187 Soft Tissue Injury

• Retained foreign bodies (FBs) can cause pain, infection, delayed healing, nerve and tendon injury, masses, and functional impairment.

• Specific injuries, such as those caused by broken glass or surfaces with gravel and stepping on objects, are particularly prone to retained FBs.

• Wounds should be explored for FBs with adequate anesthesia and lighting in a bloodless field.

• Plain radiographs are useful in evaluating for radiopaque FBs and should be ordered commonly.

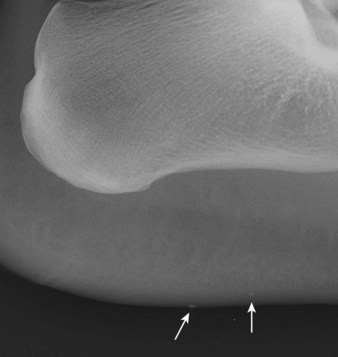

• Plain films may miss nonradiopaque FBs such as wood, plastic, and vegetative matter. They may also miss radiopaque FBs that are tiny, obscured by bone, or in areas that are difficult to obtain quality images, such as the face or sole of the foot.

• Ultrasound scans and portable fluoroscopic studies may aid in localization and removal of FBs. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are rarely indicated.

• Neither exploration nor imaging alone can rule out an FB. The two should be used in combination in most instances. No wound is too small or superficial to harbor an FB.

• Careful discharge instructions are crucial and can minimize the morbidity and medicolegal risk associated with retained FBs. Patients should be informed that it is impossible to detect all FBs, be told what to expect in the event of a missed FB, and be given appropriate referral should these circumstances arise.

• Direct exploration of wounds plus visualization of tendons placed through a full range of motion is necessary for proper evaluation of tendon injuries.

• A detailed neurovascular examination is required to identify possible nerve lacerations.

• Most tendon and nerve lacerations can be repaired on an outpatient basis. Ensuring appropriate and timely follow-up is important.

Retained Foreign Bodies

Epidemiology

Open wounds are frequent reasons for emergency department (ED) visits. The true incidence of foreign bodies (FBs) in wounds is unknown, but with more than 5 million estimated lacerations repaired in EDs in 2007,1 wound FBs surely occur in such a significant number that all emergency physicians (EPs) will encounter them. Wound FBs are frequently missed on initial evaluation. Seventy-five of 200 FBs encountered in a hand clinic were missed by the initial physician.2 Furthermore, missed FBs pose high medicolegal risk for EPs, with one report listing it to be among the top three causes of litigation after wound care.3

Most wound FBs are wood, glass, or metal. The upper extremity is the most common location (58%), followed by the lower extremity (36%). The head and neck (4%) and the trunk (1%) are far less common. Most cases will be seen on the day of injury (75%), but some (8.7%) will initially be evaluated weeks, months, or years later.4

Pathophysiology

A retained FB can lay harmlessly dormant for a long period and then can react with surrounding tissue. When a tissue reaction occurs, several sequelae are possible. An infection may occur. The patient’s body may dissolve, extrude, or encapsulate the FB and form a granuloma, and subsequent rupture of the granuloma from minor trauma can cause delayed infection. The extent of tissue reaction depends primarily on the chemical composition of the material. Inert material causes less tissue inflammation, whereas reactive material can cause intense tissue reactions (Box 187.1) and rarely even allergic reactions. Even when an FB does not cause a tissue reaction, it can have other effects. The FB may cause local compression on neighboring structures such as nerves, tendons, joints, or vessels, thereby causing pain or structural damage. Local migration or, more rarely, distant embolization can also occur.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

The classic example of a wound FB is a patient who sees or knows that foreign material is present in a wound, such as a splinter, glass in the sole of the foot that the patient cannot remove, or an obviously soiled wound. Alternatively, it is also common for a patient to have a wound and not to know that foreign material is present. The chief complaint of such patients is simply that they have a wound. Certain mechanisms are highly suggestive of wound FBs (Box 187.2).5–8 Some unique wound FBs include shrapnel, fishhooks, bullets and BBs, cactus spines, and marine material (Table 187.1). Some patients may exhibit sequelae of a retained FB from the near or distant past, such as a mass, persistent pain, infection, functional impairment as a result of nerve or tendon injury, arthritis, vascular injury, or embolization.

