53 Spinal Cord Tumors

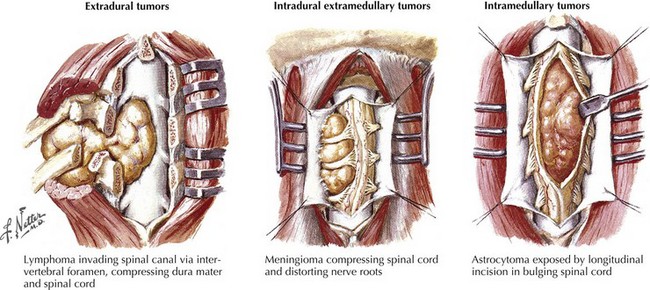

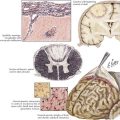

The most common spinal cord tumors are metastatic extradural lesions usually but not always occurring in patients with already identified malignancies, either cancers or lymphomas. Their presentation is often relatively acute, usually associated with focal back and/or radicular pain. On occasion, these lesions are the initial clinical manifestation of a heretofore unsuspected systemic malignancy. In contrast, primary intradural spinal cord tumors occur infrequently; typically their presentation is a relatively subtle one, ingravescent in temporal profile. Spinal cord and spinal column tumors are best classified within two categories: extradural, occurring outside of the dura, and intradural, contained within the dura mater (Table 53-1; Fig. 53-1).

Table 53-1 Classification of MRI Abnormalities*

| Extradural Extramedullary | Intradural Extramedullary | Intradural Intramedullary |

|---|---|---|

| Disc disease | Neurinoma | Syringomyelia |

| Metastatic carcinoma | Meningioma | Tumor |

| Lymphoma | Intracranial tumor seeding | Ependymoma |

| Sarcoma | Ependymoma | Glioma |

| Plasmacytoma | Medulloblastoma | Hemangioblastoma |

| Primary bone tumor | Glioma | Myelitis |

| Scar | Cauda equina lesions | Edema |

| Abscess | Scarring | Lipoma |

| Hemangioma | Hypertrophic neuropathy | Rare lesions |

| Rare lesions | Rare lesions | Abscess |

| Hemorrhage | Lymphoma | Hematoma |

| Neurilemmoma | Metastasis | Varix with AVM |

| Meningioma | Hemangioblastoma | Lymphoma |

| Chordoma | Lipoma | Neuroblastoma |

| Dermoid | Metastasis | |

| Epidermoid | ||

| Cyst | ||

| Clot |

* Dermoid or epidermoid, teratoma, lipoma, and cysts are often associated with spinal dysraphism. In this setting, many tumors are intradural, although they may involve all three areas.

Extradural Spinal Tumors

Clinical Vignette

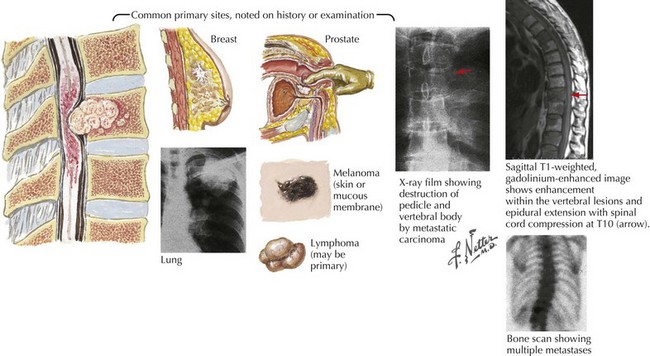

Spinal radiographs revealed destruction of the T9 vertebral body. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a soft tissue mass involving most of the T9 vertebral body, extending into the pedicle, with epidural extension of the tumor into the spinal canal leading to marked compression of the spinal cord. Immediate dexamethasone and subsequent radiation therapy was unsuccessful in reversing his clinical course. Chest radiograph (Fig. 53-2) demonstrated a left main stem bronchus tumor that on biopsy proved to be a primary small cell lung cancer.

