Chapter 186 Spinal Traction

Spinal traction produces a longitudinal force along the spine that can aid in the stabilization of the spine, and in the reduction of deformity. Spinal traction is most commonly used for cervical pathology because there is little evidence to support the use of traction for lumbar pathology.1

History

Hippocrates described the use of traction for the reduction of vertebral dislocation more than 2000 years ago,2 but the modern era of traction started with the use of a halter device by Taylor in 1929 to reduce a cervical dislocation.3 In 1933, Crutchfield introduced the use of tongs inserted into the skull, and this method forms the basis for the current practice of skeletal traction.4 Crutchfield’s tongs were placed near the vertex of the skull and thus were prone to dislodgement if greater than 30 pounds of weight was applied. In 1973 the Gardner-Wells tongs were introduced, which are designed so that pins are placed below the equator of the skull and thus have greater resistance to pull-out.5 The halo device, which uses four pins for skull fixation, was described for use in skeletal traction by Nickel et al.6

Head Halter Traction

Head halter traction is often used as a component of nonsurgical treatment of painful manifestations of cervical spondylosis, including neck pain and radiculopathy. This is usually done on an outpatient basis and often as part of a home program. The patient typically uses up to 10 pounds of weight attached for several sessions per day. The effectiveness of this treatment is uncertain: a systematic review of published series found some evidence to suggest a benefit, but the methodological quality of the studies was felt to be poor.7

Head halter traction has been used for the reduction of atlantoaxial rotatory subluxation in pediatric patients. Subach et al. used halter traction to reduce atlantoaxial subluxation in a series of patients ranging in age from 3 to 11 years. They were able to achieve reduction in over 90% of patients; the mean amount of weight used was 4 pounds and the mean length of time necessary to achieve reduction was 4 days.8

Gardner-Wells Tongs

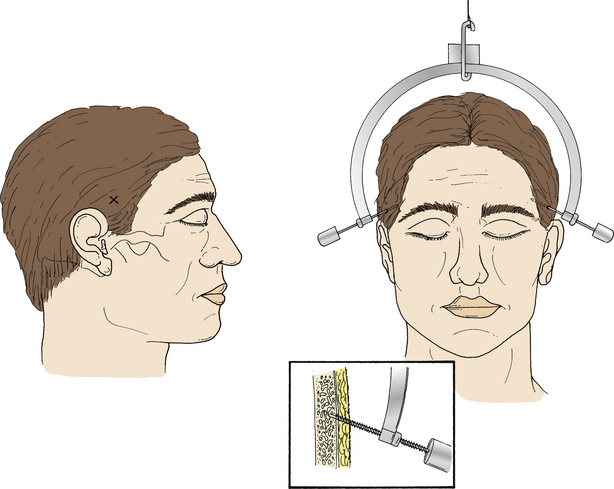

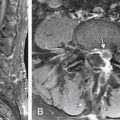

The Gardner-Wells tongs consist of a C-shaped rectangular rod with an S-shaped link in the center to which the application rope is applied. At each end of the C that arches over the head are threaded bolts with sharp, pointed tips. The pins should be placed through the outer table of the calvarium but should not penetrate the inner table. On one pin is a spring device that protrudes 1 mm when the appropriate amount of tension is applied to penetrate the outer table of the calvarium (Fig. 186-1).

The pins of the tongs are placed below the equator of the calvarium and 2 to 3 cm above the ears. The location of the pins varies, depending on whether traction is desired with the cervical spine in the neutral, flexed, or extended position. A fixation point that is on a line from the tip of the mastoid process to the tip of the pinna results in traction in the neutral orientation. If a site is selected ventral to this point, traction will be applied in extension; conversely, if the site selected is dorsal, the result will be traction with the spine in flexion. Alternatively, the amount of extension or flexion can be changed by altering the height of the pulley, which will alter the angle of the traction line: if the pulley is raised, flexion is usually achieved, and if the pulley is lowered, extension usually results.