Box 187.2 Scenarios Suggestive of Foreign Bodies in Wounds

History of punching through a window

Motor vehicle collision wounds from glass

Wounds on the sole of the foot

Objects that fragment while in one’s hand

Pain at a site of intravenous drug use

Foot laceration while walking in a stream

Wound infection, especially if persistent

| TYPE OF FOREIGN BODY | TIPS AND COMMENTS |

|---|---|

| Fishhooks | Anesthetize the area, advance the tip of the fishhook through the skin, cut the barb, and withdraw the hook. |

| Splinters | Do not pull long splinters out because they tend to fragment. Instead, excise along the long axis or elliptically. |

| Needle tips | Removal may require excision of a block of tissue. |

| Shrapnel | When extensive, emergency department removal of all shrapnel may not be feasible or indicated. Remove as much as reasonably possible, with a focus on dangerous locations, and refer the patient for further treatment. |

| Bullets, BBs | These items are often left in situ, but objects larger than 4.5 mm in diameter tend to track skin and clothing into wounds, so visualize, irrigate, and leave open when possible. Remove these objects only if they are easily accessible or in the pleura (risk for lead poisoning). |

| Cactus spines | Use fine-tipped forceps or glue to remove them. |

| Marine envenomations | Treatment (hot water immersion, vinegar, shaving) depends on the type of spine or nematocyst. |

| Traumatic tattooing | Sources include pencils and blacktop. Débride with a scrub brush. Management is difficult. Consider referral to dermatology or plastic surgery for dermabrasion or laser treatment. |

Neither the presence nor the absence of FB sensation on the part of the patient can confidently rule in or exclude an FB. In a series of 164 wounds caused by glass, 41% that contained glass caused an FB sensation, with a positive predictive value of 31% and a negative predictive value of 89%.5

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

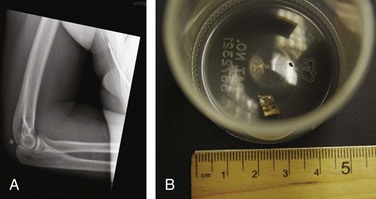

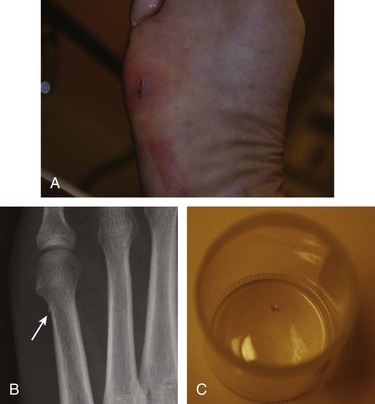

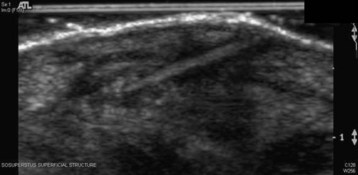

No wound is too small or superficial to harbor an FB, and thus the possibility of an FB must be considered for all wounds. Most wound FBs are initially diagnosed by physical examination (78%), but many are diagnosed primarily by imaging studies (22%).4 Exploration alone is insufficient to rule out an FB,5,9,10 even when the entire wound is thought to be visualized. Therefore, imaging should be used liberally. Selection of the proper imaging modalities requires knowledge of the radiographic properties of the material (Box 187.3 and Figs. 187.1 through 187.3). Even when a suspected FB is not radiopaque, plain film radiographs with an underpenetrated soft tissue technique could be considered because other useful soft tissue or bony findings and reactions may be present. Furthermore, failure to order radiographs has been associated with unsuccessful legal defense in cases of retained FBs.11 Ultrasound scanning is particularly useful for nonradiopaque FBs (Fig. 187.4).7 Low-power portable fluoroscopy, when available, is useful to aid in removal of radiopaque FBs. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are rarely indicated. However, computed tomography may be useful for ocular or periorbital FBs (Table 187.2).12,13

| IMAGING MODALITY | POSITIVE FEATURES | NEGATIVE FEATURES |

|---|---|---|

| Radiography |

* Courter BJ. Radiographic screening for glass foreign bodies: what does a “negative” foreign body series really mean? Ann Emerg Med 1990;19:997-1000.