Clinical Presentation

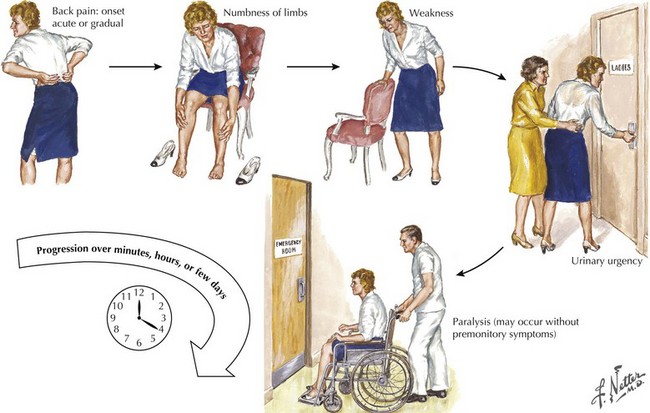

Severe focal vertebral pain is frequently the presenting symptom of a metastatic spinal cancer (Fig. 53-2). Unfortunately, back pain is such a ubiquitous complaint that the serious nature of a newly occurring pain is often not appreciated even when there is no history of recent trauma. Sometimes, it is difficult to distinguish pain of a metastatic spinal tumor from the much more common mechanical, degenerative, or osteoarthritic musculoskeletal lower back and/or nerve root disorders. However, pain of metastatic spinal cancer origin is often persistent, frequently unrelated to posture, and tends to increase at night. In contrast to more common mechanical back pain, this pain can be of more recent origin.

Typically, the course of extradural metastatic spinal tumors is more rapid than intradural tumors. It is not unusual for these lesions to have an almost precipitous onset, often producing rapidly evolving motor and sensory deficits within just a few hours to a day or so (Fig. 53-3). A prior diagnosis of either a cancer or a lymphoma will alert the astute clinician to the precise pathophysiologic nature of the spinal lesion. However, occasionally a spinal metastasis may be the initial presentation of a metastatic malignancy.

Diagnostic Approach

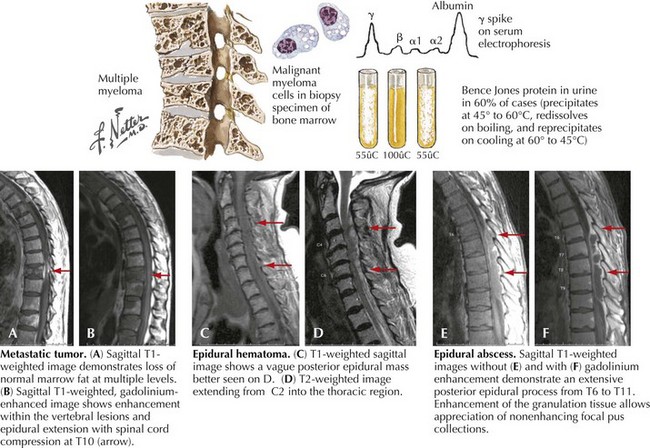

If a primary cancer has not been previously found, a histologic diagnosis becomes mandatory to confirm the nature of the lesion. In some instances, there is a primary bony malignancy such as multiple myeloma originating within the vertebrae per se (Fig. 53-4). Today percutaneous CT-guided needle biopsy is often the most useful procedure if no primary is immediately apparent such as occurred in this chapter’s opening vignette, where a routine chest radiograph led to a diagnostic lung biopsy. When there is no evidence of a primary lesion identified, an open surgical procedure, such as neurosurgical spinal cord decompression with a conjoint biopsy, is very important.