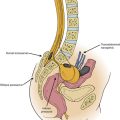

Cranial Halo

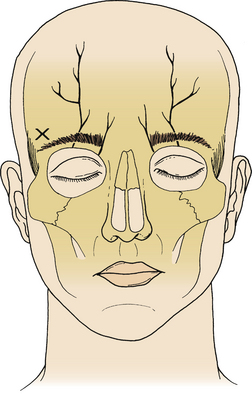

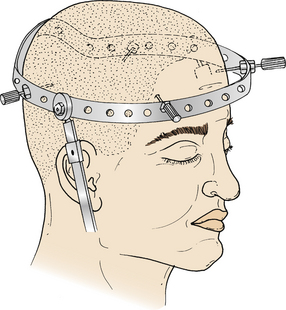

For application of the halo ring, the patient is positioned supine. The use of a mild sedative can be helpful to minimize patient anxiety during the procedure. Halo rings are available in several sizes, and the head circumference should be measured; ideally there should be about 1 to 1.5 cm of clearance between the skull and the halo ring. The halo pins have a broad base and a narrow tip to prevent penetration beyond the outer table of the skull. Four proposed pin sites are chosen. The ventral pin sites are located approximately 1 cm above the lateral third of the eyebrows to avoid injury to the supraorbital nerve (Figs. 186-2 and 186-3). The dorsal pins are diagonally opposite the ventral pins, approximately 1.5 cm above the ears. The selected areas are shaved and prepped with povidine-iodine, and 1% lidocaine is infiltrated into the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and periosteum. It is helpful to have an assistant available to hold the halo ring in position while the pins are inserted. Hexagonal lock nuts should be placed outside the ring before advancing the pin. The pins are threaded through the ring and advanced until the outer layer of the dermis is penetrated; the pins should be perpendicular to the skull. To prevent the halo from shifting during insertion, one ventral pin and the diagonally opposite dorsal pin are tightened simultaneously, followed by simultaneous tightening of the remaining ventral and dorsal pins. Once the pins have engaged the outer table of the skull, the diametrically opposite pins are tightened alternately with a torque wrench to 8 inch-pounds. The hexagonal nuts are then tightened against the halo ring, securing the position of the pins and preventing backing out of the pins. Twenty-four hours later, the hexagonal nuts should be loosened and the skull pins retorqued to 8 inch-pounds using the torque wrench, and then the hexagonal nuts are retightened. Daily pin care is important in preventing infection; this can be done with daily swabbing of the pin sites with dilute hydrogen peroxide.

The two most common problems with the halo pin sites are loosening and infection.9 Pin loosening has been postulated to be due to bone restoration underneath the pin.10 The pin can be retorqued to 8 inch-pounds as long as resistance is felt as the pin is being tightened11; if there is no resistance, the pin should be removed and a new pin placed in a new site. Infection at the pin site can present as erythema, swelling, or drainage at the pin site. Minor degrees of erythema can be treated with antibiotics and the pin left in place. If the erythema fails to respond or worsens, the pin should be removed and a new pin placed in a new site.

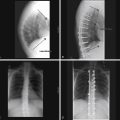

Reduction of Fracture-Dislocations

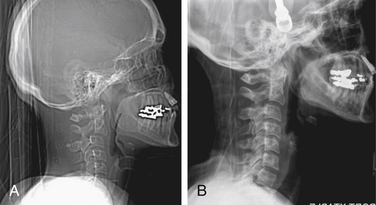

The reduction of these injuries can be achieved through the application of skeletal traction (Fig. 186-4) or alternatively by open reduction through either a ventral or dorsal approach. There have been several large case series of patients with facet dislocations reduced with traction.12–16 The advantage of traction is that reduction can be achieved relatively rapidly with the patient awake so that neurologic function can be monitored as the reduction is achieved. It should be noted, however, that some patients with facet dislocations are not able to participate in a careful neurologic examination due to intoxication or other injuries, and some facet dislocations simply cannot be reduced with closed techniques.