† Horton LK, Jacobson JA, Powell A, et al. Sonography and radiography of soft-tissue foreign bodies. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;176:1155-9.

After an FB is diagnosed, the next step is to decide whether to attempt removal or to leave the FB in place. Not all FBs require removal. If an FB is deep, small, inert, away from vital structures, and asymptomatic, attempts at removal may be more destructive than helpful (Box 187.4). Irrigation is an important intervention that not only cleans the wound but also often removes tiny FBs and particulate matter that would otherwise be difficult to localize.

Box 187.4

Indications for Removal of Foreign Bodies

Functional impairment, restriction of motion

Reactive material: wood, thorn, other vegetative material, clothing

Toxicity: venomous spines, lead poisoning from bullets

Impingement of nerve, tendon, vessel

Intraarticular or periarticular location

High potential to migrate toward anatomic structures or to embolize

From Lammers RL, Magill T. Detection and management of foreign bodies in soft tissue. Emerg Med Clin North Am 1992;10:767-81.

Tips and Tricks

Foreign Body

Exploration

Equipment: loupes, fine-tipped forceps helpful

Possible need to extend the incision

Incision perpendicular to the long axis of long, thin foreign bodies (splinters, needles) for localization

Bloodless field and adequate anesthesia required

Listening for grating sounds of the foreign body against the probe

Treatment (see the “Tips and Tricks” box)

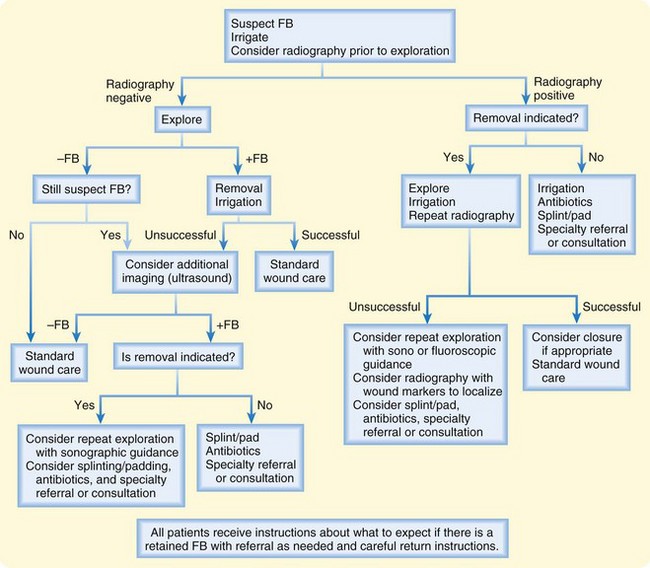

Wounds that are contaminated or may still contain FBs should be left open or packed. Antibiotics should probably be prescribed for these patients. EPs should be sure to pad or splint areas with retained FBs before patients are discharged. If all FBs have been removed and the wound has been thoroughly cleansed, closure may be appropriate. An algorithm for an approach to FBs is presented in Figure 187.5.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Admission is seldom indicated. Admission scenarios may include severe infections and FBs that are going to be removed in the operating room. Documentation and patient education are important aspects of all wound cases. (See the “Documentation”, “Patient Teaching Tips”, “Red Flags”, and “Priority Actions” boxes.)

![]() Documentation

Documentation

Soft Tissue Injury

History

Detailed mechanism, hand dominance, timing, type of material, whether the object broke on impact or was already broken, whether the wound was soiled, whether anything was pulled out of the wound, FB sensation, paresthesia, weakness, tetanus immunization status, medical conditions that may impair healing or compromise immune function, intravenous drug use, and persistent pain, infection, or drainage

Physical Examination

Position of the hand at rest, detailed neurovascular examination including two-point discrimination, ability to achieve active range of motion and the presence of pain with passive motion, wound size and depth, tenderness, visible contaminants, infection, tattooing, discoloration, signs of infection, and masses

![]() Patient Teaching Tips

Patient Teaching Tips

Inform patients with wounds of the remote possibility of a missed foreign body because there is no way to truly guarantee that all foreign material has been identified and removed.

After the first couple days, a normal wound should show consistently gradual improvement in pain, swelling, and discoloration.

