35

Small babies

Introduction

Babies have a wide range of birth weights. While those born prematurely are more likely to be of low birth weight, the focus of this chapter is on fetuses and neonates who appear to be, or are, small for their gestational age (SGA). These babies may simply be small, in other words they are normal babies who just happen to be at the smaller end of a normal range (constitutionally or genetically small), or are small for a pathological reason. These latter fetuses are referred to as being affected by fetal growth restriction (FGR, previously called intrauterine growth restriction or IUGR).

The key issues are how to screen a low-risk population in order to identify these small fetuses and, once identified, how best to identify those that are risk of developing problems in utero or in labour.

Accuracy of dating

It is not possible to reliably diagnose SGA or FGR without accurate knowledge of gestation. Menstrual dating has significant inherent inaccuracies. The dates may be inaccurately recalled, the cycle may be irregular and bleeding in early pregnancy may be mistaken for menses. Gestation is most accurately determined by an ultrasound scan undertaken before 20 weeks’ gestation, as it is reasonable to assume that all fetuses are of similar size, up until this point. The natural variation in size after this stage makes accurate dating very difficult. The most reliable measurements are based on the crown–rump length between the 8th and 14th weeks, and the head circumference between the 15th and 20th weeks.

The estimated date of delivery is taken as 40 weeks after the date of the start of the last menstrual period (LMP), providing the cycle length is 28 days. A correction may be made for those with regular longer or shorter cycles; for example, if the cycle is 35 days long, then 7 days should be added to the date of the LMP. Abdominal palpation is an inaccurate way of establishing gestational age, as is the date that fetal movements were first noted. The rest of this chapter will assume that gestational age is reliably established.

Small-for-gestational-age (SGA)

Small-for-gestational-age describes the fetus or baby whose birth weight or estimated fetal weight is below a specified centile for its gestation at birth. The chosen centile may be the 10th, 5th or 3rd, depending on different policies, and this choice reflects a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. If the 10th centile is chosen, it will correctly identify most fetuses liable to be at risk due to their small size but will also include many other fetuses who are not at risk. If the 3rd centile is chosen, then specificity will be good, in other words a greater proportion of identified babies will be at risk, but more ‘at-risk’ fetuses might be missed. The most commonly used threshold is the 10th centile.

Fetal growth restriction (FGR)

The term fetal growth restriction indicates ‘a fetus which fails to reach its genetic growth potential’. FGR presents as a fetus whose growth on serial ultrasound scanning falls below a certain threshold. This threshold is poorly defined and is often implied as the crossing of centiles on a chart of fetal biometry (see later).

Babies with FGR appear thin, as measured by the ponderal index (the ratio of body weight to length) and their skin-fold thickness, a measure of subcutaneous fat, is reduced. There is clearly an overlap in the categorization of small and/or growth-restricted fetuses; a proportion of SGA fetuses will be growth restricted but the majority will be constitutionally small, i.e. genetically determined to be small. Some growth-restricted fetuses will not be SGA, i.e. their growth is failing but they do not have a size below the 10th centile.

Aetiology

Fetal growth is determined by the baby’s intrinsic genetic potential, which is then modified by various fetal, maternal and placental factors (Box 35.1).

Fetal factors affecting fetal growth

The genetic make-up of the fetus is the main determinant of its growth and is related to a number of factors, including ethnicity. Asian mothers, for example, have smaller babies than their European counterparts.

This intrinsic genetic drive to grow is more related to the maternal genome than the genome of the father, and involves ‘genomic imprinting’. It is well recognized that while large women often have correspondingly large babies, the correlation between large men and the size of their baby is poor.

Many developmentally abnormal fetuses are small, presumably as a result of a decreased intrinsic drive. This is particularly seen with chromosomal abnormalities, for instance trisomies 18, 13, 21 and triploidy. Small babies are also found in association with structural abnormalities of all the major organ systems as well as with fetal infection. These infections include toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus and rubella, but worldwide, the main association is with malaria.

