osteotomy is suitable to treat kyphosis of less than 40 degrees. Ventral release and dorsal spinal osteotomy is effective, especially in patients with severe kyphotic deformity or with previous surgery.

Failure of Instrumentation

Assessment of spinal hardware often involves a multimodality approach, including nuclear medicine, CT, and MRI, but plain radiographs are an essential component that can provide information other modalities cannot. Changes in component position, bony alignment, hardware fractures, and changes in the implant–bone interface (e.g., screw loosening with haloing) can be first identified and sometimes best appreciated on serial radiographs.42 Hardware fracture generally occurs secondary to metal fatigue from repetitive stress. The presence of a fracture is frequently associated with regional motion and instability, which may lead to or result from pseudarthrosis.43 Hardware failure includes hardware fracture, loosening of the screws, and screw pullout leading to junctional failure. Hardware loosening can be caused by osseous resorption surrounding screws and implants. Loosening in turn allows for movement, which causes further osseous resorption, increased mobility, and eventually catastrophic screw pullout or vertebral fractures.44,45 Serial radiographs, starting from the earliest postoperative study, should be evaluated for any evidence of hardware migration or fracture. Identification of a change in sagittal or coronal balance is often a valuable initial step. Set-screw loosening, rod fatigue bending without frank fracture, and sacral screw subsidence are subtle abnormalities that should also be carefully examined in patients with late postoperative loss of sagittal alignment.46

A review of the literature noted a 28.1% to 39.9% rate of pedicle screw malposition in clinical studies and a 5.5% to 31.3% malposition rate in cadaver studies. However, meta-analysis shows that only 0.6% to 4.3% of patients need reoperations for device malposition.47 The percentage of malpositioned screws may be higher when normal anatomic landmarks have been obscured, as with revision surgery in the setting of a dorsolateral fusion.48 Minor violations of the cortex are not uncommon and may be asymptomatic. In these cases, the screw position may be acceptable. Screw malposition with related clinical symptoms needs revision surgery. Pedicle screw loosening has been recorded as being caused mainly by cyclic caudocephalad toggling at the bone–screw interface. To prevent pedicle screw loosening, a meticulous screw insertion technique to prohibit the toggling effect that could be occurring during screw insertion is needed. On reoperation, a larger-diameter screw or augmentation with polymethylmethylacrylate (PMMA) gives a better result.

Cerebrospinal Fluid Leak

Reoperation for CSF leak requires adequate exposure of the dural defect, which may require further bone removal. Primary closure is attempted whenever possible. A patch of autologous fascia or artificial dura material with fibrin tissue adhesive is useful if primary closure is not possible.49–51 Black52 used a large sheet of fat to cover not only the dural tears but also all of the exposed dura with good results. A randomized, controlled trial concluded that the PEG hydrogel spinal sealant (DuraSeal) is safe and effective for providing watertight closure when used as an adjunct to sutured dural repair during spinal surgery.53 Placement of a CSF drain for 5 days may be used for dural repair if primary dural closure fails. Good muscle and fascia closure will prevent dead space and prevent CSF collection and postoperative pseudomeningocele. In recurrent CSF leak, myocutaneous muscle flaps can be considered an option with good results.

Infection

Surgical site infection in the setting of spine fusion is associated with significant morbidity and medical resource utilization. The reported rate of spinal surgical site infection in the literature ranges from 0.7% to 16 %.54,55 Risk factors include smoking, diabetes, prolonged operative time, large-volume blood loss, previous surgery, use of nonautograft bone graft alternatives, and number of levels affected. Spinal surgical site infections can be challenging to manage and often require prolonged hospitalizations, extended antibiotic therapy, repeated surgery for wound debridement, instrumentation removal, or delayed complications of deep infection. It is often difficult to diagnose postoperative spine infection before clinical symptoms become apparent. In the early stages, plain film radiography is often normal. In this setting, nuclear scintigraphy with either gallium-labeled bone scan or indium-111-labeled white blood cells or MRI can be useful. MRI can help to diagnose the soft tissue change but is expensive to use as a screening tool. Although inflammatory markers, such as C-reactive protein (CRP), white blood cell count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and body temperature are easily measured, their specificities are not high. Elevated serum procalcitonin levels of greater than 0.5 ng/mL may serve as a useful tool for evaluating fevers of unknown origin after spine surgery.56