A baseline neurologic examination and lateral radiograph should be obtained before traction is applied. Because facet dislocations are principally flexion injuries, application of the tongs with the pins dorsal to the line between the mastoid and the pinna results in flexion of the neck as the force is applied, which may make reduction easier. Application of weight should begin with 5 pounds, and a repeat examination and lateral radiograph should be obtained; the radiograph should be examined for alignment as well as evidence for distraction. Distraction can cause neurologic injury, especially if there is an unrecognized more rostral injury. An indication of distraction is the presence of widening of the disc space by more than 5 mm. If this is detected, the weight should be removed and further attempts at closed reduction should be abandoned. If the neurologic examination is stable and there is no distraction on the radiograph, weight is added in 10-pound increments, repeating the examination and radiograph after each increase in weight. The examination should evaluate motor and sensory function but also pain level. The total amount of weight that should be used is uncertain. Crutchfield’s original recommendation was for no more than 5 pounds per vertebral level, but some authors have advocated higher weights, even up to 150 pounds of total traction.15 Traction tongs tolerate a large amount of weight: cadaver studies suggest that stainless steel Gardner-Wells tongs can tolerate up to 200 pounds before pulling out and titanium tongs up to 75 pounds.17 Careful, sequential examination of the patient and the radiograph is probably preferable to an arbitrary choice of weight. Once reduction has been achieved, all but 5 pounds of weight can be removed to maintain alignment.

Neurologic deterioration has been reported during or following the use of traction for reduction of these injuries. This has generated controversy. The principal issues are the possibility of disc herniation at the level of the dislocation and whether MRI should be obtained prior to attempts at closed reduction. There have been reports of patients who have undergone reduction of facet dislocations and then suffered neurologic deterioration. These patients were found to have a disc herniation.18,19 This has led to the argument that open reduction from a ventral approach that addresses the disc pathology at the same time might be a preferable strategy to closed reduction.20 Conversely, a significant percentage of patients with facet dislocations have disc herniations on prereduction21 or postreduction22 MRI scans. An evidence-based review of closed reduction of facet dislocations was undertaken by the American Association of Neurological Surgeons/Congress of Neurological Surgeons Joint Section on Spinal Disorders.23 The authors found that the literature on this subject consists of class III evidence. Hence, no standards or guidelines could be recommended. The reported case series that they reviewed involved more than 1200 patients. They found an overall success rate of traction achieving reduction of 80% and a permanent neurologic complication rate of 1%, with a 2% rate of transient neurologic deterioration. They found that the causes of deterioration were not limited to disc herniation. Such causes also included overdistraction, spinal cord edema, and a more rostral noncontiguous injury. They noted that the number of deteriorations due to disc herniation in awake patients undergoing closed reduction was extremely small. On the basis of the literature reviewed, the authors proposed a set of treatment recommendations at the level of options. They recommend early closed reduction in awake patients who do not have an additional rostral injury. For patients who cannot be examined during traction or whose injuries cannot be reduced with traction, they recommend obtaining an MRI, and if a disc herniation is found, consideration can be given to ventral decompression before reduction. They conclude that a prereduction MRI in the awake patient is of uncertain benefit. As these recommendations are options and, hence, are made on the basis of level III evidence, there is latitude for judgment based on the particular clinical situation. If a prereduction MRI demonstrates a significant disc herniation, an argument could be made that even if the patient is no worse following closed reduction, the spinal cord will not have been fully decompressed by reduction of the dislocation and a ventral discectomy and fusion would ultimately be needed to achieve complete decompression. Thus, a ventral decompression and open reduction can be considered as an initial treatment that achieves both restoration of alignment and stabilization at the same time.

Fleming B.C., Krag M.H., Huston D.R., et al. Pin loosening in the halo-vest orthosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1325-1331.

Graham N., Gross A., Goldsmith C. Mechanical traction for mechanical neck disorders: a systematic review. J Rehab Med. 2006;38:145-152.

Grant G.A., Mirza S.K., Chapman J.R., et al. Risk of early closed reduction in cervical spine subluxation injuries. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(Suppl 1):13-18.