Maternal factors affecting fetal growth

Small variations in diet do not have a measurable effect on fetal growth, but extreme starvation does cause significant growth impairment. This was observed in the Dutch winter famine of 1944 and during the Siege of Leningrad from 1941 to 1944. There is no evidence, however, that food supplementation above a normal diet can improve growth in utero.

Oxygen supply is important. Babies born at high altitude are small, presumably as a result of the decreased oxygen content found in the rarefied atmosphere. This is also true of babies born to mothers with chronic hypoxia secondary to congenital heart disease. The fetus is able to partly compensate through placental hypertrophy, but this compensation is incomplete.

Drugs such as tobacco, heroin, cocaine and alcohol may decrease fetal growth. It has been estimated that smoking, for example, will decrease neonatal weight by an average of approximately 150 g. Maternal chronic disease also has an adverse effect on fetal growth, particularly if there is renal impairment.

Placental factors affecting fetal growth

Adequate placental function depends on adequate trophoblastic invasion. In the first trimester, trophoblast cells invade the maternal spiral arteries in the decidua. In the second trimester, a secondary wave of trophoblast extends this invasion along the spiral arteries and into the myometrium. This results in the conversion of thick-walled muscular vessels with a relatively high vascular resistance to flaccid thin-walled vessels with a low resistance to flow. In certain conditions, such as pre-eclampsia, it would appear that there has been failure of this secondary trophoblastic invasion, the consequences being subsequent placental ischaemia, atheromatous changes and secondary placental insufficiency. Why this failure should occur is unclear, but may be related to the immunological interface between the fetal and maternal cells. In pre-eclampsia, there may be additional impaired placental flow from vasoconstriction. Local placental blood flow is under the control of prostacyclin and thromboxane A2, with thromboxane causing vasoconstriction and prostacyclin vasodilatation. There is a relative deficiency of prostacyclin in pre-eclampsia and an increase in the production of thromboxane A2, the net result being placental vessel vasoconstriction.

The overall effect of uteroplacental insufficiency, whatever the cause, is a decrease in the nutrient supply to the fetus. It is not surprising therefore that these fetuses are often found to be hypoxic, hypoglycaemic and sometimes acidotic. To compensate for this hypoxia, the fetus increases erythropoiesis in order to increase its oxygen-carrying capacity, and redistributes blood away from the peripheral circulation, gut and liver towards the brain, heart and adrenal glands.

The result is a baby with normal growth in length and brain development, but who is thin and has little or no subcutaneous fat. Glycogen stores are minimal. As these babies have relatively large heads compared with their bodies, their growth has previously been described as ‘asymmetrical’, although the terms ‘symmetrical’ and ‘asymmetrical’ are no longer used to describe patterns of fetal growth or neonatal nutritional status.

Screening and diagnosis

A number of risk factors for delivery of an SGA baby have been identified. Some of these are identifiable at the first visit, whereas others only feature during the course of the pregnancy (Box 35.2). The presence of such a risk factor justifies undertaking serial ultrasound fetal biometry from 26–28 weeks onwards in order to diagnose poor fetal growth. Often, however, small babies are identified following routine clinical examination.

Clinical examination

Estimation of fetal weight from clinical examination is unreliable. The fundus reaches the umbilicus by around 20–24 weeks and the xiphisternum by approximately 36 weeks. The height of the uterine fundus should be measured with a tape measure at each antenatal clinic visit from 26 weeks onwards; the height of the uterus, measured from the pubic symphysis is approximately equal to the gestation in weeks. Symphysis–fundal height (SFH) charts facilitate the interpretation of these measurements. An SFH less than the 10th centile, or serial SFH measurements suggestive of poor growth is an indication for ultrasound fetal biometry.