Reoperation for wound infection is best handled by reopening the complete length of the incision to the depth of infectious involvement. After all suture material is removed, along with any dead tissue, the wound is debrided to bleeding tissue. The wound should then be irrigated thoroughly with antibiotic solution. If the infection is superficial, the wound is closed in layers, and the patient is given appropriate intravenous antibiotics to which the organism is susceptible. For deep infections and for infections in the presence of instrumentation or bone grafts, a similar procedure is carried out, or staged closure with wound vacuum is helpful. If osteomyelitis or discitis is present, debridement of the involved bone and disc is performed via a retroperitoneal or dorsal-only approach in the lumbar spine, a lateral extracavitary approach in the thoracic spine, and a ventral or dorsal approach in the cervical spine. A fresh autologous cortical bone graft is inserted for ventral stabilization. Unlike in joint arthroplasty, hardware removal is not mandatory to eradicate most infections, although removal of the hardware may be indicated in certain cases in which medical treatment has failed, especially if the infection is delayed and fusion is solid.42,57 The antibiotics are usually continued for 6 weeks or even longer if the CRP level has not returned to normal by that time.

Hematomas

Spinal epidural hematoma is a known complication of spine surgery. Most surgical procedures involving the spine will result in a small, clinically insignificant epidural hematoma. However, some spinal epidural hematomas are significant enough to cause spinal cord compression and neurologic symptoms requiring surgical intervention. Postoperative epidural hematomas should be suspected in the patient who either demonstrates a new postoperative neurologic deficit or develops deficits in the immediate postoperative period. Lawton et al.58 reported the incidence rate of spinal epidural hematomas to be 0.1%. Spinal epidural hematoma is a significant cause of morbidity and needs to be diagnosed as early as possible because the timing of decompression and evacuation of the hematoma is critical. Extra precautions for meticulous hemostasis during the surgical procedure should be considered in patients who require multilevel decompressions or have a preoperative coagulopathy. Placement of a postoperative wound drain to prevent epidural hematoma is still controversial.

Ahn U.M., Ahn N.U., Buchowski M.S., et al. Cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation. A meta-analysis of surgical outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1515-1522.

Berquist T.H. Imaging of the postoperative spine. Radiol Clin North Am. 2006;44(3):407-418.

Carragee E.J., Han M.Y., Suen P.W., et al. Clinical outcomes after lumbar discectomy for sciatica: the effects of fragment type and anular competence. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2003;85:102-108.

Lawton M.T., Porter R.W., Heiserman J.E., et al. Surgical management of spinal epidural hematoma: relationship between surgical timing and neurological outcome. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:1-7.

Martin B.I., Mirza S.K., Comstock B.A., et al. Are lumbar spine reoperation rates falling with greater use of fusion surgery and new surgical technology? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(19):2119-2126.

McGirt M.J., Ambrossi G.L., Datoo G., et al. Recurrent disc herniation and long-term back pain after primary lumbar discectomy: review of outcomes reported for limited versus aggressive disc removal. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(2):338-345.

McGirt M.J., Garces-Ambrossi G.L., B.S., Parker S.L., et al. Short-term progressive spinal deformity following laminoplasty versus laminectomy for resection of intradural spinal tumors: analysis of 238 patients. Neurosurgery. 2010;66(5):1005-1012.

1. Martin B.I., Mirza S.K., Comstock B.A., et al. Are lumbar spine reoperation rates falling with greater use of fusion surgery and new surgical technology? Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007;32(19):2119-2126.

2. Ghogawala Z: Ventral surgery versus dorsal decompression with fusion of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: a cost analysis (abstract), 76th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 2008, Chicago.

3. Cauchoix J., Ficat C., Girard B. Repeat surgery after disc excision. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1978;3:256-259.

4. Ebeling U., Kalbarcyk H., Reulen H.J. Microsurgical reoperation following lumbar disc surgery: timing, surgical findings, and outcome in 92 patients. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:397-404.

5. Echlin F.A., Selverstone B., Scribner W.E. Bilateral and multiple ruptured discs as one cause of persistent symptoms following operation for a herniated disc. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1946;83:485-493.

6. Finnegan W.J., Fenlin J.M., Marvel J.P., et al. Results of surgical intervention in the symptomatic multiply-operated back patient: analysis of 67 cases followed for 3 to 7 years. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1979;61:1077-1081.

7. Frymoyer J.W., Matteri R.E., Hanley E.N., et al. Failed lumbar disc surgery requiring second operation: long-term follow-study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1978;3:7-11.