Inform patients that a retained foreign body may result in persistent pain, loss or impairment of function, a mass, infection, or injury to a nerve, tendon, vessel, or joint. These complications may develop even months or years later.

If any of the foregoing situations develop, the patient should know to return to the emergency department or should have received specialty referral.

Warn the patient to return for signs of infection, including redness, discharge, pain, and swelling.

Warn patients who have documented partial tendon lacerations, depending on the degree of laceration and findings on subsequent examination, that the referring physician may or may not repair the injury.

Inform all patients of the possibility of tendon or nerve lacerations not visualized on examination.

If a nerve or tendon laceration has been documented, ensure that the patient understands the importance of timely follow-up.

Tendon and Nerve Lacerations

Epidemiology

Lacerations are one of the most common chief complaints of patients seen in the ED. It is estimated that a total of 6,400,000 open wounds were treated in EDs in the United States in 2004, thereby making open wounds anywhere on the body the third leading primary diagnosis group. Approximately one third of all open wounds are located on the upper extremity (specifically the fingers, hand, or wrist).14 An improperly functioning or insensate digit as a result of tendon or nerve injury can lead to markedly impaired function and significant subsequent morbidity. Wound claims, particularly of the hand, are a leading cause of litigation.3 Although lacerations about the foot and ankle are also relatively common, given the importance and prevalence of hand injuries, this part of the chapter focuses primarily on tendon and nerve lacerations of the hand.

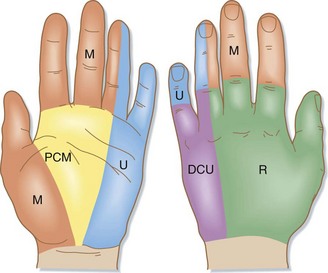

Pathophysiology

The nerve supply to the hand is provided by the radial, ulnar, and median nerves. The radial nerve is purely sensory in the hand (motor function of the radial nerve includes wrist extension). The median and ulnar nerves provide the entire motor function of the hand and some sensory function as well (Fig. 187.6). Each digit has two neurovascular bundles located near the palmar aspect of the finger, one on the radial side and the other on the ulnar side.

Fig. 187.6 Cutaneous nerve supply in the hand.

(Redrawn from Lyn E, Antosia RE. Hand. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, eds. Rosen’s emergency medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2006. p. 576-621.)

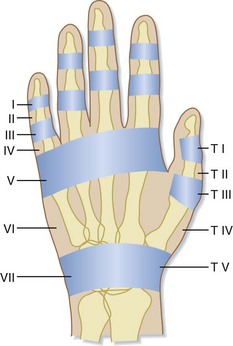

The extensor tendons are located on the dorsal surface of the forearm, wrist, and hand. Nine extensor tendons pass under the extensor retinaculum. The extensor tendons join to become the extensor expansion and then separate into six fibroosseous compartments. In each digit, the extensor expansion then divides into a central slip attaching to the middle phalanx and two lateral bands joining with the tendons of the lumbricals and then continuing on to attach to the base of each distal phalanx. See Figure 187.7 for extensor tendon zone classification.

Fig. 187.7 Zone classification of extensor tendon injuries.

(Redrawn from Lyn E, Antosia RE. Hand. In: Marx JA, Hockberger RS, Walls RM, eds. Rosen’s emergency medicine. 6th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2006. p. 576-621.)

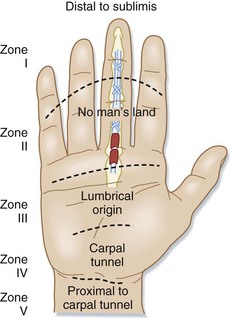

The superficial location of the tendons and nerves of the hand combined with the lack of overlying subcutaneous tissue predisposes these structures to injury. Injuries to the tendons have been grouped into anatomic zones for easy understanding and classification. The most widely accepted classification system is that of Verdan. This system uses eight zones, from zone I at the distal interphalangeal joint level to zone VIII at the distal forearm level. This system has been modified to five zones for the flexor tendons (Fig. 187.8).15 Although the Verdan system is no longer used to determine treatment options, knowledge of the zones is useful for prognosis.