Ultrasound examination

Ultrasound is used to establish or refute the diagnosis of fetal SGA or FGR. Certain diagnosis of SGA or FGR can only be made with certainty postnatally, but this is of little value to the obstetrician and midwife in planning antenatal care/surveillance. Measurements can be made of the fetal head (circumference or biparietal diameter), the abdominal circumference and the femur length, and various equations can be used to estimate fetal weight. For practical purposes, it is reasonable to consider the abdominal circumference alone, as measurements below the 10th centile have an approximately 80% sensitivity in the prediction of SGA neonates in high-risk pregnancies. There is no evidence that routine ultrasound screening is of value in low-risk women.

SGA or FGR?

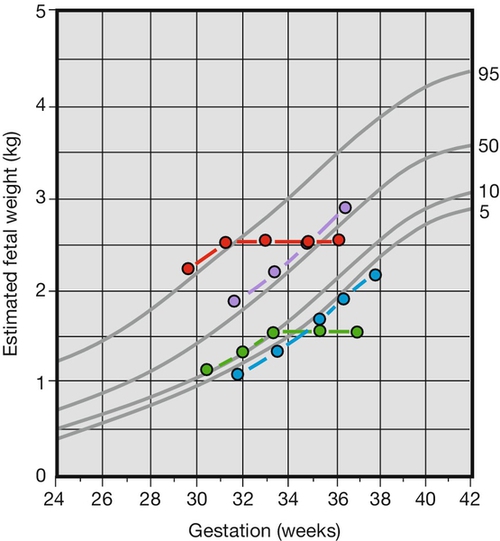

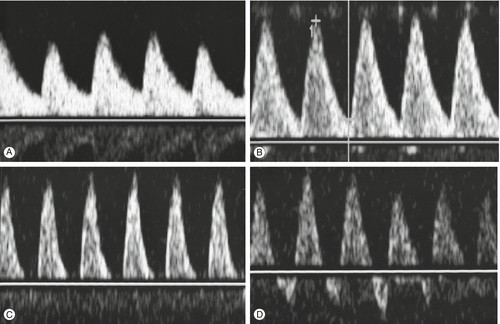

This is a key question and one which it is not always possible to answer. Those fetuses less than the 10th centile include those who are simply constitutionally small (perhaps around 70%) and those who have FGR. The increased risks of stillbirth, birth hypoxia, neonatal complications and impaired neurodevelopment are principally in the FGR group, and it would be of great value to be able to reliably differentiate between the two groups. The diagnosis of SGA is straightforward, but the diagnosis of FGR less so. Current clinical practice is to plot two or more fetal measurements on a chart of estimated fetal weight (or abdominal circumference) against gestational age. Examples of such plots in four fetuses are presented in Figure 35.1. Charts of fetal size are not specifically designed for interpretation of serial measurements and the use of specifically constructed charts of fetal growth rates or velocity can improve diagnosis. An alternative strategy is to employ charts of fetal size, which have been customized or individualized to a specific pregnancy. By calculating a ‘term optimal fetal weight’ based upon a number of easily obtained maternal and pregnancy physiological variables which have an influence upon fetal size, for example maternal weight, parity, ethnic origin, a customized ‘growth’ curve with centiles can be produced. This chart will be different for each pregnancy. A fetus with an estimated weight below the 10th centile of a customized chart is more likely to be genuinely growth restricted than a fetus which is small based on a population chart. The use of customized charts to improve the identification of growth restriction is recommended.

The fetus is growing along the 50th centile.

The fetus is growing along the 50th centile.  The fetus is SGA but does not have fetal growth restriction.

The fetus is SGA but does not have fetal growth restriction.  The fetus becomes SGA and has fetal growth restriction.

The fetus becomes SGA and has fetal growth restriction.  The fetus is growth restricted but is not SGA.

The fetus is growth restricted but is not SGA.

A detailed (anomaly) scan is warranted to look for any evidence of structural or chromosomal abnormality which makes FGR more likely than SGA (although the majority of women will already have undergone routine fetal anomaly screening at 20 weeks). Once SGA or FGR are diagnosed, it is then necessary to evaluate other parameters of fetal well-being which are considered below. In practice, most fetuses less than the 10th centile require close observation and whether they have FGR or are SGA only becomes apparent in retrospect.