8. Hardy R.W. Repeat operation for lumbar disc. In: Hardy R.W., editor. Lumbar disc disease. New York: Raven; 1982:193-202.

9. Law J.D., Lehman R.A.W., Kirsch W.M. Reoperation after lumbar intervertebral disc surgery. J Neurosurg. 1978;48:259-263.

10. Martin G. Recurrent disc prolapse as a cause of recurrent pain after laminectomy for lumbar disc lesions. N Z Med J. 1980;91:206-208.

11. Silvers H.R., Lewis P.J., Asch H.L., Clabeaux D.E. Lumbar diskectomy for recurrent disc herniation. J Spinal Disord Tech. 1994;7:408-419.

12. Katz J.N., Lipson S.J., Larson M.G., et al. The outcome of decompressive laminectomy for degenerative lumbar stenosis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1991;73:809-816.

13. Tuite G.F., Stern J.D., Doran S.E., et al. Outcome after laminectomy for lumbar spinal stenosis. Part I. Clinical correlations. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:699-706.

14. McGirt M.J., Ambrossi G.L., Datoo G., et al. Recurrent disc herniation and long-term back pain after primary lumbar discectomy: review of outcomes reported for limited versus aggressive disc removal. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(2):338-345.

15. Carragee E.J., Han M.Y., Suen P.W., et al. Clinical outcomes after lumbar discectomy for sciatica: the effects of fragment type and anular competence. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2003;85:102-108.

16. Vik A., Zwart J.A., Hulleberg G., Nygaard O.P. Eight-year outcome after surgery for lumbar disc herniation: a comparison of reoperated and not reoperated patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2001;143(6):607-611.

17. Bernard T.N.Jr. Using computed tomography/discography and enhanced magnetic resonance imaging to distinguish between scar tissue and recurrent lumbar disc herniation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1994;19(24):2826-2832.

18. Ahn U.M., Ahn N.U., Buchowski M.S., et al. Cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation. A meta-analysis of surgical outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1515-1522.

19. Gleave J.R.W., Macfarlane R. Cauda equina syndrome: what is the relationship between timing of surgery and outcome? Br J Neurosurg. 2002;16(4):325-328.

20. Yeh J.S., Sgouros S., Walsh A.R., Hockley A.D. Spinal sagittal malalignment following surgery for primary intramedullary tumours in children. Pediatr Neurosurg. 2001;35(6):318-324.

21. De Jonge T., Slullitel H., Dubousset J., et al. Late-onset spinal deformities in children treated by laminectomy and radiation therapy for malignant tumours. Eur Spine J. 2005;14(8):765-771.

22. McGirt M.J., Garcés-Ambrossi G.L., Parker S.L., et al. Short-term progressive spinal deformity following laminoplasty versus laminectomy for resection of intradural spinal tumors: analysis of 238 patients. Neurosurgery. 2010;66(5):1005-1012.

23. Andrew T.A., Brooks S., Piggott H. Long-term follow-up evaluation of screw-and-graft fusion of the lumbar spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1986;203:113-119.

24. Brodsky A.E., Khalil M.A., Sassard W.R., Newman B.P. Repair of symptomatic pseudarthrosis of anterior cervical fusion: posterior versus anterior repair. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992;17:1137-1143.

25. Farey I.D., McAfee P.C., Davis R.F., Long D.M. Pseudarthrosis of the cervical spine after anterior arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1990;72:1171-1177.

26. Grubb S.A., Lipscomb H.J. Results of lumbosacral fusion for degenerative disc disease with and without instrumentation: two- to five-year follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1992;17:349-355.

27. Hartman J.T., McCarron R.F., Robertson W.W.Jr. A pedicle bone grafting procedure for failed lumbosacral spinal fusion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;178:223-227.

28. Herkowitz H.N., Kurz L.T. Degenerative lumbar spondylolisthesis with spinal stenosis: a prospective study comparing decompression with decompression and intertransverse process arthrodesis. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1991;73:802-808.

29. Jackson R.K., Boston D.A., Edge A.J. Lateral mass fusion: a prospective study of a consecutive series with long-term follow-up. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1985;10:828-832.

30. Mutoh N., Shinomiya K., Furuya K., et al. Pseudarthrosis and delayed union after anterior cervical fusion. Int Orthop. 1993;17:286-289.

31. Newman M. The outcome of pseudarthrosis after cervical anterior fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993;18:2380-2382.