Hadley M.N., Walters B.C., Grabb P.A., et al. Initial closed reduction of cervical spine fracture-dislocation injuries. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(Suppl 3):S44-S50.

Subach B.R., McLaughlin M.R., Albright A.L., et al. Current management of pediatric atlantoaxial rotator subluxation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23:2174-2179.

1. Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders. Scientific approach to the assessment and management of activity related spinal disorders: a monograph for clinicians. Report of the Quebec Task Force on Spinal Disorders. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1987;12:S1-S59.

2. . Hippocrates: On the articulations. Adams R., editor. The genuine works of Hippocrates:. translated from the Greek with a preliminary discourse and annotations. New York: William Wood. 1986;vol 2:75-156.

3. Taylor A.S. Fracture dislocation of the cervical spine. Ann Surg. 1929;90:321-341.

4. Crutchfield W.G. Skeletal traction for dislocation of the cervical spine: report of a case. South Surgeon. 1933;2:156-159.

5. Gardner W.J. The principle of spring loaded points for cervical traction. J Neurosurg. 1973;39:543-544.

6. Nickel V.L., Perry J., Garrett A., et al. The halo: a spinal skeletal traction fixation device. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1968;50:1400-1409.

7. Graham N., Gross A. Goldsmith C: Mechanical traction for mechanical neck disorders: a systematic review. J Rehab Med. 2006;38:145-152.

8. Subach B.R., McLaughlin M.R., Albright A.L., Pollack I.F. Current management of pediatric atlantoaxial rotator subluxation. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1998;23:2174-2179.

9. Garfin S.R., Botte M.J., Waters R.L., Nickel V.L. Complications in the use of the halo fixation device. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1986;68:320-325.

10. Fleming B.C., Krag M.H., Huston D.R., et al. Pin loosening in the halo-vest orthosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25:1325-1331.

11. Garfin S.R., Botte M.J., Triggs K.J., et al. Subdural abscess associated with halo-pin traction. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1988;70:1338-1340.

12. Beatson T.R. Fractures and dislocations of the cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1963;45:21-35.

13. Braakman R., Vinken P.J. Unilateral facet interlocking in the lower cervical spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1967;49:249-257.

14. Hadley M.N., Fitzpatrick B.C., Sonntag V.K.H., Browner C.M. Facet dislocation injuries of the cervical spine. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:661-666.

15. Lee A.S., MacLean J.C., Newton D.A. Rapid traction for reduction of cervical spine dislocations. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1994;76:352-356.

16. Star A.M., Jones A.A., Cotler J.M., et al. Immediate close reduction of cervical spine dislocations using traction. Spine. 1990;15:1068-1072.

17. Blumberg K.D., Catalano J.B., Cotler J.M., Balderston R.A. The pullout strength of titanium alloy MRI compatible and stainless steel incompatible Gardner-Wells tongs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1993;18:1895-1896.

18. Eismont F.J., Arena M.J., Green B.A. Extrusion of an intervertebral disc associated with traumatic subluxation or dislocation of cervical facets. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1991;73:1555-1560.

19. Robertson P.A., Ryan M.D. Neurological deterioration after reduction of cervical subluxation: mechanical compression by disc tissue. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1992;74:224-227.

20. Doran S.E., Papadopoulos S.M., Ducker T.B., Lillehei K.O. Magnetic resonance imaging documentation of coexistent traumatic locked facets of the cervical spine and disc herniation. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:341-345.

21. Rizzolo S.J., Piazza M.R., Cotler J.M., et al. Intervertebral disc injury complicating cervical spine trauma. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1991;16(Suppl 6):S187-S189.

22. Grant G.A., Mirza S.K., Chapman J.R., et al. Risk of early closed reduction in cervical spine subluxation injuries. J Neurosurg. 1999;90(Suppl 1):13-18.

23. Hadley M.N., Walters B.C., Grabb P.A., et al. Initial closed reduction of cervical spine fracture-dislocation injuries. Neurosurgery. 2002;50(Suppl 3):S44-S50.