Management

The main principle is to monitor the fetus and deliver at the appropriate time (Box 35.3). No antenatal therapy is of proven benefit. The options for fetal monitoring include fetal movement charts, fetal cardiotocography, biophysical scoring and Doppler blood flow studies. Of these, Doppler flow studies are the most valuable.

Fetal movement monitoring

A poorly nourished fetus will attempt to conserve energy by becoming less active and it is useful to ask the mother about the frequency of perceived fetal movements; any sudden change in the pattern of movements may be of significance and should be brought to the attention of the woman’s midwife or obstetrician. However, the utility of routine, self-documented formal fetal movement counting is not supported by scientific evaluation of its efficacy in reducing perinatal deaths.

Fetal cardiotocography

The interpretation of cardiotocographs (CTGs) is discussed on page 334. The CTG gives an indication of fetal well-being at a particular moment but has limited longer-term value. The routine use of antenatal cardiotocography is not associated with an improved perinatal outcome and antenatal CTG monitoring should be restricted to specific indications.

Biophysical profile (BPP)

This is discussed in detail on page 243 but the predictive value of adverse outcomes in cases of FGR is low. The test takes a long time to carry out, sometimes up to an hour. As most fetuses with an abnormal BPP also have abnormal umbilical artery Doppler flow, it is more appropriate to rely on Doppler studies. A BPP may be helpful in certain circumstances such as when the Doppler waveform is already abnormal, but the BPP is seldom indicated in modern-day practice.

Doppler ultrasound

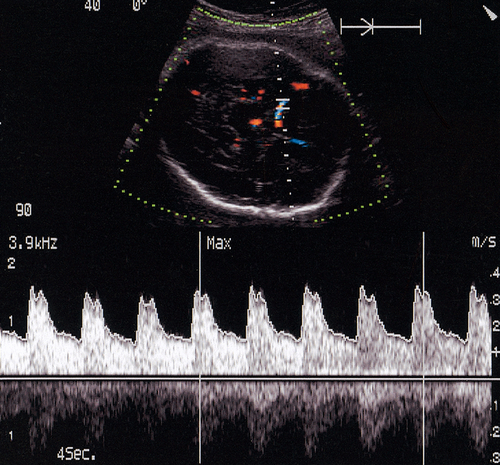

Doppler ultrasound of the umbilical artery is used as an assessment of ‘downstream’ placental vascular resistance. A normal waveform (described by semi-quantitative pulsatility or resistance indices) indicates that an SGA fetus is constitutionally small rather than growth restricted because of impaired placental function. Reduction or loss of end-diastolic flow identifies a fetus at high risk of hypoxia, and absent end-diastolic flow has been shown to be a useful discriminator between those growth-restricted fetuses at high risk of perinatal death and those at a lower risk (Fig. 35.2). Other studies have shown that the use of umbilical artery studies to monitor high-risk fetuses reduces perinatal morbidity and mortality.

Absent and reversed end-diastolic flow are associated with fetal compromise of placental origin.

Doppler studies of the fetal cerebral circulation can also provide additional useful information (Fig. 35.3). As the growth-restricted fetus redistributes its blood flow away from the less vital organs towards the brain in response to hypoxia, it is reasonable to expect an increased cerebral flow. This is indeed observed to happen, with Doppler studies showing a decreased resistance of the middle cerebral artery. As the hypoxia becomes more severe, this resistance increases again, possibly secondary to cerebral oedema. Doppler examination of the fetal venous circulation provides useful information when considering the timing of delivery. Doppler signals from the ductus venosus (a vein within the fetal liver) can be used to indirectly interpret the function of the right side of the fetal heart. Abnormal ductus venosus waveforms herald fetal demise.