32. Shinomiya K., Okamoto A., Kamikozuru M., et al. An analysis of failures in primary cervical anterior spinal cord decompression and fusion. J Spinal Disord Tech. 1993;6:277-288.

33. West J.L.III, Bradford D.S., Ogilvie J.W. Results of spinal arthrodesis with pedicle screw-plate fixation. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1991;73:1179-1184.

34. Wetzel F.T., LaRocca H. The failed posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991;16:839-845.

35. Zindrick M.R. The role of transpedicular fixation systems for stabilization of the lumbar spine. Orthop Clin North Am. 1991;22:333-344.

36. Epstein N.E. Reoperation rates for acute graft extrusion and pseudarthrosis after one-level anterior corpectomy and fusion with and without plate instrumentation: etiology and corrective management. Surg Neurol. 2001;56:73-81.

37. Zdeblick T.A. A prospective, randomized study of lumbar fusion. Preliminary results. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993;18:983-991.

38. Gibson J.N., Waddell G. Surgery for degenerative lumbar spondylosis: updated Cochrane Review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:2312-2320.

39. Kuhns C.A., Geck M.J., Wang J.C., Delamarter R.B. An outcomes analysis of the treatment of cervical pseudarthrosis with posterior fusion. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(21):2424-2429.

40. Kaptain G.J., Simmons N.E., Replogle R.E., Pobereskin L. Incidence and outcome of kyphotic deformity following laminectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(Suppl 2):199-204.

41. Knutsson F. The instability associated with disk degeneration in the lumbar spine. Acta Radiol. 1944;25:593-609.

42. Berquist T.H. Imaging of the postoperative spine. Radiol Clin North Am. 2006;44(3):407-418.

43. Heller J.G., Whitecloud T.S., Butler J.C., et al. Complications of spinal surgery. In: Rothman R.R., Simeone F.A., editors. The spine. ed 3. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1992:1817-1898.

44. Kim P.E., Zee C.S. Imaging of the postoperative spine: cages, prostheses, and instrumentation. Spinal Imaging Med Radiol. 2007;6:397-413.

45. Tehranzadeh J., Ton J.D., Rosen C.D. Advances in spinal fusion. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2005;26(2):103-113.

46. Venu V., Vertinsky A.T., Malfair D., et al. Plain radiograph assessment of spinal hardware. Semin Musculoskel Radiol. 2011;15(2):151-162.

47. Hicks J.M., Singla A., Shen F.H., Arle V. Complications of pedicle screw fixation in scoliosis surgery. A systematic review. Spine. 2010;35(11):E465-E470.

48. Austin M.S., Vaccaro A.R., Brislin B., et al. Image-guided spine surgery; a cadaver study comparing conventional open laminoforaminotomy and two image-guided techniques for pedicle screw placement in posterolateral fusion and nonfusion models. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2002;27:2503-2508.

49. Cain J.E.Jr., Rosenthal H.G., Broom M.J., et al. Quantification of leakage pressures after durotomy repairs in the canine. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1990;15:969-970.

50. Gibble J.W., Ness P.M. Fibrin glue: the perfect operative sealant? Transfusion. 1990;30:741-747.

51. Stechison M.T. Rapid polymerizing fibrin glue from autologous or single donor blood: preparation and indications. J Neurosurg. 1992;76:626-628.

52. Black P. Cerebrospinal fluid leaks following spinal surgery: use of fat grafts for prevention and repair. Technical note. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(Suppl 2):250-252.

53. Kim K.D., Wright N.M. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) hydrogel spinal sealant (DuraSeal Spinal Sealant) as an adjunct to sutured dural repair in the spine: results of a prospective, multicenter, randomized controlled study. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2011;36(23):1906-1912.

54. Beiner J.M., Grauer J., Kwon B.K., et al. Postoperative wound infections of the spine. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E14.

55. Barker F.G. 2nd: Efficacy of prophylactic antibiotic therapy in spinal surgery: a meta-analysis. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:391-401.

56. Chung Y.G., Won Y.S., Kwon Y.J., et al. Comparison of serum CRP and procalcitonin in patients after spine surgery. J Korean Neurosurg Soc. 2011;49:43-48.

57. Young P.M., Berquist T.H., Bancroft L.W., Peterson J.J. Complications of spinal instrumentation. Radiographics. 2007;27(3):775-789.

58. Lawton M.T., Porter R.W., Heiserman J.E., et al. Surgical management of spinal epidural hematoma: relationship between surgical timing and neurological outcome. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:1-7.