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

Any patient with a laceration about the hand or wrist may have sustained a tendon or nerve laceration regardless of how superficial the wound may appear. In a study of 226 patients with upper extremity lacerations that were less than 2 cm in length, 59% were found to have at least one injury to a deep structure.16 Depending on the degree of injury, the patient may have no obvious injury other than a laceration through the skin.

The normal resting position of the hand—flexed fingers, with the little finger having the greatest degree of flexion and the index finger the least—may be altered in patients with a complete tendon laceration (Fig. 187.9). Flexor tendon disruption is indicated when the injured finger lies in complete extension while the others are in slight flexion. When the patient has an extensor tendon injury, the affected digit is held in full flexion while the others are held in slight extension or the normal position of function. Partial lacerations may not be evident based on the position of the finger. Limited or painful movement, especially if more severe than would be expected with the laceration, suggests partial tendon involvement.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

A systematic examination of the hand and wrist includes assessment of active and passive range of motion of the wrist and digits. To check specifically for extensor tendon injuries, the patient should actively extend each finger and then extend each finger against resistance. In evaluating the flexor tendons, the superficialis and profundus tendons should be tested independently, with the patient actively flexing individual proximal and distal interphalangeal joints (Fig. 187.10). Examiners should be sure to check tendon motion against resistance because patients with partial tendon lacerations may have normal range of motion.

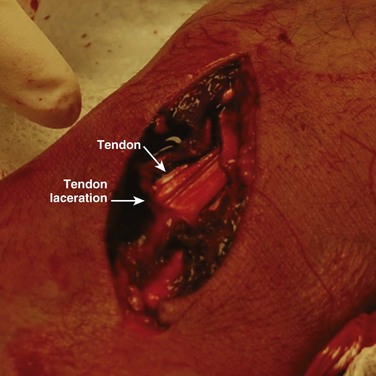

The next step is exploration of the wound (Fig. 187.11), which is best done with the EP seated comfortably with optimal anesthesia, hemostasis, lighting, and equipment. Adequate anesthesia is crucial. Failure to provide adequate exposure of deeper wound structures because of the patient’s discomfort often leads to missed injuries. The wound should be explored in a bloodless field. A tourniquet may be required if direct pressure is insufficient to achieve such a field. The wound should be visualized completely and with full range of motion of the involved digit.

Additional studies or imaging techniques are indicated to evaluate for FBs, fractures, and avulsions. They are not useful in evaluating tendon or nerve lacerations. Ultrasonography may be a viable diagnostic tool in evaluating tendon injuries, although at this time it has not been studied in the ED.17

Treatment

All motor branches of the ulnar and median nerve should be repaired. Both consultation in the ED and referral the following day after discussion with the referring physician are appropriate (Box 187.5). Digital nerve injuries proximal to the distal interphalangeal crease on the radial aspect of the index and middle fingers, the ulnar side of the little finger, and both sides of the thumb should be repaired. The timing of repair for simple, clean nerve injuries is somewhat controversial; some data show better results with repair in 6 to 12 hours, whereas other data show acceptable results with delayed repair.18 Satisfactory return of function can occur after nerve repair or a graft performed within 3 months of injury.19 Any patient with a suspected nerve injury should be referred to a specialist for evaluation and possible repair.

Patients with tendon lacerations (partial or complete) require early referral to a surgeon. Most surgeons recommend repairing complete lacerations primarily within 12 to 24 hours after the injury. However, data on delayed primary (<10 days) or early secondary (2 to 4 weeks) repair show little difference in outcomes when compared with the traditional immediate repair.20 Repair of partial tendon lacerations is still controversial, and most hand surgeons now repair only lacerations that involve more than 50% of the tendon surface. Regardless of whether the laceration is full or partial, primary coverage of the injured tendon by skin suturing after wound irrigation protects the tendon and retards infection, but it should be undertaken only after consultation with the specialist who will perform the definitive repair.

Follow-Up, Next Steps in Care, and Patient Education

Most patients with tendon and nerve lacerations can be discharged home safely from the ED. Educating the patient regarding expectations and the importance of follow-up is of utmost importance. All patients with documented or suspected lacerations of a tendon or nerve require evaluation by the appropriate surgeon. ED consultation and early referral following discussion with a specialist are both appropriate courses of action. If severe infection or important structural damage is present, ED consultation may be more prudent than outpatient follow-up. The area should be splinted appropriately and antibiotics prescribed if indicated. Flexor injuries should be splinted with the wrist in 30 degrees of flexion, the metacarpophalangeal joints flexed 70 degrees, and the interphalangeal joints flexed 10 to 15 degrees. A metal protective splint is recommended for patients who are going to return to work. All but very minor hand wounds are best followed up within 48 hours for removal of the dressing and inspection of the wound for signs of infection. (See Box 187.6 for complications.)