In general, the sequence of changes observed with progressive fetal hypoxia is impaired growth, abnormal umbilical artery waveform, increased cerebral blood flow, abnormal ductus venosus flow followed by an abnormal fetal heart rate pattern and fetal demise. The rate of deterioration in fetal condition is unpredictable and this sequence of changes is not always present, but it does permit the development of a strategy for the outpatient management of the SGA/FGR fetus.

Overall strategy

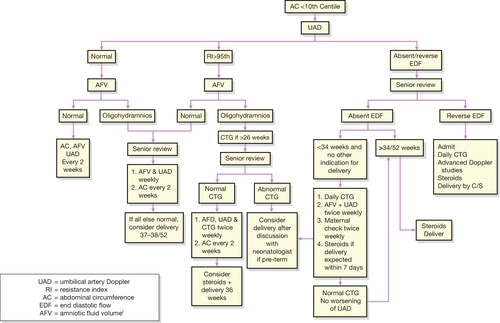

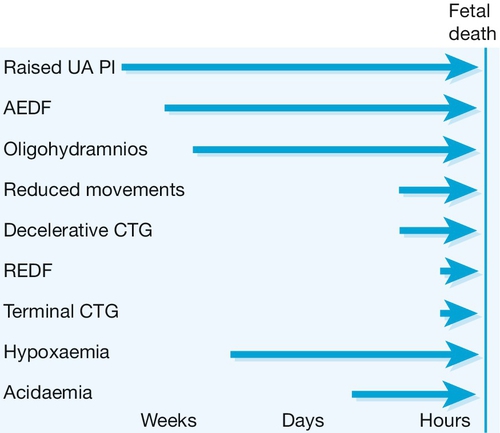

Figure 35.4 illustrates the probable sequence of events in fetal decompensation. As umbilical artery Doppler abnormalities are the first to appear, it is logical to use Doppler as the main screening tool. Thereafter, the optimal surveillance strategy in fetuses with absent or reduced end-diastolic flow involves frequent monitoring with cardiotocography, and Doppler studies of fetal vessels. The timing of the delivery will be decided by balancing the risks of keeping the baby in utero against the risks of prematurity, but delivery is appropriate when the CTG becomes abnormal (decelerations or reduced variability), there is absent end-diastolic flow in the umbilical artery with abnormal ductus venosus flow, or there is reversal of end-diastolic flow. If FGR is suspected before 34 weeks and delivery is anticipated, it is appropriate to give corticosteroids to the mother to enhance fetal lung maturation (p. 305).

Fig. 35.4The ‘decompensation cascade’ of fetal growth restriction.

Absent end-diastolic flow (AEDF) is a relatively early sign of hypoxaemia, with reduced fetal movements, cardiotocographic abnormalities and reversed end-diastolic flow (REDF) late features. UA PI, umbilical artery pulsatility index.

The mode of delivery depends on the individual circumstances, but it must be remembered that the placental reserve of some of these fetuses may be extremely low and careful monitoring in labour is required. Early recourse to caesarean section is appropriate if the monitoring shows signs of fetal compromise. Pre-labour caesarean section may be appropriate if there are significant pre-labour concerns about fetal well-being. A possible strategy for the outpatient management of women with SGA pregnancy is presented in Figure 35.5.

Long-term implications of FGR

Babies exposed to FGR are at increased risk of perinatal mortality including stillbirth (Box 35.4). Antenatal or intrapartum hypoxia may lead to long-term neurological handicap, as may more acute intrapartum hypoxia. Even if there is no overt evidence of handicap, studies of long-term development suggest that growth-restricted fetuses may be more clumsy and that their IQ may be 5–10 points lower than a normally grown sibling.

There is also evidence to suggest that FGR predisposes babies to problems much later in life, particularly non-insulin-dependent diabetes and coronary heart disease. It may be that the fetus alters its metabolism to cope with poor nutrition in utero and is subsequently less able to cope with normal carbohydrate levels in later postnatal life. It is also possible that there are vascular compensatory changes with FGR which predispose to later arterial disease.