Treatment and Prognosis

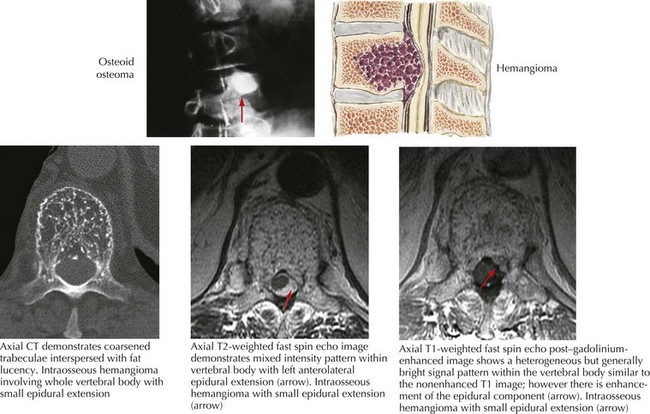

Very occasionally, one finds a few types of primary benign bony vertebral tumors. Although histologically these are not malignant as are most extradural tumors, these lesions may reach a critical mass, causing vertebral collapse and spinal cord compression (Fig. 53-5). Usually these benign tumors have a less aggressive clinical course; however, once they reach a critical mass, they may portend serious threat to spinal cord function. Uncommonly, surgical decompression is indicated.

Clinical Vignette

Continued observation was therefore important, as were patient instructions to call with any new symptomatology and return for follow-up within a few months. On this occasion, subsequent neurologic examination demonstrated a subtle sensory cord level and contralateral corticospinal dysfunction, typical of a classic Brown–Sequard syndrome indicating a specific level of spinal cord dysfunction (see Chapter 44). Focused spinal MRI at a higher level led to the diagnosis of this treatable lesion.

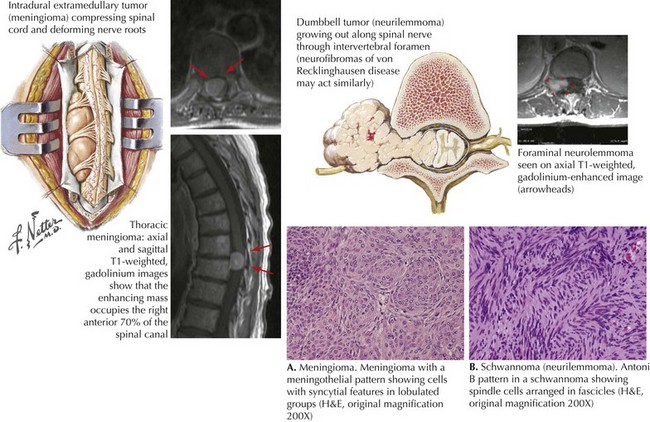

Intradural extramedullary tumors are most commonly meningiomas (Fig. 53-6A) arising from within the dura per se, or are nerve sheath tumors. The latter are classified into two main groups, schwannomas, about 65% (Fig. 53-6B), and neurofibromas. Both often have a similar gross appearance and require microscopic analysis for differentiation. Neurofibromas have less dense cellular structure (Antoni B pattern) and often contain nerve elements. Usually benign, these lesions occur as a solitary finding or as multiple nodules throughout the body. Type I neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen disease) is a familial condition with two or more neurofibromas, associated neurocutaneous findings such as café-au-lait spots, and axillary freckling. Nerve sheath tumors such as schwannomas typically develop in middle-aged women. These lesions are benign, slow-growing tumors that gradually lead to significant clinical symptomatology especially when these originate near the spinal cord. Type I neurofibromatosis (von Recklinghausen disease) is an autosomal dominant disorder often associated with optic gliomas, and Lisch nodules of the iris, along with certain skeletal abnormalities. Type II neurofibromatosis is most frequently associated with bilateral hearing loss due to neurofibromas of the eighth cranial nerve and are not associated with spinal cord compression (see Chapter 52). Schwannomas have a dense pattern on microscopic analysis and may be found at the level of the nerve root.