Anderson MA, Newmeyer WL, Kilgore ES. Diagnosis and treatment of retained foreign bodies in the hand. Am J Surg. 1982;144:63–67.

Avner JR, Baker MD. Lacerations involving glass: the role of routine roentgenograms. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:600–602.

Courter BJ. Radiographic screening for glass foreign bodies: what does a “negative” foreign body series really mean? Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:997–1000.

Lee DH, Robbin ML, Galliott R, et al. Ultrasound evaluation of flexor tendon lacerations. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2000;25:236–241.

Levine MR, Gorman SM, Young CF, et al. Clinical characteristics and management of wound foreign bodies in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:918–922.

Steele MT, Tran LV, Watson WA. Retained glass foreign bodies in wounds: predictive value of wound characteristics, patient perception, and wound exploration. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16:627–630.

Tuncali D, Yavuz N, Terzioglu A, et al. The rate of upper-extremity deep-structure injuries through small penetrating lacerations. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:146–148.

1 Niska R, Bhuiya F, Xu J. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2007 emergency department summary. Natl Health Stat Rep. 2010;26:1–32.

2 Anderson MA, Newmeyer WL, Kilgore ES. Diagnosis and treatment of retained foreign bodies in the hand. Am J Surg. 1982;144:63–67.

3 Karcz A, Korn R, Burke MC, et al. Malpractice claims against emergency physicians in Massachusetts: 1975-1993. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:341–345.

4 Levine MR, Gorman SM, Young CF, et al. Clinical characteristics and management of wound foreign bodies in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2008;26:918–922.

5 Steele MT, Tran LV, Watson WA. Retained glass foreign bodies in wounds: predictive value of wound characteristics, patient perception, and wound exploration. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16:627–630.

6 Montano JB, Steele MT, Watson WA. Foreign body retention in glass-caused wounds. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21:1360–1363.

7 Lammers RL, Magill T. Detection and management of foreign bodies in soft tissue. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1992;10:767–781.

8 Lammers RL. Soft tissue foreign bodies. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;17:1336–1347.

9 Gron P, Andersen K, Vraa A. Detection of glass foreign bodies by radiography. Injury. 1986;17:404–406.

10 Avner JR, Baker MD. Lacerations involving glass: the role of routine roentgenograms. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146:600–602.

11 Kaiser CW, Slowick T, Spurling KP, et al. Retained foreign bodies. J Trauma. 1997;43:107–111.

12 Courter BJ. Radiographic screening for glass foreign bodies: what does a “negative” foreign body series really mean? Ann Emerg Med. 1990;19:997–1000.

13 Horton LK, Jacobson JA, Powell A, et al. Sonography and radiography of soft-tissue foreign bodies. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;176:1155–1159.

14 McCraig LF, Burt CW. National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2004 Emergency Department Summary. Advance data from Vital and Health Statistics, no. 372. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 2006.

15 Steinberg DR. Flexor tendon lacerations in the hand. Univ Pa Orthop J. 1997;10:5–11.

16 Tuncali D, Yavuz N, Terzioglu A, et al. The rate of upper-extremity deep-structure injuries through small penetrating lacerations. Ann Plast Surg. 2005;55:146–148.

17 Lee DH, Robbin ML, Galliott R, et al. Ultrasound evaluation of flexor tendon lacerations. J Hand Surg [Am]. 2000;25:236–241.

18 Muller H, Grubel G. Long term results of peripheral nerve sutures: a comparison of micro-macrosurgical technique. Adv Neurosurg. 1981;9:381–387.

19 Kotwal PP, Gupta V. Neglected tendon and nerve injuries of the hand. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2005;43:66–71.

20 Stone JF, Davidson JS. The role of antibiotics and timing of repair in flexor tendon injuries of the hand. Ann Plast Surg. 1998;40:7–13.