Intradural Intra-axial Tumors

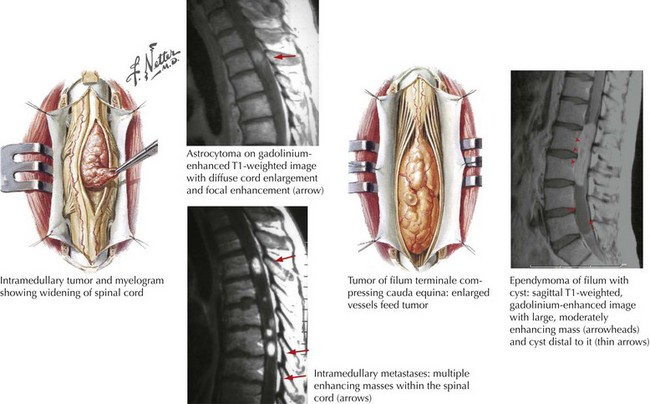

Tumors that originate and grow within the substance of the spinal cord are designated as intra-axial lesions, that is, “intradural, intramedullary” neoplasms (Fig. 53-7). These account for ~15% of all primary intradural tumors occurring in both children and adults.

Clinical Vignette

Clinical Presentation

Intramedullary tumors often present with progressive painless neurologic decline over several weeks. The above vignette demonstrated a classic Brown–Sequard syndrome characterized by unilateral hemimotor weakness, diminished position and vibratory sensation ipsilateral to the lesion, and loss of pain and temperature in the contralateral lower extremity. This classic presentation is typically seen in tumors predominantly occupying one side of the spinal cord. A “pure” Brown–Sequard syndrome is rare, as most patients with intradural intramedullary lesions have a mixed clinical presentation affecting both sides of the spinal cord (Fig. 53-7).

Albanese V, Platania N. Spinal intradural extramedullary tumors. Personal experience. J Neurosurg Sci. 2002;46(1):18-24.

Avanzo M, Romanelli P. Spinal radiosurgery: technology and clinical outcomes. Neurosurg Rev. 2009 Jan;32(1):1-13.

Bowers DC, Weprin BE. Intramedullary spinal cord tumors. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2003;5(3):207-212.

Cole JS, Patchell RA. Metastatic epidural spinal cord compression. Lancet Neurol. 2008 May;7(5):459-466. Review

Conti P, Pansini G, Mouchaty H, et al. Spinal neurinomas: retrospective analysis and long-term outcome of 179 consecutively operated cases and review of the literature. Surg Neurol. 2004;61(1):34-44.

George R, Jeba J, Ramkumar G, et al. Interventions for the treatment of metastatic extradural spinal cord compression in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008 Oct 8;(4):CD006716.

Gibson CJ, Parry NM, Jakowski RM, et al. Anaplastic astrocytoma in the spinal cord of an African pygmy hedgehog (Atelerix albiventris). Vet Pathol. 2008 Nov;45(6):934-938.

Minehan KJ, Brown PD, Scheithauer BW, et al. Prognosis and treatment of spinal cord astrocytoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008 Aug 5. This consecutive series of patients with spinal cord astrocytoma were treated at Mayo Clinic Rochester between 1962 and 2005. RESULTS: A total of 136 consecutive patients were identified. Of these 136 patients, 69 had pilocytic and 67 had infiltrative astrocytoma. The median follow-up for living patients was 8.2 years (range, 0.08-37.6), and the median survival for deceased patients was 1.15 years (range, 0.01-39.9). The extent of surgery included incisional biopsy only (59%), subtotal resection (25%), and gross total resection (16%). The results of our study have shown that histologic type is the most important prognostic variable affecting the outcome of spinal cord astrocytomas. Surgical resection was associated with shorter survival and thus remains an unproven treatment. Postoperative radiotherapy significantly improved survival for patients with infiltrative astrocytomas but not for those with pilocytic tumors

White BD, Stirling AJ, Paterson E, et al. Diagnosis and management of patients at risk of or with metastatic spinal cord compression: summary of NICE guidance. Guideline Development Group. BMJ. 2008 Nov 27;337:a2538.